Jan Sanders van Hemessen stands as a pivotal figure in the vibrant artistic landscape of sixteenth-century Antwerp. A leading exponent of Northern Mannerism, his work forms a fascinating bridge between the established traditions of Flemish painting and the powerful innovations arriving from Renaissance Italy. Active during a period of immense economic growth and cultural exchange, Hemessen carved a distinct niche for himself with his dynamic compositions, robust figures, and a keen interest in depicting human character, often focusing on themes of morality, faith, and folly. His legacy is complex, marked by powerful religious narratives, engaging genre scenes, and a workshop that included his talented daughter, Catharina, yet also touched by questions of attribution and influence that continue to engage art historians.

Origins and Early Influences

Born around 1500 in Hemiksem, a village near Antwerp, Jan Sanders adopted the name "van Hemessen" from his place of birth, a common practice at the time. Details surrounding his artistic training remain elusive, as no definitive records name his master. However, given his emergence in Antwerp, the dominant artistic centre of the Low Countries, it is highly probable that he apprenticed within the city's thriving artistic milieu. Some scholars speculate about a connection to the workshop of Hendrick van Cleve I, though this remains unproven. The prevailing style in Antwerp during his formative years was shaped by masters like Quentin Matsys, whose work blended late Gothic sensibilities with emerging Renaissance ideals, providing a rich local context.

A crucial element in Hemessen's development was almost certainly a journey to Italy, likely undertaken in the 1520s. While direct documentation is lacking, the profound impact of Italian art, particularly the High Renaissance and burgeoning Mannerist styles, is undeniable in his mature work. The monumentality, anatomical confidence, and dynamic posing seen in the works of Michelangelo and Raphael, as well as contemporary Mannerists, clearly resonated with Hemessen. He absorbed these influences not merely as a copyist, but integrated them into a distinctly Northern European framework, retaining a Flemish penchant for detailed realism and expressive characterisation.

Antwerp: Career and Guild Activities

By 1524, Jan Sanders van Hemessen was established enough to be registered as a master in the prestigious Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke. This membership marked his official entry into the city's professional artistic community, granting him the right to establish his own workshop, take on apprentices, and sell his works. Antwerp, at this time, was one of Europe's wealthiest port cities, a hub of international trade and finance, which fostered a demanding and diverse art market. Patrons included wealthy merchants, the church, civic institutions, and foreign traders, creating opportunities for artists working in various genres.

Hemessen quickly gained prominence within the Guild. His skill and reputation grew, leading to his election as Dean (deken) of the Guild for the year 1547-1548. This position was one of considerable honour and responsibility, involving the administration of the Guild's affairs, upholding its standards, and representing its interests. Holding this office indicates the high esteem in which Hemessen was held by his peers. His workshop flourished, producing a significant body of work that catered to the varied tastes of the Antwerp market, ranging from large-scale religious altarpieces to smaller, more intimate genre scenes and portraits.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of North and South

Hemessen's style is best characterized as Northern Mannerism, a movement that adapted the sophisticated, often artificial elegance and dynamism of Italian Mannerism to a Northern European context. He embraced the Mannerist tendency towards elongated figures, complex and sometimes contorted poses, and crowded, energetic compositions. His figures often possess a muscular, sculptural quality, recalling the heroic nudes of Michelangelo, yet they are rendered with a Flemish attention to texture, detail, and individual physiognomy.

Unlike some Italian Mannerists who prioritized grace and artifice (like Bronzino or Parmigianino), Hemessen often infused his scenes with a raw energy and earthiness. His figures can be robust, even coarse, particularly in his genre scenes. He employed strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to heighten drama and model form, creating a sense of tangible volume. His colour palettes could be bold and sometimes dissonant, contributing to the emotional intensity of his works. This unique blend resulted in paintings that were both stylistically sophisticated, referencing the admired Italian models, and deeply rooted in the expressive realism characteristic of Netherlandish art, seen earlier in artists like Hieronymus Bosch and later perfected by Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

Themes and Subject Matter: Faith, Folly, and Humanity

Hemessen's oeuvre encompasses a range of subjects, but he showed a particular affinity for religious narratives and moralizing genre scenes, often blurring the lines between the two.

Religious Paintings

Hemessen produced numerous works depicting biblical episodes, often choosing moments of high drama or profound spiritual significance. His Calling of Saint Matthew (c. 1536), for example, transforms the biblical event into a bustling scene filled with vividly characterized figures, contrasting the worldly concerns of the tax collectors with the quiet authority of Christ's call. The detailed depiction of coins, ledgers, and contemporary attire grounds the sacred story in a familiar, tangible reality.

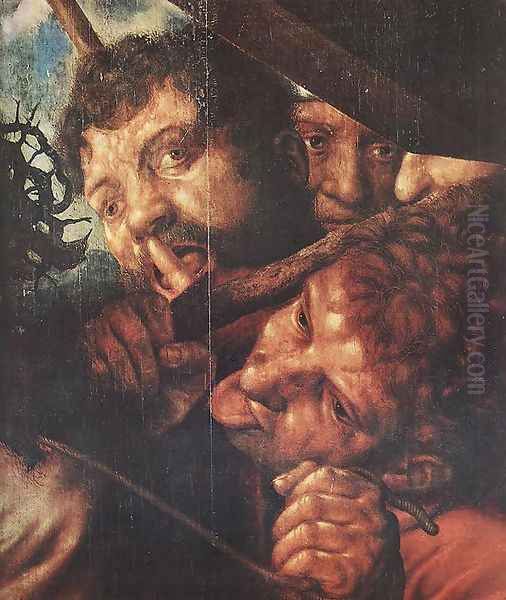

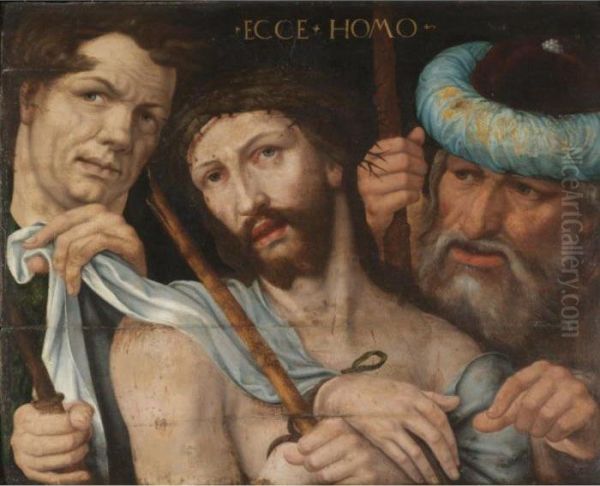

Other significant religious works include Christ Carrying the Cross, Ecce Homo, Isaac Blessing Jacob, and Judith with the Head of Holofernes. In these paintings, Hemessen often employed Mannerist devices – dynamic diagonals, foreshortening, and expressive gestures – to convey the emotional weight of the narrative. His depiction of Saint Jerome (several versions exist) showcases his ability to render powerful, aged figures engaged in scholarly or penitential devotion, often set against detailed landscapes or studies, a theme popularised by earlier artists like Albrecht Dürer and Joachim Patinir. These works demonstrate his engagement with traditional iconography while infusing it with his characteristic vigour and psychological insight.

Moralizing Genre Scenes

Perhaps Hemessen's most distinctive contribution lies in his development of the moralizing genre scene. These paintings often depict taverns, brothels, or other settings associated with worldly temptation, serving as cautionary tales against vice. His multiple versions of The Parable of the Prodigal Son (e.g., c. 1536) are prime examples. Set within lively, contemporary tavern interiors, they vividly portray the son squandering his inheritance on wine, women, and gambling, before his eventual repentance. These scenes allowed Hemessen to explore human behaviour with unflinching realism, capturing expressions of lust, drunkenness, and greed.

Another key work in this vein is The Surgeon or The Cure of Folly (c. 1550-1555). This satirical painting depicts a charlatan surgeon pretending to remove the "stone of madness" from a patient's head, a popular allegory for human gullibility and the folly of seeking easy cures for complex problems. The grotesque expressions and the chaotic energy of the scene are characteristic of Hemessen's approach to social commentary. These works often carry inscriptions or symbolic details reinforcing their moral message, aligning Hemessen with a Northern tradition of didactic art, but presented with a new level of realism and compositional energy influenced by his Italian experiences. He shares this interest in depicting everyday life infused with moral undertones with contemporaries like Marinus van Reymerswaele, known for his portrayals of tax collectors and money changers, and anticipates the peasant scenes of Pieter Aertsen and Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

Portraits

While less numerous than his religious or genre works, Hemessen also produced portraits. These works, like his Portrait of a Man, demonstrate his skill in capturing individual likeness and character, rendered with the same robust modelling and attention to detail seen in his narrative paintings. Portraiture was a staple of the Antwerp market, and Hemessen's contributions, though perhaps overshadowed by specialists like Anthonis Mor (Antonio Moro), form part of his overall production.

Analysis of Key Works

A closer look at some of Hemessen's most celebrated paintings reveals the nuances of his style and thematic concerns.

The Surgeon (The Cure of Folly)

Held in the Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, this painting is a powerful example of Hemessen's satirical genre work. The central action involves a quack surgeon, whose intense, almost manic expression suggests his fraudulent nature, performing a mock operation. The patient, a picture of foolish trust, grimaces in pain or anticipation. Surrounding figures react with a mixture of curiosity, concern, and perhaps complicity. The composition is tight and energetic, focusing attention on the central group. Hemessen uses strong lighting to highlight the faces and hands, emphasizing the drama and the psychological interplay. The theme of removing the "stone of folly" was a popular subject in Northern European art and literature, symbolizing the critique of human stupidity and the prevalence of charlatanism. Hemessen's version is particularly forceful and unflinching in its depiction.

The Prodigal Son

The version in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels, exemplifies Hemessen's approach to this parable. The scene is set in a boisterous tavern or brothel. The Prodigal Son is shown carousing, surrounded by seductive women and dissolute companions, clearly wasting his inheritance. Hemessen fills the canvas with dynamic figures in elaborate contemporary dress, capturing the chaotic atmosphere of revelry and excess. The composition uses strong diagonals and overlapping figures to create a sense of depth and movement. In the background, often through a window or doorway, the viewer might glimpse the prodigal's eventual fate – tending pigs – or his return home, providing the moral counterpoint to the foreground's depiction of sin. The painting functions both as a lively genre scene and a clear moral warning, typical of Hemessen's didactic approach.

The Calling of Saint Matthew

Housed in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich, this work showcases Hemessen's ability to blend religious narrative with detailed genre elements. Matthew, the tax collector, is seated at a table laden with coins, surrounded by assistants and clients engaged in financial transactions. Christ, accompanied by Peter, enters from the left, his gesture commanding Matthew's attention. Hemessen masterfully contrasts the cluttered, materialistic world of the tax collectors with the spiritual gravity of Christ's call. The figures are robust and individualized, their expressions ranging from surprise and avarice to contemplation. The detailed rendering of clothing, coins, and the office setting demonstrates Hemessen's Flemish heritage, while the powerful figure types and dynamic composition reflect his assimilation of Italian Renaissance ideals. The work serves as a commentary on wealth, vocation, and the transformative power of faith.

Workshop, Students, and Collaborations

Like most successful masters of his time, Jan Sanders van Hemessen operated a busy workshop to meet the demand for his paintings. He would have employed assistants and apprentices who helped with preparing panels, grinding pigments, painting backgrounds, and producing copies or variants of popular compositions. This workshop practice accounts for the variations seen in some of his repeated subjects, like The Prodigal Son or Saint Jerome.

His most notable pupil was undoubtedly his own daughter, Catharina van Hemessen (c. 1527/28 – after 1567). Trained by her father, Catharina became a skilled painter in her own right, specializing primarily in portraits, though she also produced some religious compositions. She is significant as one of the earliest documented female Flemish painters for whom a signed body of work survives. Her style clearly shows her father's influence in its solid modelling and realistic detail, though her portraits often possess a quieter, more reserved quality. She gained international recognition, eventually working for Mary of Hungary, Regent of the Netherlands. The fact that Jan trained his daughter to a professional level was somewhat unusual for the time and speaks to a potentially progressive attitude towards female education within the family. Records indicate Catharina herself later taught three male apprentices, though their names are not preserved.

Evidence also suggests collaboration between Jan Sanders van Hemessen and other artists. Documents mention a joint project with the younger Pieter Aertsen on an altarpiece for the Church of St. James in Antwerp, where Hemessen was responsible for the main figures and Aertsen for the smaller figures and background elements. Such collaborations were common in the efficient Antwerp art market. He may also have had connections with Pieter Coecke van Aelst, another prominent Antwerp master known for his Italianate style and large workshop.

Attribution remains a challenge with Hemessen and his circle. The "Brunswick Monogrammist," an anonymous but highly skilled contemporary active in Antwerp, produced works stylistically related to Hemessen, particularly genre scenes, leading to past confusion and ongoing scholarly debate about the relationship between the two artists – some have even speculated they might be the same person, or that the Monogrammist was a close follower or workshop collaborator.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Jan Sanders van Hemessen worked during a golden age for Antwerp painting. He was part of a generation of artists grappling with the legacy of earlier Netherlandish masters while responding to the powerful influence of the Italian Renaissance. His contemporaries included:

Quentin Matsys (c. 1466–1530): A leading figure in the generation before Hemessen, Matsys helped establish Antwerp's artistic reputation, blending late Gothic refinement with Renaissance humanism and psychological depth.

Joos van Cleve (c. 1485–1540/41): Known for his devotional paintings and portraits, often incorporating Italianate motifs and Leonardesque sfumato.

Joachim Patinir (c. 1480–1524): A pioneer of landscape painting as an independent genre, whose panoramic views likely influenced the landscape backgrounds in some of Hemessen's works.

Marinus van Reymerswaele (c. 1490–c. 1546): Specialized in satirical genre scenes, particularly depictions of tax collectors and money changers, sharing Hemessen's interest in themes of greed and worldly corruption.

Pieter Coecke van Aelst (1502–1550): A prominent Romanist painter, architect, and designer of tapestries and stained glass, known for his elegant figures and elaborate compositions influenced by Italian art.

Lambert Lombard (1505–1566): A key figure in introducing Italian High Renaissance principles to Liège and the wider region, emphasizing classical learning and archaeological accuracy.

Frans Floris (c. 1519–1570): Became the leading history painter in Antwerp after Hemessen's peak, running a large, highly organized workshop and fully embracing a heroic, Italianate style.

Pieter Aertsen (1508–1575): A collaborator with Hemessen, Aertsen pioneered large-scale market and kitchen scenes, often embedding religious narratives within bustling depictions of everyday life, influencing later still life and genre painting.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525–1569): Though slightly younger, Bruegel overlapped with Hemessen's later career. While Bruegel developed a unique style focused on peasant life and landscape, he shared Hemessen's interest in moralizing themes and observing human nature.

This rich artistic environment fostered competition, collaboration, and stylistic exchange, pushing artists like Hemessen to innovate while catering to a sophisticated market.

Later Life and Legacy

Information about Hemessen's final years is less clear. Some sources suggest he may have moved from Antwerp to Haarlem, another important artistic centre in the Northern Netherlands, possibly around the mid-1550s. This move might have been related to religious reasons, as Protestant sympathies grew in the region, or simply seeking new opportunities. However, evidence for this move remains debated among scholars, with some sources mentioning The Hague instead.

The exact date of his death is also uncertain, typically placed sometime between 1556 and 1566, with c. 1566 often cited based on Guild records or interpretations thereof. Regardless of the precise date and location, by the time of his death, Jan Sanders van Hemessen had made a significant impact on Netherlandish art.

His legacy lies primarily in his role as a key transmitter and adapter of Italian Mannerist ideas into a Northern context. He helped popularize certain types of moralizing genre scenes, like The Prodigal Son and depictions of taverns or brothels, which became staples of later Flemish and Dutch painting. His robust, often earthy portrayal of human figures and his interest in psychological expression influenced subsequent generations of genre painters. His workshop practice and the success of his daughter Catharina also highlight aspects of artistic training and the potential, albeit limited, for female artists in the period. While perhaps overshadowed in popular imagination by contemporaries like Bruegel, Hemessen remains a crucial figure for understanding the complex artistic developments in Antwerp during the sixteenth century.

Art Historical Assessment and Controversies

Jan Sanders van Hemessen is recognized by art historians as a major painter of the Antwerp school during the mid-sixteenth century. His ability to synthesize Italian monumentality and dynamism with Flemish realism and detail is widely acknowledged. His contribution to the development of moralizing genre painting is considered particularly important, paving the way for later masters.

However, his reputation is not without complexities. Attribution issues persist, with ongoing debates about the precise extent of his oeuvre versus that of his workshop or close followers like the Brunswick Monogrammist. Some critics have historically viewed his style as somewhat coarse or overly reliant on Italian models, questioning his originality compared to figures like Bruegel. Nonetheless, modern scholarship generally appreciates the power and expressiveness of his work, recognizing his skill in composition, characterization, and his unique blending of diverse artistic currents. He remains a testament to the dynamism and internationalism of Antwerp's art world in the sixteenth century, an artist whose work continues to engage viewers with its energy, realism, and insightful commentary on the human condition.

Conclusion

Jan Sanders van Hemessen navigated the rich and complex artistic currents of his time with remarkable skill and individuality. Emerging from the vibrant hub of Antwerp, he absorbed the lessons of both his Netherlandish heritage and the transformative art of Renaissance Italy. The result was a powerful, distinctive style characterized by dynamic compositions, robust figures, and a keen psychological insight. Whether depicting dramatic biblical narratives or offering cautionary glimpses into the follies and vices of contemporary life, his paintings resonate with energy and moral purpose. Through his influential works, his active workshop, and the notable career of his daughter Catharina, Hemessen left an indelible mark on the course of Northern European art, solidifying his place as a key master of Antwerp Mannerism.