Samuel Bough stands as a significant, if sometimes ruggedly individualistic, figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century British art. Though English by birth, his career unfolded primarily in Scotland, where he became one of the most recognisable and prolific landscape painters of his generation. Active from the 1840s until his death in 1878, Bough developed a vigorous, atmospheric style, particularly renowned in watercolour, that captured the dynamic environments of the Scottish coasts, estuaries, and countryside. His journey from a shoemaker's son and reluctant apprentice to a full member of the Royal Scottish Academy is a testament to his innate talent and determined pursuit of an artistic life outside conventional pathways.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Samuel Bough was born in Carlisle, Cumberland (now Cumbria), England, on January 8, 1822. His father was a shoemaker, a background far removed from the established art world. Young Bough showed an early inclination towards drawing but displayed a marked aversion to formal education, reportedly running away from school on at least two occasions to return home. This independent, perhaps rebellious, streak would characterise much of his life and career. His artistic development was largely driven by his own observations and practice, marking him as essentially self-taught.

His family, perhaps recognising his artistic leanings or seeking a respectable trade for him, arranged an apprenticeship with Thomas Allom, a London-based architect and topographical artist who also worked as an engraver. Bough moved to London to pursue this path, but the meticulous and often repetitive work of engraving failed to hold his interest. He found the constraints of the profession stifling and soon abandoned the apprenticeship, returning once more to his native Carlisle. This early rejection of a structured, conventional route into the arts solidified his path as an independent learner, relying on observation and personal experimentation.

Back in Carlisle and its surroundings, Bough began to focus more seriously on sketching and painting the local landscape. The countryside of Cumberland and the nearby Solway Firth offered ample subjects. It was during this formative period that he likely honed his skills in observation and began developing his handling of watercolour, a medium that would become central to his artistic output. He sought subjects in nature, learning directly from the landscapes he encountered, a practice common among aspiring landscape artists of the era, following the examples set by earlier masters like John Constable and J.M.W. Turner.

Theatrical Beginnings: A Painter of Scenes

A pivotal shift occurred in 1845 when Bough moved to Manchester. There, he secured employment not in the fine arts sphere directly, but as a scene painter for the Theatre Royal. This role, while practical and providing an income, proved unexpectedly influential on his artistic development. Scene painting required working on a large scale, quickly blocking in compositions, and creating dramatic effects of light and atmosphere capable of registering from a distance. This experience likely fostered the boldness, speed, and confidence that would later characterise his landscape paintings.

Working in the theatre demanded versatility and the ability to rapidly evoke different moods and settings. Bough learned to handle paint broadly and effectively, mastering techniques for suggesting space, weather, and time of day with economy and impact. While continuing his theatre work, he did not abandon his personal artistic pursuits. He continued to sketch and paint watercolours, applying his growing skills to landscape subjects whenever possible. His time in Manchester provided practical training and exposure that formal art schooling might not have offered in quite the same way.

His theatrical career continued when he moved to Glasgow in 1847, taking up a similar position as a scene painter. Glasgow, a burgeoning industrial city on the River Clyde, offered new environments and subjects. The bustling river traffic, the surrounding countryside, and the dramatic western Scottish weather provided rich material for his developing landscape interests. The skills honed in the theatre—strong composition, atmospheric effects, and efficient execution—were increasingly channelled into his easel paintings, primarily watercolours during this period. This practical grounding gave his work a certain robustness and directness.

Emergence as a Landscape Specialist

By the late 1840s or early 1850s, Bough made the decisive move to abandon scene painting and dedicate himself entirely to landscape art. He initially settled in Hamilton, near Glasgow, before eventually moving to the vicinity of Edinburgh around 1855. This transition marked the beginning of his mature career as one of Scotland's leading landscape painters. He found the landscapes of Scotland, particularly the coastal areas, estuaries, and river valleys, profoundly inspiring. The Firth of Forth, the Fife coastline, the Clyde estuary, and parts of the Highlands became recurring subjects.

His style began to fully emerge during this period. It was characterised by a vigorous, often rapid execution, aiming to capture the transient effects of light and weather. He excelled at depicting breezy days, gathering storms, luminous sunsets, and the interplay of light on water. While capable of detailed observation, his primary focus was often on the overall atmospheric mood and the dynamic energy of the scene. His background in scene painting perhaps contributed to his ability to create compelling compositions that balanced topographical elements with dramatic effect.

He worked primarily in watercolour, a medium he handled with remarkable fluency and boldness. His washes could be broad and fluid, yet he was also capable of incorporating finer detail where needed. He sometimes used bodycolour (gouache) to add highlights or opacity, a common practice among Victorian watercolourists. His approach was less about meticulous finish and more about capturing the essence and immediacy of the natural world. This contrasted with the highly detailed style of some contemporaries, aligning him more with artists who prioritised atmospheric truth, such as David Cox, whose influence can sometimes be discerned in Bough's handling.

Style and Technique: Capturing Nature's Moods

Samuel Bough's artistic style is best described as a robust form of naturalism infused with expressive energy. He was deeply committed to observing the natural world, particularly the effects of weather and light, but he translated these observations onto paper or canvas with a distinctive vigour and breadth. His work sits somewhere between the detailed topographical tradition and the more atmospheric, proto-impressionistic tendencies emerging in British art.

His subject matter was diverse but frequently returned to marine and coastal themes. Harbours like Newhaven or St Andrews, estuaries such as the Clyde or the Forth, and shipping scenes were favourite motifs. He captured the bustle of ports, the solitude of windswept beaches, and the drama of vessels battling the elements. Inland, he painted river valleys, castles set within landscapes (like Dumbarton or Cadzow), rural scenes with figures and animals, and occasionally cityscapes, notably views of Edinburgh. He had a particular fondness for depicting specific times of day or weather conditions – bright, windy days with scudding clouds were a hallmark.

In watercolour, his preferred medium, Bough worked with a freedom and directness that was remarkable for his time. He applied washes with confidence, allowing colours to blend wet-into-wet to create soft atmospheric effects, while also using drier brushwork to define forms or textures. His palette was generally naturalistic, though sometimes criticised by later critics for occasional muddiness or a lack of subtlety compared to the luminous transparency achieved by masters like Turner. However, the strength and immediacy of his watercolours were widely admired during his lifetime.

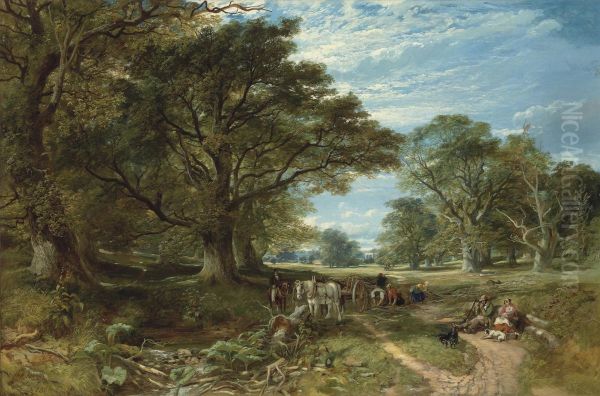

His oil paintings, while less numerous than his watercolours, share a similar energy. The brushwork is often bold and visible, the paint applied with a certain impasto texture. Works like The Baggage Waggon or views of Cadzow Forest in oil demonstrate his ability to handle the medium with force, capturing the textures of foliage, earth, and sky with a direct, almost physical approach. While perhaps lacking the ultimate refinement of some academic painters, his oils possess a powerful sense of place and atmosphere. His experience as a scene painter likely contributed to this confident, broad handling in both media.

Representative Works

Samuel Bough's prolific output includes many notable works that exemplify his style and preferred subjects. Among his most celebrated paintings is Dumbarton Rock on the Clyde. This subject, depicting the dramatic volcanic plug crowned by a castle at the confluence of the Rivers Clyde and Leven, was one he returned to. His versions typically capture the rock under dynamic skies, emphasizing its imposing silhouette against the broad estuary, often with shipping activity in the foreground, showcasing his skill in rendering both landscape and marine elements.

Cadzow Forest, near Hamilton, was another favourite location, famous for its ancient oaks and wild white cattle. Bough painted numerous scenes here, in both oil and watercolour. These works often highlight the gnarled textures of the ancient trees and the play of sunlight filtering through the canopy, sometimes including the cattle to add life and a sense of historical continuity to the landscape. These paintings demonstrate his ability to capture the specific character of a place.

His coastal scenes are perhaps his most characteristic works. Views of St Andrews, Newhaven Harbour, or various locations along the Fife coast often depict fishing boats drawn up on the beach or navigating choppy waters under expansive, cloud-filled skies. These works excel in conveying the brisk, breezy atmosphere of the Scottish coastline. Shipping on the Clyde captures the industrial energy of the river, contrasting with the natural beauty of the surrounding hills.

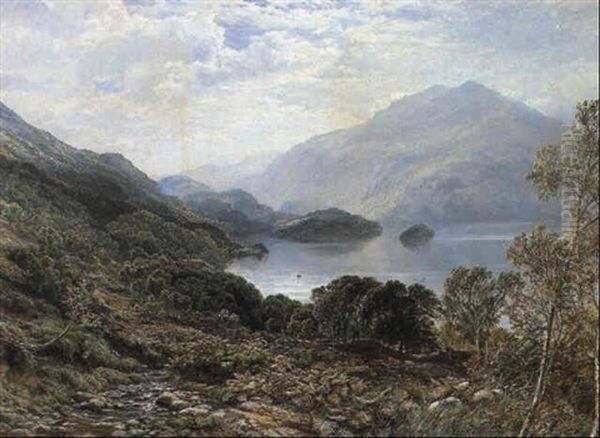

Bough also tackled more specific events or unusual light effects. Edinburgh Fireworks Night (1863), likely depicting celebrations for the wedding of the Prince of Wales, is a fascinating example of his ability to capture nocturnal scenes and artificial light, a challenging subject handled with characteristic boldness. Other works like The Baggage-Waggon show his interest in rural life and genre elements within the landscape. Titles like Ben Nevis indicate his engagement with the grander scenery of the Scottish Highlands, although he is perhaps less associated with sublime mountain landscapes than contemporaries like Horatio McCulloch.

Professional Recognition and Edinburgh Life

Samuel Bough's talent and distinctive style gained increasing recognition within the Scottish art establishment. After settling near Edinburgh in the mid-1850s, he became a prominent figure in the city's artistic circles. His work was regularly exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA), the premier art institution in Scotland. His growing reputation led to his election as an Associate of the RSA (ARSA) in 1857, a significant step in his professional career.

He established a studio in Edinburgh, first in George Street and later moving to a larger space in Jordan Bank, Morningside, which reportedly became a well-known hub for artists and bohemian characters. Bough himself cultivated a somewhat unconventional persona – known for his sociability, his enjoyment of life, and perhaps a certain disregard for strict propriety. This bohemian reputation added to his public profile, making him a colourful figure in the Victorian art world of Edinburgh.

His artistic standing continued to rise, culminating in his election as a full Academician of the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) in 1875. This honour solidified his position as one of Scotland's leading painters. He was encouraged in his career by established figures, notably Sir Daniel Macnee, a prominent portrait painter who served as President of the RSA from 1876 until his death in 1882. Macnee's support would have been valuable, indicating Bough's acceptance within the highest levels of the Scottish art community, despite his unconventional background and self-taught origins.

Throughout his Edinburgh years, Bough remained highly productive, turning out a large number of watercolours and oils that found a ready market among collectors. His work was popular for its recognisable Scottish subjects and its energetic, accessible style. He participated regularly in exhibitions, not only in Scotland but also occasionally in London and other English cities, further broadening his reputation. His success allowed him a comfortable lifestyle, though his finances were sometimes reportedly precarious due to his generous and perhaps improvident nature.

Context, Contemporaries, and Influence

Samuel Bough worked during a vibrant period for landscape painting in Britain. He was a contemporary of the later Pre-Raphaelites, although his style shows little direct connection to their meticulous detail. His work is better understood within the broader Victorian landscape tradition, which built upon the foundations laid by Turner and Constable earlier in the century. In Scotland, he emerged alongside painters like Horatio McCulloch, who specialised in grand, often romanticised, depictions of the Highlands. Bough's focus was often different – more attuned to the working landscapes of the coasts and lowlands, and rendered with a greater sense of immediacy and atmospheric dynamism than McCulloch's sometimes static grandeur.

Another key contemporary was William McTaggart, often considered Scotland's foremost Impressionist painter. While both Bough and McTaggart were fascinated by coastal light and weather, and both worked with increasing freedom, their approaches differed. McTaggart's later work dissolved form into light and colour to a greater degree than Bough's typically more structured compositions. However, Bough's emphasis on capturing transient effects and his bold handling certainly prefigure some aspects of Impressionism, and he is sometimes seen as a precursor to the movement in Scotland.

Other notable Scottish contemporaries included landscape painters like Waller Hugh Paton, known for his detailed renderings, and Keeley Halswelle. Figure painters like George Paul Chalmers were also part of the Edinburgh scene. Bough would have known these artists through the RSA and the general artistic milieu. While his self-taught background set him apart from those trained under Robert Scott Lauder at the Trustees' Academy (the main art school in Edinburgh), his success ensured his integration into the professional art world.

Looking at the wider British context, Bough's robust watercolour style can be compared to that of David Cox or Peter De Wint, though perhaps with a rougher, more vigorous edge. While unlikely to have matched the sublime vision of J.M.W. Turner or the profound naturalism of John Constable, Bough carved out his own distinct niche. His influence on subsequent Scottish painting is perhaps debatable; the next major movement, the Glasgow Boys in the 1880s, looked more towards contemporary French realism and plein-air painting (e.g., Jules Bastien-Lepage). However, Bough's commitment to depicting Scottish landscapes with energy and atmospheric truth undoubtedly contributed to the vitality of the national school. Artists like Arthur Melville, known for his dazzling watercolours, might be seen as inheriting some of Bough's boldness in the medium, albeit with a more modern sensibility.

Later Years and Legacy

Samuel Bough continued to paint prolifically throughout the 1860s and 1870s. His work remained popular with the public and collectors, ensuring a steady demand. He maintained his Edinburgh studio and his active participation in the city's art life. His election to full RSA membership in 1875 marked the peak of his official recognition. His subjects remained largely consistent, focusing on the Scottish landscapes and seascapes he knew so well, rendered in his characteristic energetic style.

However, his health began to decline in his later years. Samuel Bough died in Edinburgh on November 19, 1878, at the relatively young age of 56. His death marked the end of a career that had significantly shaped the course of Scottish landscape painting in the mid-Victorian era. He left behind a substantial body of work, primarily watercolours, but also numerous oils, scattered across public and private collections.

Historically, Bough's reputation has remained strong, particularly within Scotland. He is consistently recognised as a major figure in the Scottish school of landscape painting. His strengths are seen in his vigorous handling, his ability to capture atmosphere and movement, and his authentic depiction of Scottish coastal and rural life. His watercolours, in particular, are often praised for their freshness and immediacy. He successfully bridged the gap between topographical rendering and more expressive, atmospheric interpretation.

Criticism sometimes focuses on a perceived lack of variation in his later work, suggesting that his style could become formulaic. Some critics have pointed to occasional weaknesses in his colour or a certain coarseness in execution compared to more refined contemporaries. The snippets provided also mention a potential lack of "humour" or "independent character" possibly limiting his depth, reflecting a critical perspective perhaps related to his sometimes straightforward, robust approach. Despite these caveats, his overall contribution is undeniable. He brought a distinctive energy and a focus on the dynamic aspects of nature to Scottish art.

Conclusion

Samuel Bough remains a vital and engaging figure in the history of British art. An Englishman who became one of Scotland's most characteristic landscape painters, his journey from humble beginnings through the practical world of scene painting to academic recognition is compelling. His art, particularly his watercolours, captures the spirit of the Scottish landscape – its changing weather, its dramatic coasts, its working rivers – with a boldness and immediacy that continues to resonate. While perhaps lacking the profound subtlety of a Turner or the revolutionary impact of the later Impressionists, Bough's vigorous naturalism and mastery of atmospheric effect secured him a lasting place. He stands as a testament to the power of self-directed talent and a defining force in the rich tradition of Scottish landscape painting. His work offers a robust, honest, and often exhilarating vision of the natural world as he experienced it.