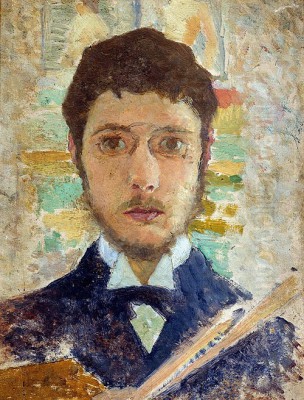

Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947) stands as a unique and pivotal figure in the transition from 19th-century Impressionism to the multifaceted landscape of 20th-century modern art. A French painter, illustrator, and printmaker, he is celebrated for his intensely personal vision, his extraordinary command of color, and his ability to transform intimate domestic scenes and sun-drenched landscapes into shimmering tapestries of light and emotion. Though associated with the Post-Impressionist group Les Nabis in his early career, Bonnard forged a path distinctly his own, creating a body of work that continues to captivate viewers with its sensory richness and quiet complexity.

Early Life and the Call to Art

Born in Fontenay-aux-Roses, a suburb of Paris, on October 3, 1867, Pierre Eugène Alfred Bonnard came from a comfortable middle-class background. His father, a prominent official in the French Ministry of War, initially guided his son towards a more conventional career path. Bonnard dutifully pursued a law degree in Paris, even briefly practicing as a barrister. However, the allure of art proved irresistible. While studying law, he also attended evening classes at the École des Beaux-Arts, though he failed the competition to enter the main painting course.

More formative was his time spent at the Académie Julian, a private art school known for its less rigid atmosphere compared to the official École. It was here, around 1888, that Bonnard encountered a group of like-minded young artists who would soon change the course of his life and contribute significantly to the Parisian avant-garde. Among them were Paul Sérusier, Maurice Denis, Édouard Vuillard, and Ker-Xavier Roussel. This period marked the definitive shift from law to a life dedicated entirely to art, a decision spurred perhaps by the successful sale of a poster design for France-Champagne in 1889.

The Nabi Adventure

The encounters at the Académie Julian laid the groundwork for the formation of Les Nabis (Hebrew for "prophets"). This short-lived but influential group coalesced around Paul Sérusier, who had returned from Pont-Aven bearing the lessons learned from Paul Gauguin. Sérusier's small painting, The Talisman (1888), painted under Gauguin's direct guidance, became a foundational object for the group, embodying Gauguin's principles of Synthetism – the use of flat planes of bold, often non-naturalistic color, strong outlines, and simplified forms to convey subjective feeling rather than objective reality.

The Nabis, including Bonnard, Maurice Denis (the group's primary theorist), Édouard Vuillard, and Ker-Xavier Roussel, embraced these ideas. They sought to break down the hierarchy between fine art and decorative arts, applying their aesthetic principles to painting, printmaking, poster design, theatre sets, stained glass, and textiles. They were deeply influenced by Japanese Ukiyo-e prints (Japonisme), admiring their flattened perspectives, asymmetrical compositions, decorative patterning, and focus on everyday life. Bonnard, in particular, absorbed these lessons, earning the nickname "le Nabi très japonard" (the very Japanese Nabi).

During his Nabi phase, Bonnard produced striking posters, illustrations, and lithographs, such as the four-panel screen Nannies' Promenade, Frieze of Carriages (1899). His paintings from this period often feature flattened space, decorative arabesques, and a muted but sophisticated palette, exploring themes of Parisian life and intimate interiors. He shared this focus on intimate domestic scenes with his close friend Édouard Vuillard, leading to both being labelled "Intimists."

Intimism and the Domestic Sphere

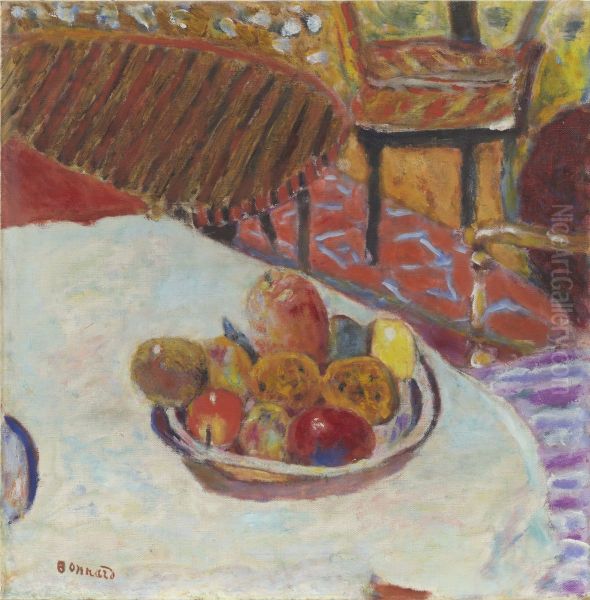

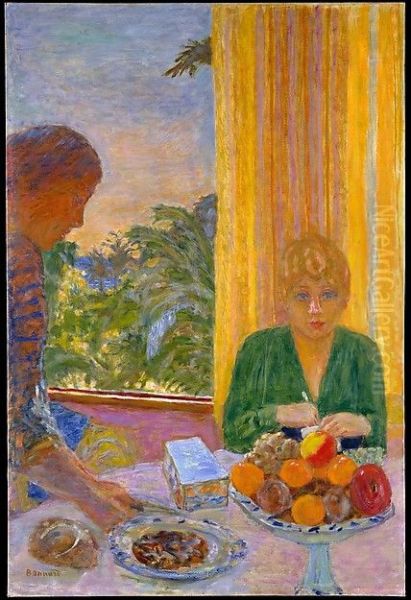

As the Nabi group gradually dispersed around 1900, Bonnard's art evolved. While retaining the decorative sensibility and the influence of Japanese prints, his focus sharpened intensely on his immediate surroundings – the intimate spaces of domestic life. His subjects became the quiet moments: figures at a table, interiors viewed through doorways, gardens glimpsed through windows, and, most famously, the solitary figure of a woman bathing or dressing.

This shift coincided with the entrance into his life of Marthe de Méligny, who became his lifelong companion and primary model. They met in 1893, and she would feature in hundreds of his paintings, drawings, and prints over the next five decades. Bonnard's depictions of Marthe and their shared environments are rarely straightforward representations. Instead, they are filtered through memory and emotion, imbued with a sense of mystery and psychological depth. He often used complex compositions, cropping figures unexpectedly, employing unusual vantage points, and using mirrors or windows to fragment and layer the space, much like Edgar Degas had done, though Bonnard's aim was less about capturing fleeting movement and more about constructing a sensory, remembered reality.

His paintings from this period, such as The Dining Room (c. 1913) or Bowl of Fruit, exemplify this Intimist approach. The subject matter is simple, yet the treatment is complex. Color begins to take precedence, light floods the scenes, and the boundaries between objects and figures often dissolve into a vibrant, unified surface. Bonnard wasn't merely documenting his life; he was transforming it into a world of heightened sensation.

Marthe: Muse and Mystery

The relationship between Pierre Bonnard and Marthe de Méligny is central to understanding his art and life. When they met, she introduced herself as Marthe de Méligny, an orphan of noble Italian heritage. It was only decades later, when they finally married in 1925, that Bonnard discovered her real name was Maria Boursin and she came from a modest background. This element of mystery seems woven into Bonnard's depictions of her.

Marthe became the subject of an extraordinary number of works, perhaps most notably the series of paintings depicting her in the bath. These works, created over many years, show Marthe immersed in water, the light refracting, the colors of the tiles and water creating an almost abstract mosaic around her form. Far from being simple nudes, these paintings explore themes of solitude, ritual, and the passage of time. Marthe suffered from various health issues, possibly requiring hydrotherapy, which may partly explain the prevalence of these scenes. Yet, Bonnard transforms the therapeutic ritual into moments of profound, dreamlike beauty, as seen in works like Nude in the Bath (1936).

Their life together, primarily spent in various houses in Normandy and later in the South of France, provided the backdrop for his art. While Marthe was his central muse, their relationship was complex. Bonnard had relationships with other women, most notably Renée Monchaty, a young model he painted. Tragically, Monchaty committed suicide in Rome in 1925, shortly after Bonnard finally married Marthe. This personal turmoil adds another layer to the seemingly tranquil domestic scenes Bonnard painted. Marthe herself died in 1942, leaving Bonnard profoundly affected for the remaining five years of his life.

Mastery of Color and Light

If there is one defining characteristic of Bonnard's art, it is his extraordinary use of color. He moved far beyond the Impressionists' attempts to capture the fleeting effects of natural light. For Bonnard, color became an independent, expressive force, capable of conveying emotion, structuring space, and creating sheer sensory delight. His palettes are often unexpected, juxtaposing warm and cool tones – violets next to yellows, oranges against blues – to create a shimmering, vibrant effect.

He famously worked from memory, making small sketches on site or from life, but developing the final paintings in the solitude of his studio. This allowed him to detach color from literal description and use it subjectively. He would pin unstretched canvases to the wall and work on multiple paintings simultaneously, slowly building up layers of rich, textured color. He often let paintings sit for long periods, returning to them to adjust hues until the chromatic harmony satisfied his eye. This meticulous process resulted in surfaces that seem to pulse with light and energy.

His move to the South of France, eventually settling in Le Cannet above Cannes in 1926, had a profound impact on his palette. The intense Mediterranean light led to even more radiant and high-keyed color harmonies. Works from this later period often feature dazzling yellows, intense blues, vibrant pinks, and luminous whites, capturing the sun-drenched atmosphere of his garden and the surrounding landscape. He shared this love of southern light with his contemporary and friend, Henri Matisse, though their application of color remained distinct – Matisse favouring bold, flat areas, while Bonnard preferred a more broken, shimmering application.

Beyond Impressionism: A Unique Vision

While Bonnard emerged from the milieu of Post-Impressionism and learned much from Impressionists like Claude Monet and Edgar Degas, he cannot be neatly categorized. He resisted the major avant-garde movements of the early 20th century, such as Fauvism and Cubism. While his friend Matisse became a leader of the Fauves with their explosive, arbitrary color, Bonnard's color, though equally bold, remained tied to sensation and the memory of observed reality.

He also stood apart from the structural revolution of Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Picasso, who famously dismissed Bonnard's work as "a potpourri of indecision," prioritized formal analysis, deconstruction, and intellectual rigor. Bonnard, conversely, remained dedicated to the world of visual sensation, perception, and intimate feeling. He was less interested in dissecting form than in capturing the immersive experience of seeing, the way light dissolves edges, and how memory colors perception. His compositions, while complex and sometimes spatially ambiguous, serve the overall sensory effect rather than a theoretical framework.

He admired the structural solidity of Paul Cézanne, another towering figure of Post-Impressionism, but Bonnard's own approach was more fluid and intuitive. He described his aim as capturing "the transcription of the adventures of the optic nerve." His work represents a unique path in modern art, one that valued continuity with certain aspects of the Impressionist tradition while pushing color and composition into new, deeply personal territories. He remained committed to representational painting but infused it with a modern sensibility focused on subjective experience.

Landscapes and the Lure of the South

Although best known for his intimate interiors, Bonnard was also a dedicated landscape painter throughout his career. His early landscapes often reflect the softer light and more muted tones of northern France. However, his move to Vernon in Normandy and later, definitively, to Le Cannet on the French Riviera, transformed his approach to landscape.

The intense light and vibrant colors of the Midi (the South of France) became central subjects. His garden at Le Cannet, with its almond trees, mimosas, and views towards the Esterel mountains, featured repeatedly in his later works. These are not topographical records but immersive environments where foliage, flowers, sky, and distant hills merge into dazzling patterns of color. Works like Terrace at Vernon (c. 1920-39) or landscapes painted from his villa, Le Bosquet, showcase this mature style.

He often framed landscape views through windows or doorways, integrating the interior space with the exterior world. This technique emphasizes the act of looking itself and reinforces the personal, subjective nature of his vision. The landscape becomes an extension of the intimate domestic world, bathed in the same shimmering, color-saturated light. He captured the heat, the brilliance, and the almost overwhelming sensory richness of the southern French environment.

Later Years and the "Infra-Thin"

Bonnard's late work, created primarily at Le Cannet from the late 1920s until his death in 1947, represents a culmination of his artistic concerns. His colors became even more intense and daring, sometimes bordering on the abstract, yet always grounded in observed reality filtered through memory. Compositions grew more complex, with space tilting and flattening, perspectives shifting within a single canvas.

Critics and art historians have sometimes used the term "infra-thin" (infra-mince), borrowed from Marcel Duchamp, to describe the subtle, almost imperceptible shifts and vibrations of color and light in Bonnard's late work. It speaks to his ability to capture fleeting sensations, the shimmer of light on surfaces, and the way colors influence each other in close proximity. Paintings like The White Cupboard (1931) or Corner of the Table (c. 1935) exemplify this late style, where everyday objects are transfigured by color and light into something extraordinary.

He also continued to paint self-portraits in his later years. These works are often starkly honest, depicting the aging artist with a sense of vulnerability and introspection, sometimes with a touch of self-deprecation that contrasts sharply with the assertive self-portraits of many of his contemporaries. He continued working diligently even during the difficult years of World War II, finding solace and purpose in his art. He died at Le Cannet on January 23, 1947.

Controversies and Criticisms

Despite his eventual recognition as a major figure, Bonnard's path was not without controversy or criticism. During his lifetime and for some time after, his work was sometimes seen as retardataire, out of step with the more radical avant-garde movements. His focus on intimate, seemingly bourgeois subjects and his commitment to a form of representational painting, albeit highly subjective, led some critics, including the influential Clement Greenberg, to initially underestimate his importance in the narrative of modernism.

The sharpest criticism famously came from Pablo Picasso, who saw Bonnard's nuanced, shimmering surfaces and complex color harmonies as lacking the decisive structure and revolutionary edge he valued. This critique highlights the differing paths modern art took in the 20th century – the analytical and revolutionary versus the sensory and evolutionary.

Furthermore, Bonnard's estate became the subject of protracted legal battles after his death. Because he died intestate (without a will), and the legal status of his marriage to Marthe (due to her concealed identity) was complex, ownership of the hundreds of works remaining in his studio was fiercely contested for years. This unfortunately kept many works out of the public eye and complicated the process of fully assessing his legacy immediately following his death.

Friendships and Artistic Circles

While often perceived as a solitary figure, particularly in his later years, Bonnard maintained important connections within the art world. His early association with the Nabis (Sérusier, Denis, Vuillard, Roussel) was crucial. His lifelong friendship with Édouard Vuillard was particularly close, built on shared artistic sensibilities, though their styles diverged over time.

Perhaps his most significant artistic friendship was with Henri Matisse. Despite their stylistic differences, the two artists held each other in high esteem for over forty years, maintaining a warm correspondence, particularly when both lived in the South of France. They respected each other's dedication to color and light, finding common ground despite their different approaches. Bonnard also had connections with other Symbolist artists like Odilon Redon and maintained relationships with important dealers, most notably Ambroise Vollard, who supported him early in his career.

Legacy and Market Recognition

Today, Pierre Bonnard's reputation is secure. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest colorists of the 20th century and a master of intimate, psychologically resonant painting. Museums around the world hold significant collections of his work, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Tate Modern in London, and particularly The Phillips Collection in Washington D.C., which boasts one of the largest and finest collections of his paintings outside France.

His work commands high prices on the art market. Major paintings like Terrace à Vernon have sold for millions of dollars at auction, reflecting the strong demand from collectors. Retrospectives of his work continue to draw large crowds, demonstrating his enduring appeal to both art historians and the general public.

Bonnard's influence can be seen in the work of later painters who valued color, light, and sensory experience, though he founded no school. He remains a "painter's painter," admired for his technical mastery, his unique vision, and his unwavering dedication to translating his personal world into canvases that radiate with life and light.

Conclusion

Pierre Bonnard carved a unique niche in the history of modern art. Emerging from Post-Impressionism and the Nabi movement, he developed a deeply personal style characterized by luminous color, intimate subject matter, and a profound sensitivity to the nuances of perception and memory. He transformed the everyday world – a breakfast table, a woman in a bath, a sunlit garden – into extraordinary visual experiences. Resisting easy categorization and the dominant trends of the avant-garde, he pursued his own vision with quiet determination. His legacy lies in his masterful ability to dissolve the world into light and color, creating paintings that offer not just a view, but an immersive sensory embrace, capturing the beauty, mystery, and fleeting moments of life itself.