Joseph Bernard stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the landscape of early 20th-century sculpture. A French artist whose life (1866-1931) bridged the twilight of 19th-century academicism and the dawn of modernism, Bernard carved out a unique niche for himself. He is particularly celebrated for his pioneering work in direct carving and his contributions to the emerging Art Deco style, creating sculptures that exuded a distinct blend of classical grace and modern sensibility. His journey from a stonemason's son to an influential sculptor offers a compelling narrative of artistic evolution and quiet innovation.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Vienne, a town near Lyon, France, in 1866, Joseph Bernard's artistic inclinations were perhaps preordained. His father was a stonemason, and young Joseph grew up surrounded by the craft of shaping stone. This early exposure to the material and its possibilities undoubtedly left an indelible mark on his artistic psyche. Unlike many of his contemporaries who might have come from more bourgeois backgrounds, Bernard's connection to the raw materials of sculpture was visceral and foundational.

His formal artistic training began at the École des Beaux-Arts in Lyon. Here, he would have been immersed in the traditional academic curriculum, which emphasized drawing from life, the study of anatomy, and the copying of classical and Renaissance masterpieces. This rigorous training provided him with a solid technical grounding in figure representation, modeling, and the principles of composition. Lyon, a significant provincial art center, offered a robust environment for a budding artist.

Following his studies in Lyon, Bernard, like many ambitious young artists of his generation, made his way to Paris, the undisputed art capital of the world. He enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the very heart of the French academic art establishment. However, reports suggest that his time in the Parisian institution was not marked by extraordinary distinction. It's plausible that the rigid doctrines of the academy, even as they were beginning to be challenged by avant-garde movements, did not fully resonate with Bernard's evolving artistic temperament. He reportedly found himself more drawn to painting and drawing during this period, perhaps seeking a more immediate or personal form of expression than the laborious processes of academic sculpture allowed.

Despite this, the academic training he received in both Lyon and Paris equipped him with the essential skills that would underpin his later, more innovative work. He mastered the human form, a prerequisite for any sculptor of his era, and gained a deep understanding of sculptural tradition, against which he would later subtly rebel.

The Influence of Rodin and the Path to Independence

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the figure of Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) loomed large over the world of sculpture. Rodin had revolutionized the medium, breaking away from the smooth, idealized surfaces of Neoclassicism and the often sentimental storytelling of academic sculpture. He infused his figures with an unprecedented emotional intensity, a sense of inner life, and a dynamic, often fragmented, surface that captured the play of light and shadow.

It was almost inevitable that a young sculptor like Joseph Bernard would fall under Rodin's powerful influence. The expressive force and psychological depth of Rodin's work, as seen in masterpieces like The Burghers of Calais or The Kiss, offered a compelling alternative to the staid conventions of the academy. Bernard's early works likely showed traces of this Rodinesque sensibility, characterized by a certain romanticism and an interest in capturing the human condition. Camille Claudel (1864-1943), Rodin's gifted collaborator and a formidable sculptor in her own right, also contributed to this milieu of expressive figuration.

However, Bernard was not content to remain a mere follower. While he absorbed the lessons of Rodin's dynamism and emotional power, he gradually began to seek his own artistic voice. This transition was not abrupt but rather a progressive evolution. He started to move away from the more overtly dramatic and often tormented figures of Rodin, seeking a quieter, more harmonious and elegant form of expression. This shift in direction, a subtle but firm assertion of his individuality, reportedly caused some discussion and even minor controversy within artistic circles, where allegiances and influences were closely scrutinized.

His developing style began to incorporate a sense of grace and agility, focusing on the inherent beauty of the human form in motion or repose, rather than on overt psychological turmoil. This marked a departure from the high Romanticism of Rodin and Claudel and hinted at a new direction, one that would lead him towards a more streamlined and modern aesthetic.

The Innovation of Taille Directe (Direct Carving)

One of Joseph Bernard's most significant contributions to modern sculpture was his embrace and championing of taille directe, or direct carving. This technique involved the sculptor working directly on the final material, typically stone or wood, without the intermediary stages of creating a full-scale clay or plaster model that would then be mechanically copied by assistants using a pointing machine.

In the academic tradition, sculptors often focused on modeling in clay, a malleable material that allowed for easy addition and subtraction. The finished clay model would then be cast in plaster, and this plaster version would serve as the definitive guide for carving in marble or for casting in bronze. Direct carving, by contrast, was a more intuitive and risky process. It required the artist to have a clear vision of the final form within the block of stone and to possess immense skill in wielding the hammer and chisel. Each blow was decisive, as material removed could not easily be replaced.

Bernard began to explore direct carving in earnest around 1905 and became particularly known for it in the 1920s. This approach was a conscious rejection of the perceived "indirectness" of academic methods and a return to what was seen as a more "honest" engagement with the material. It emphasized the unique qualities of the stone itself – its grain, its texture, its resistance – and allowed these properties to inform the final artwork.

This commitment to direct carving aligned Bernard with a broader movement in modern art that valued authenticity, immediacy, and truth to materials. It was a technique that would be famously adopted and pushed to new extremes by sculptors like Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957) and Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920), both of whom sought to simplify forms and reveal the essential nature of their subjects and materials. Bernard's earlier adoption of direct carving can be seen as prefiguring their more radical explorations. His approach, while still rooted in figuration, emphasized a simplification of form and a respect for the integrity of the block, qualities that would become hallmarks of much early modernist sculpture.

Defining Characteristics of Bernard's Style

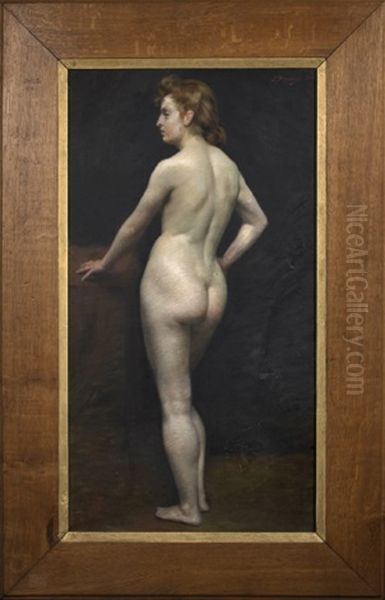

Joseph Bernard's mature style is characterized by a harmonious blend of elegance, rhythmic movement, and a subtle sensuality. His figures, often female nudes or dancers, possess a graceful agility and a sense of serene vitality. He was particularly adept at capturing the human body in moments of transition – walking, dancing, or in gentle contrapposto – conveying a sense of fluid motion and balanced form.

His sculptures often exhibit smooth, flowing surfaces, but unlike the polished perfection of Neoclassicism, Bernard's surfaces retain a sense of the artist's hand and the nature of the material, especially in his directly carved stone pieces. There is a lyrical quality to his work, a celebration of life and beauty that is neither overly sentimental nor starkly intellectual.

His approach can be seen as a bridge between the late Romanticism of Rodin and the emerging modernist sensibilities of artists like Henri Laurens (1885-1954) or Wilhelm Lehmbruck (1881-1919). While Laurens would move towards Cubist abstraction and Lehmbruck towards a more elongated, Gothic-tinged expressionism, Bernard maintained a connection to classical ideals of harmony and proportion, albeit reinterpreted through a modern lens. His figures are idealized yet retain a human warmth and accessibility.

Compared to contemporaries like Aristide Maillol (1861-1944), who also sought a return to classical calm and monumental simplicity, Bernard's figures often possess a greater sense of lightness and movement. Maillol's nudes are typically more static, embodying a sense of timeless, earthy monumentality. Antoine Bourdelle (1861-1929), another major sculptor of the era, often infused his work with an archaic grandeur and a more architectural structure. Bernard's art, while sharing some of their classicizing tendencies, carved its own path with its emphasis on rhythmic grace.

Key Works: Embodiments of an Artistic Vision

Several works stand out in Joseph Bernard's oeuvre, exemplifying his artistic concerns and technical mastery.

_Monument to Michael Servetus_ (1905-1911)

One of Bernard's most ambitious and renowned public commissions was the Monument to Michael Servetus, created for the town of Vienne (though sometimes cited as being for Annemasse, near Geneva, or with versions in different locations due to the controversial nature of Servetus). Michael Servetus was a 16th-century Spanish theologian and physician who was executed for heresy. The monument, a large-scale work, reportedly took Bernard several years to complete, largely working alone. This project demonstrated his capacity for sustained creative effort and his ability to handle monumental forms. The figure of Servetus, often depicted in a contemplative or defiant pose, allowed Bernard to explore themes of intellectual courage and martyrdom, rendered with a dignity and gravitas that befitted the subject. The execution of such a large piece, likely involving direct carving for significant portions, would have been a testament to his skill and dedication.

_Jeune fille à la cruche_ (Young Girl with a Pitcher) (c. 1910-1912)

This sculpture is perhaps one of Bernard's most iconic and frequently reproduced works. It depicts a young nude female figure, standing in a gentle, S-curved pose, holding a pitcher. The work epitomizes Bernard's mature style: the graceful lines, the harmonious proportions, the subtle play of volumes, and the serene expression. The surface is smooth yet alive, capturing the suppleness of youthful flesh. Young Girl with a Pitcher is a quintessential example of Bernard's ability to imbue a classical motif with a fresh, modern sensibility. It avoids academic stiffness and Rodinesque angst, instead offering an image of quiet beauty and timeless elegance. This piece, often cast in bronze but also existing in stone versions, showcases his mastery of form and his ability to convey a sense of gentle, rhythmic life.

Dancing Figures

Throughout his career, Bernard frequently returned to the theme of the dance. Works like La Danse or various studies of dancers capture the dynamism and fluidity of movement. These sculptures often feature figures in flowing, rhythmic poses, their limbs extended, their bodies arched or turning. In these pieces, Bernard explored the expressive potential of the human body in motion, celebrating its grace and energy. His dancers are not frenetic or wild, but rather embody a controlled, harmonious dynamism, reflecting his interest in balance and rhythmic composition. These works align with a broader early 20th-century fascination with dance, as seen in the paintings of Edgar Degas (though Bernard's approach was less about capturing a fleeting moment and more about embodying an idealized rhythm) or the revolutionary performances of Isadora Duncan.

Other works, including portraits and smaller figures, further demonstrate his consistent pursuit of formal elegance and refined craftsmanship. His oeuvre, taken as a whole, reveals an artist dedicated to the expressive power of the human form, interpreted through a lens of serene modernism.

Bernard and the Art Deco Movement

Joseph Bernard is widely recognized as one of the pioneers of the Art Deco style in sculpture. Art Deco, which flourished in the 1920s and 1930s, was characterized by its embrace of modernity, stylized forms, geometric patterns, rich materials, and a sense of streamlined elegance. It drew inspiration from a variety of sources, including Cubism, Fauvism, ancient Egyptian and Mesoamerican art, and the machine age.

Bernard's work from the 1910s and especially the 1920s aligns closely with the emerging Art Deco aesthetic. His simplification of forms, his emphasis on smooth, flowing lines, and the rhythmic, often symmetrical, compositions of his sculptures resonated with the style's core tenets. The elegant, elongated proportions and stylized grace of his figures, particularly his female nudes and dancers, became characteristic of Art Deco sculpture.

His commitment to direct carving also contributed to this connection. The process encouraged a certain simplification and stylization, as the artist worked to reveal the form inherent in the block of stone. This often resulted in sculptures that had a strong sense of volume and a clean, uncluttered silhouette – qualities highly valued in Art Deco design.

The landmark Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes held in Paris in 1925, from which the term "Art Deco" is derived, showcased this new style to the world. Bernard's work was featured in this exhibition, cementing his status as a key figure in the movement. His sculptures provided a figurative counterpoint to the more abstract and geometric tendencies within Art Deco, demonstrating how the human form could be reinterpreted with a modern, decorative sensibility without sacrificing its inherent grace. Sculptors like Demétre Chiparus (1886-1947), with his chryselephantine figures, or François Pompon (1855-1933), with his radically simplified animal sculptures, also contributed significantly to the sculptural dimension of Art Deco, each in their distinct way. Bernard's contribution was particularly notable for its fusion of classical poise with modern stylization.

Relationships with Contemporaries and Artistic Circles

Joseph Bernard navigated the vibrant and often competitive Parisian art world of the early 20th century, interacting with and being compared to many leading figures. His relationship with the legacy of Rodin was foundational, serving as both a point of departure and a standard against which new sculptural endeavors were often measured.

After Rodin's death in 1917, the art world looked for successors. Critics and fellow artists began to position Bernard alongside figures like Aristide Maillol and Antoine Bourdelle as one of the leading sculptors of the new generation. While Maillol emphasized a serene, classical monumentality and Bourdelle a more heroic, architectural force, Bernard offered a vision characterized by its lyrical grace and rhythmic elegance.

His innovative use of taille directe placed him in a lineage that would include Brancusi and Modigliani, both of whom made direct carving central to their practice. While Brancusi pushed towards radical abstraction and Modigliani developed his uniquely stylized, elongated figures, Bernard's earlier commitment to the technique helped pave the way for its wider acceptance as a legitimate and expressive modern sculptural method.

Bernard was also associated with influential critics and writers. André Salmon (1881-1969), a poet and art critic closely associated with Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) and the Cubist movement, was a notable admirer of Bernard's work. Salmon reportedly held Bernard in very high esteem, even suggesting his importance might surpass that of Rodin in certain respects – a bold claim that highlights the impact Bernard's quieter modernism had on perceptive contemporary observers.

Other sculptors active during this period, such as Charles Despiau (1874-1946), known for his sensitive and subtly modeled portraits and nudes, or Ossip Zadkine (1890-1967) and Joseph Csaky (1888-1971), who explored Cubist principles in sculpture, formed part of the rich artistic tapestry against which Bernard's career unfolded. While their styles differed, they all contributed to the dynamic evolution of sculpture in the early 20th century, moving away from 19th-century conventions towards diverse expressions of modernity.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Later Years

Joseph Bernard's work gained recognition through regular participation in major Parisian Salons, such as the Salon des Artistes Français, where he began exhibiting as early as 1892, and later at the Salon d'Automne and the Salon des Tuileries. These exhibitions were crucial venues for artists to showcase their work, engage with critics, and attract patrons.

He held his first solo exhibition in 1908, a significant milestone for any artist, indicating a growing reputation and a body of work substantial enough to command individual attention. His sculptures were acquired by museums and private collectors, both in France and internationally. The inclusion of his work in the 1925 Art Deco exposition was a major acknowledgment of his contribution to contemporary style.

The First World War (1914-1918) inevitably impacted his life and career. Reports indicate that Bernard suffered a stroke during the war, which temporarily halted his creative output. He gradually recovered and resumed his work, with some accounts suggesting a shift towards more personal or intimate pieces in his later years. Despite this setback, he continued to sculpt and exhibit, his reputation as a significant modern sculptor firmly established.

His work was appreciated for its refined aesthetic, its technical mastery, and its ability to synthesize classical ideals with a modern sensibility. He was seen as an artist who, while not as radically avant-garde as some of his contemporaries like Brancusi or the Cubist sculptors, nonetheless made a vital contribution to the evolution of the medium through his commitment to direct carving and his development of an elegant, streamlined figurative style.

Joseph Bernard passed away in 1931 in Boulogne-sur-Seine, near Paris, leaving behind a legacy as a sculptor who successfully navigated the transition from 19th-century traditions to 20th-century modernism.

Legacy and Art Historical Evaluation

In the annals of art history, Joseph Bernard is primarily valued for his role as a key transitional figure and an important proponent of direct carving. His influence on the Art Deco style is undeniable, with his elegant and stylized figures becoming emblematic of the movement's sculptural expression.

Art historians recognize his departure from Rodin's dramatic expressionism towards a more serene and harmonious aesthetic as a significant step in the diversification of modern sculpture. By embracing taille directe, he not only revived an ancient technique but also imbued it with a modern spirit, emphasizing truth to materials and a more intuitive, direct engagement between the artist and the medium. This approach had a profound impact on subsequent generations of sculptors, including Brancusi and Modigliani, who further explored its potential.

While perhaps not as widely known to the general public as Rodin, Maillol, or Brancusi, Bernard's contribution is well-respected within scholarly circles. His work is seen as embodying a particular strain of French modernism – one that valued elegance, craftsmanship, and a lyrical interpretation of the human form. He demonstrated that modernity in sculpture did not necessarily require a complete break with tradition or a full embrace of abstraction, but could also be found in a subtle refinement and reinterpretation of figurative art.

His sculptures continue to be admired for their timeless beauty and their quiet power. They can be found in major museum collections, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris and various regional museums in France, as well as in international collections. Joseph Bernard's legacy is that of an artist who, with integrity and skill, forged a distinctive path, enriching the sculptural landscape of the early 20th century with works of enduring grace and quiet innovation. He remains a testament to the enduring power of figurative sculpture to evolve and find new modes of expression in the modern age.