Almery Lobel-Riche stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in early 20th-century French art. Born on March 5, 1880, in Geneva, Switzerland, to parents of French heritage, he would become a quintessential Parisian artist, capturing the spirit and allure of the Belle Époque and the subsequent interwar period. His life, spanning from 1880 to his death in 1950, was dedicated to the arts, primarily as a printmaker, illustrator, and engraver, with a particular mastery of etching. His work provides a fascinating window into the society, aesthetics, and literary currents of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Almery, whose full name was Alméry Lucien Riche, though he often signed his works Lobel-Riche, embarked on his artistic journey with formal training. He initially studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Montpellier, a city in the South of France with a rich cultural history. This foundational education would have provided him with the classical drawing skills essential for any aspiring artist of the period.

Seeking to further hone his talents and immerse himself in the vibrant heart of the European art world, Lobel-Riche moved to Paris. There, he continued his studies at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. Crucially, he became a pupil of Léon Bonnat (1833-1922), a highly respected academic painter known for his portraits of prominent figures and his adherence to traditional techniques. Bonnat's tutelage would have emphasized rigorous draftsmanship and a solid understanding of anatomy and composition, elements that are discernible even in Lobel-Riche's more stylized and evocative later works.

Emergence in the Parisian Art Scene

The turn of the century was a period of immense artistic innovation and social change in Paris. Lobel-Riche quickly found his footing in this dynamic environment. A significant early milestone in his career occurred in 1895 when he successfully submitted his first drawing to Le Rire, a popular satirical weekly magazine. This publication was a notable venue for illustrators and caricaturists, featuring works by artists like Théophile Steinlen (1859-1923) and Jean-Louis Forain (1852-1931), who also captured Parisian life with wit and keen observation. This early success signaled Lobel-Riche's entry into the professional art world and hinted at his burgeoning talent for visual storytelling.

His reputation grew as he began to exhibit his works, primarily etchings and drypoints. He became known for his depictions of the Parisian elite, the fashionable women of the Belle Époque, and the more clandestine world of the demimonde. His art often explored themes of femininity, sensuality, and the sophisticated, sometimes decadent, atmosphere of the era. He was not alone in this pursuit; artists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) had famously chronicled the nightlife of Montmartre, while society portraitists like Giovanni Boldini (1842-1931) captured the elegance of the upper classes. Lobel-Riche carved his own niche within this milieu.

Master of Etching and Drypoint

Lobel-Riche's primary medium was intaglio printmaking, particularly etching and drypoint. Etching involves incising a design into a metal plate (usually copper) covered with an acid-resistant ground, then immersing the plate in acid, which "bites" into the exposed lines. Drypoint, by contrast, involves scratching directly into the plate with a sharp needle, creating a burr that yields a soft, velvety line when printed. Lobel-Riche often combined these techniques to achieve rich tonal variations and exquisite detail.

His technical skill was remarkable. He possessed an ability to render textures, from the sheen of silk to the softness of skin, with remarkable fidelity. His use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) was masterful, creating a sense of drama and intimacy in his compositions. This technical prowess allowed him to imbue his subjects with a palpable presence, whether they were languid nudes, elegantly attired society ladies, or characters from literature. His command of the medium placed him in the company of other notable printmakers of the era, such as Anders Zorn (1860-1920), a Swedish artist also renowned for his etchings of nudes and portraits, and James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), whose atmospheric etchings had a profound impact on printmaking.

Themes: The Parisian Woman and the Belle Époque

The central theme in much of Lobel-Riche's oeuvre was the woman of Paris. He depicted her in various guises: the sophisticated lady of leisure, the alluring courtesan, the pensive nude. His works often exude an air of luxury and sensuality, characteristic of the Belle Époque's fascination with beauty and pleasure. This period, roughly from the 1870s to the outbreak of World War I in 1914, was a time of optimism, peace, and artistic flourishing in Paris, and Lobel-Riche's art reflects its particular social ambiance.

His female figures are rarely passive objects of gaze; they often possess a knowing confidence, a subtle power that engages the viewer. He was adept at capturing nuanced expressions and body language, suggesting complex inner lives. While some of his nudes are overtly sensual, they are typically rendered with an elegance that avoids vulgarity, aligning more with the refined eroticism seen in the work of artists like Félicien Rops (1833-1898), albeit often with a softer touch than the sometimes more overtly decadent Belgian master. The influence of Symbolism can be detected in the evocative, dreamlike quality of some of his pieces, hinting at deeper psychological states or allegorical meanings, a movement championed by artists like Gustave Moreau (1826-1898) and Odilon Redon (1840-1916).

Illustrative Genius: Collaborations with Literary Giants

Beyond his independent prints, Lobel-Riche was a highly sought-after illustrator of books. This aspect of his career brought his art to a wider audience and connected him with the literary currents of his time. He created illustrations for works by a remarkable roster of authors, demonstrating his versatility in interpreting diverse literary styles.

Among the authors whose books he illustrated were:

Oscar Wilde (1854-1900): The wit and aestheticism of Wilde's writing found a sympathetic visual counterpart in Lobel-Riche's elegant style.

Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867): Illustrating Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil) would have been a significant undertaking, requiring an artist capable of conveying the poems' complex themes of beauty, decay, and urban ennui. Lobel-Riche's interpretations, created in the 1920s and 30s, are considered important contributions.

Pierre Loti (1850-1923): Loti's exotic tales and romantic narratives provided rich material for Lobel-Riche's evocative imagery.

Émile Zola (1840-1902): The naturalism of Zola's novels, often depicting the harsher realities of Parisian life, might seem a contrast to Lobel-Riche's more typically elegant subjects, but his skill allowed him to adapt.

Guy de Maupassant (1850-1893): He notably illustrated Maupassant's La Maison Tellier (The Tellier House), a story about a provincial brothel, capturing the characters and atmosphere with sensitivity and insight.

Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849): A particularly notable project was his illustrations for Vingt histoires extraordinaires (Twenty Extraordinary Tales) by Poe, translated by Baudelaire. This edition, published by Le Livre de Plantin in 1927, featured Lobel-Riche's etchings and was a testament to his ability to capture the macabre and mysterious. A copy of this edition was sold at a Sotheby's auction in New York in 1976, indicating its lasting value.

His work as an illustrator was not merely decorative; it was interpretative, adding a visual dimension that enhanced the reader's experience. This placed him in a tradition of great French book illustrators, a field that also included artists like Gustave Doré (1832-1883) from an earlier generation, and contemporaries who also engaged in deluxe illustrated editions.

Notable Works and Artistic Style

One of Lobel-Riche's most celebrated series of etchings is Études de Filles [L’Atlantide] (Studies of Girls [Atlantis]). This collection showcases his mastery in depicting the female form, characterized by fine, delicate lines, a sophisticated interplay of light and shadow, and an atmosphere of intimate sensuality. The works in this series are prime examples of his ability to convey both elegance and a subtle eroticism. The reference to "L'Atlantide" might allude to the mythical lost city, perhaps suggesting a timeless, idealized, or mysterious quality to the women portrayed.

His artistic style, while rooted in academic training, absorbed contemporary influences. The elegance and elongated forms in some of his figures might show a subtle nod to Art Nouveau sensibilities, though he was not strictly an Art Nouveau artist like Alphonse Mucha (1860-1939). The atmospheric qualities and focus on light in his prints also suggest an awareness of Impressionism, particularly the way artists like Edgar Degas (1834-1917) used printmaking to explore effects of light and form. However, Lobel-Riche's meticulous detail and often more polished finish distinguish him from the core Impressionists. He often favored a palette of rich blacks, browns, and sepias in his prints, sometimes using sanguine or ochre tones to add warmth and depth.

Beyond Prints: Paintings and Other Media

While primarily known as a printmaker, Lobel-Riche also worked in other media, including oil painting. One example mentioned is the oil painting The Agave. This suggests an interest in natural forms and perhaps a broader artistic exploration beyond his typical figural subjects. The agave plant, with its strong, sculptural form, would have offered a different kind of aesthetic challenge. His training under Bonnat would certainly have equipped him with the skills for oil painting, though his prints remain his most recognized contribution.

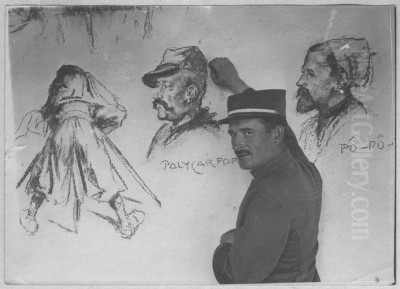

His versatility extended to drawing, which formed the foundation of all his work. His drawings, whether preparatory sketches for prints or standalone pieces, would have demonstrated the same keen observation and skilled draftsmanship evident in his etchings.

Later Career and Legacy

Almery Lobel-Riche continued to work and exhibit throughout the first half of the 20th century. He navigated the shifting artistic landscape that saw the rise of Cubism, Fauvism, Surrealism, and other avant-garde movements. While he remained largely faithful to his own figurative and elegant style, his work continued to find an appreciative audience, particularly among collectors of fine prints and illustrated books.

He passed away in 1950, at the age of 70. By this time, the art world had undergone profound transformations. However, Lobel-Riche's legacy endures, primarily through his exquisite etchings and his contributions to the art of book illustration. His work is held in various public and private collections and continues to appear at auctions, attesting to its enduring appeal.

His art provides a specific lens on the Belle Époque and interwar Paris, focusing on a world of elegance, intimacy, and literary sophistication. He was a chronicler of a certain type of Parisian femininity, rendered with technical brilliance and a distinctive aesthetic sensibility. He stands alongside other artists who captured the multifaceted spirit of Paris, such as Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947) and Édouard Vuillard (1868-1940), who depicted intimate domestic scenes, or Kees van Dongen (1877-1968), whose bold Fauvist portraits also captured the modern woman, albeit in a very different style.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Parisian Elegance

Almery Lobel-Riche was an artist deeply embedded in the cultural fabric of Paris during a transformative period. His mastery of etching and drypoint allowed him to create images of enduring beauty and allure, capturing the sophisticated, and sometimes decadent, spirit of the Belle Époque and beyond. His depictions of women, whether as society figures or as subjects of intimate study, are characterized by technical finesse and a subtle psychological depth.

Through his extensive work as an illustrator, he engaged with some of the most important literary voices of his own and preceding generations, creating a visual dialogue that enriched both the texts and his own artistic output. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his avant-garde contemporaries, Lobel-Riche's dedication to craftsmanship and his distinctive vision of Parisian elegance and femininity have secured him a lasting place in the history of French printmaking and illustration. His works continue to charm and fascinate, offering a glimpse into a bygone era through the eyes of a skilled and sensitive artist.