Jacob de Heusch stands as a notable figure within the rich tapestry of Dutch Golden Age painting, particularly recognized for his contributions to the Italianate landscape genre. Born in Utrecht in 1656 and passing away in 1701, his life and career bridged the artistic traditions of the Netherlands with the enduring allure of Italy, a path trodden by many Northern European artists seeking inspiration under Mediterranean skies. His work, characterized by idealized scenery, warm light, and often featuring classical ruins, reflects a deep engagement with both his Dutch heritage and the powerful influence of the Italian artistic environment.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Utrecht

Jacob de Heusch's artistic journey began in Utrecht, a significant artistic center in the Dutch Republic. His initial training was profoundly shaped by his familial connection to the art world. He was the nephew of Willem de Heusch, himself a respected landscape painter. It was under his uncle's tutelage that Jacob likely received his foundational skills in drawing and painting. Willem's own work often depicted Dutch or Italianate scenes, providing Jacob with an early exposure to the themes and styles that would come to define his career.

This apprenticeship within the family workshop would have grounded Jacob in the techniques and aesthetics prevalent in Dutch landscape painting of the period. Utrecht, in particular, had a history of artists looking towards Italy, known as the Utrecht Caravaggisti earlier in the century, like Gerard van Honthorst and Hendrick ter Brugghen, who brought dramatic chiaroscuro back from Rome. While Jacob de Heusch belonged to a later generation focused on landscape, this local tradition of Italian influence may have created a receptive environment for his later artistic development.

The training provided by Willem de Heusch would have emphasized careful observation, skillful composition, and the rendering of natural elements, albeit often within the somewhat more subdued light and atmosphere typical of Dutch landscapes compared to the sun-drenched Italian scenes Jacob would later favour. This early grounding provided the technical proficiency upon which he would build his distinct Italianate style.

The Transformative Journey to Rome

Around the year 1675, Jacob de Heusch embarked on a pivotal journey southward to Italy, specifically to Rome. This was a common practice for ambitious Northern European artists, who viewed Rome as the ultimate finishing school, a place to study classical antiquity firsthand and immerse themselves in the works of Renaissance and Baroque masters. For landscape painters, the Roman Campagna – the countryside surrounding the city – offered a wealth of inspiration with its rolling hills, ancient ruins, and distinctive Mediterranean light.

This experience proved transformative for de Heusch. The direct encounter with the Italian landscape, its classical remnants, and the works of artists who specialized in depicting it, profoundly redirected his artistic vision. He moved away from the style he had learned from his uncle, embracing a more idealized and atmospheric approach characteristic of the Italianate tradition. The warm, golden light of the south began to permeate his canvases, replacing the cooler tones often found in purely Dutch landscapes.

During his time in Rome, de Heusch was not isolated. He actively engaged with the artistic community, reportedly making friends and securing patrons. This network would have been crucial for his development, providing opportunities for commissions, intellectual exchange, and exposure to different artistic currents. His time in Italy was not merely about observing; it was about absorbing and integrating the spirit of the place into his art.

Membership in the Bentvueghels

A significant aspect of Jacob de Heusch's time in Rome was his association with the Bentvueghels (Dutch for "Birds of a Feather"). This was a society, or confraternity, primarily composed of Dutch and Flemish artists active in Rome. Founded in the 1620s, it served as a social and professional network for these expatriate artists, known for its bohemian character and initiation rituals where members received nicknames (bentnamen).

Becoming a member of the Bentvueghels indicates de Heusch's integration into the Netherlandish artistic community in Rome. While the specific details of his interactions within the group are not extensively documented in the provided sources, membership itself implies participation in their gatherings and likely professional camaraderie. The group included painters specializing in various genres, though landscape and genre scenes were particularly prominent among its members throughout its existence.

Notable artists associated with the Bentvueghels across different periods included figures like Cornelis van Poelenburgh, Bartholomeus Breenbergh, Jan Both, Andries Both, Herman van Swanevelt, Karel Dujardin, Nicolaes Berchem, and Johannes Lingelbach. While direct collaboration with de Heusch isn't specified, being part of this milieu meant exposure to a vibrant exchange of ideas and styles, all centered around the shared experience of being Northern artists working in the heart of the Italian art world. His travels with friends to Venice and other locations, mentioned in the source material, likely included fellow artists, possibly from this circle.

Artistic Style: Idealized Visions of Italy

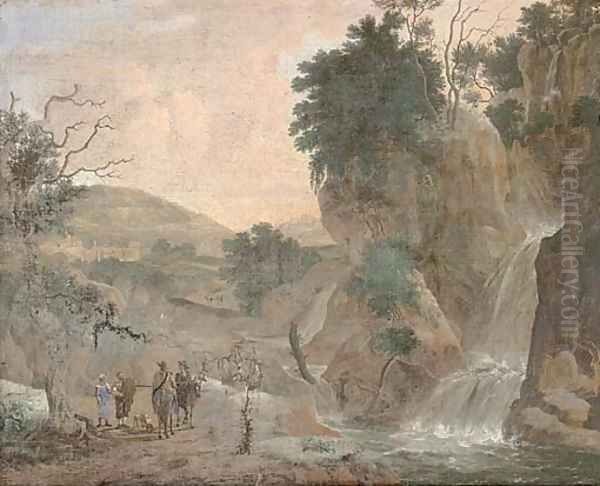

Jacob de Heusch's mature artistic style is firmly rooted in the Italianate landscape tradition. His paintings typically present idealized, rather than topographically exact, views of the Italian countryside. These are carefully composed scenes designed to evoke a sense of pastoral tranquility, classical grandeur, or sometimes the picturesque wildness associated with certain Italian landscapes.

A key characteristic is the depiction of warm, often golden, southern light. This suffuses his scenes, creating long shadows and highlighting textures, contributing significantly to the atmosphere. His handling of light and shadow demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of how illumination can define form and mood, a skill likely honed through direct observation in Italy but employed in the service of an idealized vision.

Classical ruins frequently feature in his compositions – crumbling temples, ancient bridges, tombs, or aqueducts. These elements serve not just as picturesque details but also evoke the grandeur of antiquity and the passage of time, themes popular in landscape painting of the era. They add a layer of historical resonance and often provide strong structural elements within the composition.

His landscapes are often populated with small figures – shepherds, travellers, peasants – which add scale and narrative interest but remain subordinate to the overall landscape. The natural elements – trees with detailed foliage, distant mountains often hazy in the atmospheric perspective, tranquil rivers or lakes reflecting the sky – are rendered with care, demonstrating his Dutch training in observation, yet integrated into a harmonious, idealized whole. He is also noted to have produced studies of figures and classical architecture, indicating a broader range of interests that supported his landscape work.

Influences: Dughet and Rosa

Art historians consistently point to the influence of two major figures associated with Roman landscape painting on Jacob de Heusch: Gaspard Dughet and Salvator Rosa. Both were highly influential masters whose works profoundly shaped the course of landscape painting in the 17th century.

Gaspard Dughet (also known as Gaspard Poussin, though only related to Nicolas Poussin by marriage), was renowned for his classical, orderly landscapes depicting the Roman Campagna. His works emphasize harmony, structure, and a certain serene grandeur, often featuring well-composed arrangements of trees, hills, and classical elements under a clear or gently clouded sky. De Heusch's tendency towards balanced compositions and idealized pastoral scenes likely owes a debt to Dughet's example.

Salvator Rosa, on the other hand, represented a different facet of Italian landscape. His paintings often depicted wilder, more rugged scenes – rocky gorges, stormy seas, landscapes populated by bandits or hermits. Rosa's work possessed a proto-Romantic sensibility, emphasizing the sublime and untamed aspects of nature. While de Heusch's overall style leans more towards the idyllic, the influence of Rosa might be seen in certain atmospheric effects or perhaps in the rendering of more dramatic natural features when they appear. The provided text explicitly mentions de Heusch painting "in the style of Salvator Rosa" during his travels, suggesting a direct engagement with this more dramatic mode.

De Heusch synthesized these influences, along with his Dutch background, to create his own distinct variation within the Italianate genre. His work often strikes a balance between Dughet's classicism and a gentler, more picturesque sensibility, less wild than Rosa's typical output but deeply imbued with the atmosphere of the Italian landscape as interpreted by these masters.

Representative Works

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné might be extensive, the provided information highlights specific works or types of work representative of Jacob de Heusch's oeuvre.

One key example mentioned is Arcadian Landscape. The title itself points directly to the idealized, pastoral themes central to his work. Arcadia, the mythical region of ancient Greece symbolizing rural bliss and harmony with nature, was a popular concept in Renaissance and Baroque art and literature. A painting with this title would likely feature gentle hills, shepherds, perhaps classical ruins, all bathed in the characteristic warm light, embodying the peaceful, timeless quality sought after in Italianate landscapes. It showcases his ability to create evocative, atmospheric scenes inspired by the Roman countryside and classical ideals.

Another mentioned work is Italianate river landscape. This title is more descriptive but equally indicative of his primary subject matter. Such a painting would likely feature a meandering river as a central compositional element, reflecting the sky and surrounding scenery. Banks lined with trees, perhaps a bridge (possibly ancient), distant hills, and small figures animating the scene would be typical components. This type of composition allowed de Heusch to explore effects of light on water and create depth through receding planes, common strategies in landscape painting.

The mention of a painting depicting a lake and classical ruins, estimated at auction, further reinforces the recurring themes in his work. Lakes, like rivers, offer opportunities for reflections and expansive views, while classical ruins provide historical context and visual interest. The combination is quintessentially Italianate and aligns perfectly with de Heusch's known style and subject matter. These examples collectively illustrate his focus on idealized Italian scenery, blending natural beauty with classical elements under a warm Mediterranean light.

Later Career and Artistic Output

After his formative years in Italy, Jacob de Heusch eventually returned to the Netherlands, likely settling back in Utrecht. He continued his artistic practice, drawing upon the sketches, experiences, and stylistic direction acquired during his time abroad. It is noted that he often worked up his finished paintings in the studio based on drawings made from nature, a common practice for landscape painters of the era, allowing for careful composition and idealization.

An interesting biographical detail mentioned is that he lived with a postmaster. While seemingly a minor point, it offers a glimpse into his life outside the studio, suggesting perhaps a stable domestic arrangement or a connection outside the immediate artistic circles upon his return.

Despite his evident skill and the appeal of his Italianate scenes, his overall production is not considered particularly large. Furthermore, a significant portion of his finished works were apparently destined for the Italian market, sent back to patrons or collectors in places like Rome and Venice where he had established connections. This might explain why his presence in Dutch collections, while existent, might be less prominent compared to artists who catered primarily to the domestic market. His works were appreciated by collectors who valued the Italianate style.

Legacy and Art Historical Position

Jacob de Heusch occupies a significant, if sometimes understated, position in Dutch art history. He is recognized as an important exponent of the Italianate landscape style during the later phase of the Dutch Golden Age. His work exemplifies the enduring appeal of Italy for Northern artists and demonstrates how Dutch technical skill could be adapted to render the light, atmosphere, and motifs of the Mediterranean.

He is considered influential, impacting subsequent generations of artists. The provided text specifically names Jan Frans van Bloemen (known as Orizzonte) and Andrea Locatelli as artists who felt his influence. Both were highly successful landscape painters active in Rome in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, continuing the tradition of idealized Italian landscapes. The mention of a possible influence on the younger Carlevaris, a pioneer of Venetian veduta painting, suggests his work was noted even beyond the immediate circle of landscape specialists.

However, his reputation is sometimes viewed in relation to the towering figures who influenced him. Some art historical assessments suggest that while highly competent and aesthetically pleasing, his work did not achieve the same level of originality or power as that of Gaspard Dughet or Salvator Rosa, occasionally being seen more as a skillful follower than a radical innovator.

His relatively limited output and the fact that many works went abroad may have also contributed to his being somewhat less famous than other Dutch Italianate painters like Jan Both or Nicolaes Berchem from a slightly earlier generation. Nonetheless, his paintings remain valued on the art market, appreciated for their atmospheric beauty, technical refinement, and characteristic blend of Dutch precision and Italianate idealism. He serves as a key case study for understanding the cross-cultural artistic exchanges between the Netherlands and Italy in the 17th century. The relative scarcity of detailed scholarly research specifically focused on him, as hinted in the source material, might also play a role in his current art historical standing, perhaps leaving room for future reassessment.

Conclusion

Jacob de Heusch was a talented Dutch painter whose artistic identity was forged in the crucible of Utrecht training and Roman inspiration. As the nephew and pupil of Willem de Heusch, he inherited a tradition of landscape painting, but it was his journey to Italy that truly defined his path. Immersed in the light, ruins, and artistic milieu of Rome, and engaging with the legacy of masters like Dughet and Rosa, he developed a distinctive Italianate style characterized by idealized beauty, warm atmospheres, and classical motifs.

Though perhaps not as prolific or revolutionary as some of his predecessors or contemporaries, de Heusch created a body of work admired for its refinement and evocative power. His membership in the Bentvueghels placed him within the vibrant community of Northern artists in Rome, and his influence extended to later painters like Jan Frans van Bloemen and Andrea Locatelli. His paintings, often depicting Arcadian scenes or tranquil river landscapes, continue to be appreciated as fine examples of the enduring dialogue between Dutch art and the allure of the Italian landscape during the Baroque era. He remains an important figure for understanding the international currents that enriched Dutch Golden Age painting.