John Smart stands as one of the preeminent figures in the history of British miniature painting, an artist whose meticulous technique, keen eye for likeness, and prolific output defined the golden age of this intimate art form. Flourishing in the latter half of the 18th and the early 19th centuries, Smart's career spanned significant geographical and cultural shifts, from the bustling art scene of London to the vibrant courts of India. His work, characterized by its exquisite detail, subtle modeling, and warm tonalities, captured the personalities of a diverse clientele, leaving behind a rich visual record of his era. This exploration delves into the life, artistic style, significant works, and enduring legacy of John Smart, a craftsman of the highest order.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

The precise birth year of John Smart is a subject of minor historical debate, with sources variously citing 1741 or 1742. He was born in Norfolk, England, and it's important to distinguish him from a contemporary Scottish landscape painter of the same name. Smart's artistic talents emerged early. In 1755, at a young age, he demonstrated considerable promise by winning the second prize in a drawing competition for artists under fourteen, organized by the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (often simply called the Society of Arts). This early recognition was a significant stepping stone.

His formal training likely took place at William Shipley's drawing school in London, a crucible for many aspiring artists of the period. It was here that he would have encountered other talented youngsters, including Richard Cosway, who would become one of his chief rivals in the field of miniature painting. Indeed, in that 1755 competition, it was Cosway who secured the first prize. Despite this initial second place, Smart continued to hone his skills, winning further premiums from the Society of Arts in subsequent years, indicating a consistent development of his craft and a growing reputation. These early accolades provided a solid foundation for what would become a long and distinguished career.

The Indian Sojourn: A Decade of Distinction

Around 1785 (though some earlier accounts suggested 1760, modern scholarship leans towards the mid-1780s for his departure to India), John Smart made a pivotal decision to travel to India, a land that offered new opportunities and patronage. He settled in Madras (now Chennai), a major center for the British East India Company. For nearly a decade, Smart thrived in this new environment, becoming a highly sought-after portraitist. His sitters were a diverse group, ranging from influential members of the East India Company and British officials to Indian princes, nawabs, and their entourages.

During his time in India, Smart's style matured, retaining its characteristic precision while adapting to the rich visual culture and demands of his new clientele. His Indian portraits are renowned for their delicate rendering of features, intricate depiction of jewelry and costume, and the warm, often reddish-brown, backgrounds that became a hallmark of his work. He meticulously signed and dated many of his pieces, often with the initials "J.S." or "I.S." (as 'I' was often used for 'J' in Latin inscriptions) followed by the year, and sometimes "India" or "Madras." This practice has been invaluable for art historians in tracing his oeuvre and understanding his artistic development during this prolific period. His success in India was not only artistic but also financial, allowing him to build a considerable fortune.

Return to London and Continued Eminence

John Smart returned to London in 1795, his reputation enhanced by his successful tenure in India. He re-established himself in the competitive London art world, where the demand for miniature portraits remained strong. He resumed exhibiting his work, primarily at the Royal Academy of Arts, where he had shown pieces before his departure to India. While he was a consistent exhibitor at the Royal Academy, it's important to note his significant involvement with the Society of Artists of Great Britain. He had been a fellow of this society and served as its president in 1778, prior to his Indian journey.

Back in London, Smart continued to produce miniatures of exceptional quality. His style, while consistent in its meticulousness, showed a subtle evolution. His later works often display a slightly broader handling and a refined sense of color. He maintained a loyal clientele and attracted new patrons, competing effectively with other leading miniaturists of the day such as Richard Cosway, George Engleheart, and Ozias Humphry. His studio was a busy one, and he also trained pupils, including his son, John Smart Jr. (also known as John Smart II), who became a miniaturist in his own right, and his daughter, Anna Maria Smart, who also painted. He remained active as an artist until his death in London on May 1, 1811.

Artistic Style and Technique

John Smart's artistic style is defined by its extraordinary precision, delicate execution, and profound ability to capture a sitter's likeness and character. He primarily worked in watercolor on ivory, a support that had gained immense popularity among miniaturists in the 18th century due to its luminous quality, which imparted a lifelike glow to the flesh tones. Smart mastered this challenging medium, applying paint with a combination of fine stippling (dots) and hatching (short parallel strokes) to achieve subtle gradations of tone and smooth, almost enamel-like surfaces.

A hallmark of Smart's work is the warmth of his palette, particularly in the rendering of flesh. He often employed a characteristic reddish-brown for his backgrounds, which served to throw the figure into relief and create a sense of depth. This contrasted with the cooler, often ethereal blue backgrounds favored by some of his contemporaries, like Richard Cosway. Smart's attention to detail was legendary; every lace frill, every strand of hair, every subtle nuance of expression was rendered with painstaking care. Yet, this meticulousness rarely resulted in stiffness. His portraits possess a quiet vitality and psychological insight.

He had a profound understanding of facial anatomy, allowing him to model features with convincing three-dimensionality. His drawing was consistently accurate, forming the solid underpinning of his painted work. Unlike the more flamboyant and often flattering style of Cosway, Smart's approach was generally more direct and naturalistic, aiming for a faithful representation of the sitter. This commitment to verisimilitude, combined with his technical brilliance, ensured his enduring appeal. Other miniaturists like Samuel Shelley and Andrew Plimer, while highly skilled, each had their distinct stylistic traits, but Smart's consistent quality and recognizable technique set him apart.

Representative Works and Patronage

John Smart's prolific output means that a vast number of his miniatures survive today, housed in public and private collections worldwide. Due to the personal nature of miniatures, often commissioned as keepsakes or tokens of affection, many depict individuals whose identities are now lost. However, numerous portraits of identifiable figures attest to his distinguished clientele.

During his Indian period, he painted notable figures such as various officials of the East India Company and local rulers. Portraits like those of Sir John Dalling, Bt., Commander-in-Chief in Madras, or members of the family of the Nawab of Arcot, such as Umdat-ul-Umara, Nawab of Arcot, showcase his skill in capturing both European and Indian sitters with equal finesse, paying close attention to the details of their respective attires and insignia of rank. His portraits of Indian princes, such as Prince Abdul Ali Khan and Prince Abdul Khaliq Sultan, are celebrated for their sensitive portrayal and rich detail.

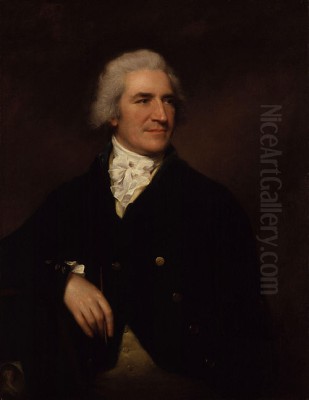

Upon his return to England, he continued to paint prominent members of society. Self-portraits by Smart also exist, offering a glimpse of the artist himself. One notable example is his Self-Portrait (circa 1797), which depicts him with a direct gaze, holding his porte-crayon, a testament to his profession. The sheer consistency of his output is remarkable; the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, for instance, holds an impressive collection that includes miniatures from almost every year of his active career, highlighting his unwavering dedication and skill. His patrons valued the truthfulness and refined elegance of his work, qualities that distinguished him from artists who might offer a more idealized or fashionable portrayal.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

John Smart operated within a vibrant and competitive artistic landscape, particularly in the specialized field of miniature painting. His most prominent contemporary and rival was Richard Cosway (1742-1821). Both artists trained around the same time and often vied for the same elite patronage. Cosway, known for his dashing style, fashionable portrayals, and flamboyant personality, presented a contrast to Smart's more reserved demeanor and meticulously detailed, naturalistic approach. While Cosway enjoyed the patronage of the Prince Regent (later George IV) and a glamorous circle, Smart appealed to those who valued precision and unadorned likeness.

George Engleheart (1750-1829) was another highly successful miniaturist of the era, known for his prolific output and slightly softer, more romantic style than Smart's. Ozias Humphry (1742-1810) also enjoyed considerable success, working in India for a period, like Smart, and later becoming Portrait Painter in Crayons to the King. Other notable miniaturists included Jeremiah Meyer (1735-1789), a founding member of the Royal Academy and a master of enamel miniatures as well as watercolor on ivory; Samuel Shelley (c.1750-1808), known for his graceful compositions and subject pictures in miniature; and the brothers Andrew Plimer (1763-1837) and Nathaniel Plimer (1757-1822), whose works are characterized by their large-eyed sitters and distinctively rich coloring.

The broader art world was dominated by figures like Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), the first President of the Royal Academy, and Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), whose large-scale oil portraits defined the Grand Manner. Miniaturists like Smart provided a more personal, portable, and intimate form of portraiture, highly valued in an age before photography. Smart also had connections with artists like Thomas Hickey (1741-1824), who also worked in India, and Tilly Kettle (1735-1786), one of the first British portrait painters to establish a successful practice in India. The influence of earlier miniaturists like Bernard Lens III (1682-1740), who helped popularize painting on ivory, also formed part of the tradition upon which Smart and his contemporaries built.

Legacy and Art Historical Re-evaluation

John Smart was highly esteemed during his lifetime, recognized for his exceptional skill and the consistent quality of his work. His miniatures were sought after by a discerning clientele who appreciated his ability to capture a true likeness with refined artistry. However, like many artists whose specialty fell out of mainstream fashion with the advent of photography in the 19th century, Smart's reputation, while never entirely extinguished, experienced a period of relative quietude.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, art historical scholarship has led to a significant re-evaluation and renewed appreciation of John Smart's contributions. Exhibitions dedicated to miniature painting and focused studies on individual artists have brought his work to a wider audience. Curators and collectors recognize the technical brilliance and historical importance of his oeuvre. His meticulous practice of signing and dating his works has greatly aided scholars in constructing a detailed understanding of his career and stylistic development.

Museums such as the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the National Portrait Gallery in London, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, hold significant collections of his miniatures. These collections demonstrate not only his technical mastery but also the breadth of his patronage, spanning British society and the colonial sphere in India. His work is seen as reflecting the 18th-century fascination with individual identity and the desire for personal mementos. The global reach of his practice, particularly his successful decade in India, also highlights the expanding horizons of British artists during this period of imperial growth.

Art historians now firmly place John Smart among the foremost miniaturists of any era. His dedication to his craft, his unwavering commitment to quality, and the sheer beauty of his surviving works ensure his enduring legacy as a master of the "little likeness."

Conclusion: An Enduring Master of Intimacy

John Smart's career exemplifies the pinnacle of miniature painting in the 18th century. From his early successes in London to his influential period in India and his esteemed later years, he maintained an exceptionally high standard of artistry. His miniatures are more than just small portraits; they are intimate windows into the lives and personalities of his sitters, rendered with a precision and sensitivity that few could match. His ability to convey character with such delicate means, on such a small scale, speaks to his profound talent and dedication.

While the art of miniature painting may have waned with the rise of new technologies, the work of its greatest practitioners, like John Smart, continues to fascinate and impress. His legacy is preserved in the hundreds of exquisite portraits that survive, each a testament to his skill, his eye for detail, and his significant contribution to the rich tapestry of British and Anglo-Indian art history. John Smart remains a celebrated figure, a quiet master whose delicate art speaks volumes about the people and the era he so meticulously documented.