Alfred Wallis stands as one of the most remarkable and unique figures in twentieth-century British art. A mariner and scrap merchant for most of his life, he turned to painting only in his later years, driven by loneliness and memory. Without formal training, he developed a distinctive, direct style that captured the essence of his life experiences, particularly his deep connection to the sea and the Cornish coast. His work, initially overlooked, was later championed by modernist artists and continues to fascinate audiences with its raw authenticity and expressive power. He became an emblematic figure associated with the burgeoning art colony in St Ives, Cornwall, influencing a generation of artists who admired his untutored vision.

Early Life and Maritime Career

Alfred Wallis was born in Devonport, Devon, in 1855. His early life was marked by the sea and manual labour. Sources suggest he may have initially apprenticed as a basket maker. However, the call of the ocean was strong, and by the early 1870s, he had become a mariner. His time at sea was extensive; he worked on vessels that crossed the vast Atlantic Ocean, experiencing the demanding life of a deep-sea fisherman.

His voyages took him far from England, including trips to the fishing grounds off Newfoundland. Later, he transitioned to working in the local fishing industry closer to home, operating out of Penzance in Cornwall. This long and intimate relationship with the sea, the boats, the weather, and the coastal communities would profoundly shape the subject matter of his future artistic endeavours. His knowledge wasn't academic; it was born from direct, lived experience.

In 1890, Wallis made a significant move, relocating to St Ives, Cornwall. This picturesque fishing town would become his home for the remainder of his life and the backdrop for much of his art. In St Ives, he established himself not as a fisherman, but as a marine scrap merchant. He ran a business called 'Wallis, Alfred, Marine Stores Dealer', buying and selling salvaged items like iron, ropes, and sailcloth – materials intrinsically linked to the maritime world he knew so well. He continued this trade until his retirement around 1912.

The Turn to Art

Wallis's life took a pivotal turn following the death of his wife, Susan, in 1922. He was in his late sixties, retired, and facing profound loneliness. It was in this context, seeking solace and occupation, that he began to paint. He famously stated he took up painting "for company." It wasn't a pursuit driven by artistic ambition in the conventional sense, but rather an intuitive response to loss and a way to populate his world with the memories and experiences that defined him.

Entirely self-taught, Wallis had no preconceived notions about artistic conventions or techniques. He didn't attend art school, read art theory, or consciously align himself with any artistic movement. His approach was purely instinctual, drawing directly from his memories of his life at sea and his observations of the St Ives harbour and coastline. This lack of formal training became the bedrock of his unique and powerful style.

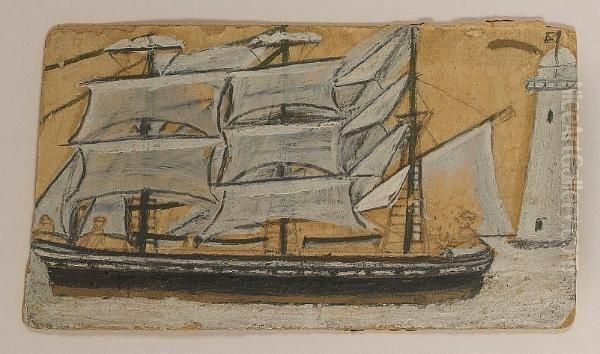

He painted prolifically, using whatever materials came to hand, often reflecting his background as a scrap merchant. His canvases were frequently irregular pieces of cardboard, packing boxes, scraps of wood, or even old jars. He used common household or ship's paints, often in a limited palette dominated by earthy tones, blacks, whites, and blues, applying them directly and vigorously.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Alfred Wallis is celebrated as a prime example of a "naïve" or "primitive" artist. His style is characterized by a deliberate disregard for academic conventions like linear perspective and realistic scale. Instead, he organized his compositions based on memory, emotion, and the perceived importance of the elements depicted. Objects, such as a prominent ship or a lighthouse, might be rendered larger than geographically smaller but less significant features like houses in the background.

His paintings often possess a map-like quality, depicting scenes from multiple viewpoints simultaneously or presenting a flattened, bird's-eye perspective of harbours and coastlines. This approach allowed him to convey a comprehensive sense of place and experience, rather than a single, fixed snapshot in time. The horizon line might curve, landmasses tilt, and the sea itself becomes a dynamic, living entity within the composition.

The application of paint is typically direct and unrefined, contributing to the raw energy of his work. Shapes are simplified, outlines are strong, and there is little interest in subtle modelling or chiaroscuro. The focus is on conveying the essential form and character of his subjects – the sturdy resilience of a fishing boat, the looming presence of a lighthouse, the enclosure of a harbour wall. His art is less about representation and more about evocation and personal testimony.

Materials and Methods

Wallis's choice of materials is integral to understanding his art and his life. His background as a scrap merchant undoubtedly influenced his resourcefulness. He rarely, if ever, used conventional artist's canvases or prepared boards. Instead, he embraced the found object, painting on discarded cardboard boxes (often with the original text or labels showing through), irregularly shaped pieces of wood, or even old jugs and containers.

This use of unconventional supports gives his work a distinct physical presence. The irregular shapes of the cardboard or wood often dictated or influenced the composition itself, creating a dynamic interplay between the painted image and the object it inhabits. The texture of the materials – the grain of the wood, the rough surface of the card – becomes part of the artwork's fabric.

He primarily used marine paints or common household paints, the kind readily available to a fisherman or ship chandler. His palette was often restricted, favouring the colours of the working harbour: blacks, greys, whites, sea-greens, blues, and earthy browns. This limited range, however, was used with great expressive force, contributing to the stark, powerful atmosphere of his paintings.

Themes and Subjects

The sea, in all its forms, is the dominant theme in Alfred Wallis's work. Having spent decades as a mariner, his understanding of the ocean, its moods, and the vessels that sailed upon it was profound and deeply personal. His paintings are populated with the ships he knew: sturdy fishing luggers with their distinctive sails, early steamships belching smoke, schooners navigating coastal waters.

He painted the harbours and coastlines of Cornwall, particularly St Ives and Penzance, from memory. These were not picturesque tourist views but working environments, depicted with an insider's knowledge. Lighthouses, crucial navigational aids, feature prominently, often standing as stoic sentinels against the elements. Houses cluster along the harbour edges, sometimes depicted simply, almost symbolically.

Wallis painted what he knew and remembered. His art was a form of storytelling, recounting his experiences ("what use To Bee"). Works like Voyage to Labrador likely recall specific, perhaps challenging, journeys from his past. There is often a strong sense of narrative, even in seemingly simple compositions. Religious belief also subtly informed some works, reflecting his personal piety. Ultimately, his subjects were drawn from the fabric of his own life, rendered through the filter of time and memory.

Discovery and Recognition

For several years, Alfred Wallis painted in relative obscurity, known perhaps only to his immediate neighbours in St Ives. His artistic life changed dramatically in August 1928. Two young, forward-thinking artists from London, Ben Nicholson and Christopher Wood, were visiting St Ives and happened upon Wallis's cottage. Peering through his open door or window, they saw his paintings pinned to the walls.

Nicholson and Wood were immediately struck by the directness, vitality, and untutored authenticity of Wallis's work. It resonated with their own modernist sensibilities and their search for art forms free from academic constraints. They recognized in Wallis an artist of genuine, albeit unconventional, talent. They befriended the elderly painter, bought some of his works, and became his champions.

Through Nicholson and Wood, Wallis's art was introduced to a wider, more sophisticated audience in London and beyond. They promoted his work within avant-garde circles, including the influential Seven and Five Society, of which Nicholson was a member. Wallis became associated with the burgeoning St Ives School of artists, although he remained personally detached from its social dynamics. His discovery highlighted the modernist interest in "primitive" and "outsider" art, valuing intuition and raw expression over technical polish.

Life in St Ives and Later Years

Despite the interest shown by Nicholson, Wood, and other artists and collectors like Jim Ede (who later founded Kettle's Yard gallery in Cambridge, a major repository of Wallis's work), Alfred Wallis's material circumstances did not significantly improve. He continued to live a simple, somewhat reclusive life in his small cottage on Back Road West in St Ives.

He was known to be deeply religious and sometimes suspicious of others, perhaps wary of the attention his art brought him. While he appreciated the friendship of Nicholson and others, he seemed largely uninterested in the broader art world or the theoretical discussions surrounding his work. He continued to paint because it was his way of connecting with his past and coping with his present.

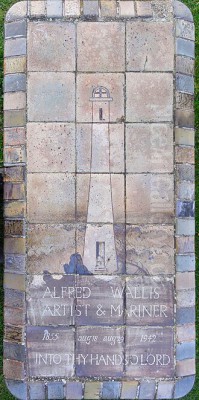

Tragically, his later years were marked by increasing poverty and frailty. As his health declined, he was eventually admitted to the Madron Public Assistance Institution, the local workhouse, near Penzance. It was here, far from the sea views of St Ives that had filled his canvases, that Alfred Wallis died in 1942. His grave in Barnoon Cemetery, overlooking Porthmeor Beach and the Tate St Ives gallery, features a gravestone decorated with ceramic tiles made by the renowned potter Bernard Leach, depicting a tiny mariner beneath a lighthouse – a poignant tribute organised by his artist admirers. The contrast between his impoverished end and his posthumous artistic acclaim remains a striking aspect of his story.

Influence on Other Artists

Alfred Wallis's impact on subsequent generations of artists, particularly those associated with St Ives, was profound, albeit complex. His most immediate and significant influence was on Ben Nicholson and Christopher Wood, the artists who discovered him. They were inspired by the directness, the flattened perspective, and the innate sense of design in Wallis's work. Nicholson, in particular, incorporated elements of Wallis's textural surfaces and simplified forms into his own developing abstract language. Wood's paintings also show a clear debt to Wallis's maritime themes and naïve figuration before Wood's untimely death in 1930.

Wallis's art became a touchstone for authenticity and intuitive expression for many artists drawn to St Ives, which was rapidly becoming a centre for British modernism. Figures like Barbara Hepworth (Nicholson's second wife) and the Russian Constructivist Naum Gabo, who arrived in St Ives shortly before World War II, were certainly aware of Wallis and the high regard in which Nicholson held him. While their own abstract styles differed greatly, Wallis represented a connection to the local landscape and a spirit of unmediated creativity that was part of the St Ives ethos.

Later generations of St Ives artists, such as Peter Lanyon, Patrick Heron, Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, and Terry Frost, inherited this legacy. While their work evolved in diverse directions, Wallis remained a foundational figure, embodying the spirit of place and the power of direct, personal vision. Critics like Adrian Stokes wrote perceptively about his work, further cementing his reputation. Artists like Margaret Mellis also collected and were inspired by his work. Even figures primarily known for other crafts, like the potter Bernard Leach, recognised Wallis's unique artistic contribution. His influence extended beyond St Ives, contributing to the broader appreciation of naïve and outsider art throughout the 20th century, alongside international figures like Henri Rousseau. Winifred Nicholson, Ben Nicholson's first wife and a notable painter herself, also knew and appreciated Wallis's work.

Representative Works

While dating Wallis's work precisely is often difficult as he rarely titled or dated his pieces, several paintings are frequently cited as representative of his style and themes.

Five Ships – Mount's Bay (or similar titles describing multiple ships in a harbour setting, often St Ives or Penzance) exemplifies his approach to maritime scenes. Such works typically show several vessels – often a mix of sailing ships and steamers – arranged within the protective curve of a harbour wall or against a backdrop of simplified houses. The perspective is often flattened, the scale intuitive, capturing the busy yet ordered life of the port through Wallis's memory.

Voyage to Labrador (c. 1935-36) is a more narrative piece, likely recalling one of his transatlantic journeys. It conveys the vastness and potential danger of the open ocean, often depicting a solitary ship against a dramatic sea and sky. These works showcase his ability to distill powerful memories and emotions into seemingly simple compositions.

Two Boats captures his focus on the essential forms of the vessels he knew so well. Whether depicting them at sea or moored in the harbour, Wallis imbues the boats with character, treating them almost as sentient beings shaped by their function and the environment.

Other common subjects include specific landmarks like the St Ives Lighthouse, depictions of Houses at St Ives, or compositions focusing on the dynamic relationship between land and sea. Each work, regardless of specific title, reflects his core concerns: memory, maritime life, and the Cornish environment, rendered in his unmistakable, direct style.

Legacy and Evaluation

Alfred Wallis died in poverty, largely unrecognized by the general public during his lifetime. However, thanks to the advocacy of Ben Nicholson, Christopher Wood, Jim Ede, and others, his work was preserved and its reputation grew steadily after his death. Today, he is considered a major figure in British modern art, not as a trained modernist, but as a unique visionary whose work ran parallel to and sometimes influenced mainstream developments.

He is celebrated as one of Britain's foremost naïve artists. His paintings are valued for their honesty, their raw expressive power, and their direct connection to a life lived intensely through maritime experience. His work demonstrates that artistic significance is not solely dependent on formal training or adherence to established movements, but can arise from authentic personal vision and deep-seated memory.

His legacy is firmly tied to St Ives. He is seen as one of the key figures who put the town on the artistic map, attracting other artists and contributing to its identity as an international art centre. Major collections of his work are held at Tate St Ives, which overlooks the cemetery where he is buried, and at Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge, the former home of Jim Ede, which offers an intimate setting to appreciate his art alongside modernist contemporaries. His paintings continue to be exhibited internationally and inspire artists, critics, and the public with their enduring, untamed spirit.

Conclusion

Alfred Wallis's journey from fisherman and scrap merchant to celebrated artist is a compelling narrative of late-blooming creativity born from experience and solitude. His paintings, created "for company" on scraps of cardboard and wood, offer a unique window into the maritime world of Cornwall in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Untouched by academic rules, his art speaks with a directness, honesty, and emotional intensity that captivated modernist artists and continues to resonate today. He remains a testament to the power of untutored vision and the profound connection between life, memory, and art, securing his place as a vital and original voice in British art history.