Hilda Carline (1889-1950) was a British artist of considerable talent whose life and career were deeply intertwined with some of the most dynamic and challenging currents of early 20th-century British art. Born into a family steeped in artistic pursuits, her own journey as a painter and draughtswoman was marked by rigorous training, early promise, and the profound, often detrimental, impact of her personal relationships, most notably her marriage to the celebrated and eccentric painter Stanley Spencer. Despite periods of intense personal struggle that led to interruptions in her work, Carline produced a body of art, particularly in portraiture and drawing, that reveals a sensitive eye, technical skill, and a unique emotional depth. Her story is one of artistic dedication in the face of adversity, and a gradual, posthumous recognition of her distinct voice within a generation of remarkable British artists.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born in 1889, Hilda Carline was immersed in an artistic environment from a young age. Her family included other practicing artists, notably her brothers Sydney and Richard Carline, who also pursued careers in painting. This familial context undoubtedly nurtured her early inclinations towards the visual arts, providing a supportive, if perhaps at times competitive, backdrop for her developing talents. The early 20th century was a period of flux and excitement in the British art world, with traditional academicism being challenged by new European movements and a burgeoning modernist sensibility.

In 1913, seeking formal training, Carline enrolled at Percy Tudor-Hart's innovative art school in Hampstead. Tudor-Hart was known for his somewhat unconventional teaching methods, which often emphasized color theory and a more scientific approach to understanding visual phenomena, distinct from the more traditional academic training offered elsewhere. This period would have exposed Carline to contemporary ideas about art-making and provided her with foundational skills. Her studies, however, were soon to be interrupted by global events.

War Service and the Slade School of Fine Art

The outbreak of the First World War brought significant disruption to civilian life across Europe. Between 1916 and 1918, Hilda Carline served in the Women's Land Army, a civilian organization created to provide agricultural labor as men left for the front. This experience, shared by many women of her generation, would have offered a stark contrast to the sheltered world of art studios, exposing her to the rigors of physical labor and the broader societal impacts of the war. Such experiences often found their way, directly or indirectly, into the work of artists of this period.

Following her service, in 1918, Carline resumed her artistic education, this time at the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art in London. The Slade, under the formidable professorship of Henry Tonks, was a powerhouse of artistic training in Britain. Tonks, a surgeon by training before becoming a painter, was a demanding instructor known for his insistence on impeccable draughtsmanship and a deep understanding of anatomy and the Old Masters. He encouraged his students to emulate the meticulous drawing techniques of Renaissance artists, fostering a generation of skilled figurative painters. At the Slade, Carline would have been among a cohort of talented individuals, including figures who would go on to define British art in the coming decades, such as Stanley Spencer, whom she would later marry, and his brother Gilbert Spencer. Other notable artists associated with the Slade around this period or influenced by Tonks's teaching included Augustus John, Gwen John, William Orpen, and Mark Gertler, creating a vibrant and competitive atmosphere.

Early Career and Recognition

Hilda Carline's talent quickly became apparent. By 1921, her work was being exhibited at prominent London venues, including the London Group, the Royal Academy (RA), and the New English Art Club (NEAC). The London Group, formed in 1913, was a more progressive exhibiting society, often showcasing artists influenced by Post-Impressionism and other modern movements, with members like Roger Fry, Vanessa Bell, and Duncan Grant associated with it over time. The NEAC, while established as an alternative to the RA, had itself become a respected institution. To be exhibiting in these varied contexts so early in her career was a significant achievement and indicated a recognized level of skill and artistic maturity.

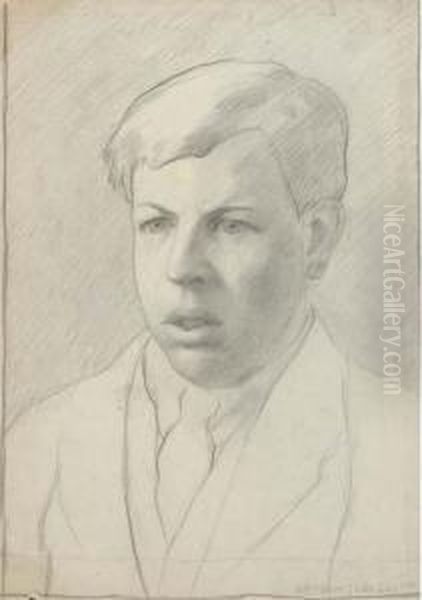

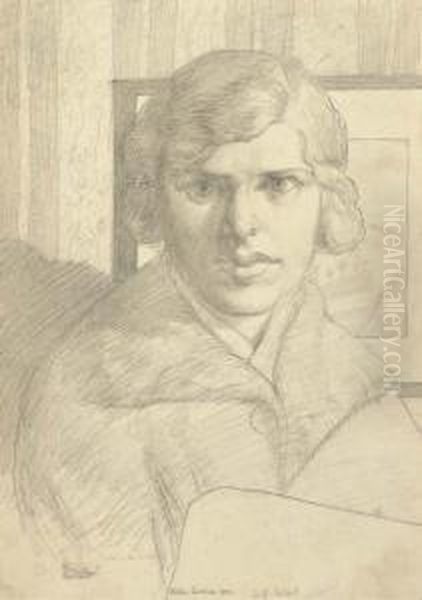

Her early work, particularly her portraiture, demonstrated the strong influence of Henry Tonks's teaching. She excelled in drawing, often using pencil and red chalk with great sensitivity and precision. Her portraits were not mere likenesses but sought to capture the inner character and emotional state of her sitters. The meticulous attention to form and subtle modeling evident in her drawings from this period reflect the rigorous Slade training. This initial success suggested a promising career lay ahead, placing her among the noteworthy emerging artists of the post-war generation.

Marriage to Stanley Spencer and its Profound Impact

In 1925, Hilda Carline married Stanley Spencer, a fellow Slade student who was already gaining a reputation as one of Britain's most original and visionary painters. Their relationship had begun during their time at the Slade. Stanley Spencer, known for his intensely personal and often religiously infused depictions of everyday life in his native village of Cookham, was a charismatic and complex individual. Their marriage, however, proved to be exceptionally turbulent and ultimately damaging to Hilda's artistic career and personal well-being.

The union has been described, perhaps dramatically but not without basis, as one of "British art history's most preposterous domestic soap operas." Stanley Spencer's artistic vision was all-consuming, and his personal life was unconventional, to say the least. He later developed an intense infatuation with Patricia Preece, leading to a complicated ménage à trois and eventually his divorce from Hilda in 1937, followed by his swift (and unconsummated) marriage to Preece. Throughout this period, Hilda's own artistic practice suffered immensely. The demands of her marriage, the emotional turmoil, and perhaps the overshadowing presence of her husband's burgeoning fame led to her almost ceasing to paint for a significant period.

This interruption is a poignant example of the challenges faced by many women artists, particularly those married to equally, or more famous, male artists. The societal expectations of the time often placed domestic responsibilities and the support of a husband's career above a woman's own professional aspirations. For Hilda, the intensity of Stanley Spencer's personality and the chaotic nature of their life together appear to have stifled her creative output for many years. Despite the divorce, Stanley Spencer reportedly continued to maintain some form of contact with Hilda, and his presence, even in absence, loomed large over her life.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Key Works

Hilda Carline's artistic style was primarily rooted in figurative realism, with a strong emphasis on draughtsmanship and a sensitive rendering of her subjects. The influence of Henry Tonks remained a cornerstone of her technique, particularly in her portrait drawings. She possessed a remarkable ability to capture not just the physical likeness but also the psychological presence of her sitters.

One of her notable early works is the Portrait of Gilbert Spencer (circa 1919). Gilbert, Stanley's brother and also an accomplished painter, was a frequent subject for artists in their circle. Carline created at least two portraits of him, one in pencil and another in red chalk. These works exemplify her skill in detailed rendering and her ability to convey personality through subtle expressions and posture, showcasing the meticulous approach championed by Tonks. The careful modeling of features and the delicate handling of line are characteristic of her best drawings.

Despite the near cessation of her painting during the most difficult years of her marriage, she did produce some significant pieces. The painting Elsie (1929) is mentioned as an important work from this period, suggesting that even amidst personal turmoil, moments of artistic activity occurred. This work is noted for reflecting her understanding of human emotion and, potentially, her engagement with religious themes, a preoccupation she shared with Stanley Spencer, though likely expressed in her own distinct manner.

Later in her life, particularly after her divorce and a subsequent period of recovery from a mental breakdown in 1942, Hilda Carline returned to art with renewed focus. Her later works included a series of drawings exploring religious themes. This return to art, and specifically to subjects of spiritual significance, might be interpreted as a way of processing her experiences and finding solace or meaning. Her style in these later drawings continued to emphasize emotional expression and a personal, introspective quality.

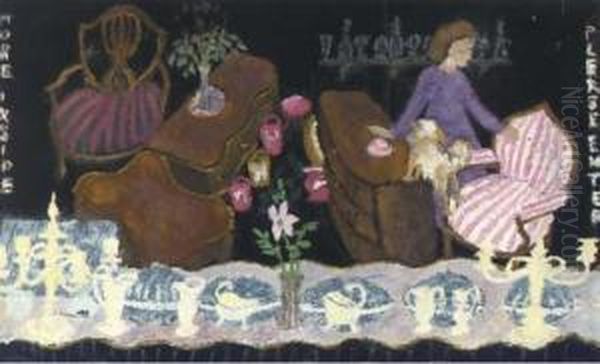

Her painting Gathering (1947) is considered one of her most important later works. While specific details about its subject matter are not provided in the initial information, a title like "Gathering" suggests a group scene, perhaps a collective portrait or a symbolic representation. Given its creation later in her life, it may encapsulate her mature style and thematic concerns, possibly reflecting on community, faith, or human connection after years of personal isolation and struggle. Her work, overall, is characterized by a sensitive handling of light and color, and a profound empathy for her subjects, whether in formal portraits or more thematic compositions. She shared with contemporaries like Meredith Frampton or Gerald Leslie Brockhurst a commitment to detailed realism, though her work often carried a more overt emotional charge.

The Hampstead Artistic Circle

During the 1920s, before her marriage fully consumed her, Hilda Carline was part of a vibrant artistic community in Hampstead, London. The Carline family home at 47 Downshire Hill became a regular meeting place for artists. These gatherings were informal salons, fostering discussion, camaraderie, and the exchange of ideas. Such circles were vital to the cultural life of London at the time, providing support networks and intellectual stimulation outside the formal structures of art schools and exhibiting societies.

Among the artists who frequented these gatherings were, naturally, Stanley Spencer, but also figures like James Wood and Henry Lamb. Henry Lamb, a painter associated with the Camden Town Group and later a respected portraitist and war artist, would have brought his own distinct artistic perspectives. James Wood, another contemporary, contributed to the mix of personalities and ideas. These interactions would have exposed Hilda to a range of artistic approaches and personalities, enriching her own understanding of the contemporary art scene. Her role in hosting or participating in these gatherings suggests a period of active engagement with her peers, a stark contrast to the later isolation that her marriage would bring. Artists like Dora Carrington, also Slade-trained and part of a complex artistic and personal network (the Bloomsbury Group), navigated similar social and creative milieus, though with different outcomes.

Later Years, Renewed Focus, and Personal Struggles

The period following her divorce from Stanley Spencer in 1937 was undoubtedly one of immense difficulty for Hilda Carline. The emotional toll of the preceding years culminated in a severe mental breakdown in 1942. Such experiences, while deeply personal and painful, can sometimes lead to periods of introspection and, for an artist, a potential reshaping of their creative vision.

It was after this crisis that Carline reportedly began to re-engage more consistently with her art, particularly through drawings with religious themes. This thematic shift is significant. For an artist who had been so closely associated with Stanley Spencer, whose own work was saturated with idiosyncratic religious imagery, Hilda's exploration of similar themes in her later years could be seen as both a continuation of a shared spiritual interest and an attempt to forge her own distinct path in expressing it. Her approach was likely more personal and less overtly narrative or eccentric than Stanley's, focusing perhaps on the solace and contemplative aspects of faith.

The creation of works like Gathering in 1947 indicates a significant return to her practice. This period, from the early 1940s until her death, represents a courageous reclamation of her artistic identity. Despite the profound setbacks, her innate talent and the deep-seated need to create resurfaced. Her later works, therefore, carry the weight of her life experiences, imbued with a maturity and emotional resonance that speaks of resilience.

Legacy and Reassessment

Hilda Carline died in 1950. For many years, her artistic contributions were largely overshadowed by the towering, and often controversial, figure of Stanley Spencer. This is a common fate for artists, particularly women, whose careers are linked with more famous male counterparts. However, in recent decades, there has been a concerted effort by art historians and curators to re-evaluate the contributions of artists previously marginalized or overlooked.

Hilda Carline's work has benefited from this reassessment. Her inclusion in exhibitions such as "Women Only Works on Paper" and publications like "Fifty Works by Fifty British Women Artists 1900 – 1950" are testaments to this growing recognition. These initiatives aim to highlight the unique perspectives and significant achievements of female artists who navigated the often challenging art world of the 20th century. Artists like Laura Knight and Dod Procter, who achieved considerable success in their lifetimes, or Gwen John, whose intensely personal and quiet art has gained increasing posthumous acclaim, form part of this broader narrative of British women artists whose contributions are now more fully appreciated.

Carline's art, with its blend of technical proficiency learned at the Slade and its deeply felt emotional content, offers a valuable insight into the British figurative tradition. Her portraits, in particular, stand out for their sensitivity and psychological acuity. The story of her life, while marked by personal tragedy and artistic interruption, also speaks to an enduring creative spirit. Her work provides a poignant counterpoint to the more bombastic narratives of some of her male contemporaries, offering a quieter but no less compelling artistic vision.

Conclusion

Hilda Carline's journey as an artist was one of early promise, profound personal challenges that led to a painful hiatus, and a courageous late resurgence. Her education under Percy Tudor-Hart and, more significantly, Henry Tonks at the Slade, equipped her with formidable skills in drawing and painting. Her early successes in London's exhibiting societies pointed towards a bright future. However, her tumultuous marriage to Stanley Spencer undeniably curtailed her artistic development for many years, a stark reminder of the personal sacrifices that have often been the price of admission for women in the art world.

Despite these immense difficulties, Hilda Carline's talent was undeniable. Her portraits, such as those of Gilbert Spencer, reveal a keen observational power and a delicate touch. Later works, including the enigmatic Gathering and her religious drawings, suggest a deepening introspection and a search for meaning in the aftermath of personal crisis. While the shadow of Stanley Spencer long obscured her own achievements, the ongoing reassessment of 20th-century British art is rightfully bringing Hilda Carline's sensitive and skilled work into the light. She remains an important figure, not only for the quality of her art but also as a representative of the often-unseen struggles and quiet triumphs of women artists of her generation, alongside figures like Evelyn Dunbar or Winifred Knights, whose careers also navigated the complexities of war, personal life, and artistic dedication. Her legacy is one of resilience, a testament to an artistic spirit that, though battered, ultimately endured.