Introduction: A Force of the Avant-Garde

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, known universally by his adopted moniker "Witkacy," stands as one of the most complex, provocative, and tragically brilliant figures of the European avant-garde. Born in Warsaw in 1885 and meeting his self-determined end in 1939 upon the Soviet invasion of Poland, Witkacy's life spanned a period of immense artistic ferment and catastrophic historical upheaval. He was a true polymath: a painter whose portraits crackle with psychological intensity, a playwright whose works anticipated the Theatre of the Absurd, a novelist delving into dystopian futures and metaphysical angst, a philosopher grappling with the "Mystery of Existence," and a pioneering photographer exploring the limits of identity. His relentless experimentation, radical theories, and uncompromising vision left an indelible mark on Polish culture and continue to fascinate and challenge audiences worldwide.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz entered the world on February 24, 1885, in Warsaw, then part of the Russian Empire. His parentage was notable: his father, Stanisław Witkiewicz Sr., was a respected painter, influential art critic, and the creator of the distinctive "Zakopane Style" in architecture. His mother, Maria Pietrzkiewicz Witkiewiczowa, came from a musical background. His godmother was the internationally renowned actress Helena Modrzejewska (Modjeska), a significant presence in his early life. Growing up primarily in the Tatra mountain resort town of Zakopane, a vibrant hub for Polish artists and intellectuals, Witkacy received an unconventional upbringing. His father, distrustful of formal schooling which he believed stifled individuality, personally oversaw his education, fostering intellectual curiosity and artistic talent.

This environment proved fertile ground for the young Witkacy's burgeoning talents. He displayed remarkable precocity, reportedly writing philosophical treatises as early as age twelve and completing his first plays by fourteen. Though he briefly attended the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts around 1905, studying under Józef Mehoffer and Jan Stanisławski, he, like his father, remained skeptical of academic institutions and did not complete his formal studies. Instead, he embarked on travels across Italy, France, and Germany, immersing himself in the latest artistic currents. During these formative years, he forged crucial friendships with figures who would profoundly shape his life and thought, notably the composer Karol Szymanowski and the future anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski.

The Australian Expedition and the Trauma of War

The year 1914 marked a significant turning point. Witkacy accompanied his close friend Bronisław Malinowski on an anthropological expedition to Australia and New Guinea (then British and German territories, respectively), serving as the expedition's draftsman and photographer. This journey into the tropics, intended as an escape and an intellectual adventure, was overshadowed by personal turmoil. News reached him of the suicide of his fiancée, Jadwiga Janczewska, a devastating blow that haunted him for years. The outbreak of World War I in August 1914 abruptly ended the expedition.

Compelled by a sense of patriotic duty and his status as a Russian subject, Witkacy traveled via Asia back to Europe to enlist in the Imperial Russian Army. He served as an officer in the Pavlovsky Regiment, a prestigious guard unit. His experiences on the brutal Eastern Front were harrowing. In July 1916, during the Brusilov Offensive, he was severely wounded at the Battle of Stokhid in Volhynia (present-day Ukraine) and endured a lengthy recovery. The war left deep psychological scars, contributing to his later pessimism and preoccupation with violence and societal collapse.

Following his convalescence, Witkacy remained in Russia, witnessing firsthand the chaos and fervor of the February and October Revolutions of 1917 in St. Petersburg (then Petrograd). While the exact nature of his involvement is debated, he was reportedly elected a political commissar by his regiment. These experiences provided raw material for his later critiques of revolution and mass movements. He managed to return to a newly independent Poland in 1918, settling back in Zakopane, profoundly changed by the cataclysmic events he had endured.

The Theory of Pure Form

Returning to Poland, Witkacy channeled his intense experiences and intellectual energy into developing his central aesthetic philosophy: the Theory of Pure Form (Czysta Forma). Articulated most fully in his essays New Forms in Painting and the Misunderstandings Arising Therefrom (1919) and Theatre: Introduction to the Theory of Pure Form in the Theatre (1923), this theory represented a radical break from realism and naturalism. Witkacy argued that the primary purpose of art was not to imitate reality or convey simple emotions, but to evoke "metaphysical feelings"—a sense of the strangeness, the mystery, and the unity of existence (Tajemnica Istnienia).

According to Witkacy, this could only be achieved by prioritizing the formal elements of art—composition, color, line, sound, movement—over representational content. The artwork should create its own autonomous reality, a tightly constructed unity of formal tensions. He believed that modern society, with its increasing mechanization, rationalization, and mass culture, was leading to the atrophy of humanity's capacity for metaphysical experience. True art, based on Pure Form, was therefore a crucial, almost spiritual, defense against this degradation, a way to reawaken the individual's sense of wonder and existential depth. This theory became the bedrock of his creative output across all disciplines.

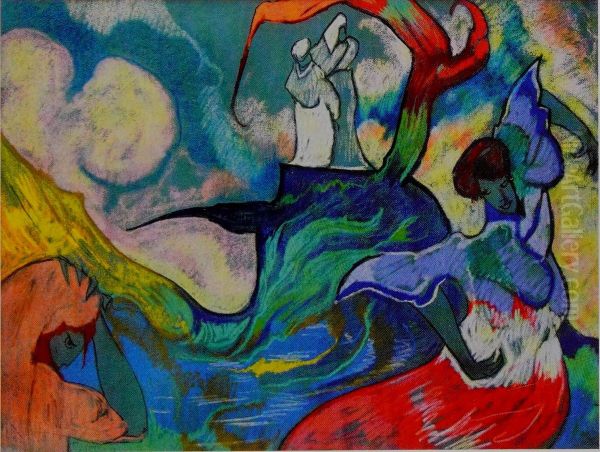

Witkacy the Painter: Portraits and Psychedelia

While he had painted before the war, Witkacy's most distinctive and prolific period as a visual artist began after his return to Poland. Facing financial pressures, he established the "S. I. Witkiewicz Portrait Painting Firm" in 1925. This was not a conventional commercial enterprise; it operated under a detailed set of humorous yet serious "Rules," which specified the conditions under which he would paint, the types of portraits offered, and even prohibited clients from criticizing the finished work. The Firm was both a source of income and a performative act, blending art, commerce, and social commentary.

Witkacy classified his portraits into types, ranging from Type A (relatively objective representations) to Type E (highly subjective, distorted compositions created under the influence of narcotics or extreme psychological states, often without the sitter present). He worked primarily in pastels on paper, a medium suited to his rapid, expressive style. His portraits are renowned for their psychological intensity. He didn't just capture likeness; he sought to excavate the inner lives of his subjects, often revealing their anxieties, neuroses, and hidden selves through exaggerated features, jarring colors, and unsettling compositions. His sitters included friends, fellow artists, intellectuals, and Zakopane society figures, such as Nena Stachurska and Helena Białynicka-Birula.

A notorious aspect of his portraiture was his documented experimentation with various psychoactive substances, including peyote, mescaline, cocaine, ether, alcohol, and copious amounts of caffeine and nicotine. He meticulously recorded the substances consumed (or abstained from) during the creation of specific works, using abbreviations like "Co." (cocaine), "Peyotl," "N.P." (nie palił – didn't smoke), or "N.Π." (nie pił – didn't drink) alongside the date and portrait type. This was not merely sensationalism; it was part of his systematic investigation into the nature of perception, consciousness, and artistic creation under altered states. His numerous self-portraits are particularly powerful examples of this relentless self-exploration.

The Playwright of the Avant-Garde

Witkacy applied his Theory of Pure Form with equal rigor to the theatre. He rejected the conventions of psychological realism that dominated the stage, aiming instead for plays that would shock, provoke, and induce metaphysical feelings through formal means. His dramas are characterized by illogical plots, grotesque and often dehumanized characters spouting philosophical tirades, sudden shifts in tone, black humor, onstage violence, and a pervasive sense of existential dread. He saw theatre not as a mirror of life, but as an artificial construct designed to assault the audience's complacency.

His plays often explore themes central to his worldview: the decline of Western civilization, the crushing of individuality by mass society, the absurdity of revolution, the search for meaning in a godless universe, and the desperate hunger for intense experience. Between 1918 and 1925, he wrote over thirty plays, though many were not performed during his lifetime. Key works include The Pragmatists (Pragmatyści, 1919), considered one of the earliest Polish avant-garde plays; Tumor Brainiowicz (Tumor Mózgowicza, 1920), a bizarre tale of a genius and his monstrous creation; The Water Hen (Kurka Wodna, 1921), a chaotic exploration of identity and art; The Madman and the Nun (Wariat i zakonnica, 1923), a claustrophobic drama set in a lunatic asylum; and his late masterpiece, The Shoemakers (Szewcy, written 1931-34), a savage satire depicting the cyclical and ultimately futile nature of revolution. Witkacy's dramatic innovations anticipated many elements of the later Theatre of the Absurd associated with writers like Eugène Ionesco and Samuel Beckett.

Novels of Metaphysical Hunger

Witkacy's restless creativity also found expression in the novel form. His two major novels, Farewell to Autumn (Pożegnanie jesieni, 1927) and Insatiability (Nienasycenie, 1930), are sprawling, challenging works that translate his philosophical preoccupations and aesthetic principles into prose. Like his plays, they eschew conventional narrative structures and psychological realism in favor of grotesque characters, philosophical digressions, bizarre events, and an atmosphere of impending doom. They explore the desperate search for meaning and intense experience—metaphysical, sexual, artistic, narcotic—in a world perceived as spiritually bankrupt and heading towards catastrophe.

Farewell to Autumn follows the decadent exploits of a group of artists and intellectuals against the backdrop of an impending Bolshevik-style revolution, exploring themes of disillusionment, artistic impotence, and the destructive nature of love. Insatiability is arguably his magnum opus in prose, a vast dystopian novel depicting a future Poland succumbing to a mysterious Sino-Mongolian invasion that pacifies the population with a happiness drug ("Murti-Bing pills"). The novel is a terrifyingly prophetic vision of totalitarianism, the manipulation of consciousness, the loss of individuality, and the "insatiability" of the human desire for meaning in the face of overwhelming societal decay. Both novels are saturated with Witkacy's characteristic black humor, philosophical depth, and linguistic inventiveness.

Philosophical Explorations

Underpinning all of Witkacy's artistic endeavors was a serious and sustained engagement with philosophy. While not a systematic academic philosopher, he developed a unique ontological system, sometimes described as biological monadology, heavily influenced by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz but infused with his own pessimistic and modern sensibility. Central to his thought was the concept of the "Mystery of Existence"—the fundamental inexplicability and wonder of being itself. He believed that individual beings ("Particular Existences") possessed a dual nature, simultaneously experiencing unity and plurality.

Witkacy lamented what he saw as the progressive decline of humanity's ability to perceive this Mystery, attributing it to social leveling, technological advancement, and the rise of materialistic philosophies. His philosophical writings, including his major work Concepts and Principles Implied by the Concept of Existence (Pojęcia i twierdzenia implikowane przez pojęcie Istnienia, 1935), aimed to reassert the importance of metaphysics and defend the uniqueness of individual consciousness. His thought bears the imprint of various influences, including Arthur Schopenhauer, Friedrich Nietzsche (whose ideas he both admired and critically engaged with), and potentially the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl and the characterology of Ernst Kretschmer. Philosophy, for Witkacy, was not separate from his art but inextricably linked to it, providing the intellectual framework for his aesthetic experiments.

Photography: Faces and Masks

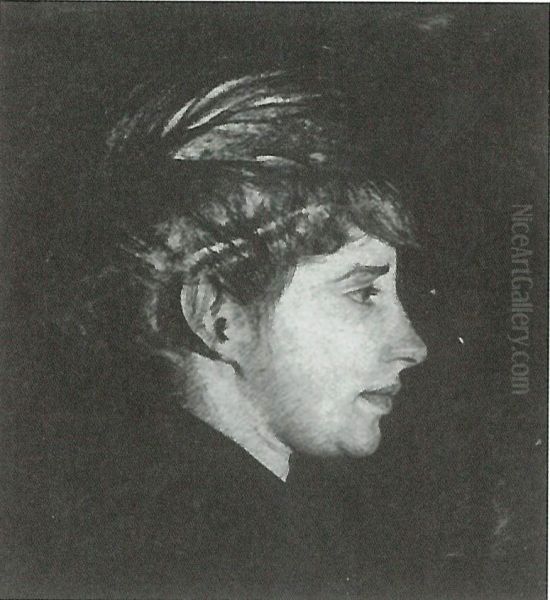

Witkacy was also a remarkably innovative photographer, utilizing the medium long before it gained widespread acceptance as an art form. Beginning with his work for Malinowski and continuing throughout the 1920s and 30s, he approached photography with the same experimental spirit he brought to painting and theatre. He was particularly interested in portraiture and self-portraiture, using the camera to explore identity, psychological states, and the performative nature of the self.

His photographic work often features extreme close-ups, unconventional framing, dramatic lighting, and deliberate distortions. He frequently photographed his friends and himself making faces, pulling expressions, or adopting various personas, pushing the boundaries of conventional portraiture. His series of "Multiple Self-Portraits," created using mirrors or multiple exposures, are striking investigations into the fragmented modern psyche. Like his paintings, his photographs often possess a raw, unsettling quality, capturing moments of vulnerability, absurdity, or intense emotion. Witkacy's photographic experiments place him among the pioneers of subjective and avant-garde photography in Europe.

Contemporaries and the Zakopane Milieu

Witkacy did not create in a vacuum. He was deeply embedded in the vibrant cultural life of interwar Poland, particularly in Zakopane. His father's legacy and the pervasive influence of the Zakopane Style formed the backdrop to his youth. He maintained lifelong, albeit sometimes turbulent, friendships with key figures like the composer Karol Szymanowski and the anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski. His intellectual sparring partner and rival theorist was Leon Chwistek, another polymath (painter, mathematician, philosopher) who developed his own theory of Formism.

Witkacy was associated with the Polish Formists (Formiści), an influential avant-garde group active roughly between 1917 and 1922, which included artists like Tytus Czyżewski, Zbigniew Pronaszko, and Andrzej Pronaszko. While sharing their emphasis on form over representation, Witkacy maintained his distinct theoretical stance. He also had complex relationships with the other two giants of Polish modernist literature, Bruno Schulz and Witold Gombrowicz. They shared mutual respect and engaged in intellectual dialogue, but also maintained a critical distance, representing different facets of the Polish avant-garde. Other notable figures in his circle included the poet and playwright Tadeusz Miciński, the sculptor August Zamoyski, the painter Rafał Malczewski (son of the Symbolist painter Jacek Malczewski), the dynamic painter Zofia Stryjeńska, and poets associated with the Krakow Avant-Garde like Tadeusz Peiper and Aleksander Wat. Even the Nobel laureate Henryk Sienkiewicz, though of an older generation, was a family friend who supported Polish independence efforts.

Final Years and Tragic End

The 1930s were a period of increasing darkness for Witkacy, both personally and politically. While he continued to work relentlessly across multiple disciplines, he felt increasingly isolated and misunderstood. His dire predictions about the future of European civilization seemed to be materializing with the rise of Nazism in Germany and Stalinism in the Soviet Union. He suffered from periods of depression and financial hardship, though the Portrait Firm provided some income. His philosophical pessimism deepened, and his later works, like the play The Shoemakers, reflect a profound sense of disillusionment.

The outbreak of World War II with the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, confirmed his worst fears. Unwilling to live under foreign occupation, especially Nazi rule, Witkacy fled Warsaw eastward with his companion Czesława Oknińska-Korzeniowska. They reached the remote village of Jeziory in Polesie (now Velyki Ozera, Ukraine). On September 17, news arrived that the Soviet Union had invaded Poland from the east, sealing the country's fate. For Witkacy, who had witnessed the Bolshevik revolution and deeply distrusted communism, this was the final blow. On September 18, 1939, Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz and Czesława Oknińska entered into a suicide pact. He ingested a lethal dose of Veronal and slit his wrists. He died; Oknińska survived. He was 54 years old.

Legacy and Rediscovery

For nearly two decades after his death, Witkacy's work remained largely obscure, suppressed or ignored during the German occupation and the subsequent Stalinist period in Poland, where his formalism and perceived decadence were ideologically unacceptable. However, beginning in the late 1950s, coinciding with the post-Stalinist "thaw," his work began to be rediscovered and reassessed. His plays, in particular, struck a chord with a new generation, and he was hailed as a major precursor to the Theatre of the Absurd and existentialist thought.

Figures like Tadeusz Kantor and Jerzy Grotowski acknowledged his influence on Polish experimental theatre. His novels gained recognition for their prophetic vision and stylistic innovation. His paintings and photographs were exhibited more widely, revealing the full scope of his visual genius. Today, Witkacy is firmly established as one of the indispensable figures of Polish modernism, standing alongside Bruno Schulz and Witold Gombrowicz as part of a trinity of groundbreaking interwar writers and artists. His multifaceted output, his radical theories, his exploration of the extremes of human experience, and his tragic life continue to inspire artists, writers, scholars, and audiences both in Poland and internationally, cementing his status as a unique and enduring force in 20th-century culture.