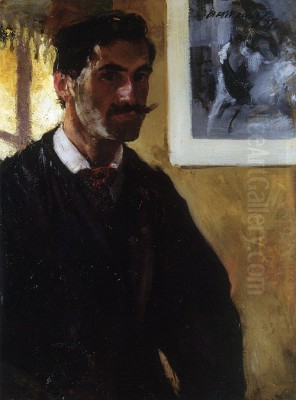

Alfred Henry Maurer (1868-1932) stands as a pivotal yet often tragically overlooked figure in the narrative of American modernism. His life encompassed a dramatic artistic evolution, beginning in the accepted academic traditions of the late 19th century and boldly venturing into the heart of European avant-garde movements like Fauvism and Cubism. Born into an artistic family in New York City, Maurer's path led him to the vibrant art scene of Paris, where his transformation unfolded. Despite early accolades, his embrace of modernism brought personal and professional challenges, culminating in a life cut short by despair. Yet, his contributions as one of America's earliest and most dedicated modernists remain undeniable, paving the way for subsequent generations of artists.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Alfred H. Maurer was born in New York City on April 21, 1868. His father, Louis Maurer, was a German immigrant, a successful commercial artist, renowned lithographer, and painter known for his detailed genre scenes, particularly those published by Currier & Ives. Growing up in this environment, the young Alfred was exposed to art from an early age. However, his path into the art world was not immediate. At the age of sixteen, he left school to work at his father's lithographic firm, Maurer & Heppenheimer.

While gaining practical experience in the commercial art world, Alfred's desire for fine art training grew. He eventually pursued formal studies, enrolling at the National Academy of Design in New York. During this period, he sought out instruction from prominent figures in the American art scene. He studied with the influential painter and teacher William Merritt Chase, known for his bravura brushwork and sophisticated portraits, absorbing the tenets of American Impressionism and refined realism prevalent at the time. Some accounts also mention study with the sculptor John Quincy Adams Ward, though Chase's influence seems more pronounced on his early painting style.

Maurer's early work reflected this academic training and the prevailing tastes. His paintings were characterized by tonal subtlety, competent draughtsmanship, and an adherence to realistic representation, often depicting elegant figures in dimly lit interiors. This initial phase showed promise within the established art world, hinting at a successful conventional career.

Parisian Awakening

The lure of Paris, the undisputed center of the art world at the turn of the century, proved irresistible for the ambitious young Maurer. In 1897, at the age of 29, he sailed for Europe, seeking broader artistic horizons and direct exposure to the latest developments. Upon arrival, he briefly enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, a common destination for foreign art students. However, like many artists seeking a less structured environment, he found the academic routine stifling and soon left.

Maurer preferred the independence of self-directed study, immersing himself in the city's museums, galleries, and the vibrant café culture where artists and intellectuals congregated. He diligently studied the works of Old Masters at the Louvre but was equally drawn to contemporary art. His initial years in Paris saw him refining a style influenced by James McNeill Whistler, characterized by elegant compositions, muted color palettes, and an emphasis on atmospheric effects. This sophisticated, tonalist approach brought him early recognition.

This early Parisian period was marked by conventional success. Maurer submitted works to various salons and exhibitions, gradually building a reputation as a talented expatriate artist working within accepted aesthetic boundaries. His technical skill was evident, and his paintings from this time were well-received by critics who appreciated their refinement and connection to established traditions.

Immersion in the Avant-Garde

Maurer's comfortable trajectory within traditional art circles took a decisive turn around 1904-1905. Paris was a crucible of artistic innovation, and Maurer found himself at the epicenter of radical new ideas. He became part of an influential circle of American expatriates, most notably the writer and art collector Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo Stein. Their famous salon at 27 rue de Fleurus became a meeting place for the avant-garde, exposing Maurer directly to the revolutionary works of artists they championed.

Through the Steins and his own explorations, Maurer encountered the shocking colors and bold forms of Fauvism, spearheaded by Henri Matisse. He also witnessed the nascent stages of Cubism being developed by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. These encounters fundamentally altered his artistic vision. He formed friendships with fellow American artists exploring modernism, including Arthur Dove, who would become a lifelong friend and a key figure in American abstract art. Maurer is credited with introducing Dove to the works of Matisse and other modernists, significantly impacting Dove's own artistic development.

Maurer began exhibiting with the more progressive factions in Paris. He showed work at the Salon d'Automne, a key venue for Fauvist artists, starting in 1905. This immersion in the Parisian avant-garde milieu provided not only inspiration but also intellectual validation for moving beyond the constraints of his earlier style. He absorbed the lessons of Paul Cézanne's structural approach to composition, Paul Gauguin's symbolic use of color, and Matisse's radical liberation of color from purely descriptive purposes.

Early Acclaim and a Fateful Turn

Before his complete conversion to modernism, Maurer achieved significant recognition for his earlier, more traditional work. His painting An Arrangement, a Whistlerian study of a woman in an interior, won the prestigious Gold Medal (first prize) at the Carnegie International Exhibition in Pittsburgh in 1901. This award brought him considerable acclaim back in the United States and seemed to promise a bright future as a leading academic painter. He continued to garner awards, including medals at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo (1901), the St. Louis Universal Exposition (1904), and international exhibitions in Liège (1905) and Munich (1905).

However, even as these accolades accumulated, Maurer's artistic direction was shifting dramatically. His exposure to Fauvism around 1904 led him to abandon the muted palettes and subtle tonalism of his award-winning style. He began experimenting with vibrant, non-naturalistic colors, bold outlines, and simplified forms. This radical departure perplexed and alienated many who had admired his earlier work.

Crucially, this stylistic shift created a deep rift with his father, Louis Maurer. The elder Maurer, a successful traditional artist, could not comprehend or accept his son's embrace of modernism, viewing it as a betrayal of artistic principles and a squandering of talent. This paternal disapproval became a source of ongoing conflict and personal anguish for Alfred, casting a shadow over his career and likely contributing to his later emotional struggles. The break was profound; the artist who had won international acclaim was now setting himself on a path that would lead to critical misunderstanding and commercial difficulty.

The Fauvist Experiment

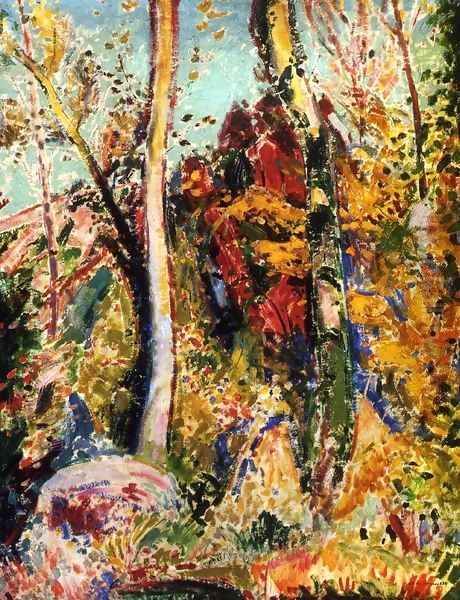

Around 1906-1907, Maurer fully embraced the principles of Fauvism. Inspired directly by the works of Henri Matisse, André Derain, and Maurice de Vlaminck, which he saw at the Salon d'Automne and possibly in the studios of fellow artists, Maurer began producing landscapes and figure studies characterized by startlingly bright, arbitrary color and energetic, expressive brushwork. His goal shifted from realistic depiction to conveying emotion and achieving decorative harmony through color and line.

His Fauvist landscapes, often painted in the French countryside, employed patches of intense blues, greens, reds, and yellows, applied with a directness that prioritized visual impact over topographical accuracy. Figures were simplified, outlined boldly, and rendered with flat planes of color. This period marked a definitive break from the illusionistic space and subtle modeling of his earlier work. He was exploring the autonomous power of color to structure a painting and evoke feeling.

While Maurer never achieved the same level of recognition as the leading French Fauves, his work from this period is significant as among the earliest and most committed explorations of Fauvism by an American artist. He absorbed the core tenets of the movement – the liberation of color, the simplification of form, the emphasis on subjective experience – and adapted them to his own sensibility. These Fauvist works, though perhaps less known than his later Cubist experiments, represent a crucial stage in his development and his commitment to the modernist cause.

Deconstructing Form: Maurer and Cubism

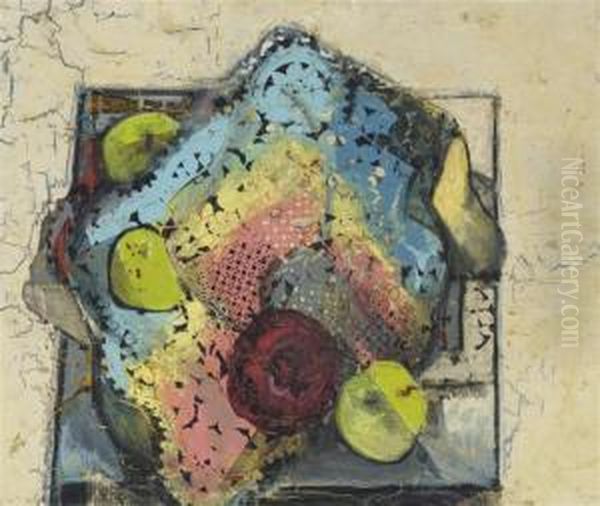

Following his engagement with Fauvism, Maurer's restless artistic spirit led him to explore the complexities of Cubism. While still retaining a Fauvist intensity of color in some works, he began to incorporate the fragmented forms, geometric structures, and shifting perspectives characteristic of the style pioneered by Picasso and Braque. His Cubist works, primarily still lifes and portraits, developed from around 1910 onwards and continued, evolving, through much of his later career.

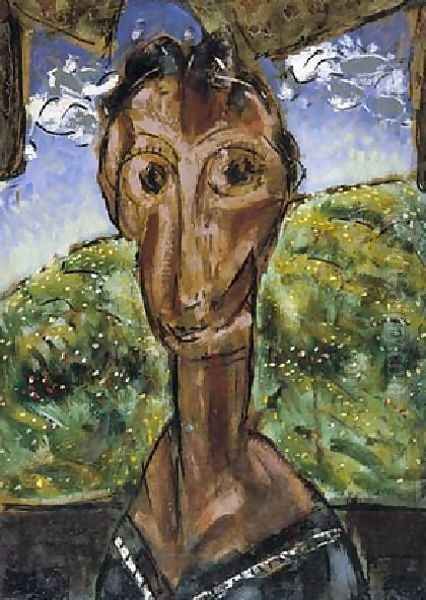

Maurer's approach to Cubism was distinct. Unlike the often monochromatic, highly analytical works of Picasso and Braque's early Cubist phase, Maurer frequently employed a richer, more varied palette, sometimes retaining echoes of his Fauvist sensibility. His compositions often featured recognizable subjects – typically female heads or arrangements of objects on a tabletop – subjected to a process of faceting and spatial reorganization. He fractured planes and presented multiple viewpoints simultaneously, challenging traditional notions of representation.

Works like Two Heads (c. 1928-1930) exemplify his mature Cubist style, demonstrating a sophisticated understanding of the style's formal language combined with a personal, expressive quality. He explored the interplay of line, plane, and color to create dynamic compositions that hovered between representation and abstraction. While perhaps not as rigorously analytical as some European Cubism, Maurer's work in this vein is considered a significant contribution to the development of Cubism in America, showcasing his ability to synthesize European innovations into a unique artistic statement.

Bridging Continents: New York and the Modernist Dawn

Although Maurer spent a significant portion of his formative modernist years in Paris (nearly 17 years), he maintained connections with the burgeoning modern art scene in New York. His work was included in the groundbreaking International Exhibition of Modern Art, better known as the Armory Show, held in New York City in 1913. This landmark exhibition introduced large American audiences to European avant-garde art, featuring works by artists like Matisse, Picasso, Duchamp, and Kandinsky alongside progressive American artists. Maurer's inclusion signaled his position within the American modernist vanguard.

Maurer also became associated with the influential photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz, a key promoter of modern art in America. Stieglitz exhibited Maurer's work at his gallery "291" (originally the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession) as early as 1909, in a four-person show that also included John Marin. Stieglitz gave Maurer his first solo show in the United States in 1913. This connection placed Maurer within the orbit of other important early American modernists championed by Stieglitz, such as Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove, Georgia O'Keeffe, and Max Weber.

With the outbreak of World War I in Europe, Maurer returned permanently to New York City in 1914. He arrived back in an America that was slowly beginning to grapple with the implications of modernism, partly thanks to the impact of the Armory Show. However, the general artistic climate remained largely conservative, and Maurer would find the reception of his advanced art challenging.

Navigating the American Art World

Upon his return to the United States, Alfred Maurer faced significant difficulties in gaining acceptance and patronage for his modernist work. The American art market was still largely dominated by academic realism and American Scene painting. While a small circle of collectors and critics associated with Stieglitz and other progressive venues appreciated his work, broader recognition and financial success eluded him. The bold colors of his Fauvist-inspired works and the fragmented forms of his Cubist paintings were often met with incomprehension or hostility.

Despite these challenges, Maurer continued to paint prolifically and participate actively in the New York art world. He became involved with the Society of Independent Artists, an organization founded in 1916 on the principle of "no jury, no prizes," aiming to provide an open venue for avant-garde artists. Maurer exhibited regularly with the Society and served as its director from 1919 until his death, demonstrating his commitment to supporting fellow modernists.

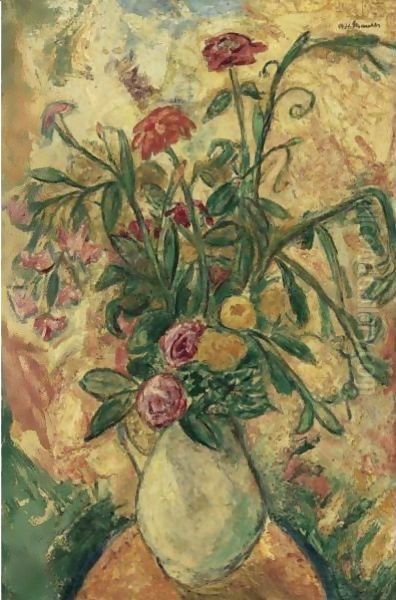

His later work continued to explore Fauvist and Cubist idioms, often focusing on portraits, particularly elongated, melancholic female heads, and vibrant still life compositions like Vase of Flowers. These works often possess a heightened emotional intensity, perhaps reflecting his personal struggles. He experimented with different techniques and materials, always pushing his artistic boundaries even in the face of limited public appreciation. He lived frugally, often supported by the forward-thinking dealer Erhard Weyhe, but financial insecurity remained a constant pressure.

A Generational Divide: The Conflict with Louis Maurer

One of the most persistent and painful aspects of Alfred Maurer's life was the unresolved conflict with his father, Louis Maurer. Louis, who lived to be nearly 100 years old (dying in 1932, the same year as Alfred), represented the epitome of 19th-century artistic success through traditional skill and commercial acumen. He had witnessed Alfred's early triumphs, like the Carnegie Gold Medal, with pride, anticipating a continuation of this conventional path.

Alfred's radical embrace of European modernism after 1904 was therefore deeply troubling to Louis. He viewed Fauvism and Cubism not as legitimate artistic explorations but as aberrations, a rejection of skill and beauty. This fundamental disagreement created a chasm between father and son. Reports suggest Louis openly criticized Alfred's work and withdrew his support, both emotional and potentially financial.

This paternal rejection weighed heavily on Alfred. He lived in his father's house upon returning to New York, creating a situation fraught with tension. The constant presence of his father's disapproval, coupled with the lack of wider recognition for the art he believed in, undoubtedly contributed to Maurer's sense of isolation and failure. This complex father-son dynamic, rooted in opposing artistic ideologies across a generational divide, forms a poignant backdrop to Maurer's later life and struggles.

Isolation and Final Works

In the later years of his life, particularly during the late 1920s and early 1930s, Alfred Maurer seemed to withdraw increasingly into himself. While he continued to paint with intensity, his subjects often took on a more somber, introspective quality. His series of female heads from this period are particularly notable. Often depicted with elongated necks, large, haunting eyes, and melancholic expressions, these works convey a profound sense of sadness and psychological depth. Rendered with a blend of Cubist faceting and Fauvist color, they are among his most personal and emotionally resonant creations.

His financial situation remained precarious, and critical recognition, while present in avant-garde circles, did not translate into widespread acclaim or security. The Great Depression, beginning in 1929, further darkened the prospects for artists, especially those working outside the mainstream. Maurer felt increasingly out of step with the prevailing trends in American art, which were shifting towards Regionalism and Social Realism, styles often perceived as more accessible and nationally relevant than his European-inflected modernism.

Friends noted his growing despondency and isolation. The vibrant connections of his Paris years seemed distant, and the supportive community he found in the Society of Independent Artists could not fully alleviate his personal struggles. His art, while continuing to evolve, seemed to reflect this inner turmoil, exploring themes of introspection and vulnerability.

A Tragic Conclusion

The final chapter of Alfred Maurer's life unfolded with tragic swiftness in 1932. His father, Louis Maurer, died on July 19th of that year, just short of his 100th birthday. Despite their long-standing conflicts, the loss of his father appears to have deeply affected Alfred. Only a few weeks later, on August 4, 1932, Alfred Henry Maurer took his own life in the family home where he lived. He was 64 years old.

His suicide stunned the New York art world. While his struggles were known to some, the finality of his act underscored the immense pressures he had faced – the lack of recognition, the financial hardship, the complex family dynamics, and likely a long battle with depression. His death highlighted the difficulties faced by pioneering modernists in America, artists who pursued their vision against prevailing tastes and often at great personal cost.

Maurer left behind a substantial body of work, much of it stored in his studio, representing the full arc of his artistic journey from academic realism to radical modernism. His tragic end seemed, for a time, to overshadow his artistic achievements.

Legacy of a Pioneer

In the decades following his death, Alfred Henry Maurer's reputation underwent a significant re-evaluation. While underappreciated during much of his lifetime, art historians and curators began to recognize the importance of his role as one of America's first and most dedicated modernists. His willingness to engage deeply with European avant-garde movements like Fauvism and Cubism, long before they were widely accepted in the United States, marked him as a true pioneer.

His influence on fellow artists, such as Arthur Dove, and his participation in key institutions and exhibitions like the Armory Show, the Society of Independent Artists, and Stieglitz's "291" gallery, place him firmly within the narrative of American modern art's development. He served as a crucial conduit, absorbing the radical ideas of Paris and translating them into an American context, thereby helping to shape the direction of art in his home country. His work demonstrated that American artists could engage with international modernism on their own terms.

Today, Maurer's paintings are held in major museum collections across the United States, including the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Phillips Collection, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Exhibitions and scholarly publications have shed light on the breadth and depth of his oeuvre, revealing an artist of considerable talent, sensitivity, and courage. His journey from a prize-winning realist to a struggling avant-gardist reflects the turbulent transition of art in the early 20th century. His legacy is that of an artist who remained true to his evolving vision, contributing significantly to the foundations of American modernism despite profound personal adversity. His name belongs alongside other key figures who forged a modern artistic identity for America, including Marsden Hartley, John Marin, Max Weber, Charles Demuth, Stanton Macdonald-Wright, and Morgan Russell.

Conclusion

Alfred Henry Maurer's life and career present a compelling, complex, and ultimately tragic story of artistic transformation and struggle. He began as a highly promising painter within traditional bounds, achieving international recognition early on. Yet, driven by artistic conviction, he embraced the radical innovations of European modernism, becoming a key figure in introducing Fauvism and Cubism to America. This path, however, led to alienation from his father, critical misunderstanding, and financial hardship. Despite these obstacles, he produced a rich and varied body of work that charts a unique course through the major artistic developments of his time. Though his life ended in despair, Alfred Henry Maurer's legacy endures as a testament to his pioneering spirit and his significant, hard-won contribution to the history of American art.