Thomas Sidney Cooper stands as one of the foremost English landscape and animal painters of the Victorian era. His long and prolific career, spanning almost the entire 19th century and extending into the early 20th, earned him considerable fame and the affectionate moniker "Cow Cooper" due to his exceptional skill in depicting cattle. His works captured the idyllic, pastoral heart of the English countryside, particularly his native Kent, offering tranquil scenes that resonated deeply with the public during a period of rapid industrialization.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Canterbury

Thomas Sidney Cooper was born on September 26, 1803, in St Peter’s Street, Canterbury, Kent. His family circumstances were modest, and while he displayed a natural inclination towards art from a young age, formal training was initially beyond his reach. Financial constraints shaped his early path, forcing him to seek practical employment rather than immediate artistic education. This early exposure to the working world, however, inadvertently provided foundational experiences.

At the age of twelve, Cooper began working for a local coach painter. This trade, while seemingly far removed from fine art, offered practical experience in handling paints and brushes, understanding colour mixing, and developing a steady hand. It was a rudimentary, craft-based introduction to the materials of art. He later transitioned to work as a scene painter for about eight years, a role that would have significantly developed his understanding of perspective, composition, and creating large-scale visual effects – skills that would subtly inform his later landscape work.

Despite these practical beginnings, Cooper harboured ambitions for a career in fine art. He diligently sketched and painted in his spare time, honing his observational skills by drawing the architecture and surrounding countryside of Canterbury. His determination eventually led him, around the age of twenty, to seek formal instruction in London.

Formative Years: London and Brussels

Around 1823, Cooper made his way to London, the heart of the British art world. With some assistance, possibly from a relative, he managed to gain admission to the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. This was a significant step, placing him within the orbit of established artists and rigorous academic training, which typically involved drawing from casts and life models. However, his time at the RA Schools was cut short due to a lack of financial support, forcing him to abandon his studies prematurely.

Returning to his hometown of Canterbury, Cooper did not give up. He supported himself by giving drawing lessons and selling sketches and small paintings, often depicting local views and animals. This period was crucial for developing his self-reliance and refining his technique through constant practice and direct observation of the Kentish landscape and its inhabitants, particularly the farm animals that would become his trademark.

A pivotal chapter in Cooper's development began in 1827 when he moved to Brussels. This move broadened his horizons significantly. In Brussels, he found a supportive environment and married Charlotte Pearson in 1829. Critically, he befriended and was profoundly influenced by the renowned Belgian Romantic animal painter, Eugène Verboeckhoven. Verboeckhoven's meticulous technique and his focus on the realistic depiction of livestock, particularly sheep and cattle, resonated with Cooper and undoubtedly shaped his own artistic direction. The influence of 17th-century Dutch masters like Aelbert Cuyp and Paulus Potter, known for their cattle paintings, was also strong in the Low Countries and likely filtered through Verboeckhoven to Cooper.

During his time on the continent, Cooper also travelled, absorbing influences from France, the Netherlands, and potentially parts of Germany (Westphalia) and Switzerland. He continued to teach art while living in Brussels. However, the Belgian Revolution of 1830 forced him and his family to return to England, settling back in London by 1831. This return marked the beginning of his sustained professional career in his home country, armed with new skills and a clearer artistic vision.

Establishing a Reputation in England

Upon his return to London, Cooper was ready to make his mark on the British art scene. His continental experience, particularly the influence of Verboeckhoven and the Dutch tradition, had refined his style. He began exhibiting his work, and a crucial milestone occurred in 1833 when he showed his first painting at the Royal Academy of Arts. This marked the start of an incredibly long and consistent exhibiting career at the RA, with Cooper sending works there almost every year until his death nearly seventy years later.

His chosen subject matter – peaceful scenes of cattle and sheep grazing in sunlit meadows, often set within the recognizable landscapes of Kent – quickly found favour with the Victorian public. These pastoral images offered an appealing contrast to the increasingly urbanized and industrialized reality of 19th-century Britain. Cooper's ability to capture the placid nature of his animal subjects, combined with his detailed rendering of foliage and atmospheric effects, made his work highly desirable.

His reputation grew steadily throughout the 1830s and early 1840s. He became known for his technical proficiency, particularly his skill in painting the textures of animal hides and fleece, and the way light played upon them. This dedication to realism, combined with a gentle, almost sentimental portrayal of rural life, cemented his popularity among collectors and fellow artists.

The Art of Thomas Sidney Cooper: Style and Subject Matter

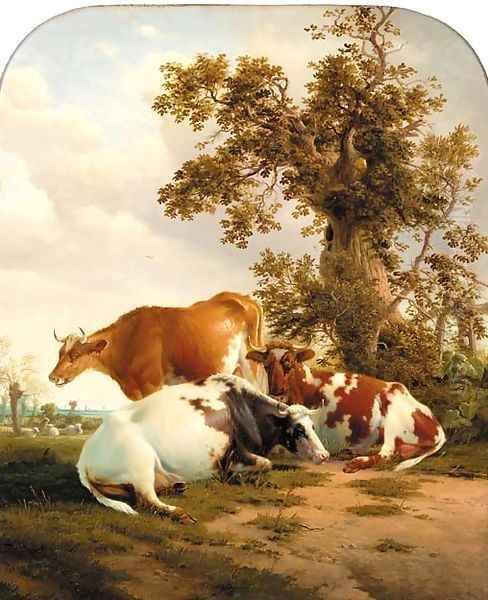

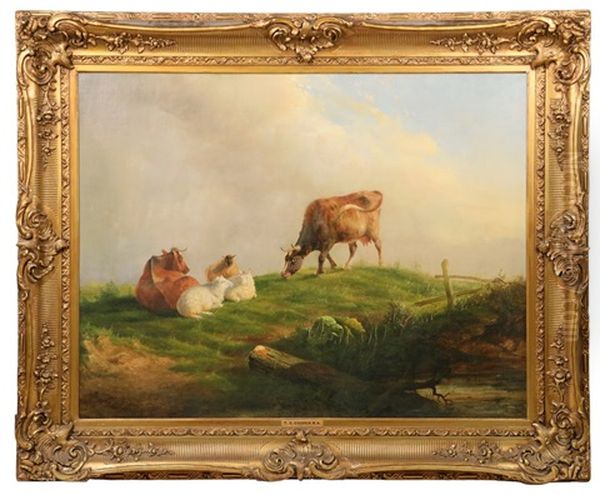

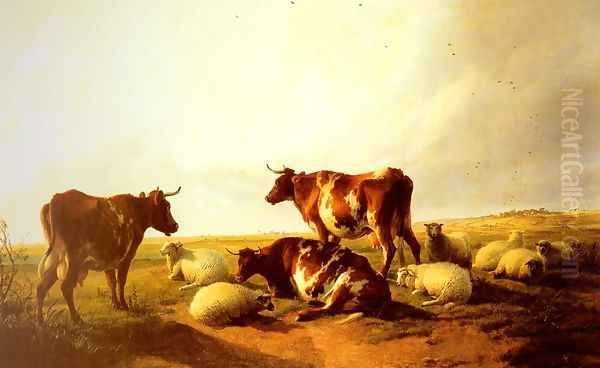

Thomas Sidney Cooper's artistic style is firmly rooted in realism, with a strong allegiance to the traditions of 17th-century Dutch and Flemish animal and landscape painting. His primary subjects were domestic farm animals – cattle, sheep, and occasionally goats or donkeys – depicted within meticulously rendered landscape settings, usually inspired by the meadows and riverbanks of his native Kent.

Cooper possessed an exceptional ability to capture the anatomical accuracy of his animals. He spent countless hours sketching outdoors, observing the forms, postures, and behaviours of livestock. This dedication is evident in the convincing weight and structure of his painted animals. Beyond mere accuracy, he excelled at rendering textures – the rough hide of a cow, the thick fleece of a sheep, the smooth coat of a horse. His handling of light, often depicting animals bathed in the warm glow of morning or late afternoon sun, added depth and a sense of tranquil atmosphere to his scenes.

His landscapes, while often serving as backdrops for the animals, were painted with considerable care. He depicted the lush greens of English pastures, the gentle flow of rivers like the Stour, and the specific character of trees and distant hills with faithfulness. Unlike the dramatic, sublime landscapes of contemporaries like J.M.W. Turner, or the focus on fleeting light effects seen in John Constable's work, Cooper's vision was one of enduring pastoral calm and stability. His compositions are typically balanced and harmonious, reinforcing the peaceful mood.

While sometimes criticized later for a degree of repetition in his themes, Cooper's consistency was part of his appeal during his lifetime. Patrons knew what to expect: a beautifully executed, reassuring image of rural England. His work stands in contrast to that of Sir Edwin Landseer, another hugely popular Victorian animal painter, whose subjects often carried more narrative weight, anthropomorphism, or dramatic tension (as seen in The Monarch of the Glen). Cooper's focus remained steadfastly on the quiet, everyday life of farm animals in their natural environment.

Signature Works and Recognition

Throughout his long career, Thomas Sidney Cooper produced a vast number of paintings. While many share similar themes, several stand out as representative of his style and skill. Works frequently titled along the lines of Cattle Resting in a Meadow, Sheep Grazing by a River, or simply On a Farm in Kent encapsulate his typical output.

Specific named works often cited include Milking Time (various versions exist), which depicts the daily rhythm of farm life with his characteristic attention to detail in both the animals and the setting. On the Stour (often subtitled Sketch on a Farm in East Kent) showcases his ability to integrate animals seamlessly into the specific Kentish landscape he knew so well. The Shepherdess Tending Her Flock and The Drover introduce human figures, though usually subordinate to the animals and landscape, reinforcing the pastoral theme.

His large canvases, often featuring groups of cattle or sheep dominating the foreground against a detailed landscape background, were particularly popular at Royal Academy exhibitions. A work like Cows in Pasture exemplifies his mastery in rendering the textures of the animals' coats and the play of sunlight on the scene, creating a palpable sense of warmth and tranquility. These works solidified his reputation and led to significant official recognition.

Collaboration and Artistic Circle

While primarily known for his independent work, Thomas Sidney Cooper engaged in collaborations with other artists, most notably the landscape painter Frederick Richard Lee R.A. Beginning around 1847, the two artists produced a number of joint works where Lee, an established landscape specialist, would paint the scenery, and Cooper would add the cattle or sheep. This partnership combined their respective strengths and resulted in popular, well-regarded paintings that often commanded high prices. Their collaborative works highlight the specialization prevalent in the Victorian art market.

Cooper was also acquainted with other prominent artists of his time. While direct collaborative evidence is scarce for others, he certainly moved within the circles of the Royal Academy. He would have known figures like William Powell Frith, famous for his detailed narrative scenes of Victorian life like Derby Day, although the extent of their professional interaction or collaboration mentioned in the source material requires careful verification. The source also mentions William Burgess as a friend Cooper guided, but this might be a confusion, as specific interactions with a notable painter named William Burgess are not widely documented in Cooper's biography; perhaps landscape painter William Burgess of Dover was intended, or another figure entirely.

His artistic context includes the towering figures of British landscape painting who preceded or overlapped with him, such as John Constable and J.M.W. Turner, though Cooper's style differed significantly. More direct contemporaries in the field of animal and rural painting included Sir Edwin Landseer, Richard Ansdell (known for animal and Spanish subjects), and Abraham Cooper (no relation, known for battle scenes and animals). Later landscape painters like Benjamin Williams Leader and watercolourists capturing rural charm like Myles Birket Foster were also part of the broader Victorian art scene Cooper inhabited for so long. His primary influence remained, however, the Belgian Eugène Verboeckhoven and the Dutch Golden Age masters.

The Royal Academy and Esteem

The Royal Academy of Arts played a central role throughout Thomas Sidney Cooper's professional life. Following his first exhibition there in 1833, he became a fixture at its annual summer exhibitions. Election to the Academy represented the pinnacle of artistic achievement and recognition in Britain during the 19th century.

Cooper's growing reputation and consistent quality led to his election as an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1845. This was a significant honour, marking him as one of the country's leading artists. Associateship was often a stepping stone to full membership.

In 1867, Cooper achieved the highest rank, being elected a full Royal Academician (RA). This prestigious title confirmed his status within the art establishment and brought additional privileges and responsibilities within the Academy. He remained an active RA, exhibiting regularly and participating in Academy affairs, for the rest of his exceptionally long life. His continuous presence at the RA exhibitions for nearly seven decades is a testament to his enduring popularity and artistic stamina. The RA provided the main platform through which Cooper reached his audience and solidified his legacy.

Philanthropy and Educational Legacy in Canterbury

Beyond his artistic achievements, Thomas Sidney Cooper was known for his generosity and commitment to his hometown of Canterbury. Having experienced poverty in his youth, he became a significant philanthropist later in life, contributing to various local causes and charities. He was particularly noted for acts of personal charity, such as distributing food and fuel to the poor of Canterbury, especially during the Christmas season. Some accounts suggest his personal contributions were occasionally mistaken for those of organized charities, highlighting the direct nature of his benevolence.

His most lasting contribution to Canterbury, however, was in the field of art education. In 1882, Cooper founded and endowed the Canterbury Sidney Cooper School of Art. This institution grew out of an earlier initiative from 1868 intended as a free school to provide art education for poor boys, established partly as a memorial to his mother. The school provided formal training in drawing, painting, and design, filling a vital need in the region.

The Sidney Cooper School of Art flourished and eventually evolved into the Canterbury College of Art. Over time, it merged with other institutions and is now part of the University for the Creative Arts (UCA), a major multi-campus university for art and design education in the UK. The original building, often still referred to as the Sidney Cooper Gallery, remains an important arts venue in Canterbury, hosting exhibitions and events, a living testament to Cooper's vision and generosity. One notable student of the school during Cooper's era was Mary Tourtel, who later gained fame as the creator of the beloved children's character Rupert Bear.

Later Life and Enduring Reputation

Thomas Sidney Cooper enjoyed an exceptionally long life and career, remaining active as a painter well into his nineties. He continued to live primarily in London but maintained strong ties to Kent, purchasing land near Canterbury and spending summers there, constantly sketching the landscape and animals he loved. His home at Vernon Holme, Harbledown, just outside Canterbury, became his rural retreat.

He published his autobiography, My Life, in 1890, providing valuable insights into his experiences and the Victorian art world. He continued exhibiting at the Royal Academy until the very end of his life. His final exhibits were shown posthumously in 1902.

Thomas Sidney Cooper died on February 7, 1902, at his home Vernon Holme, at the remarkable age of 98. He was buried in Canterbury, the city that shaped his youth and benefited from his later philanthropy. At the time of his death, he was one of the most venerable figures in British art, respected for his dedication, his technical skill, and his unwavering focus on the pastoral beauty of England.

Today, Cooper's paintings are held in numerous public collections, including the Tate Britain, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Royal Academy of Arts in London, and particularly the Beaney House of Art & Knowledge in Canterbury, which holds a significant collection of his work. His paintings also remain popular in the art market, appreciated for their technical quality and their evocative portrayal of a bygone rural era.

Conclusion: A Victorian Master of the Pastoral

Thomas Sidney Cooper carved a unique and enduring niche in British art history. As "Cow Cooper," he became synonymous with the peaceful depiction of cattle and sheep within idyllic English landscapes. His technical mastery, honed through self-teaching, continental influence (especially from Verboeckhoven and the Dutch school), and decades of dedicated practice, allowed him to render animals and nature with convincing realism and sensitivity.

His works resonated deeply with the Victorian public, offering a comforting vision of rural stability and harmony during a time of immense social and industrial change. While his subject matter remained consistent, his skill and sincerity earned him widespread acclaim, culminating in full membership of the Royal Academy. Beyond his canvas, his philanthropic efforts and the founding of the Sidney Cooper School of Art demonstrate a commitment to his community and to fostering future generations of artists. Spanning reigns from George IV to Edward VII, Cooper's exceptionally long life and career provide a remarkable link across the 19th century, leaving a legacy of beautifully crafted pastoral scenes that continue to charm viewers today.