Henry Chapman Ford (1828-1894) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in nineteenth-century American art. His multifaceted career as a landscape painter, etcher, illustrator, and educator, particularly his dedicated efforts to document the California Missions, has left an indelible mark on the cultural and historical understanding of the American West. Ford was not merely an artist capturing picturesque scenes; he was an active participant in the preservation of history and a foundational figure in the burgeoning art communities of both Chicago and Santa Barbara.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Livonia, New York, in 1828, Henry Chapman Ford's early artistic inclinations led him to seek formal training in Europe, a common path for ambitious American artists of his generation. Between 1857 and 1860, he immersed himself in the art scenes of Paris and Florence. In Paris, he would have been exposed to the waning influence of Neoclassicism and Romanticism, and the rising tide of Realism, particularly the Barbizon School painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Jean-François Millet, whose dedication to landscape and rural life was revolutionizing art. Florence, with its rich Renaissance heritage, would have offered profound lessons in drawing, composition, and the classical tradition. This European sojourn equipped Ford with a solid technical foundation and a broadened artistic perspective.

Upon his return to the United States, the nation was on the brink of the Civil War. Ford contributed to the war effort as a news illustrator, a role that required keen observation and rapid execution, skills that would serve him well in his later landscape and architectural work. Artists like Winslow Homer also began their careers as illustrators during this period, capturing the realities of conflict for a public hungry for images. However, Ford's service was cut short; after only a year, he was discharged due to physical disability. This pivotal moment redirected his path towards a dedicated career in fine arts.

The Chicago Years: A Pioneer in a Growing City

Following his military service, Henry Chapman Ford moved to Chicago, Illinois. In this rapidly expanding Midwestern metropolis, he distinguished himself as the city's first professional landscape painter. The American landscape was a dominant theme in art at this time, with the Hudson River School artists such as Thomas Cole, Asher B. Durand, and Frederic Edwin Church having already established a grand tradition of depicting the nation's natural wonders. Ford brought his skills to bear on the Illinois scenery, contributing to the visual identity of the region.

His commitment to the arts in Chicago extended beyond his personal practice. Ford played an instrumental role in founding the Chicago Academy of Design in 1866, which would later evolve into the renowned School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He served as its president for several years, guiding its early development and fostering an environment for artistic education and appreciation in the city. Unfortunately, a significant portion of his early work, likely including many of his Chicago-era landscapes, was tragically lost in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, which also destroyed the Academy's building. This loss was a considerable setback, but Ford's resilience would see him rebuild his career.

A New Chapter in California: Health and Heritage

The harsh Midwestern climate eventually took a toll on Ford's health. Seeking a more salubrious environment, he moved to Colorado in 1875. His artistic pursuits continued, and he likely captured the dramatic mountain landscapes of the Rockies, a region also famously painted by artists like Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran. However, his stay in Colorado was relatively brief. By the early 1880s, Ford had relocated again, this time to Santa Barbara, California. This move would prove to be the most significant for his artistic legacy.

Santa Barbara, with its mild climate, stunning coastal scenery, and rich Spanish colonial history, provided Ford with abundant inspiration. He quickly established himself within the community, not only as an artist but also as a keen observer of the natural world and a proponent of civic improvement. His studio became a local attraction, showcasing not only his paintings and etchings but also his collections of shells, fossils, and archaeological artifacts gathered from his explorations of the coast and nearby islands.

The California Missions: A Monumental Undertaking

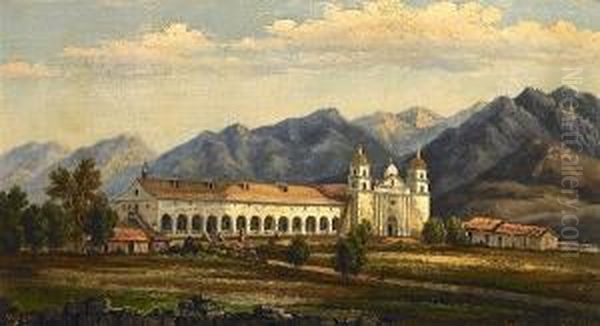

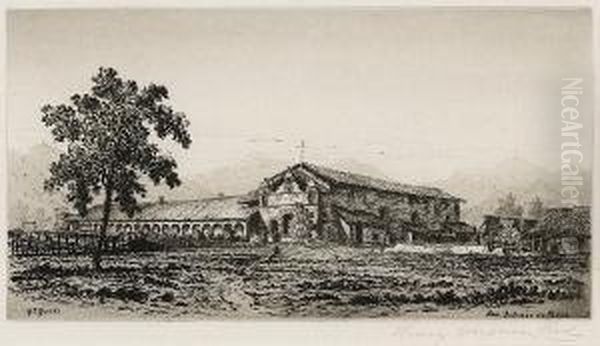

It was in California that Henry Chapman Ford embarked on the project for which he is best known: the comprehensive documentation of all twenty-one Franciscan missions. These historic structures, established between 1769 and 1823, were in varying states of repair, many crumbling into ruin. Ford recognized their historical and architectural significance and set out to record them before they were lost entirely or irrevocably altered.

Over several years, often traveling by horse or carriage to remote locations, Ford meticulously sketched each mission on site. These field studies formed the basis for a remarkable series of works executed in watercolors, oil paintings, and, most notably, etchings. His approach was largely documentary, aiming for accuracy in depicting the architectural features and the surrounding landscapes. This dedication to faithful representation provides invaluable historical records of the missions' appearance in the late nineteenth century.

His portfolio, "Etchings of the Franciscan Missions of California," published in 1883, and a later set in 1891, brought these iconic structures to a wider audience. Works such as his depictions of Mission San Juan Capistrano, Mission Santa Barbara, Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo, "San Francisco Solano," and the "Asistencia de San Antonio de Pala" are prime examples of his skill and dedication. These etchings were not merely artistic endeavors; they played a crucial role in fostering a renewed appreciation for California's Spanish colonial heritage.

The widespread dissemination of Ford's mission images contributed significantly to the burgeoning Mission Revival architectural style and the broader "Mission Style" arts and crafts movement that gained popularity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His work, alongside that of other artists and writers, helped to romanticize the mission era and spurred public interest in the preservation and restoration of these historic landmarks. Indeed, Ford's visual records often served as important references for later restoration efforts.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Henry Chapman Ford's artistic style was rooted in the realist tradition of the 19th century. His European training instilled in him a respect for accurate drawing and careful composition. As a landscape painter, his work shares affinities with the detailed naturalism of the Hudson River School, though his focus was often more intimate and less overtly grandiose than, for example, the epic canvases of Bierstadt or Church. He possessed a keen eye for the effects of light and atmosphere, evident in his oil paintings and watercolors.

His landscape paintings, such as the noted "West Beach" in Santa Barbara, capture the specific character of the California coast and its unique flora. He often ventured into the backcountry, creating plein-air sketches that he would later develop into finished paintings in his studio. This practice was common among landscape artists of his time, including figures like Sanford Robinson Gifford and John Frederick Kensett, who also balanced direct observation with studio refinement.

Ford's proficiency as an etcher was particularly significant. The Etching Revival was well underway in Europe and America during the latter half of the 19th century, with artists like James Abbott McNeill Whistler and Seymour Haden popularizing the medium. While Ford's etchings were primarily documentary rather than expressive in the manner of Whistler, they demonstrated considerable technical skill and an ability to convey architectural detail and texture effectively. His mission etchings, in particular, are characterized by their clarity and precision.

Beyond the Missions: Yosemite and Other Subjects

While the California Missions were a central focus, Ford's artistic interests were broader. In 1878, he journeyed to Yosemite Valley, one of the great touchstones for American landscape painters. There, he created works such as a view from Glacier Point, adding his interpretations to a landscape famously depicted by artists like Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Hill, and William Keith. His Yosemite paintings would have engaged with the established iconography of this natural wonder, likely emphasizing its sublime beauty and geological grandeur.

His body of work also includes numerous depictions of the Santa Barbara coastline, its oak-studded hills, and its developing townscape. These paintings and sketches provide a valuable visual record of the region before the extensive development of the 20th century. He continued to paint and exhibit throughout the 1880s and into the early 1890s, always demonstrating a profound connection to the natural environment and a fascination with the historical layers of the California landscape.

Community Engagement and Legacy in Santa Barbara

Henry Chapman Ford was more than just a resident artist in Santa Barbara; he was an active and influential community member. He co-founded the Santa Barbara Society of Natural History (now the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History) and the local Horticultural Society, reflecting his deep interest in the region's flora, fauna, and geology. His advocacy extended to civic improvements; he reportedly offered suggestions for the planting of trees and even the architectural style of public amenities, demonstrating a holistic vision for the aesthetic and environmental quality of his adopted city.

As Santa Barbara's first resident professional artist of note, Ford helped to lay the groundwork for the city's development as a significant arts center. His presence and work attracted other artists and contributed to a growing cultural sophistication. His studio was a place of learning, as he also taught painting, passing on his knowledge and skills to a new generation. Artists who followed in the California landscape tradition, such as Guy Rose or William Wendt, though of a later, more Impressionist-influenced generation, benefited from the artistic appreciation Ford helped cultivate.

Anecdotes and Personal Glimpses

Anecdotes from Ford's life offer a more personal view of the artist. His dedication to his craft is evident in his willingness to travel to remote mission sites, often under challenging conditions. The fact that his wife sometimes accompanied him on these sketching expeditions, occasionally with a pet hawk reportedly hatched from a chicken's nest, adds a touch of charming eccentricity and highlights a shared adventurous spirit.

His studio in Santa Barbara, filled with his artwork alongside his natural history collections, suggests a man of broad intellectual curiosity, a common trait among many educated individuals of the Victorian era. His participation in exhibitions, including the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago where he showed his mission etchings, indicates his desire to share his work and his vision with a national audience. This exposition was a major cultural event, featuring works by prominent American artists like Mary Cassatt and Thomas Eakins.

Historical Evaluation and Enduring Influence

Henry Chapman Ford's primary artistic achievement lies in his comprehensive visual documentation of the California Missions. These works are invaluable not only as art but also as historical records. They captured a critical moment in the life of these structures, preserving their appearance for posterity and significantly contributing to the movement for their preservation and the broader Mission Revival. His dedication to this project, undertaken with considerable personal effort and expense, was remarkable.

His landscape paintings, while perhaps less widely known than his mission series, demonstrate a sensitive engagement with the California environment. They contribute to the rich tradition of American landscape painting, reflecting both the prevailing aesthetic sensibilities of his time and a personal connection to the places he depicted.

As a community leader in Santa Barbara, Ford's influence extended beyond the canvas. His efforts in establishing cultural and scientific institutions helped to shape the city's character and contributed to its reputation as a center for art and natural beauty. He is remembered as a pioneering figure who not only recorded the visual aspects of his adopted home but actively worked to enhance its cultural and civic life.

Henry Chapman Ford passed away in Santa Barbara in 1894, at the age of 66. His legacy endures through his extensive body of work, which continues to be studied by art historians and cherished by those interested in California's history and heritage. His paintings and etchings are held in numerous museum collections, ensuring that his vision of California's past and its natural beauty remains accessible to future generations. He was a man of his time, driven by the 19th-century passion for exploration, documentation, and the celebration of both natural and historical wonders, leaving behind a rich artistic and cultural inheritance.