Antoine Calbet stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in French art during the vibrant and transformative period spanning the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Active during the Belle Époque, an era characterized by artistic innovation, societal change, and a particular Parisian joie de vivre, Calbet carved a distinct niche for himself. He was a prolific painter, watercolorist, illustrator, and decorative artist, celebrated in his time for his technical skill, his appealing subject matter—especially his depictions of the female form—and his contributions to both the esteemed Paris Salon and the burgeoning world of published illustration. While perhaps not as revolutionary as the Impressionists or Post-Impressionists who were his contemporaries, Calbet's work offers a fascinating window into the tastes and sensibilities of his time, skillfully blending academic tradition with a modern, sensual appeal.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Antoine Calbet was born in 1860 in Engayrac, a small commune in the Lot-et-Garonne department of southwestern France. His origins were rooted in the regional bourgeoisie; his father, Jean-Baptiste Calbet, was a landowner, and his mother was Marie Singlande. This background likely provided him with the stability and means to pursue an artistic education. His initial training took place not in Paris, but in the southern city of Montpellier, known for its own rich artistic heritage and home to the Musée Fabre, which housed significant collections that could have inspired the young artist.

Seeking to further his ambitions, Calbet eventually made his way to Paris, the undisputed center of the art world. There, he enrolled in the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the bastion of academic art training in France. His tutelage under two notable figures of the academic establishment was crucial in shaping his technical foundation. He studied with Alexandre Cabanel, one of the most famous and influential academic painters of the Second Empire and early Third Republic. Cabanel, renowned for historical, mythological, and biblical scenes executed with a smooth, highly finished technique—epitomized by his wildly successful The Birth of Venus (1863)—undoubtedly instilled in Calbet a mastery of drawing, composition, and the idealized rendering of the human form.

Calbet also studied under Édouard Antoine Marsal, a painter perhaps less famous than Cabanel today but respected in his time, particularly for portraits and genre scenes. Marsal, also rooted in the academic tradition, would have reinforced the principles of careful observation and polished execution. This rigorous training provided Calbet with the technical arsenal necessary to succeed within the established art system of the era, particularly the all-important Paris Salon. It placed him firmly within the lineage of academic painting, even as new, more radical movements like Impressionism, spearheaded by artists such as Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, were challenging its dominance.

Emergence onto the Parisian Art Scene

Calbet made his official debut on the competitive Parisian art stage in 1880, exhibiting for the first time at the Salon des Artistes Français. The Salon was then the primary venue for artists to gain recognition, attract patrons, and build their careers. Acceptance into the Salon was a significant achievement, and Calbet would continue to exhibit there regularly for decades, until 1940. His early submissions quickly garnered attention, suggesting that his blend of academic polish and appealing subject matter resonated with both the jury and the public.

His consistent presence at the Salon indicates a successful navigation of the official art world. He became a member of the Société des Artistes Français, the organization running the Salon after its split from government control. This affiliation further cemented his position within the mainstream art community. His work, particularly his skillful and often sensual depictions of women and pleasant genre scenes, found favor with the public taste, which, while increasingly exposed to Impressionism and other modern styles, still held a strong appreciation for well-executed, easily understandable, and aesthetically pleasing art. Calbet's ability to satisfy this demand contributed significantly to his growing reputation.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

Antoine Calbet's artistic style is best understood as a skillful synthesis of his academic training and an awareness of contemporary trends, particularly a certain lightness and sensuality associated with the Belle Époque. He did not embrace the radical optical experiments of the Impressionists like Monet or Renoir, nor the structural explorations of Post-Impressionists like Cézanne. Instead, he adapted elements that suited his temperament and subject matter, creating a style that was both accomplished and accessible.

His technical foundation, inherited from Cabanel and Marsal, is evident in his confident drawing, his smooth modeling of forms, especially flesh, and his balanced compositions. However, his work often possesses a warmth and vibrancy that distinguishes it from stricter academicism. His palette could be rich and colorful, and his brushwork, particularly in watercolors and less formal oil sketches, could exhibit a degree of looseness and spontaneity. He was particularly adept at rendering textures, from shimmering silks to soft skin, contributing to the tactile appeal of his paintings.

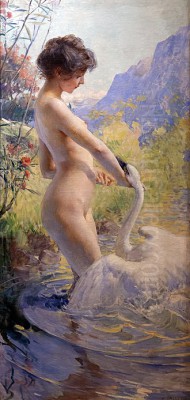

Thematically, Calbet is most renowned for his depictions of the female nude. In an era that saw diverse approaches to the subject, from the confrontational realism of Édouard Manet's Olympia to the voyeuristic intimacy of Edgar Degas's bathers and the idealized allegories of academic contemporaries like William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Calbet found his own popular niche. His nudes are typically youthful, graceful, and imbued with a gentle eroticism. They often appear in mythological guises (like Daphnis et Chloe), allegorical settings, or intimate boudoir scenes. While sensual and sometimes flirtatious, they generally avoid the controversial or overtly provocative, striking a balance that appealed to mainstream collectors and the Salon public.

Beyond the nude, Calbet also painted landscapes, often imbued with a soft, atmospheric quality, and genre scenes depicting elegant social life or moments of quiet domesticity. His versatility extended to portraiture as well. Across his subjects, a consistent characteristic is a sense of charm, elegance, and technical finesse. He mastered watercolor, a medium well-suited to capturing fleeting effects of light and achieving delicate tonal transitions, and his works in this medium were highly regarded.

Masterworks and Notable Commissions

While Calbet produced numerous easel paintings and watercolors throughout his long career, some of his most prominent and enduring works were large-scale decorative commissions. These projects demonstrate his ability to work on an ambitious scale and integrate his art into architectural settings, a skill highly valued during the Belle Époque's flourishing of public and private decoration.

Perhaps his most famous commission was for Le Train Bleu, the opulent buffet restaurant inside the Gare de Lyon railway station in Paris. Inaugurated in 1901, the restaurant was designed as a showpiece of Belle Époque luxury, celebrating the expansion of the PLM railway network. Calbet was one of several prominent artists commissioned to decorate its lavish interiors. He contributed paintings representing cities and regions served by the railway, integrating his characteristic style into the overall decorative scheme. Working alongside artists like Albert Maignan, Henri Gervex, and others, Calbet helped create one of the most iconic Belle Époque interiors still extant today.

Calbet also undertook other significant decorative projects. He painted decorations for the municipal theater in Annecy, including ceiling paintings, showcasing his ability to handle complex allegorical or historical compositions on a grand scale. He is also credited with decorative work in Dijon and potentially for a restaurant associated with the Paris Opera. These commissions highlight his reputation as a reliable and skilled decorative painter, capable of enhancing prestigious public spaces with his elegant and accessible style.

Among his easel paintings, Transparences, now housed in the ARC Museum in Cambrai, is often cited as a representative work, likely showcasing his skill in rendering light, texture, and the female form. His mythological painting Daphnis et Chloe reflects his engagement with classical themes, a staple of academic tradition but rendered with his characteristic charm. Numerous other Salon paintings, watercolors, and drawings further attest to his prolific output and consistent quality.

The Illustrator's Craft

Beyond his work as a painter, Antoine Calbet was a highly successful and sought-after illustrator. The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries witnessed an explosion in illustrated books and periodicals, fueled by advances in printing technology and a growing literate public hungry for visual content. Calbet excelled in this field, bringing his artistic sensibility and technical skill to the printed page.

He provided illustrations for numerous literary works, collaborating with major publishers and authors. His delicate and often sensual style proved particularly well-suited to illustrating contemporary novels, classical texts, and poetry. Notable examples include his illustrations for editions of Homer's Odyssey, Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Confessions, and works by popular French authors like Émile Zola (including Madame Neige, possibly related to the work sometimes cited as La Sandale Ailée) and Guy de Maupassant (Belles Amies). He also illustrated fables, such as those by La Fontaine, demonstrating his versatility across different literary genres.

His illustrations often appeared in magazines and journals as well. He contributed to publications like Bibliothèque moderne illustrée, working alongside other popular illustrators of the day such as Leonetto Cappiello, known for his bold poster designs, and Marcel Capy. This work placed him at the heart of the commercial art world, making his style familiar to a broad audience beyond the confines of the Salon. Calbet's illustrations typically complemented the text with grace and sensitivity, capturing the mood and key moments of the narrative, often focusing on elegant figures and atmospheric settings. His success in this field contributed significantly to his income and reputation, though it also sometimes led to discussions about the perceived hierarchy between "fine art" painting and the more commercial art of illustration.

Navigating the Art World: Connections and Context

Antoine Calbet's career unfolded within a complex and dynamic art world. His success was built not only on his talent but also on his ability to navigate the institutions, networks, and tastes of his time. His training under Cabanel and Marsal provided him with impeccable academic credentials and connections within the established art system. His regular participation and eventual membership in the Société des Artistes Français solidified his standing within the Salon structure.

He also benefited from influential connections outside the immediate art world. A significant relationship was his friendship with Armand Fallières, a politician also hailing from Lot-et-Garonne who served as President of France from 1906 to 1913. Calbet reportedly designed menus for official functions hosted by Fallières, a task that, while seemingly minor, would have placed his name and artistry before the highest echelons of French society and government, undoubtedly boosting his prestige and potentially leading to further commissions or patronage.

While operating primarily within the Salon system, Calbet was aware of the broader artistic landscape. He competed, in effect, with other artists specializing in similar genres. His popular nudes occupied a space alongside those of academic giants like Bouguereau, but also existed in dialogue with the more modern approaches of Degas or Pierre-Auguste Renoir, whose later works also celebrated sensuous female forms. His decorative work placed him alongside other successful muralists like Gervex and Maignan.

His reputation extended beyond France. The mention of international artists like Gustav Klimt (Austria) and Joaquín Sorolla (Spain) taking notice of his work suggests he achieved a degree of recognition on the European stage. This was further confirmed by his reception of awards at international expositions. He managed to maintain a successful career by skillfully blending traditional techniques with subjects and a style that resonated with the prevailing tastes of the Belle Époque bourgeoisie, while also engaging actively in the lucrative field of illustration.

Reception, Recognition, and Legacy

Antoine Calbet enjoyed considerable success and recognition during his lifetime. His popularity with the public was matched by official accolades. He received medals at the Paris Salon in consecutive years (1891, 1892, 1893), indicating consistent approval from the Salon juries. A significant honor was the Silver Medal awarded at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) held in Paris in 1900, a major international event showcasing achievements in arts, science, and industry. Furthermore, he was appointed a Chevalier (Knight) of the Legion of Honour, France's highest order of merit, acknowledging his contributions to French art and culture.

His works were acquired by state institutions and museums, ensuring their preservation and public access. Paintings by Calbet entered the collections of the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris (whose collections of living artists were later dispersed, with some potentially ending up in the Musée d'Orsay or other national museums), the Musée des Augustins in Toulouse, and the museum in Cambrai, among others. This official recognition solidified his status as an established and respected artist.

However, Calbet's legacy is somewhat complex. While highly successful in his time, his reputation has perhaps been overshadowed in art historical narratives by the more revolutionary figures of modernism. His adherence to a more traditional, albeit updated, aesthetic meant he was not part of the avant-garde movements that came to dominate twentieth-century art history. The very qualities that made him popular—elegance, charm, sensuality, technical polish—could sometimes be viewed by later critics as lacking the depth or formal innovation of his modernist contemporaries.

Furthermore, his significant activity as an illustrator sometimes led to his work being categorized within the applied arts, historically considered secondary to the "fine arts" of painting and sculpture. While illustration enjoyed a golden age during his lifetime, this distinction could subtly affect an artist's long-term canonical status. Nevertheless, Calbet remains an important figure for understanding the mainstream artistic tastes of the Belle Époque, particularly the enduring appeal of the idealized female form, decorative elegance, and skilled narrative illustration.

Later Years and Conclusion

Antoine Calbet continued to work and exhibit well into the twentieth century, remaining active at the Salon des Artistes Français until 1940. He lived through a period of immense social and political upheaval, including the First World War and the changing cultural landscape of the interwar years. His style, rooted in the aesthetics of the late nineteenth century, likely appeared increasingly traditional as new movements like Cubism, Surrealism, and abstraction emerged.

He passed away in Paris in 1944, at the advanced age of 84, during the tumultuous final year of the German occupation of France in World War II. His death marked the end of a long and productive career that spanned over six decades.

In conclusion, Antoine Calbet was a quintessential artist of the French Belle Époque. Trained in the academic tradition under masters like Cabanel, he developed a distinctive and popular style characterized by technical finesse, sensual depictions of the female form, and an elegant charm. He achieved significant success within the official Salon system, secured prestigious decorative commissions like Le Train Bleu, and became a prolific and sought-after illustrator for major literary works. While perhaps not a radical innovator, his art perfectly captured a specific sensibility of his era, balancing tradition and modernity, refinement and sensuality. His work continues to be appreciated for its beauty, skill, and as a valuable reflection of the artistic culture of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century France. He remains a testament to the enduring appeal of academic grace infused with the vibrant spirit of his time.