Jan Stanislawski stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of Polish art history. Active during a transformative period, he was a leading exponent of Modernism and the Young Poland movement, renowned both for his evocative landscape paintings and his influential role as an educator. His life (1860-1907) spanned a crucial era of artistic change in Europe, and his work uniquely synthesized international trends with a deeply Polish sensibility.

Formative Years and Artistic Awakening

Jan Stanislawski was born on June 24, 1860, in Vilshana (also known as Olszana), a town in the Cherkasy region of what is now Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire. His background was marked by intellectual and patriotic fervor; his father, Antoni Stanislawski, was a lawyer, poet, and translator who had been exiled to Russia for his patriotic activities. This environment likely instilled in the young Stanislawski a strong sense of cultural identity.

Initially, Stanislawski's path did not seem destined for art. He pursued mathematics studies in Warsaw. However, the pull towards the visual arts proved stronger. He began his formal art education in Warsaw, studying under the respected painter Wojciech Gerson, a key figure in 19th-century Polish Realism. This initial training provided him with a solid foundation in drawing and painting techniques.

Academic Foundations in Krakow and Paris

Seeking further development, Stanislawski moved to Krakow, a major cultural center for Poles. From 1883 to 1885, he attended the Krakow Academy of Fine Arts (Szkoła Sztuk Pięknych w Krakowie). There, he studied under figures like Władysław Łuszczkiewicz, absorbing the academic traditions prevalent at the time but also being exposed to the burgeoning artistic currents within Poland.

The lure of Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world in the late 19th century, was irresistible. Stanislawski arrived in Paris around 1885 and remained there for approximately five years, until about 1888 or slightly later. He enrolled in the studio of Émile-Auguste Carolus-Duran, a fashionable portraitist and influential teacher whose students included John Singer Sargent. This period was crucial for Stanislawski's artistic maturation, exposing him directly to the revolutionary movements transforming French art.

The Parisian Crucible: Impressionism and Beyond

His time in Paris coincided with the height of Impressionism and the emergence of Post-Impressionism. Stanislawski absorbed the principles of Impressionism, particularly its emphasis on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and atmosphere, and the use of pure, unmixed color applied with visible brushstrokes. The work of Claude Monet, in particular, seems to have resonated with him, influencing his approach to light and color, although there is no documented evidence of direct personal interaction between the two artists.

Stanislawski's engagement with Parisian art was not merely imitative. He selectively integrated Impressionist techniques into his evolving style. He was drawn to the immediacy and vibrancy of the French movement but filtered it through his own temperament and artistic heritage. His focus remained steadfastly on landscape, a genre he would explore with remarkable intensity and originality throughout his career.

Synthesizing Influences

Upon returning from Paris, Stanislawski began to forge a distinctive artistic identity. His style represented a synthesis of the modern techniques he had encountered in France, particularly the Impressionist concern for light and color, with the traditions of 19th-century Polish painting, which often carried romantic or patriotic undertones. He developed a particular affinity for capturing the essence of the Polish and Ukrainian countryside.

His approach combined elements of Naturalism – a faithful observation of nature – with the subjective interpretation characteristic of Impressionism and the burgeoning Symbolist movement. He sought not just to record the appearance of a landscape but to convey its mood, its soul, and his emotional response to it. This blend of observation and feeling became a hallmark of his work.

Return to Krakow: The Educator

Stanislawski eventually settled in Krakow, which was then under Austro-Hungarian rule but served as the spiritual and cultural heart of Poland. In 1897, his reputation and talent earned him a prestigious appointment as a professor at the Krakow Academy of Fine Arts, where he took charge of the landscape painting class. This marked the beginning of a highly influential teaching career. Some sources suggest he later became the Dean, highlighting his importance within the institution.

His arrival at the Academy injected new energy into its landscape painting department. He was not content with traditional, studio-bound methods. Instead, he championed a more direct and experiential approach to learning, profoundly shaping the next generation of Polish landscape painters.

Revolutionizing Landscape Pedagogy

Stanislawski was a charismatic and inspiring teacher who fundamentally changed how landscape painting was taught in Krakow. He strongly advocated for plein air painting – working outdoors, directly in front of the subject. He believed that only through direct observation could artists truly capture the nuances of light, color, and atmosphere that were central to his own art.

He encouraged his students to abandon the dry, academic formulas often taught in classrooms and instead to immerse themselves in nature. His teaching philosophy emphasized sensitivity, personal interpretation, and the development of an individual artistic voice. He organized outdoor painting excursions, taking his students into the countryside around Krakow and further afield, fostering a deep connection between the artists and the Polish landscape.

The Stanislawski School

His impact as an educator was immense. He gathered around him a large group of devoted students who were deeply influenced by his methods and artistic vision. This group is sometimes referred to as the "Stanislawski School" of landscape painting. While not a formal school, it represented a shared approach characterized by vibrant color, sensitivity to light, and an intimate engagement with nature, often expressed in small, intensely focused compositions.

Many of his students went on to become significant artists in their own right, carrying forward his legacy and contributing to the richness of Polish art in the early 20th century. His pedagogical innovations had a lasting effect on art education in Poland.

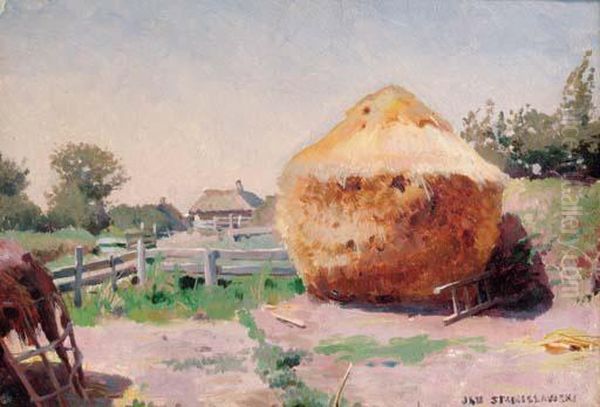

Core Artistic Philosophy: Capturing the Essence

Stanislawski's art is characterized by its focus and intensity. He predominantly worked in a small format, often painting on small wooden panels or cardboard. This intimate scale allowed him to concentrate on specific landscape motifs – a clump of trees, a single haystack, a fragment of sky, a rural structure – and invest them with remarkable presence and vitality.

His works are celebrated for their sense of space, light, and air. He possessed an exceptional ability to capture the specific quality of light at different times of day and under various weather conditions. His brushwork is often dynamic and expressive, conveying the texture and energy of the natural world. Despite their small size, his paintings often feel expansive and atmospheric.

Young Poland and Symbolism

Stanislawski was a central figure in the Młoda Polska (Young Poland) movement, the Polish variant of Art Nouveau and Symbolism that flourished around the turn of the 20th century. This movement sought to revitalize Polish culture and art, often drawing inspiration from folklore, nature, and national history, while embracing modern European artistic trends.

Within Young Poland, Stanislawski is considered one of the foremost landscape painters and a significant Symbolist. His landscapes often transcend mere depiction; they are imbued with mood, emotion, and sometimes a subtle symbolic resonance. He explored the expressive potential of color and light to convey feelings or spiritual ideas, aligning him with the Symbolist aim of suggesting deeper realities beyond surface appearances. He was seen as a bridge between Symbolism and early Expressionism in Polish art.

Mastery of Light and Color

Light was arguably Stanislawski's primary subject. He masterfully rendered the play of sunlight and shadow, the haze of morning mist, the glow of sunset, and the clear air of a summer day. His palette was typically bright and pure, using color not just descriptively but also emotionally and structurally. He employed bold color contrasts and subtle gradations to build form and create atmosphere.

His friend, the influential critic Zenon Przesmycki (Miriam), famously remarked that Stanislawski's landscapes "sing." This apt description captures the lyrical quality, the vibrancy, and the emotional resonance that characterize his best work. His paintings communicate a profound love and understanding of the natural world.

Signature Works

Among Stanislawski's most celebrated works are paintings like Barns in Ukraine (Stodoły na Ukrainie), painted after 1900, and Windmills (Wiatraki), likely dating from around 1904 (the date 1940 mentioned in one source is impossible, given his death in 1907). These works exemplify his mature style.

Barns in Ukraine likely depicts rustic farm buildings bathed in the strong light of the Ukrainian steppe, rendered with his characteristic vibrant color and atmospheric sensitivity. Windmills probably captures these structures as powerful silhouettes against the sky or integrated into the broad expanse of the landscape, perhaps symbolizing the forces of nature or the passage of time. Both works are housed in the National Museum in Krakow, testament to their importance in Polish art history.

A Hub of Artistic Life: Sztuka Society

Stanislawski was not only a creator and educator but also an active participant in the organizational life of Polish art. He was one of the founders and a key member of the "Sztuka" Society of Polish Artists (Towarzystwo Artystów Polskich "Sztuka"), established in Krakow in 1897.

"Sztuka" was a crucial exhibiting society that aimed to promote high standards in Polish art and showcase the best contemporary works, free from the constraints of the official academic salons. Its members included many of the leading figures of the Young Poland movement. Stanislawski's involvement underscored his commitment to advancing modern Polish art and fostering a community of like-minded artists.

Friendships and Collaborations: Józef Chełmoński

Stanislawski maintained important relationships with fellow artists. He shared a close friendship with Józef Chełmoński, another renowned Polish painter known for his dynamic depictions of Polish and Ukrainian landscapes, often featuring horses and peasant life. The two artists reportedly traveled together extensively, visiting Italy, Spain, France, Switzerland, Germany, and Austria, sharing experiences and likely influencing each other's perspectives.

They also collaborated, along with Julian Fałat and others, on a large-scale project: the Berezyna panorama, depicting a dramatic episode from Napoleon's retreat from Russia. This collaboration highlights the collegial atmosphere among some Polish artists of the period, even those with distinct styles.

Connections with Stanisław Wyspiański

Another significant figure in Stanislawski's circle was Stanisław Wyspiański, arguably the most versatile genius of the Young Poland movement – a painter, playwright, poet, and designer. Stanislawski and Wyspiański were friends, and the latter's powerful artistic vision and deep engagement with Polish history and identity likely resonated with Stanislawski. Living and working in the same vibrant Krakow milieu, their interactions contributed to the creative ferment of the era.

Peers in Young Poland: Wyczółkowski and Malczewski

Stanislawski's position within Young Poland is often discussed alongside Leon Wyczółkowski, another major landscape painter and graphic artist associated with the movement. Both artists were fascinated by light and nature, though their styles differed. Wyczółkowski also explored Tatra mountain landscapes and floral studies with great sensitivity.

Contextualizing Stanislawski also involves acknowledging Jacek Malczewski, the leading figure of Polish Symbolism. While Malczewski focused primarily on allegorical figure compositions laden with national and existential themes, his pervasive influence shaped the Symbolist atmosphere in which Stanislawski worked.

Krakow Academy Colleagues: Fałat and Axentowicz

At the Krakow Academy of Fine Arts, Stanislawski worked alongside other prominent artists. Julian Fałat, known for his watercolor landscapes and hunting scenes, served as the Academy's director for a period and was also involved with the "Sztuka" society. Teodor Axentowicz, a painter and rector of the Academy, known for his portraits and scenes of Hutsul life, was another important contemporary and colleague. This concentration of talent made the Krakow Academy a powerhouse of Polish art.

Other Contemporaries: Boznańska and Mehoffer

The artistic landscape also included figures like Olga Boznańska, a highly regarded painter known for her psychologically insightful portraits, who worked in both Krakow and Paris. Józef Mehoffer, a close friend of Wyspiański, was another key Young Poland artist, celebrated for his monumental stained-glass designs, murals, and paintings. These artists, along with Stanislawski, defined the character of Polish art at the turn of the century.

Wider Connections: Murashko and Stabrowski

Stanislawski's connections extended beyond the Krakow circle. The Ukrainian painter Olexandr Murashko, who also studied in Paris and was influenced by modern art, painted a well-known portrait of Stanislawski around 1905-1906. This portrait was exhibited in St. Petersburg in 1907, indicating Stanislawski's recognition beyond Poland.

While based in Krakow, Stanislawski was aware of developments elsewhere, such as the activities of Kazimierz Stabrowski, who co-founded the School of Fine Arts in Warsaw. Stabrowski's circle also attracted artists and writers, contributing to the broader Modernist movement in Poland, and potentially creating indirect links or influences.

The Landscape Miniaturist

Stanislawski's preference for small-format paintings is a defining characteristic. These were not sketches or studies in the traditional sense, but finished works, often executed with great precision and intensity. This approach allowed him to work quickly outdoors, capturing transient effects of light and weather. It also lent his works a jewel-like quality, demanding close attention from the viewer.

These small panels, sometimes numerous, could be seen as collectively forming a larger vision of the landscape – a mosaic of moments and observations that together conveyed the richness and diversity of nature. This method was integral to his artistic practice and contributed to the unique impact of his oeuvre.

Legacy: Shaping Polish Landscape Painting

Jan Stanislawski's influence on Polish art, particularly landscape painting, was profound and lasting. Through his own work, he demonstrated how modern European techniques could be adapted to express a distinctly Polish sensibility and a deep connection to the local landscape. He elevated landscape painting to a major genre within Polish Modernism.

His legacy as an educator is equally significant. The "Stanislawski School" produced a generation of landscape painters who continued to explore the possibilities of light, color, and plein-air painting. His emphasis on direct observation and personal expression left an indelible mark on art education in Krakow and beyond.

An Untimely End

Despite his significant achievements and influence, Jan Stanislawski's career was cut tragically short. He died in Krakow on January 6, 1907, at the age of only 46. His relatively early death meant that his artistic development was curtailed, leaving future generations to ponder what more he might have achieved.

Conclusion

Jan Stanislawski remains a celebrated figure in Polish art history. He was a master of the intimate landscape, capable of capturing the poetry and atmosphere of nature with exceptional skill and sensitivity. As a key member of the Young Poland movement, he helped define Polish Modernism, creating a unique synthesis of international trends and national spirit. His dual role as a groundbreaking artist and an inspirational teacher ensures his enduring importance. His vibrant, light-filled paintings continue to "sing" to viewers today, offering intimate glimpses into the soul of the Polish landscape.