Henryk Szczygiński (1881–1944) stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of Polish art at the turn of the 20th century. A painter deeply rooted in the traditions of Polish Modernism, particularly the Young Poland (Młoda Polska) movement, Szczygiński carved a niche for himself with his evocative and emotionally charged landscapes. His work, characterized by a subtle interplay of light and shadow, a keen sensitivity to color, and a profound connection to the Polish countryside, offers a poetic vision of nature that continues to resonate with viewers. While perhaps not as internationally renowned as some of his contemporaries, his contribution to Polish art, especially in the realm of landscape painting, is undeniable and merits closer examination.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

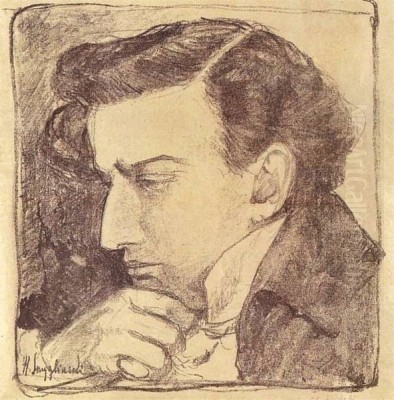

Born in 1881, Henryk Szczygiński came of age during a period of intense artistic and cultural ferment in Poland. Despite the nation's political subjugation, partitioned among three empires, Polish culture, and art in particular, served as a vital means of preserving national identity and fostering a sense of collective spirit. It was in this environment that Szczygiński embarked on his artistic journey.

His formal artistic education took place primarily at the Krakow Academy of Fine Arts, a crucible of talent and innovation at the time. This institution was a focal point for the Young Poland movement, which sought to break away from academic conservatism and embrace new forms of expression, often infused with Symbolism, Art Nouveau, and a renewed appreciation for folk traditions and the national landscape. In Krakow, Szczygiński had the invaluable opportunity to study under some of the most influential Polish artists of the era.

Among his most significant mentors was Jan Stanisławski (1860-1907), a master of landscape painting and a charismatic teacher. Stanisławski was a proponent of plein-air painting and encouraged his students to capture the fleeting moods and atmospheric effects of nature directly. His own small-format, intensely lyrical landscapes had a profound impact on a generation of Polish painters, and Szczygiński was a receptive student. From Stanisławski, he inherited a deep love for the Polish countryside, a sophisticated understanding of color, and the ability to imbue his scenes with palpable emotion.

Szczygiński's education was not limited to Krakow. He also spent time studying in Munich, another important artistic center in Europe, which would have exposed him to different artistic currents and techniques. However, it was the ethos of the Krakow Academy and the specific influence of figures like Stanisławski, and indirectly the broader artistic environment shaped by giants like Jacek Malczewski (1854-1929) with his distinctive brand of Polish Symbolism, and Stanisław Wyspiański (1869-1907), a polymathic genius excelling in painting, drama, and design, that most profoundly shaped his artistic vision. The emphasis on emotional depth, symbolic meaning, and the intimate portrayal of the native landscape became hallmarks of Szczygiński's developing style.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Themes

Henryk Szczygiński's artistic style is best described as a lyrical and atmospheric interpretation of landscape, deeply influenced by the tenets of Polish Modernism and Symbolism. His works are not mere topographical records but rather subjective responses to the natural world, filtered through his personal sensibility and artistic vision.

The influence of Jan Stanisławski is paramount. Like his master, Szczygiński often favored smaller canvases, which lent themselves to intimate and concentrated expressions of mood. He adopted Stanisławski's emphasis on capturing the "soul" of the landscape, focusing on the subtle nuances of light, color, and atmosphere that evoke a particular feeling or state of mind. His brushwork could be both delicate and expressive, capable of rendering the soft haze of twilight or the crisp air of a spring morning.

Szczygiński's color palette was often subdued yet rich, with a preference for harmonious tones that enhanced the poetic quality of his scenes. He was particularly adept at depicting nocturnes and crepuscular scenes – the transitional moments of dawn and dusk – where light is soft and forms meld into evocative silhouettes. These works often carry a strong Symbolist undercurrent, suggesting deeper meanings beyond the visible reality. The quietude and mystery of the night, or the melancholic beauty of autumn, became recurring motifs, allowing for a more introspective and emotional engagement with the landscape.

While Stanisławski was a primary influence, Szczygiński's art also resonates with the broader concerns of the Young Poland movement. This era saw artists turning inwards, exploring themes of national identity, spirituality, and the subjective experience of reality. Landscape painting, in this context, became a vehicle for expressing these concerns. The Polish landscape itself – its fields, forests, rivers, and villages – was imbued with symbolic significance, representing continuity, resilience, and the enduring spirit of the nation. Szczygiński’s works, with their focus on typically Polish vistas, participate in this tradition.

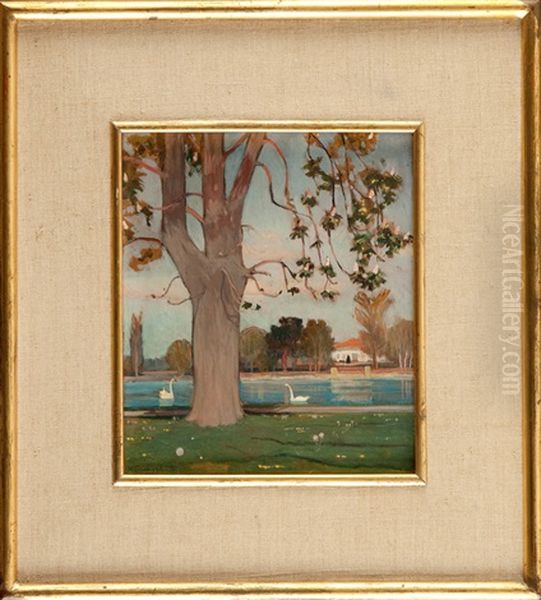

His subjects were often drawn from the immediate surroundings of Krakow and the Vistula River basin. The ancient town of Tyniec, with its historic Benedictine abbey perched on a limestone cliff overlooking the Vistula, was a favored motif, appearing in several of his paintings. These scenes are not just picturesque views but are imbued with a sense of history and timelessness. He also painted park scenes, capturing the cultivated beauty of urban green spaces, often with a focus on seasonal changes, such as the fresh greens of spring or the golden hues of autumn.

Representative Works

Several key works illustrate Henryk Szczygiński's artistic preoccupations and stylistic characteristics. While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné might be elusive, certain paintings stand out due to their exhibition history, presence in museum collections, or appearance in art market records.

One notable example is Galeria na Wiśle pod Tyńcem (Raftsmen on the Vistula near Tyniec), painted around 1904 and now housed in the National Museum in Warsaw. This work likely depicts the traditional timber rafts or barges navigating the Vistula River, with the distinctive silhouette of the Tyniec Abbey in the background. Such a scene would have allowed Szczygiński to explore the interplay of water, sky, and land, capturing the atmospheric conditions and the human element within the vastness of nature. The Vistula, Poland's principal river, has always held immense cultural and historical significance, and its depiction by artists like Szczygiński often carried symbolic weight.

A similar subject is found in Galeria na Wiśle w Krakowie (Raftsmen on the Vistula in Krakow), dated around 1900 and held in a private collection. This painting would focus on the river as it flows through or near the city, perhaps contrasting the natural elements with hints of urban life or historical architecture. The theme of river transport and the life of raftsmen was a common one in Polish art, offering a glimpse into traditional ways of life connected to the land and its waterways.

Another significant piece is Nocurnalny Wiosenny Landscape z Harbiellem (Spring Nocturne with Poplars – "Harbiellem" might be a specific location or a slight mistranscription, with "Topolami" meaning "with Poplars" being a common landscape feature), circa 1907, also in the collection of the National Museum in Warsaw. This title immediately signals Szczygiński's interest in nocturnal scenes and the depiction of specific seasons. A spring nocturne would offer opportunities to explore the soft, diffused light of the moon or early twilight, the fresh, burgeoning foliage of spring, and the slender, vertical forms of poplar trees, which often lend a melancholic or aspiring quality to landscapes. Such works are prime examples of his ability to create mood and evoke a sense of poetic mystery.

Auction records also provide glimpses into his oeuvre. A work titled WIOSNA W PARKU (Spring in the Park), an oil painting measuring 26.5 x 22.5 cm, was offered at auction in Warsaw in 2013. This piece, with its intimate scale, likely captured the delicate beauty of a park awakening in springtime, a theme that aligns perfectly with his known sensibilities. Another painting, simply titled Tyńec, an oil on canvas measuring 36.5 x 51 cm, further underscores his fascination with this iconic location. These works, though perhaps less documented than museum pieces, contribute to our understanding of his typical subjects and artistic approach.

These paintings, whether grander museum pieces or smaller, more intimate studies, consistently reveal Szczygiński's dedication to capturing the emotional essence of the Polish landscape. His focus on light, atmosphere, and the symbolic resonance of nature places him firmly within the tradition of lyrical landscape painting that flourished in Poland at the turn of the century.

Szczygiński in the Context of His Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Henryk Szczygiński's contribution, it is essential to view him within the vibrant artistic milieu of his time. The Young Poland period was exceptionally rich, populated by a diverse array of talented artists who were collectively redefining Polish art.

His teacher, Jan Stanisławski, was not just an individual influence but the leader of a veritable school of landscape painting. Many of Stanisławski's students, Szczygiński's peers, went on to become notable artists in their own right, each interpreting the master's lessons in their unique way. These included figures like Stanisław Kamocki (1875-1944), Stefan Filipkiewicz (1879-1944), and Henryk Uziembło (1879-1949), all of whom excelled in landscape painting, contributing to a distinctive Krakow school of landscape.

Beyond Stanisławski's immediate circle, the Krakow Academy was a hub for other major talents. Jacek Malczewski, with his powerful, allegorical paintings often featuring himself in various guises, was a towering figure whose influence extended beyond his direct students. His exploration of Polish history, mythology, and the artist's role in society provided a profound intellectual backdrop to the era. Józef Mehoffer (1869-1946), another leading figure of Young Poland, was known for his stunning stained-glass designs, intricate portraits, and decorative compositions, often infused with Art Nouveau elegance and Symbolist depth. Stanisław Wyspiański, perhaps the most versatile genius of the movement, excelled as a painter, playwright, poet, and designer, creating a uniquely Polish synthesis of arts and crafts. His portraits, landscapes, and monumental designs for Wawel Cathedral are iconic.

Leon Wyczółkowski (1852-1936), slightly older but a contemporary force, was another master landscapist and portraitist, known for his technical brilliance and his ability to capture the character of both people and places. His depictions of the Tatra Mountains, ancient trees, and historical architecture are celebrated. Wojciech Weiss (1875-1950), a contemporary of Szczygiński, initially embraced the expressive intensity of early Modernism and Symbolism, with emotionally charged portraits and landscapes, before his style evolved. His early works, in particular, share some of the melancholic and introspective qualities found in the art of the period.

Olga Boznańska (1865-1940), working primarily in Krakow and Paris, developed a highly personal, psychologically astute style of portraiture, often characterized by its subtle color harmonies and melancholic introspection, reflecting the broader Symbolist mood. Ferdynand Ruszczyc (1870-1936), active in Vilnius and Krakow, created powerful, often dramatic landscapes that conveyed a deep connection to the land and its history, sometimes with a more monumental feel than Szczygiński's intimate works. Konrad Krzyżanowski (1872-1922), associated with Warsaw, was known for his expressive, psychologically penetrating portraits and atmospheric landscapes, often with a darker, more dramatic palette.

While Szczygiński's focus remained primarily on lyrical landscape, he operated within this dynamic environment where artists explored various facets of Modernism, from Symbolism and Art Nouveau to early Expressionist tendencies. There would have been opportunities for interaction, shared exhibitions, and mutual, if indirect, influence. For instance, the Society of Polish Artists "Sztuka" (Art), founded in 1897, provided a crucial platform for these artists to exhibit their work and promote modern Polish art. Szczygiński, like many of his peers, would have been part of this broader artistic conversation.

Later, Polish art would see the rise of avant-garde movements like Formism, and groups such as "Blok," co-founded by artists like Henryk Stażewski (1894-1988), Mieczysław Szczuka (1898-1927), and Teresa Żarnower (1897-1949), who embraced Cubism, Suprematism, and Constructivism. While Szczygiński's art did not move in this abstract direction, his work represents an important phase of Polish Modernism that paved the way for subsequent developments by emphasizing artistic subjectivity and a departure from purely academic representation. Even the singular figure of Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, "Witkacy" (1885-1939), with his wildly imaginative theories and artworks, emerged from this fertile ground of Polish Modernism.

Szczygiński's relationship with Jan Stanisławski was clearly one of student and revered master. There is no specific record of direct collaborations with other major figures in the manner of joint projects, but the shared artistic climate, common exhibition venues, and the relatively close-knit nature of the Krakow art scene would have ensured a degree of mutual awareness and likely informal interaction. His artistic path was one of personal refinement within the landscape tradition championed by Stanisławski, contributing his distinct voice to the chorus of Polish Modernist painters.

Market Presence and Legacy

Assessing the market value and auction history of an artist like Henryk Szczygiński provides insights into his posthumous recognition and the desirability of his work among collectors. While not reaching the stratospheric prices of some of his more famous contemporaries, Szczygiński's paintings appear regularly on the Polish art market and occasionally internationally, indicating a consistent, if modest, level of appreciation.

The auction records mentioned earlier offer a snapshot. The painting WIOSNA W PARKU had an estimate of €2,400 to €3,300 in a 2013 Warsaw auction. Another work, Tyńec, was estimated at 10,000 to 14,000 Polish Złoty (PLN) in a different sale. A further piece was listed with an estimate of 3,000 to 15,000 PLN. These figures suggest that his smaller to medium-sized oil paintings typically command prices in the range of a few thousand to several thousand euros or their equivalent in PLN, depending on size, subject matter, condition, and provenance.

Interestingly, one provided piece of information mentions a significantly higher figure: a "third piece" (unspecified title or details in the prompt's summary) reportedly achieved a price of RMB 920,000. If this refers to a work by Henryk Szczygiński the painter (1881-1944), this would be an exceptionally high price, equivalent to over €100,000 or well over 400,000 PLN, depending on the exchange rate at the time of sale. Such a price would suggest a particularly important, large, or historically significant work, or perhaps a sale in a market with different valuation dynamics. Without further details on this specific transaction, it stands as an outlier compared to the more commonly observed price range but indicates the potential for certain works to achieve high values.

The continued presence of his works in museum collections, notably the National Museum in Warsaw, ensures his legacy within the official narrative of Polish art history. His paintings serve as important examples of the lyrical landscape tradition that was a key component of the Young Poland movement. For collectors of Polish art, particularly those specializing in this period, Szczygiński's works offer an opportunity to acquire pieces that are both aesthetically pleasing and historically significant, representing a specific and influential current within Polish Modernism.

His legacy lies in his contribution to the rich tradition of Polish landscape painting. He successfully absorbed the lessons of his master, Jan Stanisławski, and developed a personal style characterized by its sensitivity, emotional depth, and poetic interpretation of nature. His paintings of the Vistula, Tyniec, and the changing seasons capture a particular vision of the Polish countryside, imbued with a quiet lyricism that continues to appeal. While he may not have been a radical innovator in the vein of later avant-garde artists, his dedication to his craft and his ability to convey the subtle moods of nature secure his place as a respected artist of the Young Poland era.

Conclusion

Henryk Szczygiński (1881-1944) was an artist whose life and work were intrinsically linked to a pivotal period in Polish art history – the Young Poland movement. Educated at the Krakow Academy of Fine Arts under the influential Jan Stanisławski, he became a skilled practitioner of lyrical landscape painting, a genre that allowed for profound emotional and symbolic expression. His canvases, often intimate in scale, captured the fleeting beauty of the Polish countryside, with a particular fondness for nocturnes, seasonal transitions, and iconic locations like Tyniec and the Vistula River.

His art, characterized by subtle color harmonies, atmospheric depth, and a poetic sensibility, reflects the broader Symbolist and Modernist currents of his time. While working alongside giants such as Jacek Malczewski, Stanisław Wyspiański, and Leon Wyczółkowski, Szczygiński maintained his distinct focus, contributing to the rich diversity of Polish art at the turn of the 20th century. His paintings, found in national collections and appearing on the art market, continue to be appreciated for their quiet beauty and their sensitive evocation of place and mood. Henryk Szczygiński remains a testament to the enduring power of landscape painting to convey not just the appearance of the world, but its soul.