Cornelis van Poelenburch stands as a seminal figure in the rich tapestry of the Dutch Golden Age of painting. Active during the 17th century, a period of extraordinary artistic flourishing in the Netherlands, Poelenburch carved a distinct niche for himself. He is celebrated primarily as a landscape painter and is recognized as one of the founding fathers of the Dutch Italianate style – a movement characterized by artists who travelled to Italy and returned to infuse their native Dutch traditions with the light, ruins, and classical spirit of the South. Born around 1594 or 1595 in Utrecht and passing away in the same city in 1667, his long career witnessed significant shifts in artistic taste, yet his finely wrought, luminous landscapes maintained considerable appeal.

Poelenburch's works, typically small in scale and often executed on copper or panel, possess a jewel-like quality. They frequently depict idyllic landscapes inspired by the Roman Campagna, populated with small figures enacting biblical narratives, mythological tales, or pastoral scenes. His mastery in rendering the soft, warm light of Italy, combined with meticulous detail and a smooth, polished finish, earned him widespread acclaim during his lifetime and secured his place in art history. He was not merely an imitator of Italian styles but a skillful synthesizer, blending the atmospheric perspective and classical motifs of the South with the Northern European tradition of detailed observation.

Early Life and Training in Utrecht

Cornelis van Poelenburch hailed from a respectable family in Utrecht, a city that was a vibrant artistic centre in the Netherlands, particularly known for its unique blend of native and international influences, including the impact of Caravaggism. His father, Simon van Poelenburch, held the position of a canon at the prominent Utrecht Cathedral, indicating a certain social standing. Unfortunately, his father passed away in 1596, when Cornelis was just an infant. His mother, Adriana van der Willigen, also came from a notable family background. This upbringing likely provided him with a solid foundation, though details of his earliest education remain scarce.

Around 1610, the young Poelenburch embarked on his formal artistic training, entering the studio of Abraham Bloemaert. Bloemaert was a highly respected and versatile painter in Utrecht, known for his Mannerist and later classicizing styles, and a teacher to many significant artists of the next generation, including Gerard van Honthorst and Hendrick ter Brugghen. Studying under Bloemaert would have exposed Poelenburch to a range of subjects and techniques, providing him with essential skills in drawing, composition, and painting. Bloemaert's own adaptability and engagement with different artistic currents may have encouraged Poelenburch's later openness to Italian influences.

Beyond Bloemaert's direct tutelage, Poelenburch's early development seems to have been touched by the work of artists sometimes referred to as the "Pre-Rembrandtists," particularly the Pynas brothers, Jan and Jacob, based in Amsterdam. These artists were known for their small-scale history paintings often set within landscapes, characterized by strong light effects and dramatic storytelling, elements that perhaps resonated with Poelenburch's burgeoning interest in narrative landscape. This early exposure set the stage for his pivotal journey south.

The Transformative Years in Italy

Like many ambitious Northern European artists of his time, Poelenburch felt the magnetic pull of Italy, the cradle of classical antiquity and the Renaissance. Around 1617, he embarked on the journey to Rome, the ultimate destination for artists seeking to study the masterpieces of the past and absorb the unique atmosphere and light of the Italian peninsula. He would remain in Italy for a significant period, likely until 1625 or 1626, and these years proved profoundly formative for his artistic vision.

In Rome, Poelenburch immersed himself in the city's artistic milieu. He undoubtedly studied the works of Renaissance masters like Raphael, whose idealized figures and harmonious compositions left an imprint on his own figure painting. However, the most decisive contemporary influences came from artists who were themselves foreigners working in Rome, particularly the German painter Adam Elsheimer and the Flemish painter Paul Bril. Elsheimer, though he died relatively young in 1610, left a powerful legacy with his small, intensely atmospheric paintings, often on copper, known for their innovative handling of light and poetic mood. Poelenburch clearly absorbed Elsheimer's sensitivity to light effects and his preference for the small, cabinet-sized format.

Paul Bril, an established and successful landscape painter who had been working in Rome for decades, offered another crucial model. Bril's landscapes, evolving from a late Mannerist style towards a more naturalistic and classical approach, provided Poelenburch with examples of how to structure idealized Italianate views, often incorporating ancient ruins. Poelenburch is known to have had close contact with Bril, and the influence is evident in the compositional strategies and motifs found in Poelenburch's Italian-period works. Some art historians even suggest a possible collaborative relationship between Bril and Elsheimer, which could have further facilitated the transmission of ideas to the younger Dutch artist.

During his Roman sojourn, Poelenburch became a founding member of the Bentvueghels ("Birds of a Feather"), a society of mostly Dutch and Flemish artists living in Rome. Known for their bohemian lifestyle and initiation rituals, the Bentvueghels provided a network of camaraderie and professional support. Members adopted nicknames, or "bent" names; Poelenburch was known as 'Satiro' (Satyr), a moniker that perhaps alluded to the mythological figures often populating his idyllic landscapes or maybe hinted at a playful aspect of his personality or art. Other notable members included painters like Bartholomeus Breenbergh, who became a close contemporary and sometimes competitor in the Italianate landscape genre, and Herman van Swanevelt.

Poelenburch's talent did not go unnoticed by Italian patrons. He gained the favour of the Grand Duke Cosimo II de' Medici in Florence, a significant mark of recognition. This patronage suggests his works, which skillfully blended Northern finesse with Italianate themes and settings, found favour within elite circles. While in Italy, he also established contact with the innovative French engraver Jacques Callot, indicating his integration into a broader international artistic community.

Development of a Unique Style

The years spent in Italy cemented Cornelis van Poelenburch's artistic identity. He returned to Utrecht not merely as a painter who had seen Italy, but as a leading exponent of a new sensibility – the Dutch Italianate landscape. His signature style, refined throughout his career but established during and shortly after his Italian stay, is marked by several key characteristics that distinguish his work.

Foremost is his preference for small-format paintings, often executed on wood panel or, notably, on copper. The smooth, non-absorbent surface of copper allowed for an exceptionally fine finish, enhancing the enamel-like quality and luminosity of his works. This choice of support complemented his meticulous technique and the intimate scale of his scenes, making them desirable collector's items, often referred to as cabinet pieces.

His subject matter typically revolved around idealized landscapes inspired by the Roman Campagna – the countryside surrounding Rome, known for its rolling hills, classical ruins, and distinctive light. These landscapes, however, were rarely topographically exact representations. Instead, Poelenburch composed arcadian visions, often bathed in a soft, golden, or silvery light that evoked a timeless, poetic atmosphere. He became particularly renowned for capturing the specific quality of Italian light, a warm, hazy glow that unified his compositions and softened contours.

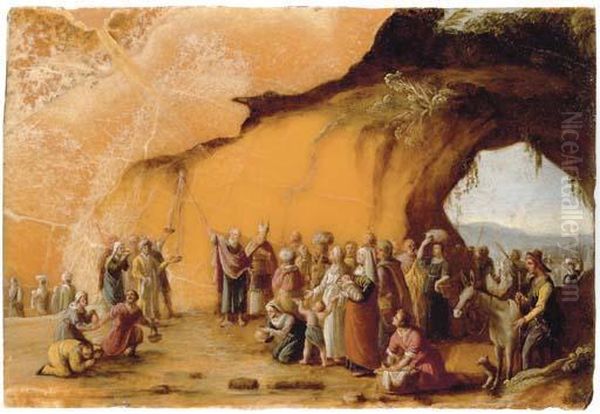

Within these luminous settings, Poelenburch integrated small figures, often drawn from biblical stories (like the Flight into Egypt or scenes from the Old Testament, such as Moses Striking the Rock), classical mythology (nymphs, satyrs, gods, and goddesses, as seen in Apollo and Callisto), or pastoral life. His figures, frequently depicted nude or semi-nude, are typically rendered with smooth, porcelain-like skin and idealized forms, recalling the influence of Renaissance masters like Raphael, albeit translated into a much smaller scale. The inclusion of recognizable ancient ruins – crumbling temples, aqueducts, or sculptures – became a hallmark of his work, adding a layer of historical resonance and melancholy charm.

Poelenburch achieved a unique synthesis. He combined the detailed observation and refined technique characteristic of the Northern European tradition, particularly evident in the rendering of foliage and textures, with the grander compositional schemes, idealized forms, and atmospheric light associated with Italian art. Unlike the more naturalistic Dutch landscape painters who focused on their native scenery, Poelenburch offered escapist visions of a sun-drenched, classical past. His polished surfaces and harmonious compositions stood in contrast to the more dramatic chiaroscuro effects found in the works of the Utrecht Caravaggisti like Honthorst or Ter Brugghen, though he shared their context in Utrecht's diverse art scene.

Return to Utrecht and Established Career

Upon his return to Utrecht around 1626, Cornelis van Poelenburch quickly established himself as one of the city's most sought-after artists. His Italian experiences, combined with his innate talent and refined technique, set him apart. He rejoined the Utrecht painters' Guild of St. Luke, becoming its dean in later years (1649, 1655-1656, 1658-1659), a sign of the high esteem in which his colleagues held him. His Italianate landscapes, with their appealing blend of classical themes, idyllic scenery, and exquisite execution, found a ready market among discerning collectors both in Utrecht and beyond.

His studio became highly productive, and his style, once established, remained relatively consistent throughout his long career, attesting to its enduring popularity. He specialized in these small, highly finished cabinet pieces, which were perfectly suited for the intimate contemplation and display in the homes of wealthy burghers and aristocrats. The demand for his work was such that he became one of the most successful and financially comfortable artists in Utrecht.

His paintings were praised for their elegance, their delicate rendering of light, and their ability to transport the viewer to a serene, arcadian world. While he occasionally painted larger works, his reputation rested firmly on these smaller, jewel-like creations. His success demonstrates the growing taste in the Netherlands for art that looked beyond native borders, embracing the classical ideals and sunny climes of Italy, even as the more 'native' Dutch landscape tradition also flourished. Poelenburch effectively catered to a sophisticated clientele eager for works that spoke of culture, refinement, and a connection to the classical past.

Royal Patronage in England

The renown of Cornelis van Poelenburch extended well beyond the borders of the Dutch Republic. His reputation reached the ears of one of the most significant art collectors and patrons of the era, King Charles I of England. Charles I, known for his sophisticated taste and his efforts to build a magnificent royal collection, actively sought out leading artists from across Europe. Around 1637 or 1638, Poelenburch received an invitation to travel to London and work for the English court.

He accepted the invitation and spent approximately four years in England, from about 1638 to 1641 or 1642. During this period, he worked alongside other prestigious court artists, contributing to the vibrant artistic environment fostered by Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria. His specific role involved creating paintings, particularly the small-scale cabinet pieces for which he was famous, likely intended for the King's private apartments or collections. The reference to him making "small furniture" in some sources likely misinterprets his creation of these precious paintings designed for intimate viewing or integration into elaborate cabinets.

This period of royal service in England represents a significant peak in Poelenburch's career, underscoring his international standing. Working for Charles I placed him in the company of artists like Anthony van Dyck, who was the principal court painter at the time. While Poelenburch's stay was relatively brief, cut short perhaps by the looming political turmoil that would lead to the English Civil War, it confirmed his status as an artist of European significance. His elegant, classicizing style would have resonated well with the tastes of the Stuart court, which favoured refinement and continental sophistication.

Collaborations and Workshop

Cornelis van Poelenburch was not only a successful independent artist but also engaged in collaborations and maintained an active workshop. Collaboration was a common practice in the 17th-century Netherlands, allowing artists to leverage their respective specializations. Poelenburch, renowned for his skillfully rendered figures, sometimes painted the staffage (figures) into landscapes created by other artists. Conversely, other landscape or architectural specialists might provide the settings for his figures.

One of his known collaborators was Alexander Keirincx, a Flemish landscape painter who also spent time in Utrecht and later worked in England for Charles I around the same time as Poelenburch. Their combined skills would have resulted in works blending Keirincx's detailed rendering of trees and scenery with Poelenburch's characteristic mythological or biblical figures. He is also documented as having collaborated with Bartholomeus Breenbergh, his fellow Bentvueghels member and friendly rival in the Italianate genre. Though their styles are distinct, with Breenbergh often favouring more dramatic ruins and light, collaborations or mutual influence certainly occurred. Jan Both, another leading Utrecht Italianate painter, may also have interacted professionally with Poelenburch, as they moved in the same artistic circles.

Poelenburch also ran a successful workshop, training a number of pupils who went on to become painters in their own right, often working in a style heavily indebted to their master. Among his documented students are Daniel Vertangen, François Verwilt, Johan van Haensbergen, Dirck van der Lisse, and Warnard van Rysen. Abraham van Cuylenborch is another artist whose style is deeply influenced by Poelenburch, suggesting he may also have been a pupil or close follower. These students helped to disseminate Poelenburch's popular Italianate style, ensuring its continuation into the next generation of Dutch painters. His role as a teacher further cemented his importance within the Utrecht art scene.

Representative Works

Cornelis van Poelenburch's extensive oeuvre consists primarily of small-scale landscapes with mythological or biblical themes. Several works stand out as representative of his style and preoccupations.

The Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence: This subject, depicting the gruesome death of the early Christian martyr roasted on a gridiron, might seem unusual for an artist known for idyllic scenes. However, it allowed Poelenburch to combine a historical narrative with a complex figural composition, often set against a backdrop featuring Roman architecture, showcasing his ability to handle dramatic themes within his refined style.

Apollo and Callisto: Mythological subjects featuring gods, goddesses, nymphs, and satyrs were a staple of Poelenburch's output. Scenes like Apollo and Callisto, or numerous depictions of Nymphs Bathing, Diana and her Nymphs, or Bacchanals, allowed him to explore the idealized nude figure within his characteristic luminous, arcadian landscapes. These works epitomize the escapist, classical fantasy that appealed so strongly to his patrons.

Moses Striking the Rock (or similar Old Testament scenes): Biblical narratives set in landscape settings were also common. Works depicting Moses, or the Flight into Egypt, allowed Poelenburch to integrate religious storytelling with his Italianate scenery. The figures, though small, convey the narrative effectively within the expansive, light-filled environment.

Landscape with Roman Ruins: Many of Poelenburch's paintings feature identifiable or imaginary Roman ruins as prominent elements. These works, sometimes with minimal staffage, highlight his fascination with classical antiquity and his skill in rendering architecture bathed in atmospheric light. They evoke a sense of nostalgia and the passage of time, key themes within the Italianate tradition.

These examples illustrate the core elements of Poelenburch's art: the small format, often on copper or panel; the smooth, detailed finish; the Italianate landscape setting inspired by the Campagna; the masterful handling of soft, warm light; the inclusion of small, idealized figures (often nude) drawn from mythology or the Bible; and the frequent incorporation of classical ruins. His works consistently project an air of serenity, elegance, and timeless beauty.

Influence and Legacy

Cornelis van Poelenburch's impact on Dutch art was significant, particularly through his role as a pioneer of the Italianate landscape style. He was among the first generation of Dutch artists, along with contemporaries like Breenbergh, who successfully translated their experiences of Italy into a distinctively Dutch mode of painting that proved immensely popular and influential.

His success spawned numerous followers and imitators in Utrecht and beyond. Artists like Dirck van der Lisse, Daniel Vertangen, and Johan van Haensbergen directly continued his style, often making it difficult to distinguish their works from the master's. The broader Italianate movement flourished in the Netherlands throughout the mid-17th century, with artists like Jan Both, Nicolaes Berchem, Karel Dujardin, and Adam Pynacker developing the genre further, often working on larger canvases and incorporating more elements of daily life, but still indebted to the foundations laid by Poelenburch and Breenbergh.

The relationship between Poelenburch and the slightly younger, highly influential French landscape painter Claude Lorrain, who also worked in Rome, is complex and debated by scholars. While both artists shared an interest in idealized landscapes bathed in poetic light, the precise direction of influence is unclear. They certainly knew each other's work, and it's likely there was mutual influence. Poelenburch's established success with luminous, small-scale Italianate scenes may have contributed to the artistic environment in which Claude developed his own grander, more atmospheric visions.

Poelenburch's paintings were highly prized by collectors throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, both in the Netherlands and internationally. His works entered prestigious collections, including royal inventories like that of Charles I, and were sought after by wealthy merchants and aristocrats. Today, his paintings are held by major museums worldwide, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Mauritshuis in The Hague, the Louvre in Paris, the National Gallery in London, the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, and the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, attesting to his enduring appeal and historical importance.

Later Life and Conclusion

After his return from England in the early 1640s, Cornelis van Poelenburch settled back into his successful career in Utrecht. He remained active as a painter and a prominent figure in the city's artistic community for over two more decades. He continued to produce his popular Italianate landscapes, maintaining the high quality and refined style that had brought him fame. His continued activity is evidenced by his repeated service as dean of the painters' guild during the 1650s.

He passed away in Utrecht on August 12, 1667, at the age of approximately 72 or 73. He left behind a substantial body of work and a significant artistic legacy. As a founder of the Dutch Italianate landscape tradition, he played a crucial role in broadening the scope of Dutch art, introducing a classical, sunlit alternative to the more prevalent naturalistic depictions of the local environment.

Cornelis van Poelenburch's art represents a masterful fusion of Northern European precision and Italian classical idealism. His small, jewel-like paintings, celebrated for their exquisite detail, harmonious compositions, and above all, their magical rendering of light, captivated audiences in his own time and continue to enchant viewers today. He remains a key figure for understanding the international connections and diverse currents within the remarkable artistic phenomenon that was the Dutch Golden Age.