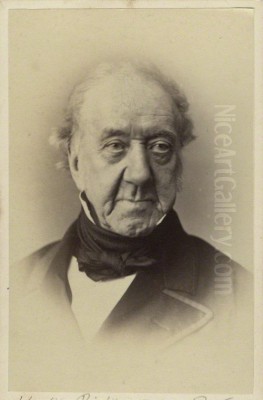

Henry William Pickersgill (1782-1875) stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th-century British art, particularly celebrated for his prolific output and skill as a portrait painter. Over a long and distinguished career, he captured the likenesses of many of the era's most notable personalities, leaving behind a valuable visual record of his time. His dedication to the Royal Academy of Arts and his consistent presence in its exhibitions cemented his reputation as a steadfast and respected member of the British artistic establishment.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born in Spitalfields, London, in 1782, Henry William Pickersgill's early life was connected to the city's thriving silk industry, his father being a silk manufacturer. It is noted that he was adopted by a Mr. Hall, also a silk manufacturer, who generously funded his education. Despite this background, young Pickersgill harboured a strong passion for drawing and painting from an early age. The Napoleonic Wars and the ensuing economic instability significantly impacted the silk trade, prompting Pickersgill to abandon his initial path in commerce and pursue his artistic ambitions with full commitment.

His formal artistic training began between 1802 and 1805 when he became a pupil of George Arnold ARA. Arnold, primarily a landscape and marine painter, would have provided Pickersgill with a foundational understanding of artistic principles, though Pickersgill himself would ultimately gravitate towards portraiture. This early exposure to landscape may have informed some of his later, less frequent forays into that genre.

The Royal Academy and Ascent to Prominence

In 1806, Henry William Pickersgill took a decisive step in his artistic career by enrolling as a student at the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. The Academy was, at this time, the epicentre of the British art world, and admission to its schools was a critical stepping stone for aspiring artists. Pickersgill proved to be a dedicated student and a consistent exhibitor at the Academy's annual exhibitions.

His talent and perseverance were recognized, leading to his election as an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1822. This was a significant honour, marking him as an artist of growing importance. Just four years later, in 1826, he achieved the distinction of becoming a full Royal Academician (RA), a testament to his established reputation and the high regard in which his work was held by his peers. This was an era when portraitists like Sir Thomas Lawrence, then President of the Royal Academy, dominated the field, and Pickersgill was carving out his own successful niche.

Throughout his long career, Pickersgill was an incredibly diligent contributor to the Royal Academy's exhibitions. It is recorded that he submitted an astounding 363 works for display, missing only three annual exhibitions over many decades. This consistent visibility kept his work in the public eye and reinforced his status within the artistic community.

Artistic Style and Influences

Pickersgill's artistic style is primarily characterized by its competence, clarity, and a certain refined sensibility, particularly in his portraiture. He possessed a keen ability to capture a sitter's likeness with accuracy, often imbuing his portraits with a sense of dignity and composure. His brushwork was generally smooth and controlled, reflecting the prevailing academic standards of the time. While perhaps not possessing the flamboyant brilliance of Sir Thomas Lawrence, or the psychological depth of later portraitists, Pickersgill's work was highly valued for its reliable quality and its faithful representation of his subjects.

The influence of Lawrence, the leading portrait painter of the Regency and early Victorian periods, is discernible in Pickersgill's approach, particularly in the elegant posing of his sitters and the attention to the textures of fabrics and attire. There is speculation that Pickersgill may have even spent some time working in Lawrence's studio, which was a common practice for aspiring portraitists seeking to learn from the master.

His portraits aimed for a balance between faithful representation and a degree of idealization, presenting his sitters in a favourable light suitable to their station. He was adept at conveying the character of his subjects, though often with a degree of reserve typical of the era's formal portraiture. Unlike the more romantic or dramatic approaches of some contemporaries like Henry Fuseli or William Blake (who worked in very different veins), Pickersgill's strength lay in his straightforward, accomplished depiction of individuals.

Key Sitters and Notable Portraits

As a sought-after portraitist, Henry William Pickersgill painted a wide array of distinguished individuals from various walks of life, including politicians, writers, scientists, philanthropists, and members of the aristocracy. His clientele reflected the intellectual and social fabric of 19th-century Britain.

Among his most famous sitters was the poet William Wordsworth. Pickersgill's portrait of Wordsworth, now in the National Portrait Gallery, London, is one of the best-known images of the celebrated Romantic poet, capturing him in his later years with a thoughtful and dignified expression.

He also painted Robert Vernon, a significant art patron whose collection formed the nucleus of the Tate Britain's holdings of British art. Pickersgill's depiction of Vernon acknowledges his importance in the art world. Another notable literary figure he portrayed was Letitia Elizabeth Landon (L.E.L.), a popular poet and novelist of the period.

The philosopher and social reformer Jeremy Bentham was another prominent subject. Pickersgill's portrait of Bentham is a significant historical document, capturing the likeness of one of the era's foremost thinkers. He also painted scientists such as the geologist William Buckland and the engineer George Stephenson, known as the "Father of Railways." These portraits underscore the era's respect for scientific and industrial advancement.

Other sitters included figures like the philanthropist Elizabeth Fry, the statesman Lord Hill, and numerous other military figures, academics, and society personalities. The sheer volume of his commissioned work speaks to his sustained popularity and the trust placed in his ability to deliver satisfactory and distinguished likenesses. His work can be compared to that of other successful portraitists of the period such as Martin Archer Shee, who also served as President of the Royal Academy, and Thomas Phillips, a notable rival.

Beyond Portraiture: Other Artistic Pursuits

While portraiture was undoubtedly the cornerstone of Henry William Pickersgill's career and reputation, he did occasionally venture into other genres. His early training with George Arnold, a landscape painter, likely instilled in him an appreciation for landscape, and he did exhibit some landscape works throughout his career. However, these were far less numerous than his portraits and did not achieve the same level of recognition.

Pickersgill also produced what were known as "fancy pictures." These were often sentimental, historical, or literary scenes, sometimes with an exotic or orientalist flavour, which were popular with the Victorian public. Examples include "The Oriental Love Letter" and "Nourmahal, the Light of the Harem." These works allowed for a greater degree of imaginative freedom than the constraints of formal portraiture. While these works demonstrated his versatility, they remained secondary to his primary focus. Artists like William Etty, known for his historical and mythological nudes, or Daniel Maclise, with his grand historical canvases, were more dedicated to these narrative genres.

Contemporaries: Collaboration and Rivalry

The art world of 19th-century London was a vibrant and competitive environment. Pickersgill navigated this world with considerable success. His relationship with Sir Thomas Lawrence was likely one of admiration and influence, and possibly some level of informal mentorship if he indeed worked in Lawrence's studio.

His most direct competitor in the field of portraiture was Thomas Phillips RA. Both artists catered to a similar clientele and were respected members of the Royal Academy. After Phillips's death in 1845, Pickersgill's position as one of the leading portrait painters of the older generation was further consolidated, though new talents were constantly emerging.

Pickersgill also had family connections within the art world. His cousin, Frederick Richard Pickersgill RA, was a notable historical painter and illustrator, known for works with literary, mythological, and biblical themes. While their primary genres differed, they were part of the same artistic milieu. Henry William's own son, Henry Hall Pickersgill (1812–1861), also became a painter, following in his father's footsteps and exhibiting a similar style, though his career was cut short by his earlier death.

During Pickersgill's long career, he would have witnessed significant shifts in artistic taste and practice. He worked alongside academicians like Sir Charles Lock Eastlake, who became President of the Royal Academy and Director of the National Gallery, and saw the rise of popular artists like Sir Edwin Landseer, famed for his animal paintings. Towards the end of his active career, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, including figures like John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt, began to challenge academic conventions, introducing a radically different aesthetic. Pickersgill, however, remained largely true to the established traditions in which he had been trained.

Later Career, Royal Academy Service, and Legacy

Henry William Pickersgill's commitment to the Royal Academy extended beyond merely exhibiting his works. In 1856, he was appointed Librarian of the Royal Academy, a position of trust and responsibility that he held for many years. This role involved overseeing the Academy's valuable collection of books and prints, further integrating him into the institution's daily life and governance.

His long service and consistent contributions were recognized in 1872 when he was made an Honorary Retired Academician. He passed away on 21 April 1875, at the advanced age of 93, in his home in Blandford Square, London. His life spanned a period of immense change in Britain, from the Napoleonic Wars through the bulk of the Victorian era.

Pickersgill's legacy is primarily that of a highly proficient and incredibly prolific portrait painter who provided a valuable visual record of many eminent figures of his time. His works are held in numerous public collections, most notably the National Portrait Gallery in London, which houses a significant number of his portraits. Other institutions, such as St Bartholomew's Hospital Museum and Archive, also hold examples of his work.

While art history has sometimes favoured more innovative or revolutionary artists, Pickersgill's contribution lies in his steadfast dedication to his craft and his role in documenting the society of his day. He was a master of the conventional portrait, delivering likenesses that satisfied his sitters and provided a dignified representation for posterity. His career exemplifies the successful academic artist of the 19th century, respected by his peers and sought after by patrons. He may not have been a radical innovator like J.M.W. Turner or John Constable, his RA contemporaries who revolutionized landscape painting, but within the realm of portraiture, he maintained a high standard of professionalism and skill for over half a century.

Conclusion: A Respected Chronicler of an Era

Henry William Pickersgill RA was a cornerstone of British portrait painting for much of the 19th century. His extensive oeuvre provides an invaluable gallery of the faces that shaped Victorian Britain. From poets and philosophers to scientists and statesmen, Pickersgill captured their likenesses with a skilled hand and a professional eye. His long association with the Royal Academy, as a student, exhibitor, Academician, and Librarian, underscores his deep integration into the artistic establishment of his time. While artistic tastes evolved dramatically over his lifetime, Pickersgill remained a consistent and reliable practitioner of a more traditional, yet highly accomplished, style of portraiture. His works continue to be important not only as artistic achievements but also as historical documents, offering insights into the personalities and appearances of a bygone era.