John Edward Borein stands as a pivotal figure in the art of the American West, an artist whose life and work were inextricably linked to the cowboy culture and landscapes he so meticulously documented. Born in San Leandro, California, in 1872, Borein entered a world where the echoes of the Spanish vaquero tradition still resonated and the era of the great cattle drives was nearing its twilight. His unique contribution lies not just in his technical skill across various mediums, but in the profound authenticity born from firsthand experience, earning him the title "cowboy artist" in the truest sense. Unlike many contemporaries who observed the West, Borein lived it, and this lived experience permeates every line of his etchings, every wash of his watercolors.

His artistic journey began not in formal academies but on the dusty plains and rolling hills of California. Growing up near the San Francisco Bay Area, in a town steeped in ranching heritage, Borein was surrounded by the subjects that would dominate his life's work. From the tender age of five, his innate talent for drawing horses, cattle, and the figures of cowboys became apparent, nurtured by his family. This early immersion provided a foundation of understanding that formal training alone could never replicate. He didn't just see the West; he felt its rhythms, understood its demands, and respected its inhabitants, both human and animal.

The Making of a Cowboy Artist

Borein's formal education in art was notably brief. While he did enroll at the San Francisco Art Association's School of Design (later the Mark Hopkins Institute of Art) around the age of 19, his tenure lasted perhaps only a month. There, he crossed paths with individuals who would become significant figures in Western art, including Maynard Dixon and Jimmy Swinnerton. However, the structured environment of the classroom held less appeal than the open range. Borein felt the call of the West more strongly than the lure of academic instruction.

He made a decisive choice: to leave school and embrace the life of a working cowboy. At seventeen, even before his brief stint in art school, he had begun working on ranches. Now, he fully committed, becoming a vaquero and traveling extensively. For nearly a decade, Borein rode the ranges, working cattle from the vast ranches of California up through Oregon and potentially Nevada, and south into Mexico. This period was not a detour from his art but an essential part of its development. He sketched constantly, capturing the life around him directly from the saddle or during quiet moments around the campfire, filling notebooks with observations that would fuel his later studio work.

This immersion provided an unparalleled education. He learned the anatomy of horses and cattle not just from observation but from working with them daily. He understood the specific gear of the vaquero, the nuances of roping techniques, the posture of a rider perfectly balanced on a moving horse. This intimate knowledge separated his work from that of artists who relied solely on models or photographs. Borein's cowboys were not generic figures; they were authentic representations of working men, depicted with an accuracy that fellow horsemen immediately recognized and respected. His travels across diverse landscapes, from California's coastal ranges to the deserts of the Southwest and the plains of Mexico, also broadened his visual vocabulary.

From Illustrator to Etcher: Finding His Voice

Around the turn of the century, Borein transitioned from full-time cowboy work towards a professional art career, though his connection to the West remained his anchor. He took a position as an illustrator for the San Francisco Call newspaper around 1900, honing his skills in drawing and composition under the pressure of deadlines. This experience likely refined his ability to tell a story visually and capture essential details quickly. During this time, he continued his travels, gathering sketches and experiences throughout the American Southwest and Mexico, constantly enriching his portfolio of Western subjects.

A significant turning point came in 1907 when Borein moved to New York City. This move was driven by a desire to further his artistic development, particularly in the medium of etching. While he briefly attended classes at the prestigious Art Students League, his primary focus was mastering the intricacies of printmaking. New York, then the center of the American art world, offered exposure to different techniques, artists, and markets. He associated with other illustrators and artists, potentially including figures connected to the Ashcan School or established illustrators like Harvey Dunn, though his core focus remained resolutely Western.

In New York, Borein dedicated himself to etching, quickly achieving a remarkable proficiency. He found the medium perfectly suited to his linear style and his desire for precise detail. Etching allowed him to translate the dynamic energy of his sketches into permanent, reproducible images. His skill did not go unnoticed. He held successful exhibitions in New York galleries in 1915 and 1917, establishing his reputation on a national level. Collectors began to appreciate the unique combination of authentic subject matter and technical finesse in his work. He was making a name for himself as a serious artist, not just an illustrator of Western scenes.

The Santa Barbara Years: Maturity and Mastery

Despite his success in the East, the call of California remained strong. In 1921, Edward Borein and his wife, Lucile, settled in Santa Barbara. This marked the beginning of the most settled and arguably most productive period of his career. Santa Barbara, with its own rich Spanish and Rancho history, provided a congenial atmosphere and proximity to the landscapes and culture he loved. He established a studio in the picturesque El Paseo complex, which quickly became a gathering place for artists, writers, and fellow enthusiasts of the West.

His Santa Barbara studio wasn't just a place to work; it was a gallery and a social hub. Here, Borein displayed his etchings, watercolors, and oil paintings, welcoming visitors and sharing his passion for Western heritage. He became an integral part of Santa Barbara's burgeoning art community, associating with artists like Carl Oscar Borg, DeWitt Parshall, and potentially encountering others drawn to the California light, such as Colin Campbell Cooper. He also dedicated time to teaching, sharing his knowledge and experience with students at the Santa Barbara School of the Arts.

During these years, Borein solidified his position as one of the preeminent artists of the American West. He continued to travel, making sketching trips to Arizona, New Mexico, and Mexico, ensuring his work remained fresh and grounded in direct observation. However, his Santa Barbara base provided the stability to refine his techniques and produce a significant body of work. His etchings reached their peak of technical brilliance, and his watercolors displayed a masterful handling of light and atmosphere, capturing the unique clarity of the California air. He became a celebrated local figure, respected for his artistry and his embodiment of the Western spirit.

Artistic Style: Authenticity in Line and Form

Edward Borein's artistic style is defined by its unwavering commitment to accuracy and authenticity, rendered primarily through a masterful command of line. Whether working in pencil, ink, watercolor, or the demanding medium of etching, his foundation was always strong draftsmanship. He possessed an innate ability to capture the form and movement of his subjects – particularly horses and riders – with remarkable economy and precision. His lines are clean, confident, and descriptive, conveying anatomical accuracy and dynamic energy simultaneously.

His experience as a working cowboy provided an intimate understanding of his subjects that transcended mere visual observation. He knew how a horse moved under stress, how a rope coiled and flew, how a rider shifted weight. This kinetic understanding is evident in his action scenes, which possess a sense of immediacy and realism rarely matched. Unlike some contemporaries who might have leaned towards more dramatic or romanticized interpretations, such as the heroic depictions sometimes found in the work of Frederic Remington, Borein focused on the authentic details of everyday ranch work and Native American life.

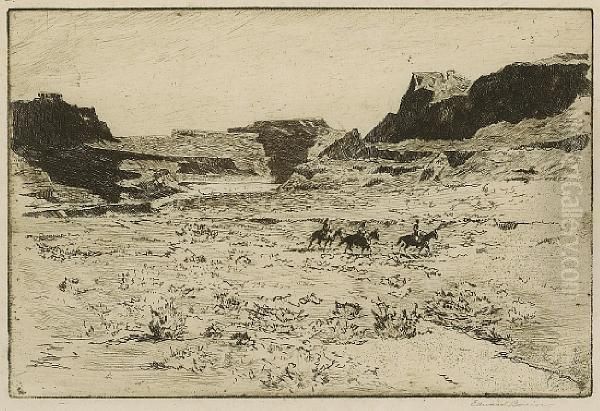

In his etchings, Borein exploited the medium's potential for fine detail and tonal variation. He used intricate networks of lines to build form, suggest texture (the rough hide of cattle, the woven pattern of a Navajo blanket), and create atmospheric effects. His control over the etching process allowed him to achieve rich blacks and delicate grays, effectively capturing the harsh sunlight and deep shadows of the Western landscape. His watercolors, often characterized by luminous washes and precise drawing, similarly emphasized realism and clarity. While aware of modernist trends, Borein remained steadfastly representational, believing his primary duty was to accurately record the West he knew before it disappeared entirely. His contemporaries, like members of the Taos Society of Artists such as Joseph Henry Sharp, E. Irving Couse, or Oscar E. Berninghaus, often explored color and light in a more impressionistic or stylized manner, highlighting Borein's distinct focus on linear precision and documentary truth.

Key Themes: The Vanishing West Preserved

The overarching theme in Edward Borein's work is the documentation of the American West, particularly the elements he perceived as rapidly fading: the traditional cowboy life, the missions of California, and the cultures of Native American peoples. He approached these subjects with a deep respect born of familiarity and a sense of urgency to record them before they were lost to modernization.

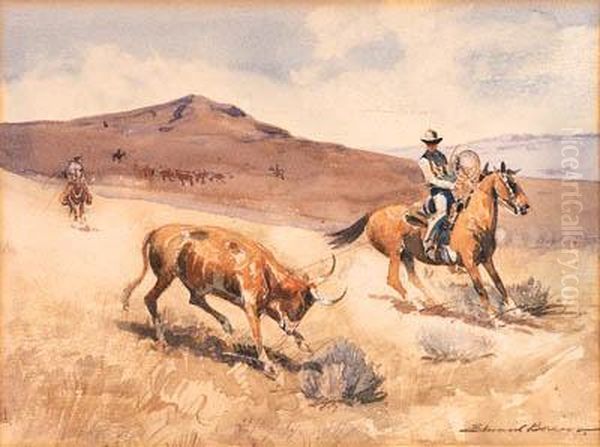

The cowboy, or more accurately, the California vaquero and the working ranch hand, is perhaps his most iconic subject. Borein depicted every aspect of their lives: the action-packed moments of branding, roping, and bronc riding, as well as quieter scenes of riders traversing vast landscapes or resting by a campfire. His vaqueros are skilled professionals, their expertise evident in their posture and handling of horses and cattle. He meticulously rendered their specific gear – the saddles, spurs, hats, and chaps – providing invaluable historical documentation of regional variations in cowboy culture.

Native American life was another crucial theme. Borein traveled extensively in Arizona and New Mexico, spending time among the Navajo, Hopi, and other tribes. He depicted their daily lives, ceremonies, and portraits with sensitivity and accuracy, avoiding the stereotypes prevalent at the time. His portrayals of Native Americans emphasize dignity and cultural integrity. Works like Navajo Land showcase not only the people but their deep connection to the dramatic Southwestern landscape.

The historic Spanish missions of California held a special fascination for Borein. He rendered these architectural landmarks repeatedly, capturing their unique blend of Spanish colonial design and the patina of age. These works, such as his famous etching Mission Santa Barbara No. 3, are more than just architectural studies; they evoke a sense of history and the enduring legacy of California's past. Through these themes, Borein created a comprehensive visual record of the West, preserving its diverse facets for future generations. His dedication to these subjects paralleled the efforts of artists like W. Herbert Dunton, who also sought to capture the authentic West before it changed forever.

Representative Works: Etchings and Watercolors

While Borein worked proficiently in oil, his reputation rests most firmly on his exceptional etchings and watercolors. His etchings, numbering over 400 distinct plates, represent a monumental achievement in American printmaking and form the core of his legacy. These prints cover the full range of his Western subjects, showcasing his mastery of line, composition, and tonal control.

Mission Santa Barbara No. 3 is one of his most recognized etchings. It depicts the iconic facade of the Santa Barbara Mission with remarkable detail and atmospheric depth. The play of light and shadow across the building's surfaces, rendered through intricate cross-hatching, demonstrates his technical virtuosity. Other notable etchings capture the dynamism of cowboy life, such as scenes of roping steers, riding bucking broncos, or driving cattle through rugged terrain. Titles like The Canyon of Death or prints depicting pack trains navigating mountain passes convey the drama and challenges of Western life.

His Native American subjects are equally compelling in etched form. Prints depicting Navajo riders against dramatic mesas or Hopi ceremonial dancers capture cultural moments with ethnographic accuracy and artistic power. Borein’s ability to render textures – the wool of a sheep, the weave of a blanket, the feathers of a headdress – through the etched line is particularly noteworthy.

Borein's watercolors complement his etchings, often exploring similar themes but with the added dimension of color. These works are characterized by their clarity, luminosity, and precise drawing. He used transparent washes effectively to capture the unique light of the West, whether the bright sunshine of midday or the softer tones of dawn and dusk. Watercolors depicting pack trains, mission courtyards, or desert landscapes showcase his skill in rendering atmosphere and space. While perhaps less numerous than his etchings, his watercolors are highly prized for their freshness and directness, often serving as finished works in their own right rather than just studies for prints or oils. His skill in this medium invites comparison with other Western watercolorists, though Borein's style remained distinctly linear and detailed.

Friendships and Connections: A Circle of Western Enthusiasts

Edward Borein moved within a wide circle of friends and acquaintances that included fellow artists, writers, actors, and even a president, all united by a shared fascination with the American West. His long-standing friendship with Maynard Dixon, begun during their brief time at art school in San Francisco, endured throughout their lives. They shared a deep commitment to depicting the West authentically, though their artistic styles diverged over time.

Perhaps his most famous artistic friendship was with Charles M. Russell, the renowned "cowboy artist" of Montana. Borein and Russell shared a mutual respect rooted in their shared experiences of Western life. They met on several occasions, most notably attending the first Calgary Stampede together in 1912. This event, featuring displays of rodeo skills and Native American culture, provided rich subject matter for both artists. While Russell's style was often more narrative and painterly, both men were revered for the authenticity of their depictions, setting a standard for Western art.

In New York, Borein connected with illustrators like Olaf Seltzer (a Russell protégé) and Jimmy Swinnerton. Later, in Santa Barbara, his circle included artists like Carl Oscar Borg, known for his paintings of the Southwest, and landscape painter DeWitt Parshall. He also maintained friendships with artists who passed through or settled in the region, potentially including Nicolai Fechin during Fechin's later California years. Discussions about art, including modernism, occurred with contemporaries like Harold Von Schmidt, another prominent illustrator and painter of Western scenes.

Beyond the art world, Borein cultivated significant friendships. He was close with the humorist and actor Will Rogers, another figure who embodied the Western spirit for many Americans. Their shared love of horses and cowboy culture cemented their bond. Borein also counted President Theodore Roosevelt among his admirers and friends. Roosevelt, a noted historian of the West and a proponent of the "strenuous life," appreciated the accuracy and vitality of Borein's work. These connections underscore Borein's standing not just as an artist, but as a respected authority on Western life and culture, moving comfortably among the leading figures of his time, including perhaps interactions with artists focused on California landscapes like William Wendt or Guy Rose, though Borein's thematic focus remained distinct. His network also likely included interactions with figures like Frank Tenney Johnson, known for his nocturnes of the West.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Legacy

Throughout his career, Edward Borein achieved significant recognition for his work. His early exhibitions in New York (1915, 1917) were critical successes, helping to launch his national reputation. After settling in Santa Barbara, his El Paseo studio functioned as a permanent exhibition space, attracting collectors and admirers. He participated in various group shows and continued to exhibit his work, solidifying his status as a leading Western artist.

Academic and critical appraisal often highlighted the authenticity and technical skill inherent in his work. He was praised for his draftsmanship, his mastery of etching, and his deep understanding of his subjects. Unlike artists who might have visited the West briefly, Borein's decades of lived experience gave his work an undeniable authority. He was seen, alongside Russell and perhaps Remington (though Remington died earlier, in 1909), as one of the key visual chroniclers of the cowboy era. His focus on California and the Southwest, and his particular expertise in etching, carved out a unique niche for him.

Today, Borein's legacy is preserved through major museum collections and continued interest from collectors and historians. The Santa Barbara Historical Museum holds a significant collection of his work, including his reconstructed studio, offering visitors insight into his life and creative process. The Rockwell Museum in Corning, New York, also features his work prominently within its collection of American Western art. Numerous exhibitions have been dedicated to his work posthumously, such as "Edward Borein: The Artist's Life and Work" at the Palm Springs Desert Museum (1999) and "Edward Borein: Etched by the West" at the Santa Barbara Historical Museum (2021). Several books cataloging his etchings and exploring his life have also been published, ensuring his contributions are well-documented.

His influence extends to subsequent generations of Western artists who value accuracy and direct experience. Borein's dedication to documenting the "vanishing West" provides an invaluable historical record, capturing the nuances of a specific time and place with unparalleled fidelity. He remains a benchmark for artists seeking to portray the authentic spirit of the American West, particularly the heritage of the California vaquero and the landscapes of the Pacific Slope and Southwest.

The Enduring Appeal of Borein's West

John Edward Borein passed away in Santa Barbara in 1945, leaving behind a rich legacy captured in countless drawings, watercolors, paintings, and, most significantly, his masterful etchings. His life spanned a period of immense change in the American West, witnessing the transition from the open range to a more settled, modern era. His art serves as a vital bridge to that earlier time, preserving the details, skills, and spirit of the cowboy, the vaquero, and the Native American cultures he knew and respected.

His enduring appeal lies in the palpable authenticity of his work. Viewers sense the dust, feel the movement of the horses, and appreciate the quiet dignity of his subjects. Borein was not merely illustrating a romantic notion of the West; he was documenting a reality he had intimately experienced. His technical proficiency, particularly his command of line and mastery of etching, provided the perfect vehicle for his observations, allowing him to render complex scenes with clarity and precision.

Compared to the sometimes more dramatic or idealized visions of the West presented by others, Borein offers a grounded, knowledgeable perspective. He stands as a testament to the value of direct experience in art, proving that deep understanding of a subject can lead to profound and lasting artistic expression. For anyone seeking to understand the visual history of the American West, particularly the world of the working cowboy and the heritage of California and the Southwest, the art of Edward Borein remains an essential and rewarding destination. His work continues to resonate, offering a window into a world he knew intimately and captured with unparalleled skill and honesty.