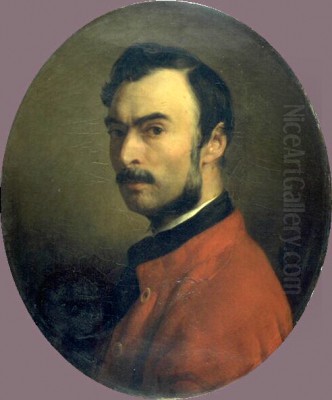

Jacques Raymond Brascassat stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French art. Renowned primarily for his meticulous and empathetic depictions of animals, particularly cattle, and his evocative landscapes, Brascassat carved a distinct niche for himself within an era of dynamic artistic change. His work, deeply rooted in academic tradition yet infused with a profound observation of nature, reflects both the enduring legacy of Neoclassicism and the burgeoning interest in Realism that characterized the period. His journey from a promising student in Bordeaux to a respected member of the French artistic establishment in Paris is a testament to his dedication, skill, and unique artistic vision.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born on August 30, 1804, in the vibrant port city of Bordeaux, Jacques Raymond Brascassat's artistic inclinations manifested early. His initial training was under the guidance of Théodore Richard, a local landscape painter who likely instilled in him a foundational appreciation for the direct study of nature. Seeking to further hone his talents, Brascassat moved to Paris, the epicenter of the French art world, to study at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. There, he entered the atelier of Louis Hersent, a respected historical and portrait painter, and also received instruction from Paul Delaroche, another prominent figure known for his historical scenes, often imbued with a dramatic, almost theatrical, realism.

This academic training was crucial in shaping Brascassat's technical proficiency. The emphasis on precise draughtsmanship, compositional harmony, and the study of Old Masters, which were hallmarks of the École des Beaux-Arts curriculum championed by figures like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, provided him with a strong artistic grounding. Even as he later specialized in animal and landscape painting, the discipline and rigor of his early education remained evident in the clarity and structure of his compositions.

The Pivotal Prix de Rome and Italian Sojourn

A significant turning point in Brascassat's early career came in 1825. He competed for the coveted Prix de Rome, a scholarship awarded by the French government that allowed promising young artists to study in Rome. While he did not win the first prize for historical landscape, his painting depicting a "Meleager Hunting" scene secured him the second prize. This achievement was substantial enough to earn him a stipend, enabling him to travel to Italy for a period of four years. This Italian sojourn, from roughly 1826 to 1830, proved to be immensely formative.

Italy, with its sun-drenched landscapes, classical ruins, and rich artistic heritage, offered a wealth of inspiration. Brascassat immersed himself in studying the Italian countryside, particularly the Roman Campagna, and the works of past masters. He was reportedly influenced by the classical landscape tradition of artists like Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin, whose idealized yet carefully observed depictions of the Italian scene had set a standard for generations. He also encountered the work of British artists in Italy, such as the linear precision of John Flaxman and the atmospheric watercolors of Francis Towne, which may have informed his approach to landscape. During these years, he produced numerous sketches and studies, meticulously documenting the natural world, ancient monuments, and the pastoral life he encountered. This period was crucial for developing his skills in rendering light, atmosphere, and the specific character of a place.

The Rise of an Animalier: Brascassat's Mastery of Animal Painting

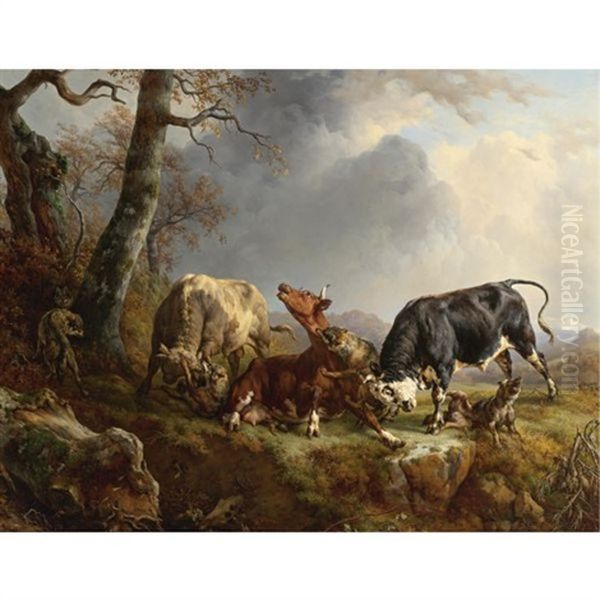

Upon his return to France, Brascassat increasingly focused on animal painting, a genre that was gaining popularity and prestige during the 19th century. He became particularly renowned for his depictions of cattle, sheep, and dogs, which he portrayed with remarkable anatomical accuracy, sensitivity, and a deep understanding of their individual character. His approach was far from sentimental; instead, he imbued his animal subjects with a sense of dignity and realism, often placing them within carefully rendered landscape settings that complemented their presence.

His success in this field was marked by several key works. The painting Bulls Fighting, exhibited in 1837, is often cited as one of his masterpieces in this genre. This dynamic composition captures the raw power and tension of the confrontation, showcasing his skill in rendering animal anatomy in motion. Another significant work, Cow Attacked by Wolves and Defended by a Bull (1845), further demonstrated his ability to create dramatic narratives centered on animal subjects. These paintings, along with others like Two Bulls, were lauded for their verisimilitude and the artist's evident empathy for his subjects. His meticulous attention to detail, from the texture of an animal's hide to the subtle nuances of its posture, set his work apart.

Brascassat's dedication to animal painting was profound. He was among the pioneering artists who purchased animals specifically to serve as models for his paintings. In 1858, with the assistance of the painter Robert Fleury, he acquired a house where he could keep his animal collection, effectively creating a private menagerie for artistic study. This practice allowed for sustained, close observation, contributing to the authenticity of his work. He also drew inspiration from public collections, such as the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, which housed a variety of exotic animals. One famous resident, a giraffe, captivated Parisian society and became the subject of numerous artistic depictions, including, it is believed, works by Brascassat, and even inspired a popular hairstyle, "à la girafe."

His focus on animal subjects placed him in the company of other notable animaliers of the era. While sculptors like Antoine-Louis Barye were bringing a new level of dynamism and anatomical precision to animal sculpture, painters like Rosa Bonheur and Constant Troyon were achieving widespread acclaim for their depictions of animals. Bonheur, in particular, was celebrated for her large-scale, powerful portrayals of horses and other livestock, while Troyon, initially a landscape painter associated with the Barbizon School, increasingly incorporated animals as central elements in his compositions, often with a similar rustic charm to Brascassat's work. Brascassat's contribution was distinct in its often more intimate scale and its specific focus on the individual character of the animals, influenced perhaps by 17th-century Dutch masters like Paulus Potter and Aelbert Cuyp.

Landscapes: A Synthesis of Tradition and Observation

While animal painting became his primary focus, Brascassat continued to produce significant landscape works throughout his career. His landscapes often reflected the influence of his Italian studies, blending a Neoclassical sense of order and composition with a more direct, realistic observation of nature. He was particularly adept at depicting trees, rendering their forms and foliage with the same meticulous care he applied to his animal subjects.

His Italian landscapes, such as Peasant and his Herd in the Roman Countryside, capture the distinctive light and atmosphere of the region, often featuring pastoral scenes with shepherds and their flocks, or views of ancient ruins integrated into the living landscape. These works show an affinity with the historical landscape tradition of Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes, who advocated for outdoor sketching as a means to capture natural effects.

Back in France, his landscapes continued to evolve. While not directly part of the Barbizon School – a group of painters including Théodore Rousseau, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Charles-François Daubigny, and Jules Dupré, who championed painting en plein air and a more naturalistic depiction of the French countryside – Brascassat shared their commitment to careful observation. However, his style generally remained more polished and detailed than the often broader, more atmospheric approach of many Barbizon painters. His work retained a connection to the Dutch Golden Age landscape tradition, particularly artists like Jacob van Ruisdael or Meindert Hobbema, in its detailed rendering of foliage and its appreciation for the rustic charm of the countryside.

Academic Recognition and Professional Success

Brascassat's dedication and talent did not go unnoticed by the French artistic establishment. He regularly exhibited at the Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, which was the primary venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage. His works were generally well-received, earning him medals and critical acclaim. His success culminated in his election as a member of the prestigious French Academy of Sciences (Académie des Beaux-Arts, Institut de France) in 1846, a significant honor that solidified his standing in the art world.

He also cultivated important relationships with patrons and collectors. A notable friendship developed in the 1850s with Hugues Krafft, a discerning businessman and art enthusiast. Krafft became a significant collector of Brascassat's works, and upon his death, this collection was generously bequeathed to the Musée de Tessé in Le Mans, where it forms an important part of the museum's holdings of 19th-century art. This patronage was crucial for Brascassat, providing financial stability and ensuring the preservation of his artistic legacy.

Despite his professional successes, Brascassat's later years were marked by declining health. However, he continued to paint, and his reputation as a leading animal and landscape painter remained secure. His art, with its blend of academic rigor and keen observation, appealed to a broad audience that appreciated both technical skill and a faithful representation of the natural world.

Personal Glimpses and Character

While detailed accounts of Brascassat's personal life are not abundant, some anecdotes offer glimpses into his character and working methods. His commitment to keeping animals for study underscores his dedication to authenticity. The story of the Parisian giraffe inspiring art and fashion highlights the cultural milieu in which he operated, where zoological curiosities could capture the public imagination and intersect with artistic trends.

Some more esoteric accounts, possibly drawing from contemporary perceptions or later astrological interpretations, have described Brascassat as possessing traits such as intelligence, elegance, and a well-organized mind, coupled with passion and vitality. While such descriptions fall outside conventional art historical analysis, they hint at a personality that was both disciplined and deeply engaged with his artistic pursuits. His dedication to his craft and his meticulous approach to his subjects certainly suggest a focused and energetic individual.

Influence and Lasting Legacy

Jacques Raymond Brascassat's influence extended to his students and contemporaries. Jean-Ferdinand Chaigneau (also referred to as Jean-François Chaigneau in some sources) was one of his notable pupils. Chaigneau, who also became known for his animal paintings, particularly sheep, acknowledged Brascassat's profound impact, especially his emphasis on the love of nature and keen observation. While Chaigneau later developed his own distinct, often more sensitive and atmospheric style, the foundation laid by Brascassat's teaching was evident.

Brascassat's work occupies an interesting position in 19th-century French art. He was not a revolutionary figure in the mold of Gustave Courbet, who radically challenged academic conventions with his unvarnished Realism, nor was he an Impressionist avant-gardist. Instead, Brascassat operated successfully within the academic system while simultaneously embracing the growing taste for realistic depictions of nature and rural life. His art can be seen as a bridge between the waning Neoclassical tradition and the ascendant Realist movement.

His specialization in animal painting contributed to the elevation of this genre in France. Alongside artists like Bonheur, Troyon, and the sculptor Barye, Brascassat helped to establish animal painting as a respected and popular field, moving beyond mere decorative or anecdotal depictions to create works of genuine artistic merit and emotional depth. His influence can also be seen in the broader context of landscape painting, where his meticulous rendering and appreciation for specific locales resonated with the era's increasing focus on national landscapes and naturalistic representation. Other artists who explored similar themes of rural life and animal subjects, though perhaps with different stylistic approaches, include Charles Jacque, known for his etchings and paintings of sheep and farmyard scenes.

Conclusion: An Enduring Contribution

Jacques Raymond Brascassat passed away in Paris on February 28, 1867. He left behind a significant body of work that continues to be appreciated for its technical excellence, its honest portrayal of the natural world, and its sensitive depiction of animal life. His paintings, found in major museum collections in France, including the Louvre in Paris, the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux, and the Musée de Tessé in Le Mans, stand as a testament to his skill and dedication.

As an art historian, one recognizes Brascassat as a master of his chosen genres. He successfully navigated the complex art world of 19th-century France, earning accolades and respect while staying true to his artistic vision. His ability to fuse academic discipline with a profound love for nature, particularly evident in his nuanced portrayals of animals and his carefully constructed landscapes, ensures his enduring place in the history of French art. His work offers a valuable window into the artistic currents of his time, reflecting a period where tradition and innovation coexisted and where the beauty of the natural world found eloquent expression on canvas.