Stanislaw Maslowski stands as a significant figure in the annals of Polish art, a painter whose life and work bridged the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in 1853 and passing away in 1926, Maslowski carved a distinct niche for himself, primarily as a master of Realist landscape painting, with a particular affinity for the delicate and expressive medium of watercolor. His canvases and paper works are imbued with a profound love for the Polish countryside, its changing seasons, and the everyday life of its inhabitants. While deeply rooted in the traditions of Realism, his art also subtly absorbed the shifting artistic currents of his time, including whispers of Impressionism and the burgeoning spirit of the Young Poland movement. This exploration will delve into his life, artistic journey, key works, and his position within the vibrant tapestry of Polish and European art.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Stanislaw Maslowski was born on December 3, 1853, in Włodawa, a town in eastern Poland, which at the time was part of Congress Poland under Russian rule. This geopolitical context is important, as Poland did not exist as an independent nation during much of Maslowski's life, and art often became a vessel for preserving national identity and cultural heritage. His family background, though not extensively documented in common sources, likely provided an environment where his nascent artistic talents could be recognized.

The pivotal moment in his formal artistic education came when he moved to Warsaw. There, he enrolled in the Warsaw School of Drawing (Szkola Rysunkowa). This institution was a crucial hub for artistic training in Poland, especially given the limited opportunities under foreign partition. At the Warsaw School of Drawing, Maslowski studied under the tutelage of influential Polish artists such as Wojciech Gerson and Aleksander Kamiński. Gerson, in particular, was a leading figure of Polish Realism, known for his historical paintings and landscapes, and he undoubtedly instilled in Maslowski a respect for meticulous observation and a dedication to depicting the national landscape. Gerson's emphasis on plein-air painting and direct study from nature would have a lasting impact on Maslowski's approach.

This period of study, roughly from 1871 to 1875, laid the foundational skills for Maslowski. He learned the principles of composition, color theory, and draughtsmanship, all essential for a career in Realist painting. The artistic environment in Warsaw, though perhaps not as cosmopolitan as Paris or Munich at the time, was nonetheless vibrant, with artists keenly aware of broader European trends while simultaneously striving to forge a distinctly Polish artistic voice.

Development of a Personal Style: Realism and Beyond

Following his formal training, Maslowski embarked on a path of refining his artistic vision. He was drawn to the landscapes of Poland, particularly the regions of Mazovia and Podolia, as well as undertaking painting expeditions to what is now Ukraine, which historically had strong cultural and artistic ties with Poland. These travels provided him with a rich tapestry of subjects: rolling fields, dense forests, tranquil rivers, and the rustic charm of village life.

Maslowski's primary allegiance was to Realism. He sought to capture the world around him with truthfulness and accuracy, shunning idealized or overly romanticized depictions. His landscapes are characterized by their careful attention to detail, their nuanced understanding of light and atmosphere, and their ability to evoke a specific sense of place and time. He was particularly adept at capturing the subtle shifts in light during different times of day and the distinct moods of the changing seasons. Spring, with its fresh greens and sense of renewal, and autumn, with its golden hues and melancholic beauty, were recurrent themes.

While Realism formed the bedrock of his style, Maslowski was not immune to the artistic innovations occurring around him. The late 19th century saw the rise of Impressionism, and while Maslowski never fully embraced the Impressionistic dissolution of form, his later works often show a brighter palette, a looser brushstroke, and a greater emphasis on capturing fleeting moments of light and color. This can be seen as a natural evolution of his plein-air practice, where direct observation of nature often leads to a more spontaneous and light-filled rendering.

He became particularly renowned for his mastery of watercolor. This challenging medium, with its demand for precision and its unforgiving nature, suited his ability to capture delicate atmospheric effects and luminous transparency. His watercolors are often characterized by their freshness, their fluid washes, and their ability to convey a sense of immediacy.

Key Themes and Subjects in Maslowski's Oeuvre

The Polish landscape was Maslowski's most enduring muse. He painted scenes of fields stretching to the horizon, often dotted with haystacks or figures of peasants at work. Rivers and ponds, reflecting the sky and surrounding foliage, were also favorite subjects. His depictions of forests capture both their grandeur and their intimacy, with sunlight filtering through leaves or snow blanketing the trees in winter.

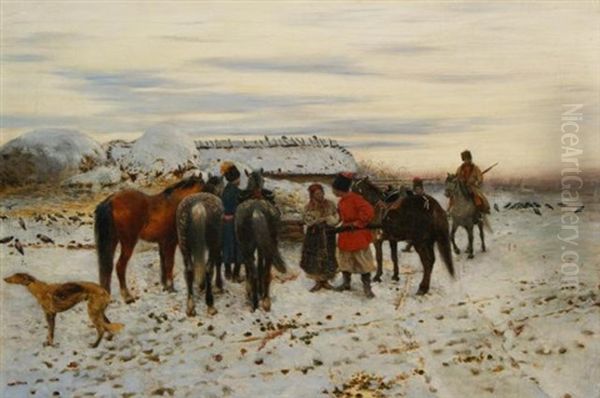

Beyond pure landscapes, Maslowski also engaged with genre scenes, depicting aspects of rural life. These were not grand historical narratives but rather quiet observations of everyday existence: farmers tilling the soil, women tending to livestock, or villagers gathered in market squares. These works often carry a sense of empathy and respect for the people whose lives were so intimately connected to the land.

A notable aspect of his work is his keen observation of nature's minutiae. He didn't just paint grand vistas; he was also interested in the specific textures of tree bark, the patterns of wildflowers in a meadow, or the way light catches on a water surface. This attention to detail lent an authenticity and intimacy to his paintings. His work often evokes a sense of tranquility and a deep connection to the natural world, reflecting perhaps a personal solace found in nature amidst the political turmoil of his times.

Representative Works and Their Significance

Several works stand out in Stanislaw Maslowski's oeuvre, showcasing his skill and thematic concerns.

"Buckwheat" (Gryka): This watercolor is perhaps one of his most famous and historically significant pieces. Depicting a field of blooming buckwheat, the painting is a testament to his ability to capture the delicate beauty of the Polish countryside. The work is rendered with a subtle palette and a keen eye for atmospheric perspective, conveying the expanse of the field under a soft, diffused light. The story of "Buckwheat" is also compelling. During World War II, the painting was looted by the Nazis, a fate shared by countless cultural treasures across Europe. For decades, its whereabouts were unknown. Remarkably, it resurfaced and, after verification by museum experts, was confirmed as the stolen artwork. It was subsequently returned to Poland and now resides in the National Museum in Warsaw, a symbol of cultural resilience and the enduring value of art.

"Moonrise" (Wschód księżyca): Painted in 1884, "Moonrise" is another iconic work that reveals a more poetic and perhaps even Symbolist-tinged aspect of Maslowski's art. The painting depicts a landscape bathed in the ethereal glow of the rising moon. It showcases his mastery in rendering nocturnal scenes, capturing the subtle gradations of light and shadow and evoking a mood of quiet contemplation and mystery. The work highlights his interest in the "curious amalgam of Earth and cosmos," suggesting a fascination with the sublime aspects of nature and perhaps a deeper, almost spiritual connection to the landscape. This painting demonstrates that while grounded in Realism, Maslowski was capable of imbuing his scenes with profound emotional and atmospheric depth.

Woodcarving of a Shepherd Boy and Dog (1882): Beyond his prolific output as a painter, Maslowski also explored other artistic mediums. An interesting example is a woodcarving he created in 1882, depicting a shepherd boy with a short-tailed dog. This piece is noted for its realistic portrayal of an early Polish Lowland Sheepdog (Polski Owczarek Nizinny, or PON). The work is considered a valuable historical record of the breed's appearance at the time. It also connects to the social and economic changes occurring in regions like Lublin, where traditional sheep farming, and consequently the specific breeds of herding dogs, were in decline. This piece shows Maslowski's observational skills extending beyond the canvas and his interest in the folk culture and rural traditions of Poland.

"Lark" (Skowronek): This painting, often cited among his important works, captures a quintessential scene of the Polish countryside – a peasant, perhaps pausing from his labor in the fields, listening to the song of a lark. It’s a simple yet evocative image, celebrating the harmony between man and nature, and the simple beauties of rural existence. The painting is noted for its bright, airy atmosphere and its sensitive portrayal of the figure within the landscape.

"Spring" (Wiosna): Maslowski painted numerous works depicting the arrival of spring, a theme beloved by many landscape artists. These paintings are typically characterized by fresh, vibrant colors, the depiction of melting snow, budding trees, and the overall sense of awakening and renewal in nature. They showcase his ability to capture the specific light and atmosphere of this transitional season.

These works, among many others, solidify Maslowski's reputation as a painter who could not only accurately represent the visual world but also infuse it with emotion and a distinct sense of Polish identity.

Maslowski in the Context of Polish and European Art

Stanislaw Maslowski's career unfolded during a dynamic period in Polish art. He was a contemporary of several other prominent Polish painters who also focused on Realism and landscape, though each developed their unique style. Artists like Józef Chełmoński were known for their dynamic and often dramatic depictions of Polish and Ukrainian landscapes, often featuring horses and scenes of peasant life. The Gierymski brothers, Maksymilian and Aleksander, were also key figures in Polish Realism, with Maksymilian known for his melancholic landscapes and hunting scenes, and Aleksander for his urban views of Warsaw and his exploration of light effects, sometimes bordering on Impressionism.

Leon Wyczółkowski was another towering figure, whose prolific career spanned Realism, Impressionism, and Symbolism, and who, like Maslowski, excelled in various techniques, including oil, pastel, and graphic arts. Julian Fałat, a master of watercolor, became famous for his winter landscapes and hunting scenes, often employing a technique that captured the crispness of snow and the stark beauty of the Polish winter.

As the 19th century drew to a close, the Young Poland (Młoda Polska) movement emerged, bringing with it a new wave of artistic expression that embraced Symbolism, Art Nouveau, and a renewed interest in Polish folklore and legend. Leading figures of this movement included Stanisław Wyspiański, a multifaceted artist known for his plays, stained glass designs, and paintings; Jacek Malczewski, whose works are rich in patriotic and mythological symbolism; and Józef Mehoffer, another versatile artist known for his monumental stained glass and Symbolist paintings. While Maslowski remained primarily a Realist, the artistic ferment of the Young Poland era undoubtedly influenced the broader cultural atmosphere in which he worked. His later works, with their increased attention to light and atmosphere, might reflect a subtle absorption of these newer sensibilities.

Internationally, Maslowski's commitment to Realism aligns him with broader European trends of the mid-to-late 19th century. The Barbizon School in France, with artists like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Jean-François Millet, had championed landscape painting and scenes of rural life, moving away from academic Neoclassicism. Later, Impressionists like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro took the depiction of light and atmosphere to new heights. While Maslowski did not become an Impressionist, his dedication to plein-air painting and his sensitivity to light show a shared concern with capturing the transient effects of nature.

His participation in exhibitions, such as the one organized by the Vienna Künstlergenossenschaft (Association of Austrian Artists) in 1908, indicates his engagement with the wider European art scene. Vienna at this time was a major cultural capital, home to artists like Gustav Klimt and the Vienna Secession, though the Künstlergenossenschaft represented a more traditional stream of art. Exhibiting there would have provided Maslowski with exposure and an opportunity to see his work in the context of other European artists.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Stanislaw Maslowski continued to paint throughout his life, remaining dedicated to his chosen themes and his meticulous approach to art-making. He passed away on May 31, 1926, in Warsaw. By the time of his death, the art world had already seen the rise of various avant-garde movements, from Fauvism and Cubism to Expressionism. Yet, Maslowski's contribution within the realm of Polish Realism remains significant.

His legacy lies in his authentic and heartfelt portrayal of the Polish landscape and its people. In a period when Poland's national identity was under threat, artists like Maslowski played a crucial role in preserving and celebrating the country's cultural heritage through their depictions of its natural beauty and traditional way of life. His mastery of watercolor set a high standard, and his works continue to be admired for their technical skill, their lyrical quality, and their evocative power.

His paintings are held in major Polish museums, including the National Museum in Warsaw and the National Museum in Krakow, as well as in private collections. They serve as a visual record of a bygone era and as a testament to an artist who found profound beauty in the familiar landscapes of his homeland. The story of his painting "Buckwheat," lost and then recovered, adds a poignant chapter to his legacy, highlighting the vulnerability of art in times of conflict and the enduring human effort to preserve cultural heritage.

The quiet dedication of Stanislaw Maslowski to his craft, his sensitive eye for the nuances of the natural world, and his ability to convey the soul of the Polish landscape ensure his place as an important and beloved figure in Polish art history. His work continues to resonate with viewers who appreciate the timeless beauty of nature captured through the vision of a skilled and soulful artist. He may not have been a radical innovator in the vein of some of his more avant-garde contemporaries, but his steadfast commitment to his artistic principles and his profound connection to his subject matter created a body of work that is both historically significant and aesthetically pleasing. His influence can be seen in subsequent generations of Polish landscape painters who continued to explore the national scenery with similar dedication and love.