Louis Auguste Mathieu Legrand (1863-1951) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in French art at the turn of the 20th century. A prodigious printmaker, draftsman, and occasional painter, Legrand dedicated his career to capturing the multifaceted, often risqué, realities of Parisian society, particularly its vibrant nightlife, the world of entertainment, and the intimate lives of its women. His work, characterized by keen observation, technical mastery, and a subtle blend of empathy and satire, offers a unique window into the Belle Époque and beyond.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Dijon, France, on September 29, 1863, Louis Legrand's early life set him on a path somewhat removed from the traditional academic art world. He initially worked as a bank teller in his hometown. However, his artistic inclinations soon led him to evening classes at the École des Beaux-Arts in Dijon, where he began to hone his drawing skills. This foundational training, though perhaps less prestigious than a Parisian academy education from the outset, provided him with the essential tools for his future endeavors.

The allure of Paris, the undisputed art capital of the world at the time, proved irresistible. Around 1884, Legrand made the pivotal decision to move to the city. This relocation was crucial, immersing him in an environment teeming with artistic innovation, cultural ferment, and the very subjects that would come to define his oeuvre. Paris was a city of dazzling contrasts, from the opulent opera houses and grand boulevards to the bohemian cabarets of Montmartre and the hidden lives of its working class – all of which would eventually find their way into Legrand's art.

The Crucial Encounter with Félicien Rops

A defining moment in Legrand's artistic development came with his encounter with the iconoclastic Belgian artist Félicien Rops. Rops, known for his Symbolist and often erotically charged etchings and drawings, was a master of printmaking techniques. Under Rops's tutelage, Legrand was introduced to the intricacies of etching and drypoint. This mentorship was transformative. Rops not only imparted technical knowledge but also likely encouraged Legrand's interest in unconventional, sometimes provocative, subject matter.

The techniques of etching and drypoint became Legrand's primary modes of expression. Etching, with its capacity for fine lines and rich tonal variations through acid biting, and drypoint, which creates a velvety, burred line by incising directly into the copper plate, allowed him to achieve a remarkable range of textures and moods. He quickly mastered these demanding media, developing a distinctive style that was both technically proficient and highly expressive. This mastery would set him apart and become the hallmark of his artistic identity.

Themes and Subjects: A Mirror to Parisian Society

Louis Legrand's art is inextricably linked to the social fabric of Paris during the Belle Époque (roughly 1871-1914) and the subsequent decades. He was a keen observer of human nature and the urban spectacle, drawing his inspiration from the city's diverse inhabitants and their varied pursuits.

The World of Dance and Theatre

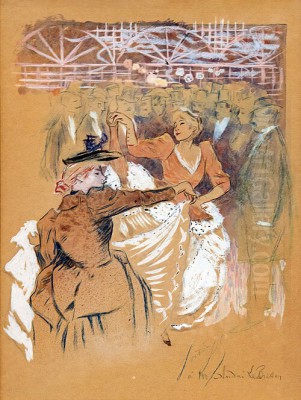

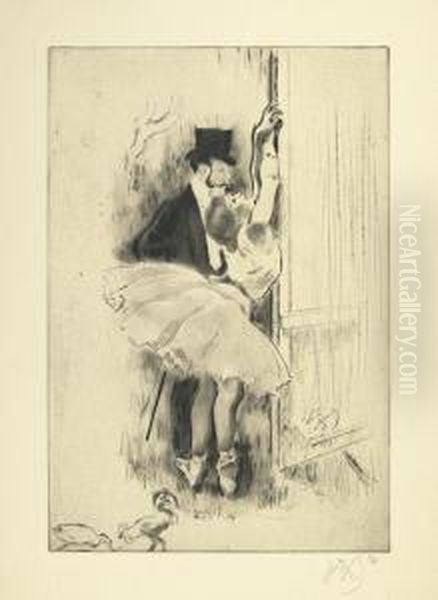

The world of dance, particularly ballet, was a recurring and central theme in Legrand's work. Like Edgar Degas before him, Legrand was fascinated by dancers, both on stage and behind the scenes. However, his perspective often differed from Degas's more detached observations. Legrand's depictions frequently emphasized the grueling work, the youthful vulnerability, and sometimes the subtle eroticism associated with the life of a dancer.

He portrayed young ballet students in rehearsal, their bodies contorting in demanding poses, their faces reflecting concentration or fatigue. Works like Les petites du ballet (The Little Ones of the Ballet) capture the atmosphere of the dance studio, the rigorous training, and the aspirations of these young performers. He also depicted dancers in moments of repose, adjusting their costumes, or in the wings, awaiting their cue. Entrée de Scène (Stage Entrance) likely captures this anticipatory moment, hinting at the glamour and the grit of theatrical life. His interest extended to other forms of popular entertainment, including café-concert singers and actresses, whose public personas and private moments he explored with equal acuity.

Cafés, Bars, and the Social Milieu

Parisian cafés, bars, and restaurants were vibrant hubs of social interaction, and Legrand was a diligent chronicler of these scenes. He captured the lively ambiance, the diverse clientele, and the fleeting encounters that characterized these establishments. Au Café - La Négresse (At the Café - The Black Woman), part of his Les Barres series (1908), is a notable example, reflecting the cosmopolitan nature of Paris and perhaps hinting at the complex social dynamics of the era.

His depictions often included figures from various social strata, from elegant bourgeois couples to working-class individuals and bohemian artists. These scenes are not merely documentary; they are imbued with a sense of atmosphere and psychological insight. Legrand had an eye for the subtle gestures, glances, and interactions that reveal underlying narratives and social commentaries. He was interested in the human comedy played out in these public spaces, often with a touch of gentle irony or poignant observation.

Intimate Portraits and the Female Form

The female form was a constant preoccupation for Legrand, and he approached it with a sensitivity that ranged from tender observation to frank sensuality. He created numerous studies of women in intimate settings – at their toilette, resting, or engaged in quiet contemplation. Works like La grande sœur (The Big Sister, 1898) suggest a narrative of domesticity or personal relationships, rendered with delicate lines and an understanding of human emotion.

His portrayal of women often challenged conventional notions of beauty and propriety. He depicted not only elegant society ladies but also working-class women, laundresses, shop girls, and figures from the demimonde. There is often a sense of realism and an absence of idealization in these works, presenting women with a directness that could be both alluring and unsettling to contemporary audiences. Petite Marcheuse (Little Streetwalker) and Incognito hint at the more clandestine aspects of Parisian life, subjects that Legrand, like his contemporary Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, did not shy away from.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Louis Legrand's artistic style is characterized by its strong draftsmanship, expressive use of line, and sophisticated handling of light and shadow. While primarily a printmaker, his approach was painterly in its richness and depth.

Mastery of Etching and Drypoint

Legrand's command of etching and drypoint was exceptional. He exploited the unique qualities of each technique to create works of remarkable subtlety and power. His drypoints are known for their rich, velvety blacks and soft, atmospheric lines, ideal for conveying intimate moods and delicate textures. His etchings display a versatile range, from fine, precise lines to bold, expressive marks, allowing him to capture both intricate details and broader effects. He often combined techniques, or used different states of a plate, to achieve the desired result, demonstrating a printmaker's deep understanding of process.

Realism Tinged with Symbolism and Satire

While rooted in realism, Legrand's work often incorporated elements of Symbolism and a distinct satirical edge. His realistic depiction of Parisian life was not merely a passive recording of facts; it was filtered through his personal vision and often carried a deeper meaning or social critique. He was adept at capturing the psychological nuances of his subjects, hinting at their inner lives and the social forces shaping them.

His satirical bent is evident in his portrayals of socialites, performers, and the interactions between different classes. This satirical element, however, was usually tempered with a degree of empathy, preventing his work from becoming merely caricatural. He shared this observational acuity and penchant for social commentary with artists like Jean-Louis Forain, with whom he sometimes collaborated or shared thematic concerns.

Influence of Art Nouveau

Legrand's career coincided with the flourishing of Art Nouveau, and its influence can be discerned in some of his works, particularly in the flowing lines, decorative compositions, and stylized forms. His first major solo exhibition in 1896 was held at Siegfried Bing's "L'Art Nouveau" gallery, a clear indication of his association with the movement. While not a purely Art Nouveau artist in the vein of Alphonse Mucha or Hector Guimard, Legrand absorbed aspects of its aesthetic, integrating them into his own distinctive style. This is particularly evident in some of his more decorative compositions and his elegant portrayals of women.

Key Works and Series

Several works and series stand out in Louis Legrand's extensive oeuvre, showcasing his thematic concerns and technical prowess.

Poèmes à l'eau-de-vie (Poems in Brandy/Spirits of Wine, c. 1914): This significant publication, issued by the renowned publisher Gustave Pellet, featured a collection of 30 etchings and 45 woodcuts by Legrand. The title itself suggests a connection to the bohemian, perhaps decadent, aspects of Parisian life, a theme often explored by poets like Charles Baudelaire and Paul Verlaine, whose spirit seems to echo in Legrand's visual interpretations. Pellet was also the publisher for Toulouse-Lautrec, indicating the high regard in which Legrand's printmaking was held.

Les Barres (The Bars/Rails, 1908): This series, also published by Pellet, focused on scenes from Parisian bars and cafés. Au Café - La Négresse is a prime example from this series, demonstrating Legrand's interest in the diverse social tapestry of the city and his ability to create compelling narratives within everyday settings. The title could refer to the bar itself, or metaphorically to social barriers.

Individual Prints:

La grande sœur (The Big Sister, 1898): An etching that likely portrays a tender, intimate moment, showcasing Legrand's ability to convey emotion and narrative through subtle means.

Danseuse à l'éventail (Dancer with a Fan): This subject, popular among artists of the period including Degas and James McNeill Whistler, allowed Legrand to explore the elegance, movement, and exoticism associated with dance and feminine adornment.

Charles VI et son amie (Charles VI and His Mistress, 1908/09): This historical or allegorical subject is somewhat unusual among his more contemporary scenes but demonstrates his versatility and his engagement with broader artistic and literary themes. It might also carry a satirical or symbolic commentary relevant to his own time.

Incognito, Petite Marcheuse, and Entrée de Scène: These titles suggest narratives of anonymity, the demimonde, and the theatre, all central to Legrand's fascination with the hidden and performative aspects of Parisian life.

These works, among many others, highlight Legrand's consistent engagement with the human condition as observed through the lens of Parisian society. His prints were often produced in relatively small editions, making them prized by collectors.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Artistic Circle

Louis Legrand achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime. His participation in prestigious exhibitions and his connections within the Parisian art world attest to his standing.

His first solo exhibition at Bing's "L'Art Nouveau" gallery in 1896, featuring over 200 works, was a significant milestone, placing him firmly within the contemporary art scene. He regularly exhibited at the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, a key venue for artists seeking official recognition.

A testament to his international reputation was the silver medal he received at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900. In 1906, a major retrospective of his work, comprising over 300 prints, was held at the Musée Félicien Rops in Namur, Belgium, a fitting tribute given Rops's seminal influence on his career. Another important retrospective took place in 1911 at the Pavillon de Marsan (part of the Louvre) in Paris, showcasing his complete printed oeuvre to date. Such exhibitions solidified his reputation as a master printmaker.

Legrand moved within a vibrant artistic circle. His teacher, Félicien Rops, was a crucial early connection. His publisher, Gustave Pellet, linked him to other prominent artists of the avant-garde, most notably Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who also explored the nightlife of Montmartre, albeit with a bolder, more graphic style. Legrand's work shares thematic affinities with Jean-Louis Forain, known for his satirical drawings of Parisian society and legal scenes, and Théophile Steinlen, another chronicler of Montmartre and working-class life.

While Edgar Degas was an undeniable influence, particularly in the depiction of dancers, Legrand carved his own niche. Other contemporaries whose work resonates with aspects of Legrand's include Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, the Nabis artists who also excelled in printmaking and intimate scenes, though their style was more focused on color and pattern. The elegant drypoints of Paul César Helleu, depicting fashionable women, offer a point of comparison, though Legrand's scope was broader and often grittier. Even the work of Mary Cassatt, with her focus on women and children in intimate settings and her mastery of printmaking, shares some common ground. One might also consider the social commentary in the prints of Käthe Kollwitz, though her context was German and her tone generally more tragic. The poster art of Jules Chéret, celebrating Parisian entertainment, provides a backdrop to the world Legrand depicted.

Controversies and Social Commentary

Legrand's willingness to tackle risqué or socially critical themes did not go unnoticed and, at times, led to controversy. His art often delved into the less sanitized aspects of Parisian life, including prostitution and the exploitation of women, which could be challenging for conservative contemporary sensibilities.

A notable incident involved two of his satirical drawings which led to him being charged with obscenity. Although he was ultimately acquitted, the case highlights the provocative nature of some of his work and the tensions between artistic freedom and societal norms of the period. This willingness to confront uncomfortable truths and to use his art as a vehicle for social commentary, however subtle, adds another layer to his significance. He was not merely an entertainer but an observer with a critical eye, documenting the complexities and contradictions of his time. His depictions of young dancers, for instance, often hint at their vulnerability and the precariousness of their position, subtly critiquing the societal structures that shaped their lives.

Legacy and Scholarly Assessment

Louis Legrand's legacy rests primarily on his remarkable body of work as a printmaker. He was a master of etching and drypoint, techniques he used to create a vivid and enduring portrait of Parisian life at the turn of the 20th century. His work is valued for its technical skill, its observational acuity, and its nuanced portrayal of a complex society.

While perhaps not as widely known today as some of his more flamboyant contemporaries like Toulouse-Lautrec, Legrand's contributions are increasingly recognized by art historians and collectors. His prints are held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris, the British Museum in London, and various institutions in the United States.

The scholarly reassessment of his work has been aided by publications such as the Louis Legrand: Catalogue Raisonné compiled by Victor Arwas (published in 2006). Such comprehensive studies are crucial for understanding the full scope of an artist's production and for securing their place in art history. Arwas's work, in particular, has brought renewed attention to Legrand's skill and the breadth of his subject matter.

Legrand continued to work throughout the first half of the 20th century, adapting his style but remaining true to his core interest in the human figure and social observation. He passed away in Livry-Gargan, near Paris, in 1951, leaving behind a rich visual record of an era.

Conclusion

Louis Legrand was more than just a skilled technician; he was a sensitive and insightful interpreter of his time. His art provides a captivating journey through the streets, salons, theaters, and hidden corners of Paris, revealing the city's energy, its glamour, its inequalities, and its human dramas. From the graceful movements of ballet dancers to the knowing glances exchanged in a crowded café, Legrand captured the ephemeral moments of life with an artist's eye and a storyteller's heart. His mastery of printmaking allowed him to translate these observations into enduring images that continue to fascinate and engage viewers today, securing his position as a distinguished chronicler of the Belle Époque and a significant figure in the history of French printmaking. His work serves as a vital visual document, complementing the literary accounts of authors like Émile Zola or Guy de Maupassant, who also sought to capture the essence of Parisian life in all its complexity.