Introduction: A Unique Vision of the Waterways

James Bard (1815-1897) stands as a unique and indispensable figure in American art history. A largely self-taught marine artist born and based in New York City, Bard dedicated his long career to meticulously documenting the burgeoning age of steam and sail on the waterways in and around his native city. Alongside his twin brother John for a significant portion of his early career, James Bard produced an astonishing volume of work, estimated at over 4,000 paintings, primarily focusing on the steamships, sailing vessels, and yachts that plied the Hudson River, Long Island Sound, and New York Harbor. While perhaps lacking the academic polish of some contemporaries, Bard's work possesses an undeniable clarity, precision, and historical value that makes it essential for understanding 19th-century American maritime life and technology. His paintings serve as vital visual records, capturing the pride and dynamism of a rapidly industrializing nation.

The Early Years: A Partnership Forged by Twinship

James Bard was born in New York City in 1815, along with his identical twin brother, John (1815-1856). Their artistic journey began remarkably early and was intrinsically linked. Growing up near the bustling shipyards and waterways of Manhattan provided endless inspiration. The brothers reportedly began collaborating on ship portraits around the age of twelve, circa 1827, demonstrating a precocious talent and shared passion for maritime subjects. This informal collaboration solidified into a formal partnership by 1831.

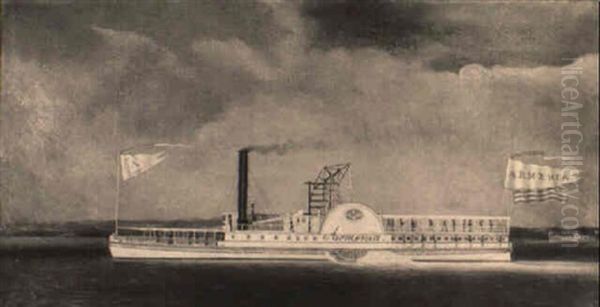

Working together, they established a reputation for creating detailed portraits of the vessels navigating the local waters. Their early works were predominantly watercolors, characterized by a careful, if somewhat naive, rendering of ships, often shown in profile against a simple backdrop. They signed their joint works typically as "J&J Bard" or sometimes "J Bard, Picture Painter," making attribution of specific hands difficult for this period. This partnership was crucial in establishing their presence among ship owners, captains, and builders who became their primary patrons.

The Bard brothers specialized in documenting the important vessels of their time, capturing the transition from sail to steam. Their paintings from this era are invaluable to maritime historians, offering detailed visual information about the construction, decoration, and operation of ships on Long Island Sound and the Hudson River. They captured the workhorses and the flagships, providing a broad cross-section of the era's maritime traffic.

The End of a Partnership

The productive partnership between James and John Bard lasted for nearly two decades. However, around 1849 or 1850, the collaboration ceased. Sources indicate that John left the partnership, although the precise reasons remain somewhat unclear. John Bard passed away only a few years later, in 1856. From this point forward, James Bard continued his artistic career independently, building upon the foundation they had established together but developing his own distinct, mature style. The works signed simply "J. Bard" or "James Bard" date from this solo period.

Artistic Method: Precision Born of Observation

James Bard's approach to his art was deeply rooted in direct observation and a commitment to accuracy. As a self-taught artist, he developed his techniques through practice and close study rather than formal academic training. His method involved frequent visits to the shipyards and docks of New York. He wasn't content with capturing a mere likeness; he sought to record the vessel's specific details with near-photographic precision, long before photography became commonplace or practical for such subjects.

Bard would meticulously measure the ships he intended to paint, taking down notes on their dimensions, proportions, hull colors, deck arrangements, and decorative features. This empirical approach ensured that his finished paintings were remarkably accurate representations, valued not only as art but as technical documents. Shipbuilders and owners appreciated this fidelity, as the paintings served as proud records of their vessels. This dedication to detail is a defining characteristic of his work, setting him apart from marine artists who prioritized atmospheric effects or dramatic compositions over factual representation.

While he began primarily with watercolors, Bard increasingly adopted oil painting starting around 1845. His oil paintings allowed for richer colors and larger formats, often commissioned for display in shipping offices or the homes of wealthy patrons. Regardless of the medium, his style remained focused on clarity and precision. The ships themselves are always the heroes of his compositions, rendered with crisp lines and bright, clear colors.

Style Characteristics: Naive Charm and Documentary Zeal

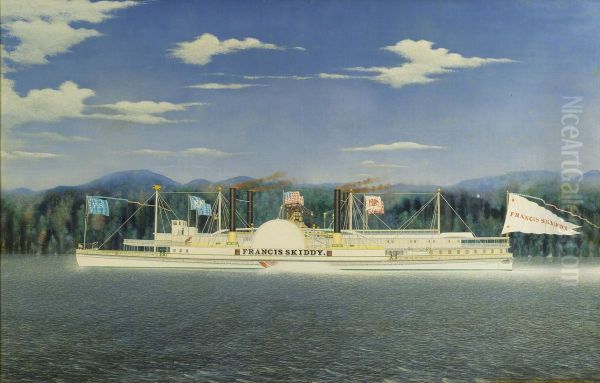

The artistic style of James Bard is often described as "primitive" or "naive," terms that acknowledge his lack of formal training but shouldn't detract from his skill or the effectiveness of his work. His paintings typically feature vessels depicted in side profile, steaming or sailing across the water. The backgrounds are often simplified, sometimes featuring recognizable landmarks along the Hudson or New York Harbor, but the primary focus is invariably the ship itself.

Bard's compositions are usually straightforward and balanced. Water is often rendered with stylized, repetitive wave patterns, and skies are typically clear or feature simple cloud formations. Perspective can sometimes appear slightly flattened, and figures aboard the ships are rendered simply, yet these qualities contribute to the direct, honest charm of his work. There's an intensity of focus and a clarity of purpose that transcends academic conventions.

A notable feature in many Bard paintings is the prominent, often oversized, depiction of the American flag, waving crisply from the stern or masthead. This reflects the strong patriotic sentiment of the era and the pride associated with American maritime enterprise. His later works, particularly after 1865, are sometimes noted as becoming slightly more "subdued," perhaps reflecting a change in personal style or patronage demands, but the core commitment to detailed ship portraiture remained constant throughout his long solo career.

Chronicler of the Steam Age: Subject Matter

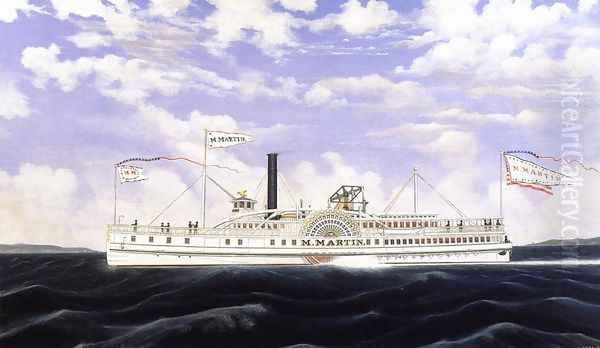

James Bard's oeuvre provides an unparalleled visual chronicle of American maritime technology and commerce during a period of profound transformation. His primary subjects were the vessels that defined the era on New York's waterways. He is particularly renowned for his depictions of steamboats – the sidewheelers and early propeller-driven ships that revolutionized transportation and commerce on rivers like the Hudson. He painted famous Hudson River Day Liners, workaday ferries, powerful towboats, and elegant steam yachts.

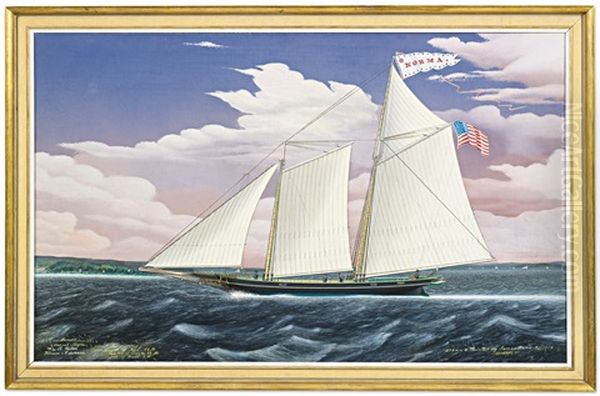

Beyond steam, Bard also depicted a variety of sailing craft, including majestic schooners, sloops, and smaller pleasure yachts. His interest extended to virtually every type of vessel active in the region. He captured them underway, often with smoke billowing from stacks or sails catching the wind, conveying a sense of energy and purpose. These were not just static portraits; they depicted working vessels in their natural environment.

The settings for his paintings were the waters he knew intimately: the broad expanse of the Hudson River, the busy traffic of New York Harbor, and the waters of Long Island Sound. By documenting the specific ships that navigated these routes, Bard inadvertently recorded the economic lifeblood of New York and the technological advancements that were changing the face of America. His work captures the optimism and mechanical ingenuity of the 19th century.

The Prolific Solo Career

After his partnership with John ended around 1850, James Bard embarked on a remarkably productive solo career that spanned nearly five decades. He continued to receive commissions from the same network of patrons: ship owners, captains, naval architects, and prominent businessmen, including figures associated with Cornelius Vanderbilt. His reputation for accuracy made him the go-to artist for anyone wanting a definitive portrait of their vessel.

Bard maintained an astonishing output during these years. While the figure of over 4,000 paintings likely includes works from the partnership period, James alone is credited with thousands of works. He painted until the very end of his life, with his last known dated work being from 1896, the year before his death. This sustained productivity underscores his dedication to his craft and the continued demand for his specialized skill.

His solo works continued to refine the style established earlier, with perhaps a greater confidence in the handling of oil paint and larger compositions. He remained committed to the side-profile view and meticulous detail, ensuring his works retained their documentary value even as he matured as an artist. He became the undisputed master of the American steamboat portrait.

Representative Works: Icons of the Waterways

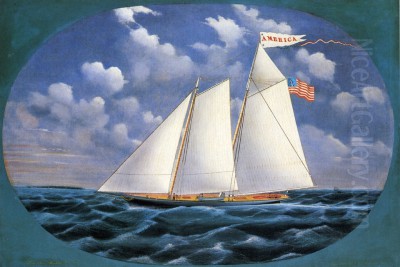

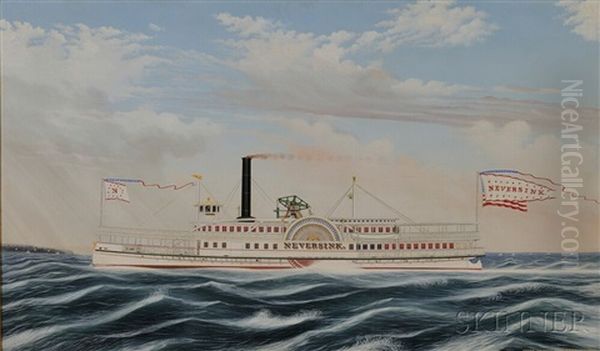

Among the vast number of works attributed to James Bard (and the earlier J&J Bard partnership), several stand out as representative examples of his style and subject matter:

Steamboat Utica (circa 1836): An early example, likely a collaboration with John, showcasing their detailed watercolor technique applied to a prominent Hudson River steamboat. It exemplifies their early focus on capturing the specific architecture of these vessels.

Chrystenah (various dates): Bard painted this popular and long-lived Hudson River steamboat multiple times over its career, documenting its appearance and modifications. These paintings highlight his role in recording the life history of individual vessels.

Milton (date unknown): Another example of a typical Bard steamboat portrait, likely showing a vessel known for its service on local routes, rendered with his characteristic precision.

Thomas P. Way (1873): This oil painting of a sidewheeler towboat achieved a high price (5,500) at a James Julia auction, demonstrating the market value placed on Bard's work. It showcases his mature oil technique and detailed rendering of a working vessel.

The Schooner Norma (1888): Fetching 0,000 at a Christie's auction, this work shows Bard's skill extended to sailing vessels as well. It captures the grace of the schooner rig with his typical attention to detail.

Portrait of the Sidewheeler Steamboat NEVERSINK (1864): Even works noted as having condition issues, like this one sold at Skinner Auctioneers, attract attention, indicating the strong collector interest in documented Bard paintings.

These examples, among many others, illustrate Bard's dedication to capturing the specific identity and character of each vessel he painted.

Patronage, Reception, and Market Value

James Bard's patrons were primarily individuals directly involved in the maritime world: the owners who commissioned the ships, the captains who commanded them, the builders who constructed them, and the agents who managed their operations. They sought his work not necessarily as high art in the academic sense, but as accurate and proud representations of their vessels and enterprises. His paintings often hung in the offices of shipping companies, in captains' cabins, or in the homes of those connected to the maritime trade.

During his lifetime, Bard achieved a solid reputation within this specific niche. While he did not exhibit widely in the major art academies or salons alongside painters like Frederic Edwin Church or Albert Bierstadt, his work was known and valued by those who mattered most to his business – the maritime community. His style, sometimes deemed "primitive" by critics looking for the atmospheric effects of J.M.W. Turner or the luminist tranquility of Fitz Henry Lane, was precisely what his patrons desired: clarity, detail, and an honest depiction of their prized vessels.

In the decades following his death, Bard's work, like that of many specialized or self-taught artists, faded somewhat from public view. However, beginning in the mid-20th century, collectors and maritime historians rediscovered his paintings. They recognized the immense historical value and the unique artistic charm of his work. This led to a significant reassessment of his contribution and a dramatic increase in the market value of his paintings. Today, his works are highly sought after at auction, commanding prices that reflect his status as the preeminent visual chronicler of New York's age of steam, rivaling prices for works by other noted American marine painters like James E. Buttersworth or Antonio Jacobsen, the latter often seen as Bard's successor in the sheer volume of ship portraiture.

Historical Significance: A Window into the Past

The primary significance of James Bard's work lies in its immense value as historical documentation. He created an unparalleled visual archive of 19th-century American watercraft, particularly the steamboats that transformed transportation and commerce. In an era before widespread photography, his detailed and accurate paintings provide invaluable information for maritime historians, naval architects, and ship modelers studying the design, construction, and appearance of these vessels.

Bard captured a pivotal moment in American history – the rise of industrialization and the dominance of steam power. His paintings are imbued with the energy and optimism of that era. They document not just the ships themselves, but the economic activity and technological pride of New York and the nation. Looking at a Bard painting offers a direct glimpse into the bustling maritime world of the Hudson River and New York Harbor over 150 years ago.

While artists of the Hudson River School, such as Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, captured the majestic landscapes through which these vessels traveled, Bard focused squarely on the vessels themselves, the products of human ingenuity navigating those waters. His work complements the landscape tradition by providing a detailed look at the era's technology. Similarly, while genre painters like George Caleb Bingham depicted life along the rivers, Bard concentrated on the primary vehicles of that life. His singular focus gives his work its unique power and importance. He stands apart from the more atmospheric or romantic marine painters, offering instead a clear, factual record, much like the earlier, precise work of Robert Salmon in Boston harbor, but focused on a later era and different types of vessels.

Contextualizing Bard: Comparisons with Contemporaries

Placing James Bard within the broader context of 19th-century American art helps to appreciate his unique contribution. He was contemporary with the major figures of the Hudson River School, whose focus was primarily landscape, though ships often featured incidentally in the works of artists like Sanford Robinson Gifford. Bard's meticulous, documentary style contrasts sharply with their romantic or luminist approaches.

Compared to other specialized marine painters, Bard holds a distinct position. Fitz Henry Lane, for example, shared an interest in accurate ship depiction but bathed his scenes in a serene, atmospheric light, emphasizing mood over mechanical detail. James E. Buttersworth captured the dynamism and excitement of yacht racing, often using more dramatic compositions and looser brushwork than Bard. Antonio Jacobsen, working slightly later and also incredibly prolific, produced ship portraits that are detailed but often considered somewhat more formulaic than Bard's best work. William Bradford, known for his dramatic Arctic scenes, depicted ships battling the elements, a far cry from Bard's typically calm water settings.

Bard's self-taught background and detailed, somewhat stylized rendering connect him to the American folk art tradition, exemplified by artists like Edward Hicks. While Bard's work was commercial portraiture rather than purely personal expression, it shares a directness and intensity of vision often found in folk art. Unlike academically trained artists, Bard developed his own solutions to representational challenges, resulting in a style that is both highly personal and perfectly suited to his documentary purpose. Even the later marine works of Winslow Homer, while powerful and evocative, stem from a different artistic tradition and sensibility altogether. Bard remains unique in his unwavering focus and meticulous method.

Later Life, Death, and Rediscovery

James Bard remained dedicated to his craft throughout his life. He continued painting actively into his eighties, a testament to his enduring passion and the continued, if perhaps diminished, demand for his work as photography began to supplant painted ship portraits. Despite his prolific output and the commissions he received, Bard apparently did not achieve significant financial success or security.

He passed away in White Plains, New York, in 1897. Poignantly, this dedicated chronicler of America's maritime pride died in relative poverty and was buried in a potter's field, a cemetery reserved for the unknown or indigent. This suggests that while his work was valued by a specific clientele, it did not translate into lasting wealth or widespread fame during his later years.

For several decades after his death, James Bard was largely forgotten by the broader art world. His rediscovery began in the mid-20th century, driven by maritime historians and collectors of Americana who recognized the unique historical and artistic value of his paintings. Exhibitions, publications, and rising auction prices gradually brought his work back into the spotlight. A major retrospective exhibition, likely the one held at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (formerly the National Museum of American Art) in 1987, solidified his reputation and introduced his work to a wider audience. Today, he is acknowledged as a master in his specialized field.

Collections and Exhibitions: Where to See Bard's Work

The most significant public collection of James Bard's work is held at The Mariners' Museum and Park in Newport News, Virginia. This institution houses a large number of his paintings, both watercolors and oils, spanning his career and including works from the partnership with his brother John. It is the premier destination for anyone wishing to study his art in depth.

Works by James Bard are also found in other major museum collections, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., the New-York Historical Society, the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, and various local historical societies along the Hudson River.

Beyond public museums, Bard's paintings frequently appear on the art market. Major auction houses like Christie's, Sotheby's, Skinner Auctioneers, and formerly James Julia Auctioneers, regularly handle his works, often achieving strong prices that reflect the ongoing collector demand. These sales and occasional gallery exhibitions continue to affirm his importance and keep his unique vision before the public eye.

Conclusion: An Enduring Legacy in American Art

James Bard occupies a vital and distinct niche in the history of American art. As a self-taught artist driven by a passion for accuracy and a deep familiarity with his subject matter, he created an unparalleled visual record of the steamboats and sailing vessels that defined New York's waterways during the 19th century. Working first with his twin brother John, and then independently for nearly fifty years, he produced thousands of detailed ship portraits commissioned by those who built, owned, and operated these vessels.

While his style may be termed "naive" by some academic standards, its clarity, precision, and documentary integrity are precisely what make his work so valuable. Bard captured the pride, technology, and dynamism of the American steam age with an unwavering focus. Though he died in obscurity, his work has been rediscovered and is now celebrated for its historical importance and its unique artistic charm. James Bard remains the foremost painter of the American steamboat, leaving behind a legacy that continues to inform and fascinate historians, collectors, and admirers of maritime heritage.