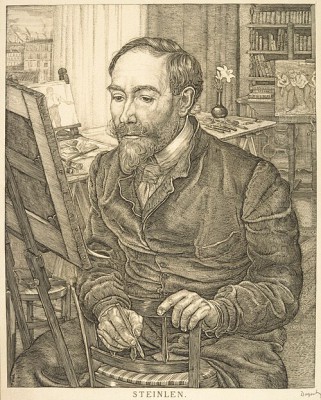

Théophile Alexandre Steinlen stands as a pivotal figure in the vibrant artistic landscape of late 19th and early 20th century Paris. Born in Lausanne, Switzerland, on November 10, 1859, he became a naturalized French citizen and one of the most prolific and socially conscious artists associated with the Art Nouveau movement and the bohemian spirit of Montmartre. His vast body of work, encompassing posters, paintings, illustrations, prints, and sculptures, offers an unparalleled visual chronicle of Parisian life, particularly the experiences of the working class, while his iconic depictions of cats have charmed audiences for generations. Steinlen passed away in Paris on December 13, 1923, leaving behind a legacy defined by artistic skill, empathy, and a keen eye for social commentary.

From Lausanne to the Butte Montmartre

Steinlen's early life in Switzerland hinted at an intellectual path rather than an artistic one. His family, rooted in artistic and scholarly traditions, initially encouraged him towards theology, leading him to study literature and philosophy at the University of Lausanne. However, the pull towards visual arts proved stronger. Encouragement from the Swiss painter François Bocion may have played a role in his decision to pursue art more seriously.

His formal artistic training began not in a traditional academy, but in the industrial setting of Mulhouse, in eastern France. In 1879, he took up an apprenticeship as a textile designer at a factory. This early exposure to industrial design likely honed his sense of pattern, line, and practical application, skills that would later inform his masterful poster work. Yet, the allure of Paris, the undisputed center of the art world at the time, was irresistible.

In 1881, Steinlen made the decisive move to the French capital. He settled in Montmartre, the hilly district overlooking Paris that was rapidly becoming the epicenter of bohemian life. It was a melting pot of artists, writers, musicians, performers, and revolutionaries, a place of cheap rents, lively cabarets, and artistic ferment. Here, Steinlen found his spiritual and artistic home, quickly integrating into the local community.

The Heart of Bohemia: Le Chat Noir

Montmartre provided Steinlen with not just a place to live, but a vibrant community and endless subject matter. He befriended fellow artists like Adolphe Willette, known for his Pierrot figures, and soon became deeply involved with the legendary cabaret, Le Chat Noir (The Black Cat). Founded in 1881 by Rodolphe Salis, Le Chat Noir was more than just a drinking establishment; it was a crucible of avant-garde performance, art, and literature, famous for its shadow theatre and satirical journal.

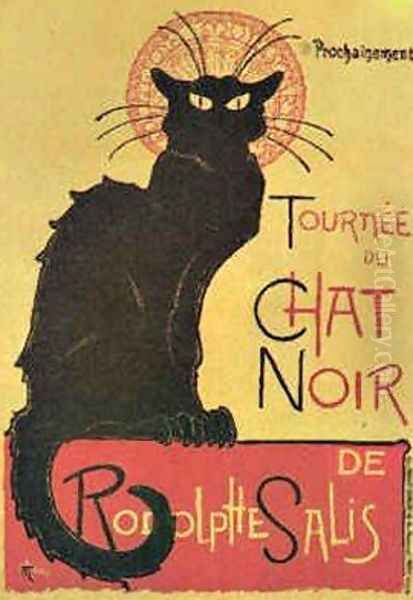

Steinlen became a regular, contributing illustrations and satirical cartoons to the cabaret's eponymous magazine and other associated publications like Le Mirliton, run by the famed chansonnier Aristide Bruant. His connection with Le Chat Noir was cemented by his creation of arguably the most famous cabaret poster of all time, Tournée du Chat Noir, promoting a tour by the cabaret's troupe. This iconic image, featuring a stark black cat with a halo against a contrasting background, perfectly captured the establishment's mystique and became synonymous with Montmartre's bohemian allure. His friendships within this circle extended to figures like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, another denizen of Montmartre renowned for his depictions of its nightlife.

A Distinctive Style: Art Nouveau, Realism, and Beyond

Steinlen's artistic style is a fascinating synthesis of various influences, resulting in a unique and recognizable visual language. He is most prominently associated with Art Nouveau, evident in the flowing, organic lines, flattened perspectives, and decorative qualities found in much of his work, especially the posters. Like his contemporary Alphonse Mucha, Steinlen mastered the integration of image and text, creating visually harmonious compositions.

However, his work transcends mere decoration. A strong undercurrent of Realism runs through his art, particularly in his depictions of everyday life. He drew inspiration from earlier masters of social observation like Honoré Daumier, and contemporaries who captured modern life, such as Edgar Degas and Édouard Manet. Steinlen possessed a remarkable ability to capture the gestures, postures, and expressions of ordinary Parisians with authenticity and empathy.

Furthermore, the influence of Japanese Ukiyo-e prints, which had swept through Paris and profoundly impacted artists like Degas, Mary Cassatt, and the Nabis group (including Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard), is visible in Steinlen's work. This can be seen in his bold outlines, asymmetrical compositions, and use of flat planes of color, techniques he adapted to his own ends. His style was less ethereal than Mucha's, often grittier and more grounded than Toulouse-Lautrec's, marked by a powerful linearity and a keen sense of design.

Chronicler of the People: Themes and Subjects

While capable of charming decorative work, the core of Steinlen's artistic project lay in his observation and depiction of Parisian society, particularly its less glamorous aspects. He turned his gaze towards the working class: laundresses bent over their tubs, weary factory workers returning home, street vendors hawking their wares, miners, fishermen, and the destitute seeking shelter. His portrayal was rarely sentimental; instead, it was imbued with a deep sense of empathy and a quiet dignity.

He captured the bustling energy of Montmartre's streets, the intimacy of its cafes, and the quiet moments of domestic life. His work serves as an invaluable record of the social fabric of Paris during the Belle Époque and into the early 20th century. Unlike artists focused solely on the bourgeoisie or the dazzling spectacle of the Moulin Rouge, Steinlen gave voice and visibility to the common people, highlighting their struggles and resilience.

His social conscience was sharp, and his work often carried critical undertones. He contributed illustrations to numerous satirical and politically engaged journals, including the anarchist-leaning L'Assiette au Beurre and socialist publications like Le Chambard Socialiste. Through powerful imagery, he addressed issues of poverty, labor exploitation, social injustice, and the growing tensions that would eventually erupt into war.

The Ubiquitous Cat

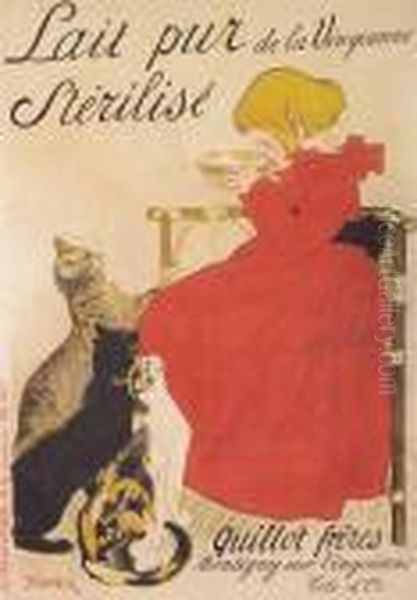

No discussion of Steinlen is complete without acknowledging his profound affinity for cats. They prowl, lounge, stretch, and stare out from countless drawings, prints, posters, and even sculptures. For Steinlen, the cat was more than just a household pet; it seemed to embody the independent, enigmatic, and slightly wild spirit of Montmartre itself. It was a symbol of freedom, poetry, and the bohemian lifestyle.

His depictions range from quick, fluid sketches capturing their movement and character with astonishing economy of line, to highly finished posters where they take center stage, like the iconic Chat Noir image. He observed them with a loving and precise eye, capturing their anatomy, postures, and distinct personalities. This fascination resulted in a body of feline imagery unparalleled in its scope and sensitivity, contributing significantly to his popular appeal then and now. His Swiss-French contemporary, Félix Vallotton, also known for his striking prints, occasionally depicted cats, but none with the sheer dedication and volume of Steinlen.

Master of Print and Poster

While Steinlen worked across various mediums, his contributions to printmaking and poster design are particularly significant. He was a master lithographer and etcher, producing an estimated 382 original prints and 115 etchings throughout his career. His prints often explored the same themes as his drawings and paintings – street scenes, workers, cats – but with the specific qualities afforded by the medium, such as rich blacks and expressive lines.

He was a leading figure during the golden age of the poster in Paris, a period when artists like Toulouse-Lautrec, Mucha, Bonnard, and Jules Chéret transformed street advertising into an art form. Steinlen's posters, advertising everything from cabarets and milk products (Lait pur Stérilisé) to theatrical performances and social causes, are characterized by their strong compositions, bold lines, effective use of color, and clear communication. They demonstrate his ability to combine artistic merit with commercial or social purpose. His work in this field significantly shaped the visual culture of Belle Époque Paris.

Key Works in Focus

Steinlen's vast output includes several particularly renowned works:

Tournée du Chat Noir: As mentioned, this 1896 poster is perhaps his most famous creation. Its striking design, featuring a stylized black cat with wide eyes and prominent whiskers set against a simple background with bold lettering, remains an enduring symbol of Montmartre's artistic heritage.

Les Terrassiers revenue de leur travail (Workers Returning from Work): This work exemplifies his focus on the laboring class. It depicts a group of construction workers, tools in hand, trudging home after a day's toil. The figures convey weariness and solidarity, rendered with Steinlen's characteristic empathy and realistic detail.

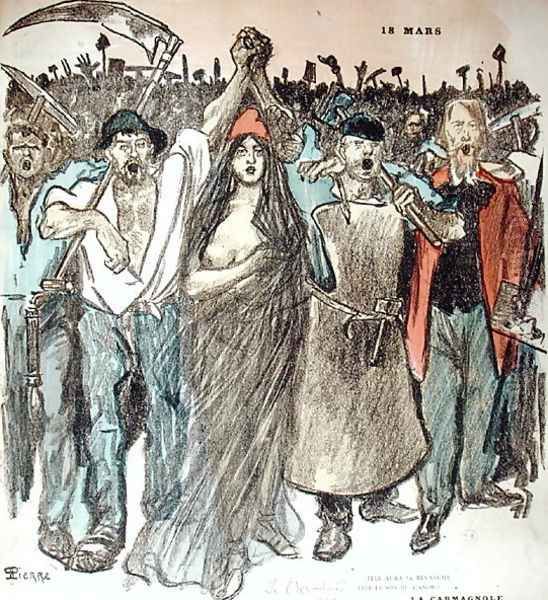

Le Cri des pavés (The Cry of the Pavement/Streets): A powerful image often interpreted as a commentary on social unrest and the memory of the Paris Commune. It depicts figures emerging from the cobblestones, suggesting the simmering discontent and suffering of the urban poor. This work highlights his willingness to engage with politically charged themes.

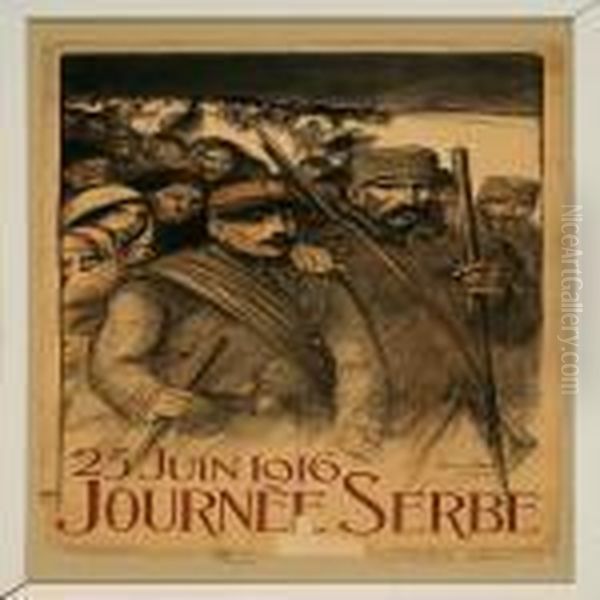

World War I Works: The outbreak of war in 1914 deeply affected Steinlen. He produced numerous works reflecting the conflict's impact, focusing not on heroic battles but on the suffering of soldiers and civilians. Posters like Journée Serbe (Serbian Day, 1916), created to raise funds for Serbian relief, depict the plight of refugees. Other works like Mobilization and The Exodus capture the disruption, fear, and loss experienced by ordinary people during the war, showcasing his consistent humanitarian concerns.

Political Engagement and Social Commentary

Steinlen was not an artist detached from the political currents of his time. He held strong sympathies for socialist and anarchist causes, believing art could be a tool for social change. This commitment is evident in his regular contributions to left-wing journals known for their sharp social critique.

His illustrations for publications like L'Assiette au Beurre and Le Chambard Socialiste often tackled controversial subjects head-on, satirizing politicians, industrialists, and the bourgeoisie, while championing the cause of the oppressed. Aware of the potential repercussions of such work, Steinlen sometimes published under pseudonyms, including "Treelan" and "Pierre," to protect himself while continuing his visual commentary. This places him in a lineage of socially engaged artists that includes Daumier and later figures who used graphic art for political expression, such as Jean-Louis Forain, another contemporary illustrator known for his social satire.

Later Life, Influence, and Legacy

In 1901, Steinlen formalized his connection to his adopted homeland by becoming a French citizen. He continued to live and work in Montmartre, remaining a respected figure in the Parisian art world. His influence extended to younger artists, including a young Pablo Picasso during his early years in Paris, who admired Steinlen's depictions of the poor and marginalized.

Throughout his career, Steinlen produced an astonishing volume of work, estimated at around 4,300 pieces in total. He exhibited regularly, including at the Salon des Indépendants. His dedication to his craft and his consistent focus on the human condition, whether expressed through the struggles of workers or the simple grace of a cat, earned him widespread recognition.

Théophile Alexandre Steinlen died in Paris in 1923 and was buried in the Cimetière Saint-Vincent in his beloved Montmartre. Today, his works are held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University (which holds a significant collection of his prints), the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., as well as numerous French institutions.

His legacy is multifaceted. He remains celebrated as a key proponent of Art Nouveau, particularly in the realm of poster design. His depictions of cats are iconic and continue to delight. Perhaps most importantly, he stands as a powerful social realist, an artist who used his considerable talents to document and comment upon the lives of ordinary Parisians, giving enduring visual form to their joys, sorrows, and struggles. He was a true chronicler of his time, an artist whose work resonates with humanity and artistic integrity.

Conclusion

Théophile Alexandre Steinlen occupies a unique and vital place in art history. Bridging the decorative elegance of Art Nouveau with the gritty realism of social commentary, he created a body of work that is both aesthetically compelling and deeply humane. As a master draftsman, printmaker, and poster artist, he shaped the visual identity of Belle Époque Paris. As an observer of life in Montmartre, he captured the spirit of a specific time and place with unparalleled empathy. From the iconic black cat of Le Chat Noir to the weary faces of Parisian laborers, Steinlen's art continues to speak to us, reminding us of the power of observation, the importance of social conscience, and the enduring beauty found in everyday life.