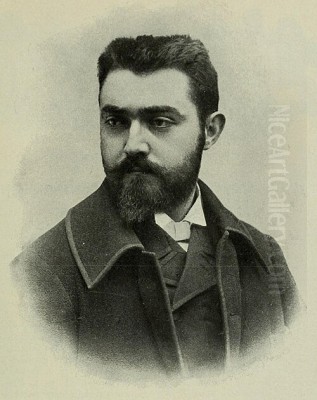

Adrien Henri Tanoux stands as a notable, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant art world of late 19th and early 20th century France. A painter whose work navigated the currents of Romantic Realism, Academic tradition, and the burgeoning allure of Orientalism, Tanoux carved out a distinct niche for himself. His canvases, often depicting sensuous nudes, intimate genre scenes, and evocative Orientalist subjects, reflect both the artistic conventions of his time and a personal vision that continues to attract interest.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Marseille and Paris

Born on October 18, 1865, in the bustling port city of Marseille, Adrien Henri Tanoux (often cited with his given names reversed as Henri Adrien Tanoux, though Adrien Henri is generally considered more accurate) was immersed in a culturally rich environment from a young age. Marseille, with its Mediterranean light and diverse population, likely provided early visual stimuli for the budding artist. His formal artistic education commenced in his hometown, where, in 1878, he enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts de Marseille (Marseille School of Art and Design). This institution would have provided him with a foundational grounding in drawing, perspective, and the classical principles that underpinned much of French art education at the time.

After honing his initial skills in Marseille, Tanoux, like many ambitious young artists of his generation, set his sights on Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world. In 1886, he gained admission to the prestigious École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. This was a significant step, placing him at the heart of academic artistic training in France. At the École, he had the distinct privilege of studying under Léon Bonnat (1833-1922), a highly respected and influential figure in the French art establishment. Bonnat, known for his powerful portraits and religious paintings, was a staunch advocate of rigorous draughtsmanship and a somewhat conservative, yet robust, realist style. His tutelage would have emphasized anatomical accuracy, careful composition, and a mastery of traditional painting techniques, all of which are evident in Tanoux's subsequent work. Some accounts also suggest earlier, broader studies, including French language and painting at a "Guolangbo School" on the outskirts of Paris, followed by specialized art history training, indicating a comprehensive approach to his artistic development.

Navigating the Parisian Art World: The Salon and Beyond

The late 19th century Parisian art scene was a dynamic and competitive arena. The official Salon, organized by the Société des Artistes Français, remained the primary venue for artists to exhibit their work, gain recognition, and attract patrons. Tanoux actively participated in this system, regularly submitting his paintings to the Salon. His consistent presence and the quality of his work led to him becoming a member of the Société des Artistes Français, a mark of peer recognition. He is documented as having received accolades at the Salon, underscoring his acceptance within the established art community.

While the Salon system was dominated by Academic art, championed by figures like William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905) and Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), it was also a period of immense artistic innovation. Impressionism, with pioneers like Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), had already challenged academic conventions, and Post-Impressionist movements were further expanding the boundaries of art. Tanoux, while clearly rooted in academic training, was not immune to these broader currents. His work often displays a sensitivity to light and atmosphere that suggests an awareness of Impressionist techniques, even if his core style remained anchored in realism. He was a contemporary of artists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901), who captured the vibrant nightlife of Paris, and Henri Fantin-Latour (1836-1904), known for his refined portraits and still lifes, though Tanoux's thematic concerns often diverged.

Artistic Style: Romantic Realism and Orientalist Visions

Tanoux's artistic output is most accurately characterized as Romantic Realism. His commitment to realistic depiction, inherited from his academic training under Bonnat, is evident in the careful rendering of figures, textures, and settings. However, his subjects and their treatment often carry an emotional charge, a sense of drama, or an exotic allure that aligns with Romantic sensibilities. This blend allowed him to create works that were both technically accomplished and engaging on an emotional or narrative level.

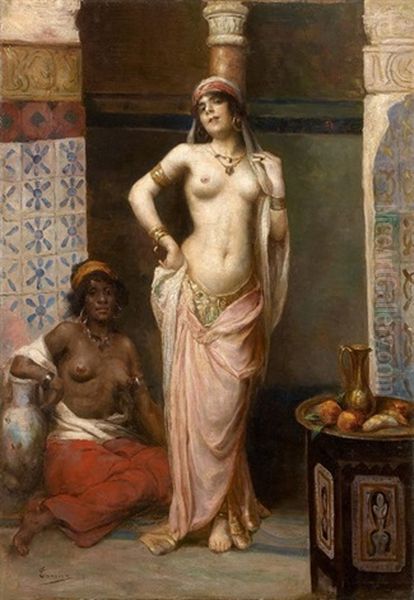

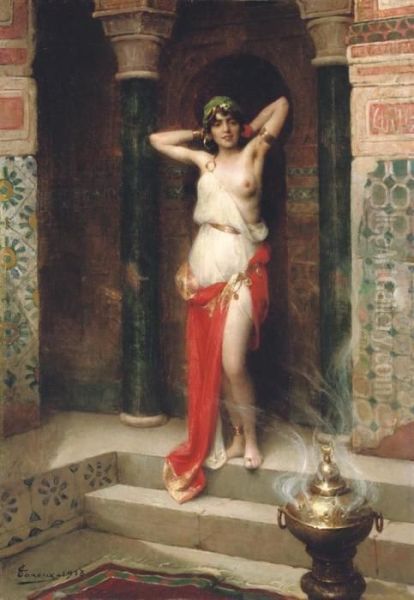

A significant portion of Tanoux's oeuvre is dedicated to Orientalism. The fascination with the "Orient"—a term then encompassing North Africa, the Middle East, and sometimes further afield—had been a powerful force in European art since the early 19th century, with artists like Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) and later Jean-Léon Gérôme and Eugène Fromentin (1820-1876) popularizing its themes. Tanoux continued this tradition, producing numerous paintings depicting harem scenes, odalisques, and other subjects drawn from an imagined East. These works, such as La favorite du sultan and the frequently auctioned Odalisque, catered to a European taste for the exotic, the sensual, and the picturesque. While modern perspectives often critique Orientalism for its colonial gaze and stereotypical representations, these paintings were highly popular in their time and demonstrate Tanoux's skill in creating lush, atmospheric compositions. His depictions often focused on the female form within these exotic settings, blending the allure of the nude with the mystique of the Orient.

Key Themes and Subjects in Tanoux's Work

Beyond his prominent Orientalist pieces, Tanoux explored several other themes that reveal the breadth of his artistic interests and skills. His ability to capture the nuances of human interaction and environment made him a versatile painter.

Genre Scenes and Parisian Life

Tanoux produced genre scenes that offer glimpses into contemporary life, though perhaps less gritty than some of his realist predecessors or contemporaries. Works like Café Interior (or Coffee Shop Interior) and Street Theatre suggest an interest in capturing the social fabric of his time. These paintings would have allowed him to explore character, atmosphere, and narrative within everyday settings. His painting The Garden Lunch, for example, likely depicted a leisurely moment, a popular theme that allowed for the portrayal of figures in natural light and relaxed poses, somewhat akin to the social scenes captured by Impressionists, though rendered with a more academic finish. The painting The Next Commission, mentioned in auction records, hints at a narrative, possibly set within an artist's studio or a patron's home, offering a commentary on the art world itself or a dramatic social interaction.

The Female Nude: A Persistent Motif

The female nude was a central and recurring theme in Tanoux's art, as it was for many academic painters of his era, including Alexandre Cabanel (1823-1889) and Paul Baudry (1828-1886). Tanoux approached the nude with a sensuous realism, often placing his figures in mythological, allegorical, or Orientalist contexts. His nudes are characterized by their smooth, idealized flesh tones and graceful poses, adhering to academic conventions of beauty while often imbuing them with a palpable sensuality. Works like Salambo, likely inspired by Gustave Flaubert's novel, would have combined historical or literary themes with the depiction of the female form. He was compared by some to Georges Rochegrosse (1859-1938), another artist known for his dramatic historical scenes and depictions of nudes, though Rochegrosse often leaned more towards Symbolist or overtly dramatic historical narratives. Tanoux's nudes, while sometimes provocative, generally remained within the bounds of academic acceptability, focusing on aesthetic beauty and skilled anatomical rendering. A piece titled Young Woman in Gypsy Clothes in a Field also points to his interest in portraying women in various evocative, sometimes romanticized, cultural guises.

Portraits and Other Subjects

While less emphasized in summaries of his work, it is probable that Tanoux, like most academically trained artists, also undertook portrait commissions. His training under Bonnat, a master portraitist, would have equipped him well for this genre. Furthermore, his general skill in figure painting suggests an aptitude for capturing likeness and character. His broader repertoire might have also included landscapes or cityscapes beyond the specific Street Scene in Algiers, reflecting the diverse interests of a working artist in a competitive market. His style, a blend of academic precision with a touch of romantic atmosphere, would have lent itself well to various subjects demanded by patrons and the Salon.

Notable Works and Their Characteristics

Several specific works by Tanoux are frequently cited and help to illustrate his artistic concerns and stylistic approach. These paintings showcase his technical skill, his thematic preferences, and his engagement with the artistic trends of his time.

Odalisque: This is perhaps one of his most emblematic and frequently auctioned works. The title itself places it firmly within the Orientalist tradition. Such paintings typically depict a reclining female slave or concubine in a harem setting, often nude or semi-nude, surrounded by luxurious fabrics, intricate patterns, and exotic objects. Tanoux's Odalisque would have emphasized sensuality, exoticism, and meticulous rendering of textures, appealing to the contemporary taste for such subjects. The high auction price achieved by an Odalisque at Christie's in 2012 ($76,635) attests to the enduring market appeal of his Orientalist nudes.

Street Scene in Algiers: This title indicates a direct engagement with North African subject matter, a common destination for Orientalist painters. Unlike the interior, often fantasized, harem scenes, a street scene would have offered Tanoux the opportunity to depict the daily life, architecture, and vibrant atmosphere of Algiers. Such works often focused on bustling markets, quiet alleyways, or local inhabitants in traditional attire, providing a sense of authenticity and local color. This piece would showcase his skills in capturing light, architectural detail, and human activity within a specific cultural context.

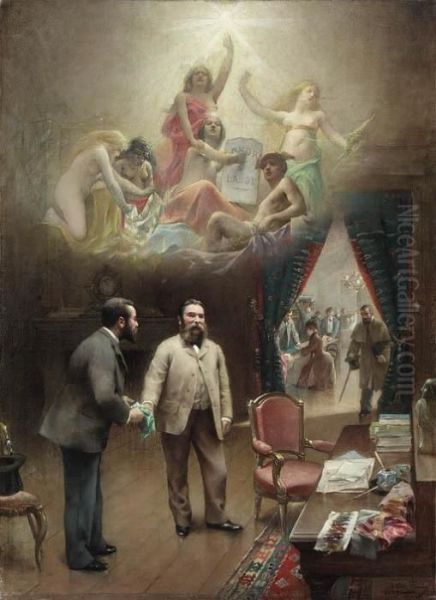

The Next Commission: This intriguing title suggests a narrative painting, possibly set in an artist's studio or a patron's opulent interior. It could depict an artist interacting with a client, or perhaps a more allegorical scene related to artistic inspiration or patronage. The mention of "nude angels and goddesses" within some descriptions of this work suggests a blend of realism with mythological or allegorical elements, a common practice in academic art. Such a painting would highlight Tanoux's ability to handle complex compositions and convey narrative through gesture and expression.

Salambo: Inspired by Flaubert's historical novel set in ancient Carthage, this subject was popular among artists for its dramatic potential and exotic setting. A painting of Salambo would likely feature the eponymous priestess in a scene of high emotion or ritual, often involving a degree of nudity or elaborate costume, allowing Tanoux to combine historical narrative with his skill in depicting the female form and rich textures.

La favorite du sultan (The Sultan's Favorite): Similar to Odalisque, this title evokes the intimate and often eroticized world of the Ottoman harem as imagined by European artists. It would likely feature a beautifully rendered female figure, singled out for the Sultan's attention, adorned with jewels and fine garments, within a lavishly decorated interior. Such works played into fantasies of power, sensuality, and exotic luxury.

These works, alongside others like Café Interior, Street Theatre, and The Garden Lunch, demonstrate Tanoux's versatility in subject matter while consistently showcasing his polished technique and his ability to create evocative and often sensuous imagery. His style, while rooted in the academic tradition of artists like his teacher Léon Bonnat or the celebrated Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867) from an earlier generation of classicists, also incorporated a romantic sensibility and an awareness of contemporary tastes for realism and exoticism.

Later Career, Legacy, and Controversies

Adrien Henri Tanoux continued to paint and exhibit throughout his career, passing away in 1923. His work remained largely within the Romantic Realist and Orientalist veins that he had established. While he may not have achieved the revolutionary fame of Impressionist or Post-Impressionist masters like Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) or Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), he was a respected and successful artist within his own sphere. His paintings found buyers, and his regular presence at the Salon ensured his visibility.

The legacy of artists like Tanoux is complex. In the mid-20th century, academic and Orientalist art fell out of favor with many critics and art historians who championed modernism. However, there has been a more recent scholarly and market reassessment of 19th-century academic art, appreciating its technical skill and historical context. Tanoux's works continue to appear at auction, often commanding respectable prices, particularly his Orientalist nudes.

Controversies surrounding his work are typical of those associated with Orientalism and the depiction of the female nude in his era. The Orientalist paintings, while aesthetically pleasing to many at the time, are now often viewed through a post-colonial lens, critiqued for perpetuating stereotypes and a Western male gaze upon Eastern cultures. Similarly, the sensuousness of his nudes, while appealing to patrons, could sometimes border on what was considered provocative, though generally remaining within the accepted conventions of the Salon.

An interesting, albeit indirect, anecdote concerns the collection of his work. It is noted that some of Tanoux's paintings were acquired by Sun Peicang, a significant Chinese collector active in the early 20th century who played a role in introducing Western art to China. The fact that Tanoux's work found its way into such a collection speaks to its international appeal, though the subsequent mystery surrounding the whereabouts of much of Sun Peicang's collection adds another layer to the story of Tanoux's paintings.

Conclusion: An Enduring Appeal

Adrien Henri Tanoux was an artist of his time, skillfully navigating the demands of the French academic system while infusing his work with a personal blend of realism, romanticism, and exoticism. His education under Léon Bonnat provided him with a strong technical foundation, which he applied to a range of subjects, from intimate genre scenes to lavish Orientalist fantasies and sensuous nudes. While he operated within a more traditional framework compared to the avant-garde movements of his day, his paintings possess a distinct charm and technical polish that continue to attract collectors and art enthusiasts.

His contributions to Orientalist art, his skilled depictions of the female form, and his ability to capture atmosphere and narrative place him as a competent and engaging painter of the Belle Époque. Though perhaps not a household name like some of his more revolutionary contemporaries such as Edgar Degas (1834-1917) or later modernists like Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Tanoux's work provides valuable insight into the artistic tastes and cultural currents of his era, and his paintings maintain an aesthetic appeal that transcends their historical context, ensuring his place within the broader narrative of late 19th and early 20th-century European art. His art serves as a reminder of the diverse artistic expressions that flourished during this vibrant period in art history.