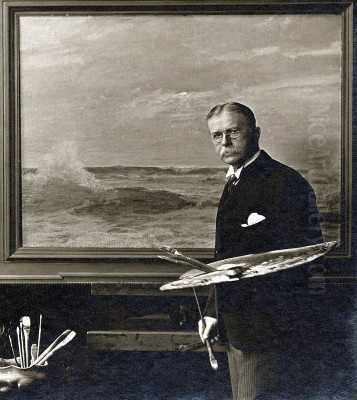

Howard Russell Butler (1856-1934) stands as a unique figure in American art history, a man whose life and work elegantly bridged the seemingly disparate worlds of art, science, and architecture. He was not merely a painter but an innovator, an astronomer’s collaborator, and a visionary thinker whose canvases captured both the fleeting beauty of the terrestrial landscape and the awe-inspiring grandeur of celestial events. His legacy is built upon a foundation of rigorous scientific understanding combined with a profound artistic sensibility.

Born into a prosperous New York City family in 1856, Butler's early path did not immediately point towards an artistic career. He pursued scientific studies at Princeton University, focusing on physics, which provided him with a deep appreciation for the natural laws governing the universe. Following his time at Princeton, he obtained a law degree from Columbia University, suggesting a future in a more conventional profession.

A Pivot Towards Art

Despite his training in science and law, the pull towards artistic expression proved irresistible. At the age of 28, Butler made the decisive choice to dedicate his life to becoming a professional artist. This was not a whimsical decision but a committed turn towards a field where he could integrate his diverse interests. He sought formal training to hone his craft, studying at the renowned Art Students League of New York, an institution known for fostering progressive artistic ideas, including the burgeoning movement of American Impressionism.

His quest for artistic knowledge extended beyond American shores. Butler traveled to Paris, the epicenter of the art world at the time. There, he absorbed the lessons of Impressionism, studying the works and perhaps interacting with artists who prioritized light, color, and capturing transient moments. Influences from this period might include figures like the French naturalist painter Jules Bastien-Lepage, known for his blend of academic precision and plein-air observation.

Further broadening his horizons, Butler journeyed to Mexico. Significantly, he studied there with Frederic Edwin Church, a preeminent figure of the later Hudson River School. Church was celebrated for his meticulously detailed and often dramatic landscapes of North and South America. This mentorship undoubtedly deepened Butler's skills in landscape depiction and perhaps reinforced his inclination towards capturing nature's grandeur, albeit through a potentially more modern lens than Church's own.

Influences and Artistic Circles

Butler's developing style reflected this rich tapestry of experiences. His scientific background instilled a respect for accuracy and observation, while his exposure to Impressionism encouraged a bolder use of color and a focus on atmospheric effects. The influence of the Hudson River School, particularly through Church, can be seen in the scale and scope of some of his landscape work. He navigated these influences to create a distinct artistic voice.

He was active within the vibrant New York art scene. His association with the Art Students League placed him amidst contemporaries who were shaping American art. Figures like Childe Hassam, William Merritt Chase, and potentially interactions with visiting artists like John Singer Sargent (whose portraiture and fluid brushwork were highly influential) formed the backdrop of his artistic development. Butler wasn't working in isolation; he was part of a generation exploring new ways of seeing and painting the American experience. His work at the Vanderbilt Gallery further immersed him in these circles.

The Eclipse Painter: Art Meets Astronomy

Perhaps Howard Russell Butler's most enduring fame comes from his extraordinary paintings of solar eclipses. In an era before reliable color photography, capturing the ephemeral beauty and scientific detail of a total solar eclipse posed a significant challenge. Butler, uniquely equipped with his artistic skill and scientific mind, rose to this challenge, becoming a pioneer in the field of astronomical art.

He developed a specific technique to record the fleeting moments of totality, which often lasts only minutes. This involved intense observation, rapid sketching in monochrome to capture forms and structure, and detailed color notes dictated aloud to an assistant. Immediately following the event, he would translate these sketches and notes into finished oil paintings. He possessed what was described as a rare ability to retain a vivid mental image, allowing him to render the intricate details of the solar corona and prominences with remarkable accuracy.

His talent did not go unnoticed by the scientific community. The United States Naval Observatory invited Butler to join their expedition to Baker, Oregon, to observe and record the total solar eclipse of June 8, 1918. This collaboration marked a significant moment of synergy between art and science. The resulting painting was highly acclaimed for both its aesthetic power and its scientific fidelity.

Butler continued to chase eclipses, documenting the one in Lompoc, California (1923) and another in Middletown, Connecticut (1925). He created monumental triptychs depicting these three eclipses. Initially intended for a proposed (but never built) astronomical center at Princeton, these magnificent works eventually found a permanent home at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City, where they continue to inspire awe and educate visitors in the Hayden Planetarium sphere. He also painted the 1932 eclipse. These works remain invaluable records, capturing details and colors in a way that early black-and-white photography could not.

Astronomical Visions Beyond Eclipses

Butler's fascination with the cosmos extended beyond solar eclipses. He applied his unique blend of skills to other celestial subjects. He produced a series of five paintings depicting dramatic hydrogen prominences – massive eruptions of plasma from the Sun's surface (chromosphere). These works translate complex astrophysical phenomena into visually stunning compositions, again demonstrating his ability to make science accessible and beautiful through art.

His astronomical interests also led him to depict other worlds. One notable work is Mars As Seen from Its Outer Moon "Deimos". This painting, based on the scientific understanding of the time, offers a speculative yet informed visualization of the Martian landscape viewed from its small, outer satellite. It showcases his willingness to use art to explore and communicate scientific concepts about our solar system, predating much of the space art genre later popularized by artists like Chesley Bonestell.

Further cementing his commitment to the intersection of art and science, Butler authored a book titled Painter and Space: or The Third Dimension in Painting, published in 1923. In this work, he explored the scientific principles behind representing depth and volume on a two-dimensional canvas, sharing his insights into perspective, light, and form, likely drawing heavily on his physics background.

Capturing the American Landscape

While renowned for his astronomical art, Butler was also a highly accomplished landscape and marine painter. His travels provided ample inspiration. He painted numerous seascapes, particularly during his time spent in California. Works like Yankee Point, Monterey (created between 1921-1926) exemplify his skill in capturing the dynamic interplay of light, water, and coastline, often employing the broken brushwork and vibrant palette associated with Impressionism. This painting is sometimes referred to as his "last California marine painting."

His artistic gaze also turned towards the dramatic scenery of the American West. He undertook expeditions to paint the majestic landscapes of the Colorado Plateau and Zion National Park in Utah. For Zion, he created a series of seven canvases capturing the monumental scale and unique geological formations of the region. These works resonate with the tradition of grand landscape painting established by Hudson River School artists like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, and particularly echo the Western vistas of Albert Bierstadt, yet filtered through Butler's own stylistic sensibilities. His ability to render light and atmosphere remained paramount, whether depicting a rocky canyon or a coastal scene, drawing comparisons in marine subjects to the powerful work of Winslow Homer.

Architectural Pursuits and Patronage

Butler's talents were not confined to the canvas. He possessed a keen interest in architecture and design, particularly in service of art and science. He played a significant role in the founding of the American Fine Arts Society in New York City and was involved in the creation of its headquarters, the American Fine Arts Building.

His most notable architectural association involved the industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. Butler was instrumental in persuading Carnegie to fund the creation of Lake Carnegie in Princeton, a project intended to provide the university with a venue for rowing and recreation. While successful in securing the funding, the project proved more complex and costly than anticipated, reportedly straining the relationship between the two men. Carnegie was famously quoted as calling the lake project "the worst scrape I ever got into."

Despite this, Butler's connection with Carnegie also extended to other projects. He is credited with involvement, possibly in an advisory or design capacity, with the planning or early concepts related to Carnegie Hall in New York City, one of the world's most prestigious concert venues, often associated with architect William Burnet Tuthill. Butler also designed an idealized museum building concept intended for Carnegie Libraries and contributed designs for the astronomical hall at the American Museum of Natural History, further linking his artistic vision with public institutions of science and culture. His architectural activities, much like his painting, often sought to create spaces where art and knowledge could intersect, placing him in the context of contemporary architects like Stanford White who were shaping the civic landscape.

Community Leadership and Recognition

Beyond his specific artistic and architectural projects, Howard Russell Butler was an active figure in his communities. He was recognized as a leader, contributing to civic life in places like Princeton. His role as a founder of the American Fine Arts Society underscores his commitment to fostering the arts in America. He was not merely a solitary artist but someone engaged with the institutional and social structures supporting artistic endeavors.

His work received recognition both during his lifetime and posthumously. His paintings were exhibited widely, including at the prestigious Paris Salon, indicating international acknowledgment. He garnered awards and was elected to prominent art organizations, solidifying his reputation among peers and critics.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis

Howard Russell Butler's artistic style is best understood as a synthesis of his diverse experiences and interests. It incorporated the Impressionists' attention to light, color, and atmosphere, particularly evident in his landscapes and seascapes. Yet, this was always tempered by a strong sense of realism and structural integrity, likely rooted in his scientific training and his studies with figures like Church.

His astronomical works are unique in their meticulous accuracy, striving to represent celestial phenomena as faithfully as possible within the medium of paint. He employed bold compositions and often worked on a large scale, suitable for capturing the grandeur of both natural landscapes and cosmic events. His brushwork could range from controlled and detailed in scientific depictions to more fluid and expressive in his landscapes. Ultimately, his style was uniquely his own, defined by its remarkable fusion of observational precision and artistic interpretation.

Legacy and Historical Position

Howard Russell Butler occupies a significant and unique place in American art history. His primary contribution lies in his pioneering work at the intersection of art and science. His eclipse paintings, created before the advent of effective color photography, are not merely beautiful artworks but also valuable historical and scientific documents. They captured transient phenomena with a fidelity that technology of the day could not match, earning the respect of astronomers like Jay Pasachoff decades later.

His work demonstrated that art could be a powerful tool for scientific communication and visualization, making complex astronomical concepts accessible and engaging to a wider public. His paintings were used in educational contexts and helped popularize astronomy. While later technologies like spectroscopy provided different kinds of data, Butler's paintings remain unparalleled in their holistic, visual representation of the awe-inspiring spectacle of a total solar eclipse.

His contributions to landscape painting, particularly his depictions of the California coast and the American West, secure his place within the broader narrative of American art. His involvement in architectural projects and arts organizations further highlights his multifaceted engagement with the cultural life of his time. Today, his works are held in major collections, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the National Gallery of Art, and prominently at the American Museum of Natural History, ensuring his legacy endures.

Conclusion

Howard Russell Butler was more than a painter; he was a polymath whose curiosity spanned the arts and sciences. He saw no inherent conflict between rigorous observation and aesthetic expression. Whether capturing the fleeting light on the Pacific Ocean, the monumental geology of Zion, or the ethereal glow of a solar corona, his work was unified by a deep reverence for the natural world and the cosmos. He remains a compelling example of how artistic vision and scientific understanding can combine to produce works of enduring beauty and significance, leaving a legacy as luminous and multifaceted as the subjects he chose to paint. He died in Princeton in 1934, leaving behind a body of work that continues to fascinate and inspire.