Henri-Jacques Evenepoel stands as a significant, albeit tragically short-lived, figure in the vibrant art world of late nineteenth-century Europe. A Belgian by nationality, his artistic journey predominantly unfolded in Paris, the pulsating heart of artistic innovation during the fin-de-siècle. Evenepoel's oeuvre, created in less than a decade, offers a compelling window into the transition from Impressionism and Post-Impressionism towards the nascent stirrings of Fauvism and modern art. His keen observational skills, coupled with a profound empathy for his subjects, allowed him to capture the essence of Parisian life and the intimate moments of human connection with a distinctive sensitivity and an evolving, dynamic style.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Henri-Jacques Édouard Evenepoel was born on October 3, 1872, in Nice, France, to Belgian parents, Edmond Evenepoel and Mélanie Hannon. Though born on French soil, his upbringing and cultural identity were firmly rooted in Belgium. His early life was marked by personal loss; his mother passed away when he was just two years old, a circumstance that perhaps fostered a deep sensitivity evident in his later portraiture. Raised in Brussels, he was surrounded by a family that, while not directly artistic, provided a supportive environment. His cousin, Louise De Mey-van Mattemburgh, and her children, particularly his godson Charles, would later become frequent and beloved subjects of his paintings.

Evenepoel's formal artistic training commenced in Brussels. From 1889 to 1890, he studied drawing at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, a traditional institution that would have provided him with a solid grounding in academic principles. He continued his studies there, likely until 1892, absorbing the prevailing artistic currents in the Belgian capital, which at the time included Realism, Impressionism, and the burgeoning Symbolist movement, with artists like James Ensor and Fernand Khnopff making significant waves. This foundational period in Brussels was crucial in shaping his technical skills and initial artistic outlook before he sought the more radical artistic environment of Paris.

Parisian Sojourn and the Atelier of Gustave Moreau

In 1892, at the age of twenty, Evenepoel made the pivotal decision to move to Paris, the undisputed center of the avant-garde. This move was essential for any ambitious young artist seeking to immerse themselves in the latest artistic developments. He enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, where he entered the studio of Gustave Moreau. Moreau was an unconventional and highly respected teacher, known for his Symbolist paintings and, more importantly, for encouraging his students to develop their individual artistic personalities rather than imposing a rigid style.

Moreau's atelier was a crucible of talent. It was here that Evenepoel encountered a remarkable group of young artists who would go on to become leading figures of modern art. His fellow students included Henri Matisse, Georges Rouault, Albert Marquet, Charles Camoin, and Simon Bussy. The environment was one of fervent discussion, mutual influence, and artistic exploration. Evenepoel formed close friendships within this circle, and the intellectual and artistic stimulation was undoubtedly immense. While Moreau's own work was steeped in mythological and biblical themes, his pedagogy fostered a spirit of independence that allowed artists like Matisse and Evenepoel to explore contemporary life and bold new uses of color.

Evenepoel's early Parisian works began to show the influence of his surroundings and his peers. He was a keen observer of Parisian life, drawn to its streets, its people, and its unique atmosphere. He absorbed the lessons of Impressionism, particularly from artists like Edgar Degas and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, whose depictions of modern urban life, theatrical scenes, and candid portrayals of individuals resonated with Evenepoel's own interests. The influence of Manet, with his bold compositions and contemporary subject matter, can also be discerned.

Development of a Personal Style: Observation and Intimacy

Evenepoel's artistic style evolved rapidly during his years in Paris. While he absorbed influences from Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, he forged a distinctly personal approach. His work is characterized by a strong sense of realism, but it is a realism imbued with psychological depth and a tender humanism. He was particularly adept at portraiture, often painting his family, friends, and especially children. These portraits are remarkable for their lack of sentimentality, instead capturing the unique character and inner life of the sitter with honesty and affection.

His palette, initially somewhat subdued and influenced by the tonal harmonies of artists like James McNeill Whistler or the Belgian Realists, gradually brightened. He began to experiment with more expressive color and bolder compositions. His depictions of Parisian life extended beyond formal portraits to include scenes of everyday life: workers, street scenes, and public spaces. He was interested in the social fabric of the city, from its bustling boulevards to its more humble quarters.

A significant aspect of Evenepoel's practice was his use of photography. In 1897, he acquired a Kodak camera and became an avid photographer. He used photography not merely as a documentary tool but as an aid to his painting, capturing fleeting moments, compositions, and details of Parisian life that he could later translate onto canvas. This engagement with a modern technological medium demonstrates his forward-thinking approach and his willingness to embrace new tools in his artistic exploration. His photographs, many of which survive, offer fascinating insights into his visual interests and working methods.

Key Themes and Subjects in Evenepoel's Art

Evenepoel's subject matter was diverse, yet consistently focused on the human element and the contemporary world around him. His most celebrated works often fall into several key thematic categories.

Portraits of Family and Children:

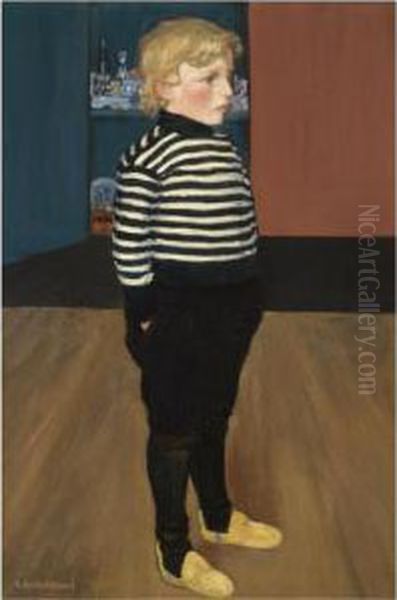

Perhaps his most endearing and well-known works are his portraits of children, particularly those of his cousin Louise's children: Henriette, Sophie, and his godson Charles. Paintings like Charles au jersey rayé (Charles in a Striped Jersey, 1898) are masterpieces of child portraiture. In this work, the young Charles is depicted with a direct gaze, his form rendered with a combination of sensitivity and bold, almost geometric simplification in the striped jersey. The warmth of the colors and the intimate understanding of the child's presence are palpable. These works avoid cloying sweetness, instead conveying a genuine sense of the child's individuality and quiet contemplation. He also painted his father, Edmond, and other family members, capturing familial bonds with a gentle realism.

Parisian Life and Urban Scenes:

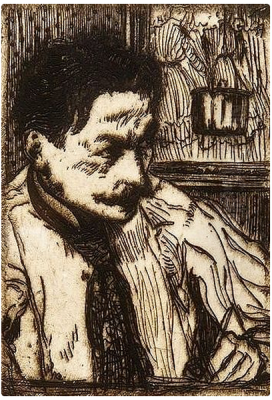

Evenepoel was a chronicler of Parisian life. He painted scenes in cafes, theaters, and public parks, capturing the vibrant, sometimes melancholic, atmosphere of the city. Works like Le Spaniard à Paris (The Spaniard in Paris, 1899), a striking portrait of his friend, the Spanish painter Francisco Iturrino, is a powerful depiction of an artist in the bustling metropolis. The painting conveys a sense of introspection and perhaps the alienation that could be felt even amidst the city's dynamism. Other works depicted the working class, such as Son of the Seine or Return from Work, showing his interest in social realism, a theme also explored by artists like Jean-François Millet or Honoré Daumier in earlier generations, and contemporaneously by artists like Théophile Steinlen.

The Allure of the Exotic: The Algerian Journey

A pivotal period in Evenepoel's artistic development was his trip to Algeria in the winter of 1897-1898. Like Eugène Delacroix and later Matisse and Marquet, Evenepoel was drawn to the light and color of North Africa. This journey had a profound impact on his palette, which became noticeably brighter and more vibrant. In Algeria, he painted market scenes, local figures, and landscapes, experimenting with bolder color contrasts and a more expressive application of paint. Works such as Marché d'oranges à Blida (Orange Market in Blida) and La danse, Algérie (The Dance, Algeria) showcase this shift. The intense North African light encouraged him to explore the full potential of color, pushing his work towards what would soon be recognized as Fauvism. This experience in Algeria undoubtedly prefigured the coloristic explosions that characterized the work of Matisse, André Derain, and Maurice de Vlaminck a few years later.

Artistic Connections and Influences

Evenepoel was not an isolated artist. His time in Moreau's studio placed him at the center of a dynamic group of emerging talents. His relationship with Henri Matisse was particularly significant. They were contemporaries and friends, sharing a period of artistic exploration. While their paths would eventually diverge, the mutual respect and influence during their formative years are evident. Evenepoel's letters often mention Matisse and other colleagues, providing valuable insights into their shared artistic concerns.

Beyond Moreau's circle, Evenepoel was aware of and influenced by a wide range of artists. The legacy of Impressionists like Degas and Monet, and Post-Impressionists such as Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Gauguin, and Vincent van Gogh, was pervasive in Paris at the time. Evenepoel absorbed these influences, adapting them to his own vision. He also had connections with the Nabis group, which included artists like Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, and Maurice Denis. The Nabis' emphasis on decorative composition, subjective color, and intimate domestic scenes may have resonated with Evenepoel's own inclinations, particularly in his interior scenes and portraits.

His work also shows an affinity with contemporary Belgian artists. While based in Paris, he remained connected to the Belgian art scene, exhibiting in Brussels. Artists like Théo van Rysselberghe, a key figure in Belgian Neo-Impressionism, or the Symbolist James Ensor, represented different facets of the rich artistic landscape of his home country. Evenepoel's unique position, straddling the Parisian avant-garde and his Belgian roots, contributed to the distinct character of his art.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Despite his short career, Evenepoel achieved a degree of recognition during his lifetime. He began exhibiting his work regularly. His debut at the prestigious Paris Salon des Artistes Français was in 1894 with a portrait of his cousin, Madame D. (Louise De Mey). He continued to exhibit at the Salon in subsequent years. In 1895, he held his first solo exhibition, a significant milestone for a young artist.

He also participated in exhibitions in Brussels, maintaining his ties with the Belgian art world. He exhibited at the Salons de La Libre Esthétique, a progressive exhibition society that succeeded Les XX and played a crucial role in promoting avant-garde art in Belgium. His work was noted for its sincerity, its skillful execution, and its modern sensibility. Had he lived longer, there is no doubt that his reputation would have grown even more substantially.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

A deeper examination of some of Evenepoel's key works reveals the nuances of his artistic achievements:

Le Spaniard à Paris (The Spaniard in Paris, Francisco Iturrino) (1899): This is arguably one of his most iconic paintings. The portrait of his friend, the painter Francisco Iturrino, is a powerful psychological study. Iturrino is depicted in a café, a quintessential Parisian setting, yet he appears somewhat isolated and introspective. The strong contrasts of light and shadow, the bold composition, and the expressive rendering of the figure make this a compelling image of an artist navigating the complexities of modern urban life. The rich, dark tones are punctuated by the vibrant red of the banquette, showcasing Evenepoel's sophisticated color sense.

Charles au jersey rayé (Charles in a Striped Jersey) (1898): This tender portrait of his godson Charles is a testament to Evenepoel's skill in capturing the innocence and quiet gravity of childhood. The boy's direct gaze engages the viewer, while the boldly striped jersey, rendered with broad, flat areas of color, anticipates Fauvist aesthetics. The warmth of the palette and the intimate composition create a sense of deep affection. This work is now a treasured part of the collection at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels.

L'Homme en rouge (Portrait of Paul Baignères) (1894): An early success, this portrait of the writer and dandy Paul Baignères (who introduced Evenepoel to Marcel Proust) demonstrates Evenepoel's skill in capturing character. The elegant pose and the sophisticated handling of color and texture reflect the influence of Whistler and Sargent, yet with Evenepoel's emerging personal touch.

La Neige (The Snow): This work, depicting a snow-covered Parisian scene, showcases Evenepoel's ability to capture atmospheric effects. The subtle gradations of white and grey, punctuated by darker accents, create a poetic and evocative image of the city transformed by winter.

Marché d'oranges à Blida (Orange Market in Blida) (1898): Painted during his Algerian sojourn, this work is a riot of color and light. The vibrant oranges, the bright sunlight, and the lively depiction of the market scene demonstrate the profound impact of North Africa on his palette. It is a clear precursor to the Fauvist explosion of color.

Fête Foraine au Boulevard de Clichy (Fairground at the Boulevard de Clichy) (c. 1892-1897): This painting captures the lively, somewhat chaotic atmosphere of a Parisian fair. The depiction of crowds, lights, and movement shows his interest in capturing the dynamism of urban entertainment, a theme also explored by artists like Seurat and Toulouse-Lautrec. Some sources suggest he even experimented with Pointillist techniques in works like this, showing his willingness to explore different stylistic avenues.

Premature Death and Lasting Legacy

Tragically, Henri-Jacques Evenepoel's promising career was cut short. In December 1899, while back in Paris after his military service considerations, he contracted typhoid fever. He passed away on December 27, 1899, at the young age of 27. His death was a profound loss to the art world, silencing a voice that was just beginning to reach its full potential. One can only speculate on the direction his art might have taken had he lived to participate fully in the Fauvist movement he helped to presage, or the subsequent developments of Cubism and beyond.

Despite his brief career, Evenepoel left behind a significant body of work – paintings, drawings, and photographs – that attest to his remarkable talent. His art is characterized by its honesty, its sensitivity, and its keen observation of the world around him. He successfully bridged the gap between the academic tradition and the emerging avant-garde, creating a style that was both modern and deeply personal.

His influence can be seen in the development of early 20th-century art, particularly in Belgium and France. His bold use of color, especially after his trip to Algeria, anticipated the Fauvist movement. Artists like Matisse, who knew him well, would go on to champion the expressive power of color in ways that Evenepoel had begun to explore. In Belgium, he is regarded as one of the most important painters of his generation, a key figure in the transition towards modernism.

His works are held in major museum collections, primarily in Belgium (such as the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels and the Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent) and France, but also internationally. Retrospectives of his work continue to draw attention to his unique contribution to art history.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Henri-Jacques Evenepoel's life was tragically brief, but his artistic legacy endures. In less than a decade of mature artistic production, he created a body of work that is remarkable for its quality, its emotional depth, and its stylistic innovation. As a student of Gustave Moreau, a contemporary of Matisse and Rouault, and an admirer of Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec, he was at the crossroads of major artistic shifts at the end of the 19th century.

His portraits, particularly of children, are imbued with a rare tenderness and psychological insight. His depictions of Parisian life capture the vibrant, multifaceted character of the fin-de-siècle metropolis. His Algerian paintings reveal a burgeoning passion for color that placed him on the cusp of Fauvism. Evenepoel was more than just a talented painter; he was an artist of profound sensitivity and keen intelligence, whose work continues to resonate with viewers today. He remains a testament to the power of a singular artistic vision, however short its earthly span. His contribution to Belgian art and to the broader narrative of European modernism is undeniable, securing his place as a luminous figure in the rich tapestry of art history.