Henri Charles Manguin stands as a significant figure in the vibrant tapestry of early 20th-century French art. Born in Paris on March 23, 1874, and passing away in Saint-Tropez on September 25, 1949, Manguin's life spanned a period of radical artistic transformation. He is primarily celebrated as one of the core members of the Fauvist movement, a group renowned for its revolutionary use of intense, non-naturalistic color and bold brushwork. Manguin, often dubbed the "voluptuous painter" or the "painter of happiness," carved a unique niche within Fauvism, characterized by his luminous palette, fluid lines, and an enduring sense of joie de vivre that permeated his canvases. His work, deeply rooted in the observation of nature yet liberated by subjective emotion, offers a compelling window into the artistic ferment of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Paris

Henri Manguin's journey into the world of art began in Paris, the undisputed center of the art world at the time. His childhood was marked by the early loss of his father when Henri was just six years old, leaving his mother to raise him. This early experience may have contributed to the sense of warmth and domestic intimacy often found in his later works. In 1890, at the age of sixteen, Manguin made the decisive choice to abandon his conventional studies and dedicate himself entirely to painting, a testament to his early passion and determination.

His formal artistic education commenced in 1894 when he gained admission to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. This institution, while traditional, provided a crucial foundation. More importantly, it placed him under the tutelage of the Symbolist painter Gustave Moreau. Moreau's studio was a crucible of talent and burgeoning modernism. It was here that Manguin formed formative and lifelong friendships with fellow students who would soon become pillars of modern art, most notably Henri Matisse and Charles Camoin. Albert Marquet was another close associate from this period, forming a quartet of friends who shared artistic aspirations and critiques.

During these formative years, Manguin, alongside Matisse, Camoin, and Marquet, spent considerable time at the Louvre Museum. They diligently copied the works of Renaissance masters, absorbing lessons in composition, form, and technique. This practice, seemingly traditional, was crucial. It provided them with a deep understanding of art history and technical skill, which they would later subvert and transform in their own revolutionary styles. For Manguin, this early exposure to classical harmony likely influenced his later ability to balance vibrant color with coherent composition.

The Influence of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism

While Manguin's destiny lay with Fauvism, his artistic development was significantly shaped by the preceding generation of innovators. The influence of Impressionism is readily apparent in his work, particularly in his handling of light and color. He admired the way Impressionist masters like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir captured fleeting moments and the effects of natural light using broken brushwork and a bright palette. Manguin adopted their love for painting outdoors (en plein air) and their focus on contemporary life and landscape, though he would push their coloristic discoveries further.

His use of bright, often pastel-like, luminous colors owes a debt to the Impressionist sensibility. However, Manguin did not merely replicate Impressionist techniques. He synthesized their approach with the structural concerns and expressive color theories emerging from Post-Impressionism. The work of Paul Cézanne, with its emphasis on underlying geometric forms and constructive brushstrokes, provided a model for building solid compositions even amidst vibrant color.

Furthermore, the emotional intensity and subjective use of color pioneered by Vincent van Gogh resonated deeply with the emerging Fauvist generation, including Manguin. While perhaps less overtly turbulent than Van Gogh, Manguin embraced the idea that color could convey feeling and create mood independently of naturalistic representation. This blend of Impressionist light, Cézannian structure, and Van Gogh's expressive potential formed the rich soil from which Manguin's Fauvist style would grow.

The Emergence of Fauvism

The year 1905 marked a watershed moment in modern art history with the Salon d'Automne exhibition in Paris. Manguin, alongside his friends Matisse, Camoin, and Marquet, as well as other like-minded artists such as André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck, exhibited works characterized by startlingly bold colors and seemingly wild execution. Their paintings were grouped together in Salle VII (Room 7) of the exhibition.

Standing amidst these canvases was a sculpture in a relatively traditional, Renaissance-inspired style. The stark contrast prompted the art critic Louis Vauxcelles to famously exclaim, "Donatello au milieu des fauves!" ("Donatello among the wild beasts!"). The term "Fauves" (wild beasts) stuck, initially intended as derogatory but quickly adopted by the artists themselves. Fauvism, though short-lived as a formal movement (roughly 1905-1908), represented the first major avant-garde art movement of the 20th century.

Manguin was a central figure in this explosion of color. He exhibited five paintings at this seminal 1905 Salon, contributing significantly to the impact of the "cage aux fauves." Fauvism prioritized emotional expression over realistic depiction. Color was liberated from its descriptive role and used arbitrarily to convey the artist's subjective experience of the subject. Form was simplified, perspective often flattened, and brushwork was vigorous and direct. Manguin fully embraced these tenets, using color to build form and express the sheer joy he found in the world around him.

Manguin's Distinctive Fauvist Style

While sharing the core principles of Fauvism with his contemporaries, Henri Manguin developed a distinctive artistic voice within the movement. His work is often characterized by a particular sensuousness and harmony that sets it apart. Unlike the sometimes jarring juxtapositions of Vlaminck or the more rigorously structured compositions of Derain, Manguin's Fauvism often feels gentler, more lyrical.

A key feature of his style is a preference for flowing, curvilinear lines over harsh angles or straight edges. His compositions frequently employ arabesques and undulating forms that contribute to a sense of ease and grace. This rhythmic quality is evident in his landscapes, nudes, and still lifes alike. Color and shape seem to echo each other, creating a unified and harmonious whole, even when the colors themselves are intensely vibrant.

His palette, while undeniably Fauvist in its brightness and non-naturalism, often favored warmer tones and more harmonious combinations compared to some of his peers. He excelled at capturing the brilliant light of the Mediterranean, translating it into canvases saturated with yellows, oranges, pinks, blues, and greens. This emphasis on pleasure, beauty, and the agreeable aspects of life led to his style being described as "la peinture voluptueuse" (voluptuous painting) or, more simply, the "painting of happiness." He sought to communicate delight rather than angst, finding Fauvism's expressive potential perfectly suited to celebrating the visual world.

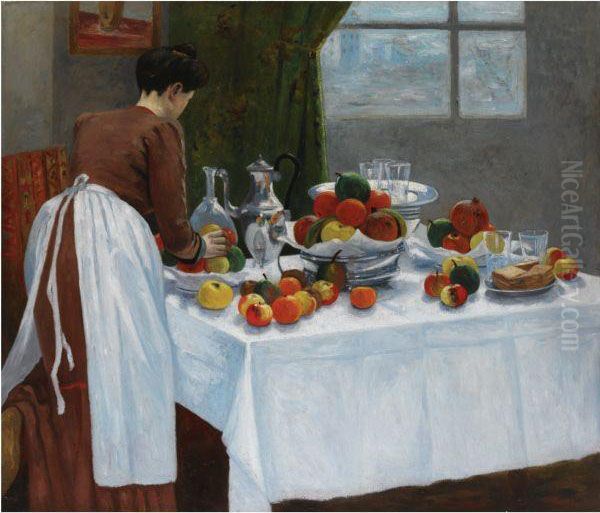

Enduring Themes: Landscapes, Nudes, and Domestic Life

Throughout his career, Manguin consistently returned to a set of core themes that allowed him to explore his fascination with color, light, and form. Mediterranean landscapes were perhaps his most favored subject. Drawn to the intense sunlight, vibrant vegetation, and azure waters of the South of France, he produced numerous canvases depicting coastal views, gardens, and sun-drenched scenery. These landscapes are quintessential Manguin, radiating warmth and vitality.

The female nude was another central theme. Manguin approached the nude with a sensuousness reminiscent of Renoir, but filtered through a Fauvist lens. His nudes are often set in idyllic landscapes or intimate interiors, their forms simplified and rendered in warm, luminous colors. Unlike the sometimes confrontational nudes of Matisse or Kees van Dongen, Manguin's figures typically exude a sense of relaxed tranquility and classical poise, albeit expressed with modern chromatic freedom. His wife, Jeanne, was a frequent model, and these works often possess a tender intimacy.

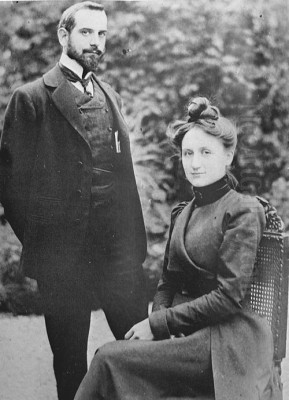

Still life provided another avenue for exploring pure color and form. Manguin arranged flowers, fruits, and objects in compositions that allowed for bold color harmonies and decorative arrangements. Works like The Vanilla Branch showcase his skill in balancing intense hues and creating visually engaging surfaces. Additionally, scenes of domestic life, often featuring Jeanne and their children (Claude, Pierre, Jean, and Louis), appear in his oeuvre, imbued with the same warmth and vibrant color that characterize his other subjects. His marriage to Jeanne Carré in 1899 provided not only personal happiness but also a constant source of artistic inspiration for over three decades.

Saint-Tropez: A Haven of Light and Color

The South of France, particularly the coastal town of Saint-Tropez, played a pivotal role in Henri Manguin's life and art. He first visited the region in 1904, drawn by the accounts of fellow artists and the allure of its legendary light. He was immediately captivated. The brilliant sunshine, the lush Mediterranean vegetation, the sparkling sea, and the relaxed pace of life provided an inexhaustible source of inspiration that perfectly suited his artistic temperament.

During this initial visit, Manguin spent time with the Neo-Impressionist painter Paul Signac, who had settled in Saint-Tropez some years earlier and acted as a magnet for other artists. Signac's pointillist technique, with its systematic application of color dots, was different from Manguin's approach, but both artists shared a profound interest in the scientific and expressive properties of color and light. Manguin also formed friendships with other artists associated with the South, such as Henri-Edmond Cross, another prominent Neo-Impressionist based nearby.

Manguin returned to Saint-Tropez frequently, often spending long summers there painting en plein air. He traveled extensively throughout the South with friends like Albert Marquet, exploring different landscapes and capturing their essence in vibrant canvases. The region became synonymous with his art, providing the setting for many of his most iconic Fauvist works. Eventually, later in his life, Manguin made Saint-Tropez his permanent home, solidifying his deep connection to the place that had so profoundly shaped his artistic vision. He died there in 1949, surrounded by the landscapes he loved to paint.

Career Development, Recognition, and Connections

Manguin began exhibiting his work early in his career, quickly gaining visibility within the Parisian art scene. He participated in the Salon des Indépendants starting in 1902 and the Salon d'Automne from 1903 onwards. These large, juryless or jury-selected exhibitions were crucial venues for avant-garde artists to showcase their work to the public and critics. His participation in the landmark 1905 Salon d'Automne cemented his reputation as a leading Fauve.

His talent attracted the attention of discerning collectors and dealers. The collector Jacques-Emile Blot acquired some of his works as early as 1906. Manguin's friendships with artists like Henri-Edmond Cross and Félix Vallotton (a prominent member of the Nabis group) also proved beneficial, helping him connect with important patrons and expanding his network within the art world. Vallotton, known for his sharp compositions and distinct style, represented a different facet of the post-Impressionist landscape, highlighting the diverse connections Manguin maintained.

While perhaps not achieving the same level of international fame during his lifetime as his close friend Matisse, Manguin enjoyed consistent recognition and success. His work was included in various exhibitions both in France and abroad, including a notable showing in Russia in 1911. He maintained friendships with a wide circle of artists beyond the core Fauve group, including Georges Rouault (another fellow student from Moreau's studio, known for his powerful, expressive style) and figures like Jules Pascin and Walter Lathuille, reflecting his engagement with the broader artistic currents of his time.

Notable Works: A Glimpse into Manguin's World

Several paintings stand out as representative examples of Henri Manguin's artistic achievements and characteristic style:

Le Palais des Papes à Avignon (The Palace of the Popes, Avignon): This work exemplifies his approach to landscape painting. Depicting the famous historical landmark in the South of France, Manguin transforms the scene through his Fauvist palette. The architectural forms are simplified, rendered in warm yellows, oranges, and pinks, set against a vibrant blue sky. The painting captures the intense light and atmosphere of Provence with characteristic energy and bold color choices, prioritizing emotional impact over topographical accuracy.

Vue de Saint-Tropez depuis la Villa Demière, Cavalière (View of Saint-Tropez from the Villa Demière, Cavalière - likely related to the cited "Vue de la maison de Cavalière à Saint-Tropez"): Many of Manguin's works capture views of or near Saint-Tropez. Paintings like this showcase his sensitivity to the nuances of Mediterranean light and his ability to translate the dazzling coastal scenery into harmonious compositions. Expect vibrant blues for the sea and sky, rich greens and ochres for the landscape, and perhaps the terracotta roofs rendered in bright orange or red, all unified by his fluid brushwork and sense of atmospheric warmth.

Le Rameau de vanille (The Vanilla Branch): This still life demonstrates Manguin's mastery of color harmony and composition within a more intimate genre. While the exact subject might be simple – perhaps a sprig of vanilla or a similarly exotic plant – Manguin uses it as a vehicle for exploring relationships between color, shape, and texture. Such works highlight his decorative sense and his ability to find beauty and painterly potential in everyday objects, imbuing them with Fauvist vitality.

Jeanne (Portrait of Jeanne): Manguin painted numerous portraits of his wife, Jeanne. These works often convey a sense of intimacy and affection. Rendered in his characteristic style, Jeanne's features might be simplified, but the focus is on capturing her presence through warm, luminous color and gentle, flowing lines. These portraits blend Fauvist boldness with a tender observation, reflecting the importance of his personal life as a source of artistic inspiration.

These examples illustrate the core elements of Manguin's art: his love for the Mediterranean landscape, his sensuous depiction of the human form, his skill in still life, and the overarching presence of vibrant color and joyful expression.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

Henri Manguin continued to paint prolifically throughout his life. While the intense, collective fervor of Fauvism subsided after about 1908, Manguin remained faithful to its core principles of expressive color and simplified form, albeit with perhaps a greater emphasis on harmony and structure in his later years. He continued to explore his favorite themes, particularly the landscapes around Saint-Tropez, where he eventually settled permanently.

His dedication to his craft resulted in a large and consistent body of work. Although sometimes overshadowed in art historical narratives by the more radical innovations of Matisse or the brief, intense careers of other Fauves, Manguin holds a secure place as one of the movement's most appealing and accomplished practitioners. His art consistently radiates a sense of well-being, optimism, and profound appreciation for the beauty of the natural world and the pleasures of life.

Today, Manguin's paintings are held in prestigious museum collections around the world, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, and the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, among others. His works continue to be sought after by collectors and admired by the public for their vibrant color, appealing subjects, and enduring charm. He is recognized not only for his contribution to Fauvism but also as an artist who successfully forged a personal style that celebrated light, color, and happiness, leaving behind a legacy of visually delightful and emotionally resonant art. His influence can be seen in later artists who prioritized color and expressive freedom.

Conclusion: The Painter of Voluptuous Joy

Henri Charles Manguin remains a vital figure in the story of modern art. As a founding member of the Fauvist movement, he played a key role in liberating color from its traditional descriptive function, paving the way for future artistic experimentation. His unique contribution lies in his ability to harness the radical potential of Fauvism to express not angst or turmoil, but rather a profound sense of joy, harmony, and sensuous pleasure in the world. His sun-drenched landscapes of the Mediterranean, his serene nudes, and his vibrant still lifes all testify to his mastery of color and his optimistic vision. Manguin's art is a celebration of life, rendered with a characteristic warmth and fluidity that continues to captivate viewers today, securing his position as the enduring "painter of happiness" within the Fauvist circle and beyond.