Dezső Czigány stands as a pivotal yet tragic figure in the annals of Hungarian art. Born in Budapest in 1883, his life, though cut short in 1937, was one of intense artistic exploration, significant contribution to the Hungarian avant-garde, and ultimately, profound personal tragedy. As a founding member of the influential group "The Eight" (Nyolcak), Czigány played a crucial role in steering Hungarian art away from academic conservatism and towards the burgeoning modernist movements sweeping across Europe. His work, characterized by rigorous composition, expressive force, and a deep engagement with his subjects, reflects a complex artistic personality shaped by diverse influences and a keen observational eye. This exploration will delve into his life, his artistic development, his seminal role within The Eight, his key works, his interactions with contemporaries, and the lasting, albeit somber, legacy he left behind.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Dezső Czigány's journey into the world of art began in his native Budapest, a city vibrant with cultural and intellectual ferment at the turn of the 20th century. He initially enrolled at the Nagykárolyi School of Art in Budapest, completing his studies there between 1901 and 1903. This foundational period would have exposed him to the prevailing academic traditions, but also to the nascent stirrings of change within Hungarian artistic circles. Like many ambitious young artists of his generation, Czigány recognized the need to seek training and inspiration beyond national borders, particularly in the major art centers of Europe.

His quest led him first to Munich, a city that, alongside Paris, was a crucible for artistic innovation. In Munich, he studied at the private school of Simon Hollósy. Hollósy was a highly respected Hungarian painter and an influential teacher, known for his plein-air painting and his role in the Nagybánya artists' colony, which had already begun to introduce more modern, naturalistic, and impressionistic tendencies into Hungarian art, moving away from the stricter dictates of the Munich Academy. Studying with Hollósy would have provided Czigány with a solid grounding in drawing and painting, while also exposing him to a more liberal artistic environment than traditional academies.

However, it was Paris that would prove to be the most transformative experience for Czigány, as it was for so many artists of his era. He continued his studies in the French capital, immersing himself in its unparalleled artistic dynamism. Paris was the undisputed epicenter of the avant-garde, where movements like Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and the early stages of Cubism were radically reshaping artistic expression. It was here that Czigány encountered firsthand the works of masters who would profoundly influence his artistic trajectory.

The Parisian Crucible: Influences and Development

In Paris, Czigány absorbed a multitude of influences. He was particularly drawn to the work of Paul Cézanne, whose emphasis on underlying geometric structure, the solidity of form, and the construction of space through color planes resonated deeply with Czigány's own developing artistic temperament. Cézanne's methodical approach to still life and landscape, his departure from traditional perspective, and his famous dictum to "treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone," offered a new way of seeing and representing the world. This influence would become evident in Czigány's own carefully constructed still lifes and portraits, which often display a Cézannesque concern for volume and structural integrity.

Another significant influence was Paul Gauguin. Gauguin's bold use of color, his flattened perspectives, his interest in "primitive" art, and his Symbolist leanings provided a counterpoint to Cézanne's structural concerns. Gauguin's expressive color and simplified forms, often imbued with emotional or spiritual content, likely appealed to Czigány's desire to move beyond mere representation. The impact of Fauvism, with its explosive, non-naturalistic use of color championed by artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain, was also palpable in Paris at this time. While Czigány might not have adopted the full exuberance of Fauvist color, its liberating effect on the palette was an undeniable part of the Parisian artistic atmosphere he breathed.

Czigány's time in Paris was not solely about absorbing influences; it was also about forging his own artistic identity. He developed a style characterized by a certain austerity, a rigorous approach to composition, and a powerful, often somber, expressiveness. His palette, while capable of richness, often leaned towards controlled harmonies and strong contrasts, reflecting a thoughtful and analytical mind. He began to focus on genres that would remain central to his oeuvre: still life, portraiture, and particularly, self-portraiture, which he used as a vehicle for intense introspection.

The Eight (Nyolcak): Forging a Hungarian Avant-Garde

Upon his return to Hungary, Czigány, along with a group of like-minded artists, became a driving force in the formation of "The Eight" (Nyolcak). This group, which officially debuted with an exhibition titled "New Pictures" at the Könyves Kálmán Salon in Budapest in 1909 (though they formally named themselves The Eight for their second exhibition in 1911), was a seminal moment in Hungarian modernism. The founding members, besides Czigány, were Róbert Berény, Béla Czobel, Károly Kernstok, Ödön Márffy, Dezső Orbán, Bertalan Pór, and Lajos Tihany. Most of these artists had also spent time studying and working in Paris, and they shared a common goal: to introduce the latest European artistic trends, particularly those emanating from France, into the Hungarian art scene.

The Eight sought to break decisively with the academicism and naturalism that still dominated much of Hungarian art. They championed artistic freedom, individual expression, and the principles of Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and early Cubism. Their exhibitions were often met with controversy and criticism from conservative quarters, but they also attracted significant attention and helped to foster a climate of artistic debate and innovation. Károly Kernstok was often seen as the intellectual leader of the group, but each member brought a distinct artistic personality to the collective.

Czigány was a vital member of this collective. His work, with its structural rigor derived from Cézanne and its expressive intensity, aligned perfectly with the group's aims. The Eight were not a homogenous group stylistically, but they were united by their progressive outlook and their desire to create a modern Hungarian art that was both internationally aware and rooted in its own cultural context. They emphasized the constructive and expressive power of art, moving beyond the impressionistic concern for fleeting moments of light and atmosphere. Their subjects often included portraits, nudes, landscapes, and compositions with symbolic or social undertones. The group also had connections with other avant-garde figures in Hungarian culture, including the poet Endre Ady and the composer Béla Bartók, reflecting a broader modernist ferment in the country.

Czigány's Artistic Style: Structure, Expression, and Subject Matter

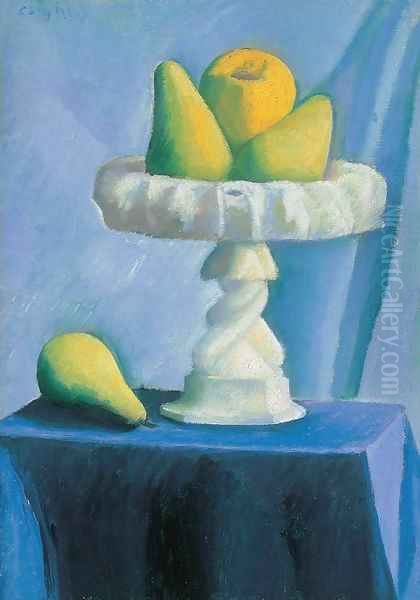

Dezső Czigány's artistic style is often described as severe, disciplined, and powerfully expressive. His primary genres were still life and portraiture, including numerous self-portraits that offer a glimpse into his intense and perhaps troubled psyche. In his still lifes, Czigány demonstrated a profound understanding of Cézanne's principles. He meticulously arranged objects – typically fruits, bottles, and vessels – exploring their volumetric qualities and their relationships within the pictorial space. His compositions are often compact and densely structured, with a focus on form and a somewhat subdued but rich color palette. Works like his "Still Life with Apples and Wine Bottle" (c. 1910) or "Still Life with Pears" (c. 1912) showcase this Cézannist approach, where objects are rendered with a palpable sense of weight and presence, and color is used to build form rather than merely describe surfaces.

His portraits and self-portraits are particularly compelling. They reveal a search for psychological depth and an unflinching honesty. Czigány's self-portraits, painted throughout his career, are notable for their intensity and introspection. They often feature a direct, searching gaze, and a modeling of the face that emphasizes its structural planes, again recalling Cézanne but imbued with a more personal, sometimes melancholic, expressiveness. He painted portraits of friends and cultural figures, capturing not just a likeness but also a sense of the sitter's inner life. The influence of Expressionism, with its emphasis on subjective feeling and emotional impact, can also be felt in the intensity of these works.

Beyond the direct influence of French Post-Impressionism and Fauvism, some art historians have noted a subtle assimilation of Baroque principles in Czigány's work, particularly in his use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to create dramatic effects and enhance the plasticity of forms. This might seem a surprising combination, but it speaks to Czigány's ability to synthesize diverse influences into a personal style. His engagement with the art of the past, including masters like Rembrandt van Rijn, known for his dramatic use of light, could have informed this aspect of his work.

A significant, though perhaps less dominant, theme in Czigány's oeuvre was his depiction of social realities, particularly figures from the margins of society. His painting "The Beggar" (c. 1900-1902), an earlier work, already shows an interest in portraying the disenfranchised with a somber palette and a sense of empathy. This concern for social themes, while not as central as in the work of some of his contemporaries, adds another layer to his artistic identity, suggesting an awareness of the social issues of his time.

Representative Works: A Closer Look

While many of Czigány's works contribute to our understanding of his art, a few stand out or are frequently cited. His "Csendélet" (Still Life) from 1925, mentioned in the provided information as depicting a Parisian scene, would be a later work, suggesting his continued connection to or reflection on his time in Paris. Such a piece would likely demonstrate his mature style, blending structural concerns with a refined sense of color and composition, perhaps imbued with the atmosphere of the city that had been so crucial to his development. Without a specific image, one can surmise it would exhibit the characteristic Czigány traits: thoughtful arrangement, solid forms, and an expressive, if controlled, palette.

His numerous self-portraits are collectively a significant body of work. For instance, a "Self-Portrait with Hat" (various versions exist, e.g., around 1910-1912) often shows him confronting the viewer directly, his features rendered with a combination of structural solidity and psychological intensity. These works are not merely exercises in likeness but profound explorations of self, reflecting the artist's inner world. The handling of paint is often deliberate and constructive, building up the forms of the face and head with a sense of gravity.

His still lifes, such as "Still Life with Fruit Bowl and Jug" (c. 1910s), are exemplary of his engagement with Cézanne. The fruits are not just depicted but are rendered as solid, almost sculptural forms. The interplay of shapes, colors, and the subtle distortions of perspective create a dynamic yet balanced composition. The colors, while often earthy or muted, possess a deep resonance. These works are testaments to his belief in the intellectual rigor of painting, where the arrangement of forms and colors creates its own reality.

Interactions with Contemporaries and Cultural Milieu

Czigány's artistic life was deeply intertwined with his contemporaries, primarily through his involvement with The Eight. The group provided a platform for shared ideals and mutual support, even if their individual styles diverged over time. Róbert Berény, for example, was known for his psychologically charged portraits and his engagement with psychoanalysis. Lajos Tihany developed a powerful, expressionistic style, often with bold colors and dynamic forms. Béla Czobel was closely associated with the Fauvists in Paris and brought a vibrant colorism to Hungarian art. Károly Kernstok, the group's intellectual leader, explored monumental compositions and themes of human strength and vitality. Ödön Márffy's work evolved from Fauvist influences towards a more lyrical and decorative style. Dezső Orbán was known for his landscapes and still lifes, later becoming an influential teacher in Australia. Bertalan Pór created powerful, often symbolic, figure compositions. The interactions, debates, and shared exhibitions among these artists were crucial for the development of Hungarian modernism.

Beyond The Eight, Czigány was part of a broader cultural avant-garde in Budapest. His connections with figures like the poet Endre Ady, whose revolutionary poetry mirrored the artistic aspirations of The Eight, and the composer Béla Bartók, who was similarly forging a new Hungarian musical language by drawing on folk traditions and modernist innovations, highlight the interdisciplinary nature of the modernist movement. These artists and intellectuals often frequented the same cafes and salons, sharing ideas and shaping the cultural landscape of early 20th-century Hungary.

Czigány also maintained connections with the preceding generation of Hungarian innovators, such as József Rippl-Rónai, who had been a member of the Nabis in Paris and introduced Post-Impressionist ideas to Hungary earlier. He would also have been aware of the artists associated with the Nagybánya school, such as its founder Simon Hollósy (his former teacher) and Károly Ferenczy, who, while perhaps more impressionistic or naturalistic, were instrumental in modernizing Hungarian art. Adolf Fényes, another prominent Nagybánya artist, also contributed to this evolving landscape. Czigány's work, therefore, can be seen as building upon these earlier efforts while pushing further into the territory of European modernism. His years in Paris also meant he was aware of international figures beyond his direct influences, including Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, whose Cubist revolution was unfolding during Czigány's formative period.

Later Years and Tragic End

After the initial impact of The Eight, Czigány continued to paint and exhibit. He spent a number of years living in Paris, maintaining his connections with the international art world. His style, while retaining its core characteristics of structural integrity and expressive depth, continued to evolve. However, his later life was overshadowed by increasing personal difficulties.

The provided information confirms the tragic end to Czigány's life. In 1937, reportedly suffering from a severe mental breakdown, Dezső Czigány killed his family and then committed suicide. This horrific event cast a dark shadow over his life and career, and it inevitably colors how his work is perceived. It is a stark reminder of the often-fragile boundary between intense artistic vision and psychological turmoil, a theme that has unfortunately recurred in the lives of several highly creative individuals throughout art history. This tragic end at the age of 54 cut short a significant artistic voice.

Legacy and Art Historical Evaluation

Despite his tragic end and a career that was perhaps not as prolific or as internationally recognized as some of his contemporaries, Dezső Czigány holds an important place in Hungarian art history. His primary contribution lies in his role as a co-founder and key member of The Eight, a group that irrevocably changed the course of Hungarian art by championing modernism. His commitment to the structural principles of Cézanne, combined with an expressive intensity, provided a powerful example for other artists.

His works, particularly his still lifes and self-portraits, are valued for their artistic quality and their historical significance. They are represented in major Hungarian collections, including the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest. His paintings occasionally appear at auction, and as noted, a work like "Utoszar" (Last Ray of Sun or similar meaning, likely a landscape) fetched a significant price, indicating a continued appreciation for his art in the market.

Critically, Czigány is generally well-regarded for the seriousness and integrity of his artistic vision. If there are "controversies" or critical debates, they might revolve around the perceived "severity" or "lack of lyricism" in some of his works, as one source hinted. However, this can also be interpreted as a strength: his refusal of easy sentimentality in favor of a more rigorous and analytical approach to painting. His focus on form and structure, while perhaps making his work less immediately accessible than that of more overtly colorful or decorative artists, gives it an enduring solidity.

The tragedy of his death inevitably complicates his legacy. It is impossible to separate the artist from his life story entirely, but it is crucial to evaluate his artistic achievements on their own merits. His contribution to the Hungarian avant-garde was substantial, and his best works remain powerful testaments to a dedicated and insightful artistic mind. He helped to bridge the gap between Hungarian artistic traditions and the major currents of European modernism, creating a body of work that, while reflecting international influences, possessed a distinct personal character.

Conclusion: An Enduring, Complex Figure

Dezső Czigány's life was a complex tapestry of artistic ambition, significant achievement, and devastating personal tragedy. As a key figure in The Eight, he helped to usher in a new era of modernism in Hungarian art, championing the formal innovations and expressive freedoms that were transforming European visual culture. His deep engagement with the art of Cézanne, Gauguin, and the Parisian avant-garde, synthesized into a style of rigorous construction and profound psychological insight, produced a compelling body of work, particularly in the genres of still life and self-portraiture.

While the horrific circumstances of his death in 1937 cast a somber light on his biography, his artistic contributions remain undeniable. He was an artist of intense vision and unwavering commitment to his craft. His paintings continue to be studied and appreciated for their formal strength, their expressive depth, and their crucial role in the narrative of Hungarian modernism. Dezső Czigány remains an important, if poignant, figure, whose art speaks to the enduring power of creative expression even in the face of profound personal darkness. His legacy is a testament to the vital, transformative, and sometimes perilous journey of the modern artist.