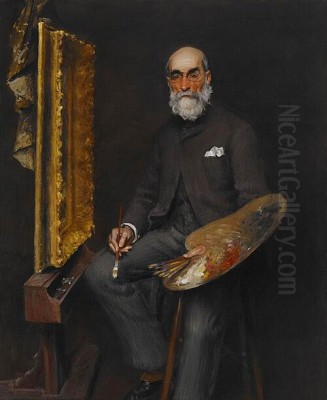

Thomas Worthington Whittredge stands as a significant figure in the history of American art, a leading painter associated with the second generation of the Hudson River School. His long and productive life, spanning from May 22, 1820, to February 25, 1910, witnessed dramatic changes in American society and art. Whittredge navigated these changes, evolving from early struggles and European training to become a celebrated interpreter of the American landscape, known for his serene woodland interiors, expansive plains, and sensitive handling of light. His journey reflects both the aspirations of nineteenth-century American artists and the shifting aesthetic currents of the time.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Born in a log cabin near Springfield, Ohio, Thomas Worthington Whittredge experienced a modest upbringing far removed from the established art centers of the East Coast. His family background offered little in the way of artistic encouragement, and his formal education was limited. Despite these humble beginnings, a passion for art took root early on. Seeking opportunities beyond the farm, the young Whittredge moved to the burgeoning city of Cincinnati at the age of seventeen.

In Cincinnati, Whittredge initially supported himself through practical trades, working as a house and sign painter. This hands-on experience likely provided a foundational understanding of pigments and application, common for many artists of the era. Concurrently, he began to pursue more formal artistic training, focusing initially on portraiture. While portrait painting offered a potential path to financial stability, Whittredge soon found his true calling lay in the depiction of landscapes, a genre gaining prominence in America. His early years in the Ohio Valley provided him with direct experience of the American wilderness, albeit different from the Eastern landscapes he would later become famous for painting.

Whittredge also attempted daguerreotypy for a brief period, reflecting the era's fascination with the new technology of photography. However, this venture proved unsuccessful, pushing him back towards painting. His early landscape efforts began to attract notice in Cincinnati, suggesting a burgeoning talent that required further cultivation. Recognizing the limitations of the local art scene, Whittredge, like many ambitious American artists of his generation, looked towards Europe for advanced training and exposure to the masterworks of the past.

European Sojourn: Düsseldorf and Rome

In 1849, Whittredge embarked on a decade-long journey to Europe, a pivotal period in his artistic development. His primary destination was Düsseldorf, Germany, home to the renowned Kunstakademie (Art Academy). The Düsseldorf Academy was a magnet for international students, including many Americans, known for its rigorous training methods emphasizing detailed drawing, meticulous finish, and often narrative or historical subjects. This contrasted sharply with the looser, more atmospheric approach gaining favor in Barbizon, France.

In Düsseldorf, Whittredge studied under various masters, but his most significant association was with Emanuel Leutze, a German-American historical painter. Leutze was then working on his monumental canvas, Washington Crossing the Delaware. Whittredge not only studied with Leutze but also posed for the figure of the steersman and, according to his autobiography, even for George Washington himself, providing a direct link to this iconic image of American history. This experience immersed him in the grand scale and historical themes prevalent in the Düsseldorf school.

During his time in Germany, Whittredge formed friendships with other artists, including the prominent German-American painter Albert Bierstadt. Bierstadt would later achieve fame for his dramatic, large-scale paintings of the American West, often exhibiting a style heavily influenced by their shared Düsseldorf training. Whittredge's own work during this period reflected the academy's influence, characterized by careful detail and somewhat darker palettes. However, he also traveled extensively, sketching in the Harz Mountains and along the Rhine, developing his skills in landscape observation.

Seeking broader artistic horizons, Whittredge eventually traveled to Italy, spending several years primarily in Rome. Rome offered a different atmosphere, steeped in classical antiquity and the legacy of Renaissance and Baroque art. It was also a gathering place for artists from various nations. Here, Whittredge continued to sketch landscapes, particularly in the Roman Campagna and the Alban Hills, often in the company of fellow artists. His time in Italy exposed him to different light conditions and landscape motifs, subtly beginning to temper the strictness of his Düsseldorf training. He associated with artists like Sanford Robinson Gifford, who would become a close friend and travel companion later in America.

Return to America and the Hudson River School

After ten years abroad, Whittredge returned to the United States in 1859, choosing New York City as his base. He arrived at a time when the Hudson River School, America's first major school of landscape painting, was flourishing. Founded by artists like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, the movement celebrated the beauty and grandeur of the American wilderness, often imbued with a sense of national pride and spiritual significance. Whittredge quickly integrated into this vibrant artistic community.

He established a studio in the famed Tenth Street Studio Building, a hub designed by Richard Morris Hunt that housed the studios of many leading artists of the day. His neighbors and colleagues included some of the most prominent figures in American art, such as Albert Bierstadt, Frederic Edwin Church, Sanford Robinson Gifford, and John Frederick Kensett. This environment fostered collaboration, friendly competition, and the exchange of ideas, placing Whittredge at the very center of the New York art world.

Whittredge became closely associated with the second generation of Hudson River School painters. While respectful of the pioneering work of Cole and Durand, this later generation often explored different aspects of nature and experimented with technique. Whittredge, influenced by his European experiences but committed to depicting American scenery, developed a style distinct from the highly dramatic, panoramic visions of Church or Bierstadt. He found his niche in more intimate, tranquil scenes, particularly woodland interiors and quiet streams.

His return marked a conscious shift away from the tighter, more narrative style associated with Düsseldorf. He found the prevailing American landscape style, though detailed, often possessed a greater sensitivity to atmospheric effects and the specific character of American light than what he had practiced in Germany. He embraced the Hudson River School's dedication to direct observation of nature, undertaking numerous sketching trips to the Catskills, the Adirondacks, and New England – the classic painting grounds of the school.

Artistic Style and Influences

Thomas Worthington Whittredge's mature artistic style represents a unique synthesis of American and European influences, adapted to his personal vision of the landscape. While firmly rooted in the Hudson River School tradition of detailed observation and reverence for nature, his work displays a distinct sensibility, often characterized by quietude, intimacy, and a sophisticated handling of light and atmosphere.

Upon returning from Europe, Whittredge consciously sought to shed the overt mannerisms of the Düsseldorf school, which he felt were less suited to the character of the American landscape. He admired the work of Asher B. Durand, particularly Durand's emphasis on truthful representation based on meticulous outdoor studies. However, Whittredge's style evolved beyond the detailed realism of the early Hudson River School. His European experience, particularly his exposure to the works of the French Barbizon School painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Théodore Rousseau (though perhaps indirectly), informed his approach.

The Barbizon influence is evident in Whittredge's preference for more intimate scenes, his softer brushwork in certain passages, and his focus on capturing specific moods and times of day through subtle tonal harmonies. He became particularly renowned for his depictions of forest interiors. Works like The Trout Pool (c. 1870) exemplify this genre, drawing the viewer into the cool, dappled light filtering through dense foliage, focusing on the textures of rocks, moss, and water. Unlike the expansive vistas favored by some contemporaries, these paintings offer a sense of quiet enclosure and contemplation.

Whittredge is also associated with Luminism, a tendency within mid-19th-century American landscape painting characterized by concealed brushwork, serene compositions, and a focus on the effects of atmospheric light. While perhaps not as central a Luminist figure as his friends Sanford Robinson Gifford or John Frederick Kensett, Whittredge masterfully employed light to define space and evoke mood. His depictions of coastal scenes, such as Third Beach, Newport (c. 1870-80), often feature calm waters, expansive skies, and a palpable sense of stillness, rendered with delicate gradations of tone.

His palette, initially influenced by the darker tones of Düsseldorf, brightened considerably after his return to America and particularly following his western travels. He became adept at capturing the clear, bright light of the American West, as well as the hazy, diffused light of the East Coast. Throughout his career, Whittredge maintained a commitment to careful drawing and structure, grounding his atmospheric effects in believable forms and spaces.

Journeys West: Expanding Horizons

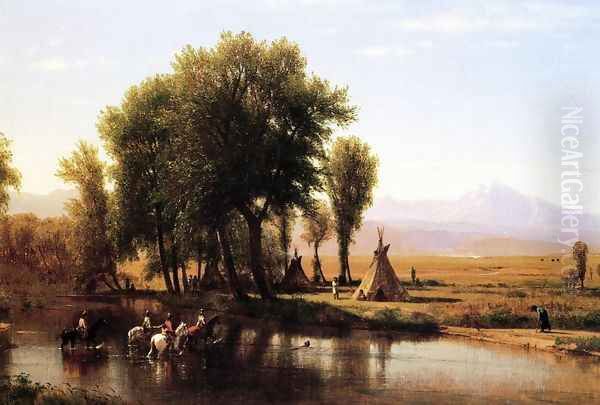

While Whittredge is often associated with the landscapes of the eastern United States, his travels to the American West in the mid-1860s and 1870 significantly impacted his art and broadened his subject matter. These journeys provided him with firsthand experience of vastly different terrains – the expansive Great Plains and the towering Rocky Mountains – which he translated into a distinct body of work.

His first major western expedition occurred in 1866 (often cited as 1865 for the start of the overall campaign planning, but the significant artistic journey was '66). He accompanied Major General John Pope on an inspection tour from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, across the plains to Denver and the Rockies, then south into New Mexico. This trip provided Whittredge with unparalleled access to landscapes few eastern artists had yet depicted. He traveled alongside Sanford Robinson Gifford and likely John Frederick Kensett for parts of this or related western journeys around this time, sharing the experience of sketching these new environments.

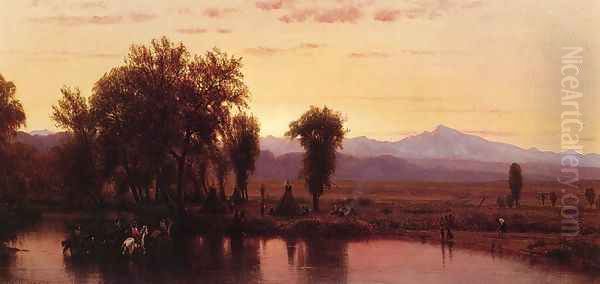

The vast, seemingly endless vistas of the Great Plains presented a compositional challenge entirely different from the enclosed forests or rolling hills of the East. Whittredge responded with paintings like Crossing the Platte (c. 1867-70), which capture the immense scale of the landscape, the quality of the light on the arid terrain, and the details of the journey, such as wagon trains or Native American encampments. These works often feature a lower horizon line and a dominant sky, emphasizing the flatness and breadth of the plains.

His experiences in the Rocky Mountains resulted in paintings depicting mountain scenery, though generally with less of the overt drama found in the works of Albert Bierstadt. Whittredge seemed more interested in the atmospheric effects and the play of light on the mountain forms than in emphasizing their sublime power. Works like On the Cache la Poudre River, Colorado (1871) show his ability to adapt his style to capture the specific character of the western landscape, including its unique light and vegetation.

Whittredge undertook subsequent, though perhaps less extensive, trips west, including one in 1870. These journeys provided him with a rich store of sketches and memories that he would draw upon for paintings created back in his New York studio for years to come. The western subjects added a significant dimension to his oeuvre, showcasing his versatility and his engagement with the expanding frontiers of the nation, a common theme in American art and culture of the period. His western pictures often possess a brighter palette and a more open sense of space compared to his eastern woodland scenes.

Mature Career and Recognition

Following his return from Europe and his integration into the New York art scene, Thomas Worthington Whittredge enjoyed a long and respected career. He became an active participant in the city's artistic institutions and gained significant recognition for his work, both from his peers and the public. His contributions extended beyond his own painting to encompass leadership roles within the art community.

In 1860, Whittredge was elected an Associate of the prestigious National Academy of Design (NAD), followed by his election as a full Academician in 1861 (some sources state 1862, but election often preceded formal induction). The NAD was the primary institution for artists in America at the time, hosting annual exhibitions that were major events in the cultural calendar. Whittredge exhibited regularly at the Academy throughout his career, showcasing his latest landscapes to critics and potential patrons.

His standing within the artistic community was further solidified when he served as President of the National Academy of Design for a term from 1874 to 1875 (some sources state 1875-1876, presidency terms could be complex). Holding this position underscored the high regard in which he was held by his fellow artists. It placed him at the forefront of the American art establishment during a period of growth and change.

Whittredge's work was also selected for inclusion in major national and international exhibitions. He served on the selection committees for important expositions, including the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876, a landmark event celebrating the nation's hundredth anniversary and showcasing American art and industry to the world. He also participated in juries for the Paris Universal Exposition. His involvement in these events highlights his role as a respected arbiter of taste and quality. His paintings were often awarded medals at these expositions, further cementing his reputation.

Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, Whittredge maintained his studio in the Tenth Street Studio Building, a vital period of production. He continued his sketching trips, gathering material for studio paintings that found ready buyers among the growing class of American collectors interested in native landscape subjects. His friendships with fellow artists like Jervis McEntee, another prominent landscape painter and studio neighbor, provided camaraderie and intellectual exchange. His works entered important private collections and gradually began to be acquired by public museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

Key Works and Themes

Thomas Worthington Whittredge's extensive body of work explores several recurring themes and includes numerous paintings now considered classics of American landscape art. While he painted a variety of subjects, certain motifs appear frequently, showcasing his particular artistic interests and strengths.

His woodland interiors are perhaps his most iconic and personal contributions. Paintings like The Trout Pool (c. 1870) and Forest Interior (various versions) capture the quiet solitude and intricate beauty of the eastern forests. These works are characterized by their careful rendering of foliage, rocks, and water, combined with a masterful handling of dappled sunlight filtering through the canopy. They invite contemplation and offer an intimate alternative to the grand panoramas often associated with the Hudson River School. This theme remained central throughout much of his mature career.

The landscapes derived from his western travels form another significant group. Crossing the Platte River (c. 1867-70) and On the Cache la Poudre River, Colorado (1871) represent his engagement with the vastness and unique light of the American West. These paintings often depict the interaction of human activity (wagon trains, Native American camps) with the immense scale of nature, reflecting themes of westward expansion and the encounter between different cultures. Indian Encampment on the Platte River (related titles exist) captures the atmospheric glow of sunset over the plains, blending landscape with genre elements.

Coastal scenes, particularly those painted around Newport, Rhode Island, where he often summered, represent another important facet of his work. Third Beach, Newport (c. 1870-80) exemplifies his ability to capture the tranquil beauty of the shoreline, often employing Luminist principles of calm composition and subtle light effects. These works contrast the enclosed spaces of his forests with the open expanses of sea and sky.

Whittredge also painted pastoral landscapes, often featuring meadows, haystacks, and gentle streams, reflecting the influence of the Barbizon school and his appreciation for cultivated, humanized landscapes alongside wilder scenes. Harvest Scene or Second Haying are examples that show a softer, more idyllic aspect of nature. A work like Camp Meeting (1874) combines landscape with genre, depicting a rural religious gathering, showcasing his interest in American life and customs within a natural setting.

Across these varied subjects, Whittredge consistently demonstrated his skill in rendering light and atmosphere, his strong sense of composition, and his deep connection to the American land. His works avoid overt moralizing or excessive drama, instead offering a more personal, poetic interpretation of nature.

Later Years and Legacy

In 1880, Thomas Worthington Whittredge moved from New York City to Summit, New Jersey, seeking a quieter life away from the bustling metropolis. He built a house on a hillside overlooking the town, where he would live and work for the remaining thirty years of his life. While removed from the daily interactions of the Tenth Street Studio, he remained active as a painter and maintained connections with the art world.

His later work continued to explore the themes that had defined his mature career, particularly the landscapes of the East Coast. He painted scenes around his New Jersey home, as well as revisiting favorite locations in the Catskills and New England. While the influence of Impressionism was growing in American art during this period, Whittredge largely maintained his established style, rooted in careful observation and atmospheric realism, though some later works show a slightly looser handling or brighter palette.

During his later years, Whittredge penned an autobiography, reflecting on his long life and career. Written with characteristic modesty and occasional humor, it provides invaluable insights into his experiences, his views on art, and his relationships with fellow artists like Emanuel Leutze, Albert Bierstadt, and Sanford Robinson Gifford. The manuscript remained unpublished during his lifetime but was eventually published posthumously by the Brooklyn Museum in 1942, becoming an important document for understanding nineteenth-century American art from an artist's perspective.

Thomas Worthington Whittredge died at his home in Summit, New Jersey, on February 25, 1910, at the age of 89. He was buried in Springfield, New Jersey. By the time of his death, the Hudson River School style was no longer dominant, having been largely superseded by Impressionism and other modern movements. However, Whittredge's reputation as a major figure of his era endured.

His legacy lies in his significant contribution to American landscape painting. He masterfully captured the diverse beauty of the American continent, from the intimate woodlands of the East to the vast plains of the West. His synthesis of American observation with European techniques, particularly the atmospheric sensitivity related to the Barbizon school and Luminism, resulted in a unique and enduring artistic vision. His works are held in major museum collections across the United States and continue to be admired for their technical skill, poetic sensibility, and evocative portrayal of nineteenth-century America. He stands as a key transitional figure, bridging the detailed realism of the early Hudson River School with the more atmospheric concerns that followed.

Conclusion

Thomas Worthington Whittredge's journey from an Ohio farm to the presidency of the National Academy of Design is a testament to his talent, perseverance, and adaptability. As a central figure in the second generation of the Hudson River School, he absorbed the influences of his predecessors like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, his European training under Emanuel Leutze in Düsseldorf, and the atmospheric aesthetics of the Barbizon school and Luminism. He forged a distinctive style characterized by serene woodland interiors, expansive western vistas, and a masterful handling of light.

His collaborations and friendships with contemporaries such as Albert Bierstadt, Sanford Robinson Gifford, and John Frederick Kensett placed him at the heart of the nineteenth-century American art world. His travels, particularly his expeditions to the American West, broadened the scope of landscape painting, capturing the unique character of the plains and mountains. Key works like The Trout Pool, Crossing the Platte, and Third Beach, Newport demonstrate his versatility and his profound connection to the American landscape. Whittredge's long career, respected position within artistic institutions, and his insightful autobiography solidify his importance. He remains a crucial figure for understanding the evolution of American art, celebrated for his quiet, poetic, and deeply felt interpretations of nature.