Introduction: An Artist of the British Landscape

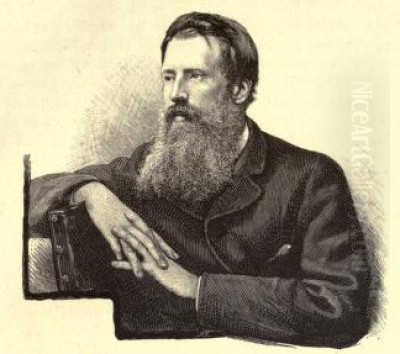

Henry William Banks Davis stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th-century British art. Born in Finchley, Middlesex, then a rural area north of London, on August 26, 1833, and passing away on December 1, 1914, Davis dedicated his long life to capturing the nuances of the natural world. Primarily known as a painter, his artistic journey began with sculpture, but he soon found his true calling in depicting the pastoral scenes and animal life of Great Britain and Northern France. His commitment to realism, combined with a sensitive eye for light and atmosphere, earned him considerable recognition during his lifetime, most notably his election as a full member of the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts. He remains celebrated for his tranquil yet detailed portrayals of the countryside, particularly featuring sheep and cattle within their native environments.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Henry William Banks Davis, often signing his work as H.W.B. Davis, entered a world where artistic pursuits were valued within his family. His father was a barrister, providing a stable background, while his mother was an amateur artist, likely fostering his early interest in visual expression. This supportive environment paved the way for his formal artistic education. In December 1851 (some sources state 1852), at the age of 18 or 19, he enrolled in the highly competitive Royal Academy Schools in London. Initially, his focus was on sculpture, a demanding discipline requiring a strong understanding of form and anatomy. His talent in this area was quickly recognized; he won medals for his modelling skills, demonstrating a proficiency that would later inform the solidity and anatomical accuracy of his painted animals.

Despite this early success in three dimensions, the allure of colour and the expansive possibilities of landscape proved stronger. Davis began to transition towards painting, a medium that allowed him to explore the effects of light, weather, and the subtle textures of the natural world more fully. This shift marked the beginning of a long and productive career dedicated to capturing the essence of rural life on canvas. His foundational training in sculpture, however, arguably provided him with a distinct advantage in rendering the weight, structure, and movement of the animals that would become central to his oeuvre.

The Turn to Painting and French Influence

The mid-1850s marked a definitive turn in Davis's career path. While he had shown promise as a sculptor, painting became his primary focus. His first significant public recognition as a painter came in 1855 when two of his landscape works were accepted for exhibition at the Royal Academy's annual show. This was a crucial step for any aspiring artist in Britain, signifying entry into the professional art world. The acceptance of these early works likely solidified his decision to pursue painting more seriously.

Seeking new subjects and perhaps a different artistic environment, Davis spent a considerable period residing near Boulogne-sur-Mer in Northern France. This region, with its rolling dunes, coastal light, and pastoral farmland, offered a wealth of inspiration. His time in Picardy was highly productive, resulting in numerous canvases depicting the local scenery, often featuring the characteristic sheep and cattle of the area. This French sojourn exposed him to different landscapes and possibly different artistic currents, although his style remained rooted in a distinctly British form of detailed realism rather than embracing the nascent Impressionist movement developing elsewhere in France. The paintings from this period often possess a specific sense of place, capturing the unique light and atmosphere of the Pas-de-Calais region.

Mature Style: Capturing Nature's Realism

H.W.B. Davis developed a mature style characterized by meticulous realism and a deep sensitivity to the natural environment. His landscapes were not merely topographical records but carefully composed scenes imbued with atmosphere and a sense of tranquility or, occasionally, drama. He excelled at rendering the effects of light, whether the warm glow of late afternoon sun, the cool clarity of midday, or the soft diffusion of light on an overcast day. His skies are often active participants in the composition, contributing significantly to the overall mood of the piece.

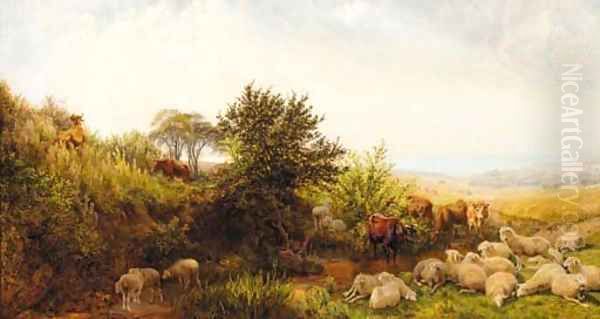

His true mastery, however, lay in the combination of landscape and animal painting. Unlike some contemporaries who might treat animals as mere accessories, Davis gave them central importance. He possessed an exceptional understanding of animal anatomy and behaviour, particularly sheep and cattle, which he depicted with convincing naturalism. His animals are not idealized or overly sentimentalized; they are shown grazing, resting, or moving through the landscape in a believable manner. He often focused on breeds specific to the regions he painted, whether the hardy sheep of the Welsh hills, the sturdy cattle of the Scottish Highlands, or the pastoral flocks of Picardy. This integration of accurately rendered animals within specific, carefully observed landscapes became the hallmark of his work.

A Career at the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts was the epicentre of the British art world in the 19th century, and achieving recognition within its ranks was paramount for an artist's career. H.W.B. Davis steadily climbed its ladder of prestige. Having first exhibited there in 1853 (or 1855, sources vary slightly on the very first exhibit), he became a consistent contributor to the annual Summer Exhibition, the most important art event of the London season. His regular presence demonstrated his growing reputation and the consistent quality of his output.

His dedication and talent were formally acknowledged on January 28, 1873, when he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA). This was a significant honour, placing him among the country's leading artists. Just four years later, on June 18, 1877, he achieved the highest distinction by being elected a full Royal Academician (RA). This lifetime appointment cemented his status within the British art establishment. As an RA, Davis not only gained prestige but also participated in the governance of the Academy and had preferential placement for his works in the exhibitions. His long association with the RA underscores his position as a respected and successful artist within the mainstream tradition of Victorian painting.

Masterworks: Depicting the Pastoral and the Wild

Throughout his long career, H.W.B. Davis produced a substantial body of work, with several paintings achieving particular renown and exemplifying his characteristic style. These works often capture specific moments in the daily life of rural Britain and France, showcasing his skill in both landscape and animal depiction.

Returning to the Fold (Exhibited RA 1880): This title, used for more than one work, typically depicts a shepherd guiding his flock home as evening approaches. Such scenes allowed Davis to explore the effects of twilight, casting long shadows and suffusing the landscape with a warm, often golden light. The painting showcases his intimate knowledge of sheep behaviour and his ability to create a peaceful, pastoral mood, evoking a sense of harmony between humanity, animals, and nature. It speaks to the enduring rhythms of agricultural life.

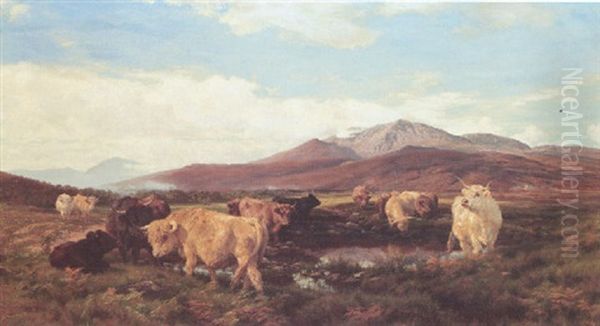

Rough Pasturage (Exhibited RA 1867): Often set in the rugged landscapes of Wales or Scotland, works with this theme depict hardy breeds of sheep or cattle grazing on challenging terrain. Davis excelled at capturing the textures of rocky outcrops, coarse grasses, and windswept hillsides. These paintings highlight the resilience of animals adapted to harsh environments and demonstrate his ability to convey the wilder aspects of the British landscape, contrasting with his more serene pastoral scenes.

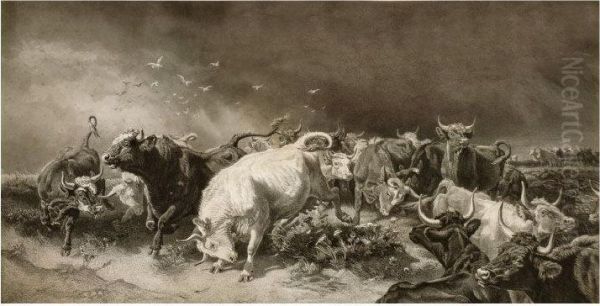

The Panic (Exhibited RA 1890) / A Panic (Exhibited RA 1874): These dramatic works depict herds of cattle or flocks of sheep suddenly startled and stampeding. They represent a departure from his usually tranquil subjects, allowing Davis to explore dynamic movement and animal psychology under stress. Capturing the chaos and energy of a stampede required considerable skill in rendering anatomy in motion and composing a complex, multi-figure scene. These paintings demonstrate his versatility and ability to handle more dramatic themes within his chosen genre.

Now Came Still Evening On (Exhibited RA 1884): The title, borrowed from John Milton's Paradise Lost, immediately sets a poetic and contemplative mood. These paintings typically feature serene landscapes bathed in the soft light of dusk. Cattle might be seen resting by a tranquil river, or sheep grazing peacefully as the day ends. Davis masterfully uses subtle colour gradations and soft focus to evoke the quiet transition from day to night, creating a deeply atmospheric and often moving image of rural peace.

After Sunset (Exhibited RA 1887): Similar in mood to his evening scenes, works titled After Sunset focus on the lingering light and colour in the sky after the sun has dipped below the horizon. Davis was adept at capturing the fleeting violets, pinks, and oranges of twilight, reflecting them in water or casting a soft glow over the land. These paintings often possess a quiet, melancholic beauty, emphasizing the transient nature of light and time.

Mother and Son (Exhibited RA 1881): This title suggests a more intimate focus on animal relationships, likely depicting a cow with her calf or a ewe with her lamb. Such works allowed Davis to explore themes of maternal care and the bonds between animals, often imbued with a gentle sentiment popular with Victorian audiences, yet rendered with his characteristic anatomical accuracy and lack of excessive anthropomorphism.

Flow'ry May (Exhibited RA 1896): Celebrating the arrival of spring, paintings like this would depict landscapes bursting with new life – lush green pastures dotted with wildflowers, and young animals enjoying the warmer weather. Davis captured the freshness and vibrancy of the season, using brighter palettes and emphasizing the abundance of nature.

Ben Eay / Scottish Highlands: Davis frequently travelled to Scotland, drawn by its dramatic mountains, lochs, and hardy Highland cattle. Paintings depicting specific locations like Ben Eay showcase his ability to render majestic mountain scenery, often contrasting the scale of the landscape with the animals grazing below. He captured the unique atmosphere and rugged beauty of the Highlands with fidelity.

Picardy Dunes / French Scenes: Harking back to his time near Boulogne, Davis continued to paint scenes inspired by Northern France throughout his career. These might include coastal views with windswept dunes, quiet farmsteads, or flocks of sheep grazing on the chalky downlands characteristic of the region. They often possess a distinct quality of light compared to his British scenes.

Midday: While less evocative than his sunset or evening scenes, paintings depicting midday allowed Davis to explore the effects of strong, direct sunlight. He would capture the clarity of the light, the sharp contrasts between sunlit areas and shadows, and the sense of warmth and stillness that can pervade the countryside during the middle of the day.

Though primarily remembered as a painter, it's worth recalling that Davis's artistic journey began with sculpture. While few examples of his sculptural work are widely known today compared to his vast output of paintings, his early training undoubtedly contributed to the three-dimensional quality and anatomical correctness that characterize his painted animals. His primary legacy, however, firmly rests upon his canvases.

Contemporaries and the Victorian Art Scene

H.W.B. Davis worked during a vibrant and complex period in British art history, the Victorian era. He was a contemporary of numerous other artists, particularly those specializing in landscape and animal painting, and operated within the influential sphere of the Royal Academy. Understanding his place requires considering the artistic landscape he inhabited.

In the realm of animal painting, the towering figure was Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873). Landseer's dramatic, often anthropomorphic depictions of animals, particularly stags and dogs, were immensely popular. Davis's work, while sharing a focus on animals, generally offered a more naturalistic and less narrative approach, focusing on the integration of animals within their environment rather than overt storytelling or sentimentality, although some pathos is present in works like Mother and Son.

Closer to Davis's specific subject matter was Thomas Sidney Cooper (1803-1902), another long-lived Royal Academician famous for his paintings of cattle and sheep, often set in the meadows of Kent. Cooper and Davis shared a dedication to pastoral subjects and meticulous rendering, though their handling of paint and atmosphere differed. Both catered to a strong public demand for peaceful rural scenes. Briton Rivière (1840-1920) was another prominent RA known for animal subjects, often with historical or literary themes, representing a different facet of animal painting compared to Davis's focus on contemporary rural life. The tradition of equine art was upheld by figures like John Frederick Herring Sr. (1795-1865) and his son, John Frederick Herring Jr. (1820-1907), whose detailed horse portraits and racing scenes occupied a distinct niche.

Within landscape painting, Davis's contemporaries included the highly popular Benjamin Williams Leader (1831-1923), whose picturesque views of the English and Welsh countryside, often featuring silver birches and glowing sunsets, resonated strongly with public taste. While sharing some landscape motifs, Leader's style was generally broader and more overtly picturesque than Davis's detailed realism. George Vicat Cole (1833-1893), born the same year as Davis, was another successful landscape painter known for his lush depictions of southern England, particularly Surrey and the Thames Valley.

The influence of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, though waning by the time Davis reached full maturity as an artist, had left its mark on British landscape painting through figures like John Brett (1831-1902), known for his incredibly detailed coastal scenes and landscapes, executed with a scientific precision that differed from Davis's more atmospheric approach. Watercolour specialists like Myles Birket Foster (1825-1899) captured idealized rural life, while oil painters like Alfred William Hunt (1830-1896) produced atmospheric landscapes influenced by Turner. The unique, often nocturnal urban and dockland scenes of Atkinson Grimshaw (1836-1893) offered a stark contrast to Davis's sunlit or moonlit pastoralism.

Davis's time in France also places him chronologically alongside the Barbizon School painters like Constant Troyon (1810-1865) and the celebrated female animal painter Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899), who emphasized realism and direct observation of nature. While direct influence is difficult to trace, the broader European movement towards realism certainly formed part of the artistic climate Davis experienced.

His career at the Royal Academy spanned the presidencies of figures like Sir Francis Grant (President 1866-1878), Frederic Leighton (President 1878-1896), and Sir John Everett Millais (President 1896). Davis navigated this institutional landscape successfully, maintaining his distinct artistic voice while adhering to the standards of representation and finish valued by the Academy and its patrons during much of his active period. He was part of a generation that upheld traditional skills in drawing and composition within the established genres of landscape and animal art.

Legacy and Collections

Henry William Banks Davis enjoyed considerable success and respect during his lifetime. His regular inclusion in the Royal Academy exhibitions, culminating in his election as a full Academician, attests to his standing within the official art world. His paintings found favour with Victorian collectors who appreciated his skillful rendering, familiar subject matter, and often tranquil depictions of the British and French countryside. He was seen as a reliable and accomplished artist, a master of his chosen niche.

In the decades following his death in 1914, as artistic tastes shifted dramatically towards Modernism, the reputation of many Victorian academic painters, including Davis, experienced a decline. The detailed realism and pastoral themes that were once highly valued fell out of critical favour. However, in more recent times, there has been a renewed appreciation for the technical skill and historical context of Victorian art. Davis is now recognized as one of the foremost British animal and landscape painters of the latter half of the 19th century. His work provides valuable insight into the rural life and artistic tastes of the period.

His legacy is preserved not only in the historical record but also through the presence of his works in numerous public collections. Major institutions in the United Kingdom hold examples of his paintings, ensuring their accessibility to future generations. These include:

Tate Britain, London: Holds several works, including significant landscapes and animal studies.

Royal Academy of Arts Collection, London: As an RA, his Diploma Work (After Sunset) is held here, along with other potential holdings.

Victoria and Albert Museum, London: May hold works, particularly drawings or watercolours.

Manchester Art Gallery: Often features strong collections of 19th-century British art.

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool: Part of National Museums Liverpool, known for its Victorian collection.

Birmingham Museums Trust: Holds a significant collection of British art.

Various other regional galleries throughout the UK, particularly those with strong 19th-century holdings, are likely to possess works by H.W.B. Davis.

While perhaps not as widely known today as Landseer or some of the Pre-Raphaelites, H.W.B. Davis remains an important figure for understanding the mainstream of British art in the Victorian era. His dedication to realism, his profound understanding of animal life, and his ability to capture the specific atmospheres of the landscapes he loved secure his place in the history of British art.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Rural Life

Henry William Banks Davis RA carved a distinct and respected niche for himself within the bustling art world of Victorian Britain. From his early training in sculpture to his long and successful career as a painter of landscapes and animals, he remained dedicated to a vision of realistic representation combined with sensitivity to the natural world. His canvases, whether depicting the sun-drenched fields of Picardy, the rugged hills of Wales, the misty Highlands of Scotland, or the gentle pastures of England, consistently demonstrate his keen observational skills and technical proficiency.

His particular mastery lay in the seamless integration of animals, especially sheep and cattle, into these landscapes. Rendered with anatomical accuracy and a deep understanding of their behaviour, his animals are convincing inhabitants of their environments, contributing significantly to the mood and authenticity of his scenes. As a long-standing member and eventual full Academician of the Royal Academy, Davis represented the enduring strength of traditional genres and skills within the British art establishment. Though tastes have evolved, his work continues to be appreciated for its craftsmanship, its evocative portrayal of rural life, and its contribution to the rich tapestry of 19th-century British painting. His paintings remain a testament to a lifelong engagement with the beauty and quiet drama of the natural world.