Introduction to the Artist

Émile Eisman-Semenowsky stands as a fascinating figure within the vibrant tapestry of late 19th and early 20th-century Parisian art. Born in 1857, likely within the borders of modern-day Poland which was then part of the Russian Empire, Eisman-Semenowsky carved a distinct niche for himself in the bustling art capital of the world. Of Polish-Jewish heritage, he navigated the complex cultural currents of his time, eventually becoming recognized as a French painter, deeply integrated into the artistic life of Paris where he lived and worked for many years until his death in 1911.

His artistic reputation rests primarily on his captivating portraits of women, particularly those belonging to the upper echelons of society. These works are characterized by a delicate sensibility, a refined technique, and a distinct blend of contemporary European elegance with the allure of the exotic, drawing heavily from the popular Orientalist and Medievalist trends of the era. He became a notable presence in the Parisian art scene from the 1880s onwards, his work resonating with the tastes of the bourgeoisie and aristocracy alike.

Origins and Artistic Formation

Details surrounding Émile Eisman-Semenowsky's early life and formal artistic training remain somewhat scarce. It is known that he hailed from a Polish-Jewish background, born into a region under Russian imperial control. Unlike some of his Polish contemporaries who might have sought training at established institutions in Warsaw or Krakow, available records suggest Eisman-Semenowsky did not pursue his artistic education at these specific universities. The precise path that led him from Poland to Paris, the epicenter of the art world, is not fully documented.

However, his arrival and establishment in Paris by the 1880s mark the beginning of his documented professional career. Paris, during this period often referred to as the Belle Époque, was a magnet for artists from across Europe and beyond. It offered unparalleled opportunities for training, exhibition, patronage, and immersion in avant-garde ideas, although Eisman-Semenowsky would largely align himself with more commercially popular styles rather than radical movements like Impressionism or Post-Impressionism, which were concurrently challenging artistic conventions. His focus would soon center on portraiture that appealed to the aesthetic preferences of Parisian high society.

Artistic Style: Delicacy, Color, and Influence

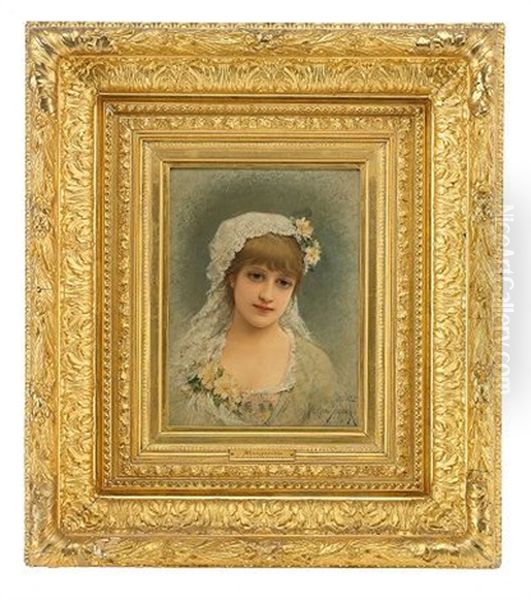

The hallmark of Eisman-Semenowsky's style is its refined execution and gentle charm. He employed delicate brushwork, creating smooth surfaces and subtle gradations of tone that lent an air of softness and sophistication to his subjects. His color palette was often characterized by harmonious and pleasing combinations, avoiding harsh contrasts in favor of a more muted, elegant aesthetic. This technical approach was perfectly suited to his primary subject matter: the idealized depiction of feminine beauty and grace.

His work shows clear influences from prevailing artistic trends. Orientalism, the European fascination with the cultures of North Africa and the Middle East (often romanticized and filtered through a Western lens), is frequently evident. This manifested in the inclusion of exotic costumes, intricate jewelry, suggestive props, or atmospheric settings that hinted at distant lands. Simultaneously, a subtle echo of Medievalism, a romantic longing for the aesthetics and perceived chivalry of the Middle Ages, can sometimes be discerned, perhaps in the poise of his figures or the richness of certain details. He skillfully blended these influences with the contemporary fashions and sensibilities of Parisian society.

The Parisian Woman as Muse

Émile Eisman-Semenowsky dedicated much of his artistic output to the portrayal of women, particularly the elegant Parisienne who populated the salons and social circles of the capital. His portraits often depict women from the upper-middle class or aristocracy, presenting them with an air of poise, refinement, and sometimes a touch of alluring mystery. He possessed a keen ability, noted by observers, to capture not just a likeness, but also the subtle nuances of expression, gesture, and what was perceived as feminine intuition.

His subjects are typically shown in fashionable attire, sometimes embellished with the aforementioned Orientalist elements like elaborate headdresses or rich fabrics. Their gazes are often direct yet gentle, their expressions ranging from contemplative serenity to a soft, engaging smile. These were not typically portraits aiming for stark psychological realism in the vein of an Edgar Degas; rather, they were idealized representations designed to flatter the sitter and appeal to the viewer's appreciation for beauty, elegance, and social grace. His success in this genre underscores the demand for such images among the affluent patrons of the era.

The Significance of Flowers

A recurring and notable motif in Eisman-Semenowsky's oeuvre is the prominent inclusion of flowers, especially roses. Flowers were not mere decorative afterthoughts in his compositions; they often played a significant role in enhancing the overall aesthetic and symbolic meaning of the work. Roses, in particular, with their long-established associations with love, beauty, and femininity, complemented his depictions of elegant women perfectly.

In paintings like Aux Roses (Elegance Among Roses) and A Classical Beauty with Roses, the floral elements are integral to the composition, framing the subject, adding bursts of color, and reinforcing the themes of natural beauty and cultivated refinement. The delicate rendering of the petals often mirrored the soft textures of the sitter's skin or attire. This use of flowers connected his work to a broader tradition in portraiture and genre painting where floral symbolism was employed to enrich the narrative or enhance the sitter's attributes, adding a layer of cultural value recognized by his audience.

Notable Works

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné might be complex to assemble, several works stand out as representative of Eisman-Semenowsky's style and subject matter. His painting titled Aux Roses exemplifies his skill in combining portraiture with floral elements, likely depicting an elegant woman surrounded by or holding roses, showcasing his characteristic soft brushwork and pleasing composition.

Another significant work often cited is A Classical Beauty with Roses. The title suggests a blend of contemporary elegance with perhaps a nod to classical ideals of beauty, again emphasizing the importance of roses within the composition. This title hints at the artist's ability to evoke timeless notions of beauty while grounding his subject in the fashionable context of his time.

The painting Marguerite is also mentioned as a well-regarded piece. While the specific details of this work are not provided in the initial summary, the name itself evokes literary and operatic heroines, suggesting a potentially romantic or narrative element, possibly depicting a figure embodying innocence or tragic beauty, themes popular in the 19th century. These works collectively highlight his focus on feminine beauty, often intertwined with floral motifs and executed with a refined, appealing technique.

Eisman-Semenowsky and His Contemporaries

Émile Eisman-Semenowsky's career unfolded during a period of immense artistic activity and diversity in Paris. While not aligned with the revolutionary avant-garde movements, he operated within a thriving ecosystem of academic and Salon painters, portraitists, and genre specialists. A specific connection noted is his role as an assistant to the Belgian painter Jan van Beers (1852–1927). Van Beers was known for his own highly finished portraits and genre scenes, often depicting fashionable women, and was himself a commercially successful, if sometimes controversial, figure in Paris. Eisman-Semenowsky even served as a witness for van Beers in a case involving accusations of plagiarism, indicating a close working relationship at one point.

Placing Eisman-Semenowsky in the broader context, he worked concurrently with renowned portraitists who captured the elite of the era, such as the Italian expatriate Giovanni Boldini (1842–1931), known for his flamboyant and dynamic style, and the French master Carolus-Duran (1837–1917), who was also a celebrated teacher (notably of John Singer Sargent). While perhaps not reaching their level of fame, Eisman-Semenowsky catered to a similar clientele seeking elegant representations. His work can also be seen alongside that of James Tissot (1836–1902), who excelled in depicting the fashionable life of Paris and London.

The Allure of Orientalism in Late 19th Century Paris

Eisman-Semenowsky's engagement with Orientalism places him firmly within a major artistic current of the 19th century. This fascination with the East was fueled by colonial expansion, increased travel (real or imagined), world fairs, and a romantic desire for the exotic and picturesque as an antidote to modern industrial life. Paris was a major center for Orientalist painting. Artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904) were giants in the field, creating highly detailed, often dramatic scenes of North African and Middle Eastern life that profoundly influenced public perception.

Other prominent Orientalists active during Eisman-Semenowsky's time included Ludwig Deutsch (1855–1935) and Rudolf Ernst (1854–1932), both Austrian painters working in Paris known for their meticulous renderings of Islamic architecture, scholars, and guards. The American Frederick Arthur Bridgman (1847–1928) also found great success in Paris with his luminous depictions of Algerian scenes. Eisman-Semenowsky's Orientalism appears to have been less focused on ethnographic detail or grand historical narratives and more on incorporating exotic elements – costumes, jewelry, textiles – into his portraits of European women, adding a layer of fashionable fantasy and allure that appealed directly to his market.

Navigating the Salon System and the Art Market

To achieve the recognition and patronage Eisman-Semenowsky enjoyed, participation in the official Paris Salon was crucial for much of the 19th century. While direct records of his Salon submissions require specific research, his style – polished, agreeable, and technically proficient – was well-suited to the tastes of the Salon juries and the public who frequented these massive annual exhibitions. Success at the Salon could lead to critical notice, state purchases, and, importantly, commissions from wealthy clients.

His work found particular favor not only among the Parisian elite but also with American collectors. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a surge in American wealth and a corresponding appetite for European art, particularly works that conveyed sophistication, beauty, and a connection to European cultural traditions. Eisman-Semenowsky's charming portraits fit this demand perfectly. His ability to cater to the tastes of the bourgeoisie, producing works that were both aesthetically pleasing and socially aspirational, was key to his professional success. He operated skillfully within the established art market of his time, producing work that was both admired and commercially viable.

Contrasting Styles: Beyond the Academy

While Eisman-Semenowsky thrived by creating works aligned with popular and academic tastes, it's important to remember the radical artistic developments occurring simultaneously in Paris. The Impressionists, like Claude Monet (1840–1926) and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), had already revolutionized painting with their focus on light, color, and capturing fleeting moments of modern life, often working outdoors. Renoir, too, painted beautiful women, but with a distinctly different technique and sensibility, emphasizing vibrant color and looser brushwork.

Following them, Post-Impressionists like Georges Seurat (1859–1891) experimented with scientific color theories, while Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) and Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) pushed towards expressive color and form, often leaving Paris for more remote locales. Even within Poland, contemporaries like Olga Boznańska (1865–1940), who also worked in Paris, developed a more psychologically intense and modern style of portraiture. Mentioning these figures helps contextualize Eisman-Semenowsky's artistic choices: he deliberately pursued a path of refined elegance and popular appeal rather than engaging with the avant-garde experimentation defining modernism. His contemporaries also included major figures from Eastern Europe whose paths sometimes crossed in Paris, such as the great Russian realist Ilya Repin (1844-1930) or the Polish academic master Henryk Siemiradzki (1843-1902), though direct collaboration with Eisman-Semenowsky isn't documented.

Legacy and Reception

Émile Eisman-Semenowsky was undoubtedly a successful artist in his own time. His portraits were sought after, admired for their beauty and technical skill, and collected by prominent members of society on both sides of the Atlantic. He fulfilled a specific desire within the art market for images that conveyed elegance, charm, and a touch of fashionable exoticism. His contribution lies in his consistent production of high-quality portraits within this specific genre, capturing a particular facet of Belle Époque society.

However, like many artists who adhered closely to the academic or popular tastes of their day, his fame has perhaps been overshadowed in art historical narratives by the more revolutionary figures who broke with tradition. He is not typically counted among the innovators who reshaped the course of Western art. Yet, his work remains a testament to the skill and aesthetic preferences prevalent in late 19th-century Paris. His paintings continue to appear on the art market, appreciated by collectors for their decorative qualities, historical context, and the gentle, idealized vision of femininity they represent. He remains a significant example of a successful Salon-oriented painter navigating the rich artistic landscape of his era.

Conclusion

Émile Eisman-Semenowsky represents a skillful and successful exponent of late 19th-century Parisian portraiture. Emerging from a Polish-Jewish background, he established himself in the French capital, creating a body of work celebrated for its delicate execution, harmonious colors, and appealing subject matter. His depictions of elegant women, often adorned with flowers or subtle Orientalist details, captured the aesthetic ideals and aspirations of the Belle Époque bourgeoisie and aristocracy. While working alongside and sometimes collaborating with figures like Jan van Beers, and concurrently with major academic painters like William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905) and Orientalists like Gérôme, he carved his own niche. Though perhaps less known today than the pioneering modernists, Eisman-Semenowsky's art provides valuable insight into the popular tastes and cultural currents of his time, leaving behind a legacy of charming images that continue to evoke the elegance of a bygone era.