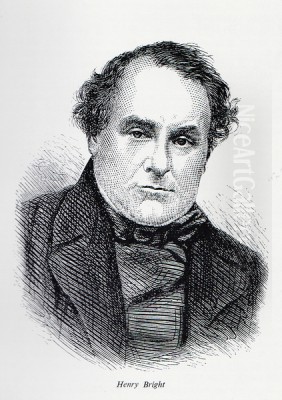

Henry Bright (1810–1873) stands as a significant figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century British landscape painting. Associated with the later phase of the celebrated Norwich School of painters, Bright carved his own distinct path, becoming renowned for his vibrant and technically adept depictions of the natural world. Working proficiently across oil, watercolour, chalk, and pencil, he captured the diverse scenery of the British Isles and continental Europe with an eye for atmospheric effect and picturesque detail. His connections with leading artists of the day, including the titan J.M.W. Turner, and his role as a respected teacher further solidify his place in art history. This exploration delves into the life, work, and enduring legacy of Henry Bright, a painter whose love for the landscape resonated through his prolific output.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Suffolk

Henry Bright was born in Saxmundham, Suffolk, in 1810. His family background was not initially rooted in the arts; his father and grandfather were clockmakers, a trade requiring precision and craftsmanship, but distinct from the world of painting. Following this practical lineage, Bright was first apprenticed to a chemist in his hometown. He continued this path by studying chemistry further in Woodbridge and later in Norwich, where he eventually worked as a dispenser at the Norwich and Norfolk Hospital.

Despite this seemingly settled career in pharmacy, an innate passion for art simmered beneath the surface. Bright dedicated his leisure hours to sketching and drawing, honing his observational skills and developing a feel for visual representation. The artistic environment of Norwich, a vibrant centre for landscape painting, undoubtedly played a crucial role. He sought formal instruction, becoming a pupil of Alfred Stannard (1806-1889), a notable member of the Norwich School known for his river scenes and landscapes.

This period was formative. Bright absorbed the influences of the local artistic milieu. He was particularly inspired by the work of prominent Norwich School figures such as John Berney Crome (1794-1842), son of the school's founder, and the highly innovative John Sell Cotman (1782-1842). Their emphasis on depicting the local Norfolk landscape, their mastery of light and structure, and their experimentation with different mediums provided a strong foundation upon which Bright would build his own artistic identity. His early works began to reflect this grounding in careful observation and a love for the East Anglian environment.

Transition to London and Broadening Horizons

The year 1836 marked a significant turning point in Bright's life and career. He made the decisive move from Norwich to Paddington, London. This relocation signalled his commitment to pursuing art professionally and placed him at the heart of the British art world, offering greater opportunities for exhibition, patronage, and interaction with fellow artists. London provided a larger stage and access to institutions like the Royal Academy and the British Institution.

Bright's artistic practice was diverse in terms of medium. While accomplished in oils, he became particularly celebrated for his watercolours and his skillful use of chalks and pastels. He even developed and marketed his own brand of crayons under the name "Bright's Crayons," distinguished by a "B" mark, catering to fellow artists and amateurs and indicating his engagement with the practical tools of his trade. His proficiency in these drawing media allowed for rapid sketching outdoors, capturing fleeting effects of light and weather, which often formed the basis for more finished studio works.

His subject matter expanded significantly beyond his native East Anglia. Bright became an inveterate traveller, undertaking numerous sketching tours throughout the British Isles. He depicted the rugged landscapes of Scotland, the picturesque valleys and coasts of Wales, and scenic spots across England, including Devon, Kent, and Yorkshire. These journeys provided a constant source of fresh inspiration and material, resulting in a body of work that celebrated the varied beauty of Britain's natural and man-made heritage, from tranquil rivers and dense woodlands to dramatic coastlines and crumbling abbey ruins.

The Norwich School Connection

While Henry Bright moved to London and developed a national reputation, his artistic roots remained intertwined with the Norwich School. This school, flourishing primarily in the first half of the 19th century, is recognised as the first significant provincial art movement in Britain. Founded by artists like John Crome (1768-1821) and later dominated by figures such as John Sell Cotman, the school was characterised by its dedication to depicting the local Norfolk landscape, often drawing inspiration from Dutch Golden Age landscape painting in its realism and attention to light and atmosphere.

Bright is generally considered a member of the later generation or phase of the Norwich School. His initial training under Alfred Stannard and his admiration for John Berney Crome and John Sell Cotman firmly place him within its sphere of influence. His early works often share the school's focus on intimate East Anglian scenes, careful draughtsmanship, and sensitivity to natural effects.

However, Bright's career trajectory diverged from the more localized focus of many earlier Norwich painters. His move to London, extensive travels, and engagement with a wider circle of artists, including J.M.W. Turner, broadened his style and subject matter. While retaining the observational acuity fostered by his Norwich beginnings, his later work often displayed a more dramatic flair and a brighter palette, reflecting broader Victorian tastes and his own evolving artistic personality. He successfully bridged the regional tradition with the mainstream London art scene.

Influential Friendships: Turner and Contemporaries

A pivotal aspect of Henry Bright's career was his association with Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851), arguably the greatest British landscape painter. Bright established a strong friendship with the elder artist and is known to have accompanied Turner on several sketching trips. This connection was immensely beneficial; Turner reportedly admired Bright's work, and such esteem from a figure of Turner's stature undoubtedly enhanced Bright's reputation and visibility.

The association with Turner likely influenced Bright's own handling of light and atmosphere, encouraging a bolder approach to colour and composition in some of his works. Furthermore, Turner's endorsement is said to have helped Bright secure important patrons, contributing significantly to his professional success. The relationship highlights Bright's ability to connect with and earn the respect of the leading artistic figures of his time.

Beyond Turner, Bright cultivated friendships with a wide circle of contemporary artists. These included Samuel Prout (1783-1852), renowned for his picturesque watercolours of European architecture; David Cox (1783-1859), a master of watercolour landscape known for his fresh, breezy style; and James Duffield Harding (1798-1863), another prominent landscape painter, watercolourist, and influential teacher who, like Bright, published instructional art books.

Other artist friends mentioned in records include Henry Jutsum (1816-1869), a landscape painter; George Lance (1802-1864), primarily known for his elaborate still-life compositions; William Collingwood Smith (1815-1887), a prolific watercolourist; and William Leighton Leitch (1804-1883), a distinguished Scottish watercolour painter who, significantly, also served as Queen Victoria's drawing master for many years. These connections demonstrate Bright's active participation in the vibrant artistic community of mid-19th century London and beyond. His travels also brought him into contact with artists on the continent, sketching in the Netherlands, France, and the German states (including Prussia).

Teaching, Publications, and Artistic Materials

Henry Bright was not only a practicing artist but also a respected and sought-after art tutor. His skills and reputation attracted pupils from affluent backgrounds, including members of the nobility and potentially even royalty, although specific names beyond anecdotal references are scarce. His role as an instructor suggests a methodical approach to art and an ability to communicate techniques effectively, complementing his own diverse practice.

His commitment to art education extended to publishing. Bright authored and published drawing manuals, contributing to the popular Victorian market for instructional art books. These publications likely codified the methods he employed in his own work and teaching, covering techniques for landscape drawing and potentially the use of different media like watercolour and chalk. Such books played a role in disseminating artistic knowledge and encouraging amateur art practice during the period.

A unique aspect of his engagement with the practical side of art was the development and marketing of "Bright's Crayons." These coloured chalks or pastels, typically marked with a distinctive "B," were sold for artistic use. This venture indicates Bright's deep understanding of his materials and a possible desire to provide artists with high-quality tools, perhaps reflecting his own frequent use of chalks for sketching and finished works. It positions him not just as a creator but also as an enabler of artistic practice for others.

Notable Works and Exhibition History

Throughout his career, Henry Bright was a regular exhibitor at London's major art institutions, ensuring his work was seen by critics, collectors, and the public. He began exhibiting in London around 1836, coinciding with his move there. His works frequently appeared at the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts, the British Institution, and the Society of British Artists on Suffolk Street.

A significant affiliation was with the New Society of Painters in Water Colours (later the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours). He was elected a member in 1839, confirming his standing as a leading watercolourist early in his London career. Exhibiting with this society provided a dedicated venue to showcase his achievements in that medium alongside peers like David Cox and William Collingwood Smith.

One of his most celebrated works is The Ruins of Bolton Priory, Yorkshire, exhibited possibly around 1844 or 1845. This painting gained significant recognition when it was purchased by Queen Victoria. Royal patronage was highly coveted and significantly boosted an artist's status and desirability among other collectors. The choice of a picturesque ruin subject was popular in the Romantic era, and Bright's skillful rendering clearly impressed the monarch.

Another documented work is Entrance to an Old Prussian Town, shown at the British Institution in 1839, reflecting his continental travels. Later works exhibited at the Royal Academy included Winter Scene and the intriguingly titled A Frog and Lobster Fight, both shown in 1869. While primarily a landscape painter, the latter title suggests occasional forays into more whimsical or narrative subjects. A painting titled Shrubland Park, depicting the Suffolk estate, likely dates from the 1840s and remains a key example of his handling of English parkland scenery.

His output ranged from rapid, atmospheric sketches, often in chalk or watercolour, which captured immediate impressions, to large, highly finished oil paintings intended for exhibition. While auction records indicate that his sketches and smaller works can sometimes be acquired relatively modestly, his major exhibition pieces, particularly large panoramic landscapes, were and remain highly regarded and command significant prices, reflecting their ambition and technical accomplishment.

Style, Technique, and Artistic Vision

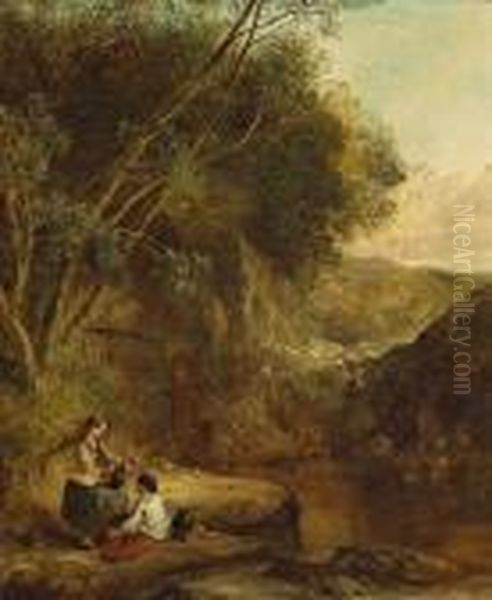

Henry Bright's artistic style is characterized by its vibrancy, technical assurance, and deep appreciation for the nuances of the natural world. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture atmospheric effects – the quality of light filtering through trees, the drama of gathering storm clouds, the dampness after rain, or the crispness of a winter day. His skies are often particularly noteworthy, dynamic elements within the composition rather than mere backdrops.

His use of colour was often bold and rich, moving beyond the sometimes more muted palettes of the earlier Norwich School painters towards a brighter, more typically Victorian sensibility, though always grounded in observation. In his watercolours, he employed a range of techniques, from transparent washes to the use of bodycolour (gouache) for highlights and textural effects, achieving both delicacy and strength. His oil paintings often display vigorous brushwork and a confident handling of paint, building up textures and forms effectively.

Bright's proficiency with chalks and pastels allowed him a directness and immediacy, particularly suited for capturing fleeting moments outdoors. These works often possess a remarkable freshness and spontaneity. Across all media, his draughtsmanship was strong, defining forms clearly while integrating them into a cohesive overall composition. He excelled at rendering the textures of nature – the roughness of bark, the solidity of rock, the foliage of trees, and the reflective surfaces of water.

His compositions varied from intimate woodland scenes and studies of decaying structures to expansive panoramic views. He had a particular fondness for subjects that combined the natural and the man-made, such as castles or abbeys nestled within landscapes, exploring themes of time, nature's endurance, and the picturesque. His overall vision was one that celebrated the beauty and diversity of the landscape, rendered with both technical skill and genuine affection.

Extensive Travels and Sources of Inspiration

Travel was fundamental to Henry Bright's artistic practice, providing a continuous stream of new subjects and visual stimuli. While his roots were in Suffolk and Norfolk, his ambition and curiosity led him far beyond East Anglia. His sketching tours across the British Isles were extensive. Scotland offered dramatic Highland scenery, lochs, and castles. Wales provided mountains, valleys, and coastal views.

Within England, he explored numerous regions. The Lake District, Devon, Cornwall, Kent, Surrey, and Yorkshire all featured in his itineraries, each offering distinct landscape characteristics. He seemed particularly drawn to river valleys, ancient woodlands, coastal areas, and sites with historical resonance, such as ruined abbeys (like Bolton Priory) or castles. Ireland also featured among his destinations.

His travels were not confined to Britain. Bright ventured onto the continent, sketching along the Rhine River valley in Germany, exploring the Netherlands with its distinctive flat landscapes and waterways (reminiscent perhaps of the Dutch masters admired by the Norwich School), and visiting parts of France and Prussia. These continental tours introduced different architectural styles and landscape types into his repertoire, as evidenced by works like Entrance to an Old Prussian Town.

These journeys were working trips. Bright would fill sketchbooks with drawings and watercolours made on the spot. These studies served as an invaluable resource back in his London studio, providing the raw material for larger, more elaborate paintings intended for exhibition or sale. This practice of extensive travel and outdoor sketching was common among landscape painters of the era, but Bright pursued it with particular energy, resulting in a remarkably diverse geographical range in his oeuvre.

Patronage, Recognition, and Anecdotes

Henry Bright achieved considerable success during his lifetime, gaining recognition from important patrons and institutions. The purchase of The Ruins of Bolton Priory by Queen Victoria in the mid-1840s was a significant coup, lending royal endorsement to his work and undoubtedly attracting other wealthy collectors. He also taught members of the aristocracy, further cementing his position within elite circles. His work was acquired by collectors not only in Britain but also reportedly on the continent.

His regular presence at major London exhibitions ensured critical attention, and reviews in publications like the Fine Art Trade Journal praised his work. One such review commended him as "a painter who loves the nooks and corners of rustic Nature," highlighting the "poetical beauty" found in his depictions of seemingly simple scenes. This suggests an appreciation for his ability to find charm and significance in everyday rural landscapes, as well as in more dramatic subjects.

While detailed accounts of his personal life are limited, one charming anecdote survives concerning his travels. During a trip to Brodick Castle on the Isle of Arran, Scotland, he reportedly carried the Grand Duchess Marie Alexandrovna of Russia (daughter of Tsar Alexander II and later Duchess of Edinburgh) across a stream. This incident, likely occurring during a sketching expedition attended by aristocratic company, offers a glimpse into the social circles Bright sometimes moved in and his experiences beyond the studio.

His development of "Bright's Crayons" also speaks to his practical engagement with the art world and his reputation among fellow artists who would have been the primary market for such materials. His membership in the New Society of Painters in Water Colours and his consistent acceptance at the Royal Academy further attest to the respect he commanded within the professional art establishment of Victorian Britain.

Later Life and Death

Details about Henry Bright's later years are less extensively documented than his active exhibiting period. He continued to paint and exhibit into the late 1860s, with works appearing at the Royal Academy as late as 1869. It is likely he maintained his studio practice and potentially continued teaching, although perhaps at a reduced pace.

His connection to Suffolk remained, despite his long residence in London. He eventually returned to his home region towards the end of his life. Henry Bright passed away in Ipswich, the county town of Suffolk, on 21 September 1873, at the age of 63. His death marked the end of a prolific and successful career dedicated to the depiction of landscape.

Legacy and Critical Reception

Henry Bright left behind a substantial body of work that continues to be appreciated for its technical skill, vibrant colour, and affectionate portrayal of landscape. He is firmly established as an important figure within the later Norwich School, demonstrating how the school's principles could be adapted and integrated into the broader currents of Victorian art. His ability to work masterfully across different media – oil, watercolour, and particularly chalk/pastel – marks him as a versatile and accomplished technician.

His legacy is preserved in numerous public collections. His works can be found in major national institutions like the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, as well as in regional galleries, particularly the Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery, which holds a significant collection related to the Norwich School. His paintings continue to appear on the art market, attracting collectors interested in British landscape painting of the 19th century.

Critically, Bright is viewed as a significant link between the earlier landscape traditions, building on the foundations laid by artists like Thomas Gainsborough (who also had Suffolk roots) and John Constable, and the evolving tastes of the Victorian era. While perhaps not as revolutionary as his friend J.M.W. Turner, Bright excelled at creating appealing, well-crafted landscapes that captured the public imagination. The contemporary praise for his "poetical beauty" and love for "rustic Nature" reflects an enduring appreciation for his ability to convey the charm and atmosphere of the places he depicted.

His role as a teacher and publisher of drawing materials also forms part of his legacy, contributing to the dissemination of artistic practice in the 19th century. He remains a respected name, recognised for his contribution to British landscape art and his skillful chronicling of the diverse scenery of his homeland and beyond.

Conclusion

Henry Bright navigated the 19th-century British art world with considerable skill and success. From his early training within the influential Norwich School to his establishment as a respected London-based artist with royal patronage and connections to figures like J.M.W. Turner, he forged a distinctive artistic identity. His prolific output across multiple media captured the varied landscapes of Britain and Europe with vibrancy, technical flair, and a palpable love for nature. As a painter, tutor, and even supplier of artists' materials, Bright made a multifaceted contribution to the art of his time. His works endure as testaments to his talent and provide a captivating visual record of the landscapes he explored, securing his position as a significant master of the English landscape tradition.