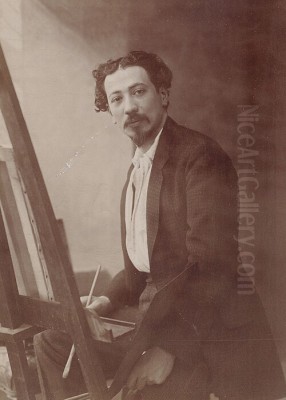

Henry Caro-Delvaille stands as a fascinating figure in the art world of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A painter who navigated the shifting tides of artistic taste from the Belle Époque in Paris to the burgeoning society of early 20th-century America, his work offers a window into a world of refined aesthetics, intimate portraiture, and decorative elegance. While perhaps not as universally recognized today as some of his avant-garde contemporaries, Caro-Delvaille carved out a significant career, celebrated for his technical skill and his ability to capture the spirit of his subjects and his era.

Nationality and Foundational Identity

Born Henri Caro-Delvaille on July 6, 1876, in Bayonne, a picturesque town in the French Basque Country, his roots were deeply embedded in French soil. He was of French nationality, a fact that shaped his initial artistic education and his early career within the established Parisian art scene. His family background was Sephardic Jewish, a heritage that, while not always overtly prominent in his art's subject matter, formed part of his personal identity in an era of complex social and cultural dynamics in Europe.

Caro-Delvaille's primary identity was that of a painter. He dedicated his life to the visual arts, specializing in portraiture, genre scenes, and particularly, sensuous depictions of the female nude. His work often exuded an air of intimacy and quiet contemplation, characteristics that distinguished him even as he adapted his style to different contexts and clienteles throughout his career. He was a product of the rigorous academic training system but was also receptive to the more modern aesthetic currents of his time, creating a body of work that balanced tradition with a subtle contemporary sensibility.

Formative Years and Artistic Ascent

Henry Caro-Delvaille's artistic journey began in his hometown of Bayonne, where he likely received his initial instruction. Recognizing his talent, he moved to Paris, the undisputed art capital of the world at the time, to further his education. From 1895, he enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, a bastion of academic art training. There, he became a student of the renowned painter Léon Bonnat, who was also from Bayonne. Bonnat, known for his powerful portraits and his admiration for Spanish masters like Diego Velázquez and Jusepe de Ribera, exerted a significant influence on the young Caro-Delvaille, instilling in him a strong foundation in draftsmanship and a rich, often somber, palette in his early works.

His talent was quickly recognized. Caro-Delvaille began exhibiting at the Salon des Artistes Français in 1897, making a notable debut. His success continued, and in 1901, he was awarded a third-class medal at the Salon for his painting La manucure (The Manicure). This early acclaim helped to establish his reputation within the competitive Parisian art world. He became an associate of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1903 and a full member in 1904, a testament to his rising stature. In 1905, his painting Ma femme et ses sœurs (My Wife and Her Sisters), depicting his wife Aline and her siblings, earned him the prestigious Gold Medal at the Salon, cementing his position as a respected artist. He would later serve as secretary of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, indicating his active involvement in the institutional art scene.

Transatlantic Shifts and Later Career

The early 20th century brought significant changes for Caro-Delvaille. Around 1913, or shortly thereafter with the outbreak of World War I, he made a pivotal decision to move to the United States. This move marked a new chapter in his life and career. Settling primarily in New York City, he found a receptive audience among the American social elite. His European training and sophisticated style appealed to wealthy patrons seeking elegant portraits and decorative works for their homes.

In America, Caro-Delvaille continued to paint portraits, often of prominent figures, and also undertook commissions for decorative murals and panels. His style, while retaining its characteristic refinement, sometimes adapted to the tastes of his new environment, perhaps becoming somewhat brighter or more overtly decorative in certain instances. He exhibited his work in various American cities, including New York, Chicago, and Buffalo, further expanding his reputation on the other side of the Atlantic. Artists like John Singer Sargent had already paved the way for European-trained portraitists to find success in the U.S., and Caro-Delvaille benefited from this established market.

Despite his success in America, Caro-Delvaille maintained connections with Europe. He traveled between the continents and eventually returned to Europe. The later years of his career saw him continue to work, though perhaps with less of the high-profile visibility he had enjoyed earlier. He passed away in Paris in July 1928, leaving behind a legacy as an artist who successfully bridged European tradition and American modernity.

Anecdotes, Social Circles, and Subtle Controversies

While Henry Caro-Delvaille's career was not marked by overt, scandalous controversies in the way some of his avant-garde contemporaries courted public outrage, his life and work were not without interesting facets and subtle points of discussion. His marriage in 1907 to Aline de Glass (née Dujardin-Beaumetz), an actress and writer, connected him to the literary and theatrical circles of Paris. Aline was the niece of Étienne Dujardin-Beaumetz, a politician and Under-Secretary of State for Fine Arts, which likely provided Caro-Delvaille with further access to influential figures in the art world and high society.

One notable friendship was with the celebrated playwright Edmond Rostand, author of Cyrano de Bergerac. Caro-Delvaille painted several portraits of Rostand and his family, and these works are considered among his finest. This connection underscores his integration into the cultural elite of France. The intimacy and psychological insight in these portraits suggest a close rapport between artist and sitter.

The "controversy," if one could call it that, surrounding Caro-Delvaille's work might lie more in its positioning within the art historical narrative. He was a highly skilled artist working in a predominantly figurative and elegant style during a period when radical movements like Fauvism (with artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain) and Cubism (led by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque) were fundamentally challenging the nature of art. His adherence to a more traditional, albeit refined, aesthetic meant that he was sometimes seen as less "progressive" than these revolutionaries. However, his focus on sensuous nudes, often depicted in intimate, boudoir settings, could be seen as subtly challenging conservative tastes, treading a fine line between academic propriety and a more modern, personal exploration of the female form. These works, while not shocking in the manner of Manet's Olympia decades earlier, possessed a quiet eroticism that was very much of its time.

His move to the United States could also be viewed through the lens of artistic strategy. While Europe was increasingly dominated by modernist experimentation, America offered a thriving market for skilled portraitists and decorative painters who could cater to the tastes of a wealthy clientele eager to emulate European sophistication. This pragmatic approach to his career ensured his continued success.

The Essence of Caro-Delvaille: Artistic Style and Signature Works

Henry Caro-Delvaille's artistic style evolved throughout his career, yet it consistently retained a signature elegance, technical proficiency, and a focus on the human figure, particularly women. His early works, influenced by his academic training under Léon Bonnat, show a mastery of draftsmanship, a rich, often darker palette, and a debt to Spanish masters like Velázquez. This is evident in the solidity of form and the psychological depth he sought in his early portraits and genre scenes.

As he matured, his style became more refined and infused with a subtle sensuality. While still grounded in realism, his figures often took on an idealized quality, and his compositions became more decorative. There's a discernible influence of Symbolism in the mood and atmosphere of some pieces, and a touch of Art Nouveau in the flowing lines and decorative elements, particularly in his treatment of fabrics and interiors. He excelled at capturing textures – the sheen of silk, the softness of velvet, the warmth of skin – which added to the luxurious feel of his paintings.

His nudes are a significant part of his oeuvre. Works like Le Sommeil de Manon (Manon's Sleep) or La Paresse (Idleness) depict women in relaxed, intimate poses, often asleep or in moments of quiet reverie. These are not the heroic nudes of classical mythology but rather modern women in contemporary settings, rendered with a delicate eroticism and a focus on graceful lines and subtle color harmonies. He often employed a soft, diffused light that enhanced the dreamlike quality of these scenes.

Representative Works:

La manucure (The Manicure, 1901): An early success that demonstrated his skill in genre painting and capturing intimate, everyday moments with a sense of quiet observation. This work helped establish his reputation at the Salon.

Ma femme et ses sœurs (My Wife and Her Sisters, 1905): This large-scale group portrait, featuring his wife Aline de Glass and her sisters, was a triumph at the Salon, earning him a gold medal. It showcases his ability to handle complex compositions, render individual likenesses with sensitivity, and create an atmosphere of bourgeois domesticity and elegance. The interplay of figures and the sophisticated use of color and light are notable.

Le Sommeil de Manon (Manon's Sleep, c. 1907): A quintessential example of his sensuous nudes. The painting depicts a sleeping woman in a luxurious interior, her body rendered with soft contours and a warm palette. It embodies the intimate and dreamlike quality prevalent in much of his work focusing on the female form. This work is often cited as one of his most characteristic pieces.

Portraits of Edmond Rostand and his family: These portraits, including those of the playwright himself and his wife Rosemonde Gérard, are celebrated for their psychological insight and elegant execution. They reflect a personal connection between the artist and his sitters, moving beyond mere likeness to capture personality and status.

La Paresse (Idleness): Another significant nude, this work, like Le Sommeil de Manon, emphasizes languor and intimacy. The careful arrangement of drapery and the relaxed pose of the figure contribute to a sense of quiet sensuality and decorative harmony.

Portraits from his American period: While specific titles might be less universally known, his portraits of American socialites and prominent figures from the 1910s and 1920s were crucial to his success in the United States. These works continued his elegant style, adapting it to the expectations of a new clientele. Examples include portraits like that of Mrs. Henry G. Dearth.

Decorative Panels and Murals: Caro-Delvaille also undertook commissions for larger decorative schemes, often for private residences. These works allowed him to explore more expansive compositions and integrate his figures into harmonious interior designs, reflecting an affinity with artists like Pierre Puvis de Chavannes or even some aspects of the work of James McNeill Whistler in terms of decorative intent.

Caro-Delvaille's style, therefore, can be seen as a sophisticated blend of academic tradition, particularly in its emphasis on drawing and form, with fin-de-siècle aestheticism, characterized by elegance, sensuality, and a decorative sensibility. He was a master of creating mood and capturing the refined atmosphere of his subjects' lives.

A Network of Influence: Teachers, Peers, and Artistic Currents

Henry Caro-Delvaille's artistic development and career were shaped by a network of relationships and influences, typical of an artist working within the established structures of the early 20th-century art world.

Teachers and Mentors:

The most significant pedagogical influence was undoubtedly Léon Bonnat (1833-1922). Bonnat was a towering figure in French academic art, known for his powerful portraits, religious scenes, and his role as a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts. His emphasis on strong draftsmanship, anatomical accuracy, and the study of Old Masters, particularly Spanish painters like Velázquez and Ribera, left an indelible mark on Caro-Delvaille's early technique and approach. Bonnat's own Basque origins likely created an initial bond with his student from Bayonne.

Peers and Contemporaries – The Parisian Milieu:

In Paris, Caro-Delvaille was part of a vibrant art scene. He exhibited alongside many prominent artists at the Salons of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. His contemporaries included:

Jacques-Émile Blanche (1861-1942): A fellow society portraitist known for his elegant and psychologically astute depictions of the artistic and literary elite.

Giovanni Boldini (1842-1931): An Italian artist based in Paris, famous for his flamboyant and dynamic portraits of high-society women, characterized by energetic brushwork.

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925): Though American, Sargent was a dominant figure in international portraiture, including in Paris. His virtuoso technique and glamorous depictions set a high bar.

Ignacio Zuloaga (1870-1945): A Spanish painter who also found success in Paris, known for his dramatic and often somber portrayals of Spanish life, reflecting a shared interest in Spanish artistic traditions.

Lucien Simon (1861-1945): A painter known for his depictions of Breton life and intimate family scenes, often exhibiting a similar sensitivity to Caro-Delvaille.

Charles Cottet (1863-1925): Another artist associated with Brittany, known for his somber and powerful maritime scenes and depictions of mourning.

While Caro-Delvaille's style was distinct, he operated within this broader context of artists who, to varying degrees, balanced traditional techniques with modern sensibilities. He was also aware of, though stylistically distant from, the more radical avant-garde movements. Figures like Henri Matisse (1869-1954) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) were revolutionizing painting during Caro-Delvaille's peak years in Paris.

Influences and Affinities:

Beyond direct contemporaries, Caro-Delvaille's work shows affinities with broader artistic currents:

Symbolism: The introspective mood, dreamlike qualities, and focus on suggestion rather than explicit narrative in some of his nudes and allegorical pieces connect him to Symbolist painters like Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824-1898), particularly in the realm of decorative painting, and perhaps more subtly to the intimate Symbolism of artists like Eugène Carrière (1849-1906) in terms of mood.

Art Nouveau: The elegant, flowing lines, decorative patterns, and emphasis on harmonious design in his compositions, especially in interiors and depictions of fabric, show a sensitivity to Art Nouveau aesthetics, though he never fully embraced its more stylized excesses.

Whistlerian Aesthetics: The concern for harmonious color arrangements and the creation of an overall mood, particularly in his more decorative pieces, echoes some of the principles championed by James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903).

The American Context:

Upon moving to the United States, Caro-Delvaille entered a different artistic landscape. He would have been aware of American portraitists like Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942) and the continuing influence of Sargent. His European sophistication was a key selling point in a country where patrons often looked to Europe for cultural validation.

Caro-Delvaille did not seem to have formal students in the way Bonnat did, but his work would have been seen and potentially emulated by younger artists interested in elegant figuration. His primary interactions were likely with fellow exhibitors, patrons, and critics, rather than in a formal teaching capacity. His network was one of professional association and shared cultural spaces, reflecting the interconnectedness of the art world in the major capitals where he worked.

Navigating the Art World: Competition and Collaboration

The art world of Henry Caro-Delvaille's time was a dynamic arena of competition and, to a lesser extent, collaboration. His career unfolded primarily within the framework of the Parisian Salons and later, the gallery system and private commissions in both Europe and America.

Competition:

The most evident form of competition was within the Salon system itself. The Salon des Artistes Français and the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (where Caro-Delvaille primarily exhibited after his initial successes) were juried exhibitions where thousands of artists vied for limited wall space, critical attention, state purchases, and prestigious awards (medals, honors). Caro-Delvaille's early medals were crucial for establishing his reputation amidst a crowded field. He competed directly with other portraitists and genre painters like those mentioned previously – Jacques-Émile Blanche, Giovanni Boldini, Lucien Simon, and others who specialized in elegant depictions of contemporary life or intimate scenes.

Beyond the Salons, competition existed for private commissions, especially in portraiture. Wealthy patrons in Paris, London, and New York had a choice of skilled artists. Caro-Delvaille's ability to capture not just a likeness but also an air of sophistication and status was key to his success in this competitive market. He was competing with artists like Philip de László (1869-1937) in Europe and established American portraitists.

A broader, more ideological form of competition came from the burgeoning avant-garde movements. While Caro-Delvaille was achieving success with his refined, figurative style, artists like Matisse, Picasso, Braque, and the Fauves and Cubists were challenging the very foundations of Western art. This created a parallel art world, and while there might not have been direct "competition" for the same patrons initially, the critical discourse increasingly favored the modernists. Caro-Delvaille and artists of his ilk represented a continuation of a certain tradition, which, while popular with many collectors, was seen as less innovative by proponents of modernism.

Collaboration:

Direct artistic collaboration in the sense of co-painting was rare for artists like Caro-Delvaille, whose work was highly personal in its execution. However, collaboration occurred in other forms:

Artistic Societies: Membership in organizations like the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts involved a degree of collaboration. Artists served on committees, organized exhibitions, and worked together to promote their collective interests. Caro-Delvaille's role as secretary of this society indicates active participation.

Decorative Commissions: When undertaking large-scale decorative projects, such as murals for private residences or public buildings, painters often had to collaborate with architects, interior designers, and sometimes other craftsmen. The successful integration of a painting into an architectural space required careful planning and coordination. While specific collaborations are not always well-documented, this was a common aspect of decorative art.

Thematic Exhibitions: Artists often participated in group exhibitions organized around specific themes or national schools, which could be seen as a form of collective presentation, if not direct collaboration on artworks.

Relationships with Dealers and Gallerists: As the gallery system grew in importance, artists collaborated with dealers like Georges Petit or Durand-Ruel (though Durand-Ruel was more associated with the Impressionists) to promote and sell their work. This was a business collaboration crucial for reaching collectors.

Caro-Delvaille's career demonstrates a skillful navigation of this competitive environment. He built a strong reputation through the Salons, cultivated relationships with influential patrons like Edmond Rostand, and successfully transitioned his practice to the American market when opportunities arose. His "collaboration" was more in terms of participating in the established structures of the art world and working with other professionals to realize his artistic and commercial goals.

Legacy in Collections and the Art Market

Henry Caro-Delvaille's paintings, though perhaps not as ubiquitous in major international museums as works by leading Impressionists or Modernists, are held in a number of significant public collections, particularly in France and the United States. His presence in these institutions ensures his continued visibility and accessibility for study and appreciation.

Museum Collections:

In France, his work is naturally well-represented. Key institutions include:

Musée d'Orsay, Paris: As the premier museum for 19th and early 20th-century French art, the Musée d'Orsay holds important works by Caro-Delvaille, including his celebrated Salon piece, Ma femme et ses sœurs (My Wife and Her Sisters, 1905), and Le Sommeil de Manon.

Musée Bonnat-Helleu, Bayonne: Given his origins in Bayonne and his tutelage under Léon Bonnat, it is fitting that the museum dedicated to his teacher also houses works by Caro-Delvaille.

Musée Basque et de l'histoire de Bayonne, Bayonne: This museum also holds works, reflecting his connection to his native region.

Other French regional museums, such as the Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, and museums in Bordeaux, Lille, and Nice, also have examples of his paintings, often acquired during his lifetime through state purchases at the Salons or later bequests.

In the United States, his works can be found in collections, often as a result of his period working there:

His portraits of American society figures may be held in smaller regional art museums, historical societies, or university collections, sometimes as part of family bequests. For instance, the Telfair Museums in Savannah, Georgia, holds his portrait of Gari Melchers' wife, Corinne Mackall Melchers.

The Brooklyn Museum and other institutions with collections of early 20th-century American and European art may also have examples.

Auction Records and Market Presence:

Henry Caro-Delvaille's works appear with moderate frequency on the international art market, handled by major auction houses like Sotheby's, Christie's, and Bonhams, as well as specialized French auctioneers.

Value Drivers: The value of his paintings at auction typically depends on several factors:

Subject Matter: His elegant nudes and sophisticated society portraits tend to be the most sought after and command higher prices. Genre scenes and less glamorous portraits may achieve more modest sums.

Period: Works from his peak Parisian period (roughly 1900-1914) are often highly valued.

Size and Condition: Larger, well-preserved canvases generally fetch better prices.

Provenance: A strong history of ownership, especially if linked to notable collections or exhibitions, can enhance value.

Artistic Quality: The finesse of execution, vibrancy of color, and overall aesthetic appeal are crucial.

Price Range: Prices for his oil paintings can range from a few thousand dollars for smaller studies or less significant works to tens of thousands, and occasionally over one hundred thousand dollars, for major exhibition pieces or particularly attractive nudes and portraits. For example, a large, appealing nude or a significant society portrait could achieve prices in the $30,000 to $80,000 range, with exceptional pieces potentially exceeding this. Drawings and smaller works are more accessible.

The market for Caro-Delvaille's art benefits from the broader interest in Belle Époque and academic-realist painting of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Collectors who appreciate technical skill, elegant subject matter, and a connection to this historical period find his work appealing. While not reaching the stratospheric prices of some of his more famous contemporaries, his market is stable, supported by a consistent demand from private collectors and dealers specializing in this era.

Scholarly Perspectives and Ongoing Research

Academic evaluation of Henry Caro-Delvaille has evolved over time. During his lifetime and in the immediately succeeding decades, he was a recognized and respected figure, particularly within the circles that valued academic skill and elegant representation. His Salon successes, medals, and prominent commissions in both France and the United States attest to his contemporary standing. Critics of the era often praised his refined technique, his harmonious color palettes, and his ability to capture the grace and intimacy of his subjects, especially in his depictions of women.

However, with the overwhelming ascendancy of Modernism in the mid-20th century, artists like Caro-Delvaille, who were perceived as more traditional or academic, were often relegated to the footnotes of art history. The dominant narrative focused on the avant-garde innovators who broke radically with past conventions – figures like Picasso, Matisse, or Marcel Duchamp. Artists who continued to work in figurative styles, even with the sophistication of Caro-Delvaille, were sometimes dismissed as retardataire or merely fashionable.

The late 20th and early 21st centuries have witnessed a significant reassessment of this period. Art historians have increasingly turned their attention to artists and movements previously overshadowed by Modernism. This has led to a renewed interest in academic art, Salon painting, Symbolism, and various forms of realism and figuration from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Within this broader scholarly trend, Henry Caro-Delvaille's work has found fresh appreciation.

Current Research and Evaluation:

Technical Skill and Aesthetics: Scholars now more readily acknowledge his considerable technical abilities, his mastery of draftsmanship, and his sophisticated use of color and composition. His work is studied for its aesthetic qualities, its elegance, and its embodiment of Belle Époque sensibilities.

Social and Cultural Context: His paintings, particularly his portraits and genre scenes, are valued as documents of a specific social milieu – the affluent bourgeoisie and aristocracy of Paris and New York. They offer insights into the tastes, lifestyles, and self-perception of this class.

Thematic Studies: His focus on the female nude is a subject of ongoing interest, examined within the context of evolving representations of women, intimacy, and sensuality in art. His nudes are often compared to those of contemporaries like Anders Zorn (1860-1920) or Paul César Helleu (1859-1927) for their modern yet elegant approach.

Transatlantic Career: His successful career on both sides of the Atlantic makes him an interesting case study in artistic migration and the cultural exchange between Europe and America in the early 20th century.

Place in Art History: While not considered a revolutionary figure, Caro-Delvaille is increasingly seen as an important representative of a significant strand of early 20th-century art that maintained a commitment to beauty, craftsmanship, and figuration, even as other artists pursued more radical paths. He is recognized for skillfully blending academic tradition with a more modern, intimate sensibility.

Research on Caro-Delvaille may appear in scholarly articles focusing on Salon painting, portraiture of the era, French art of the Belle Époque, or American society portraiture. Exhibition catalogues accompanying retrospectives or thematic shows that include his work are also important sources of scholarship. While a comprehensive, definitive monograph or catalogue raisonné might still be a desideratum for fully cementing his scholarly profile, his inclusion in museum collections and the ongoing interest in his period ensure that his contributions continue to be studied and appreciated. His work serves as a reminder of the diversity and richness of artistic production during a complex period of transition in art history.