Introduction: A Founding Visionary

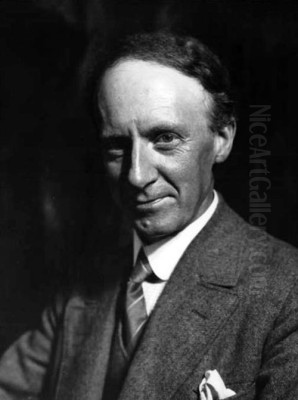

James Edward Hervey MacDonald, universally known in Canadian art history as J.E.H. MacDonald, stands as a pivotal figure in the development of a distinctly Canadian school of painting. Born in Durham, England, on May 12, 1873, he emigrated with his family to Canada at the age of 14, settling in Hamilton, Ontario. His life, spanning until his death on November 26, 1932, was dedicated to capturing the spirit and substance of the Canadian landscape, particularly the rugged wilderness of Ontario. As a founding member of the iconic Group of Seven, MacDonald was not only a prolific painter but also a respected designer, poet, and influential educator, leaving an indelible mark on the nation's cultural identity.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

MacDonald's artistic inclinations emerged early. After moving to Hamilton, he began his formal art training, studying at the Hamilton Art School. His family's subsequent move to Toronto allowed him to continue his education at the Central Ontario School of Art and Design (now OCAD University). This period was crucial for honing his technical skills in drawing and painting, laying the groundwork for his future career. However, like many artists of his time, financial necessity initially led him towards commercial art.

He apprenticed at the Toronto Lithographing Company, gaining practical experience in the graphic arts. This was followed by a significant period working at Grip Ltd., a prominent commercial design firm in Toronto, starting around 1895. Grip Ltd. became an unexpected crucible for Canadian art, fostering a community of artists who would later form the core of the Group of Seven. It was here that MacDonald sharpened his design sensibilities and, crucially, met and worked alongside fellow artists like Tom Thomson, Arthur Lismer, Frederick Varley, Franklin Carmichael, and Frank Johnston. The collaborative and creatively stimulating environment at Grip undoubtedly played a role in shaping their shared artistic aspirations.

The Influence of Design and Early Styles

During his years at Grip Ltd., MacDonald rose to the position of Head Designer. His work in commercial art was highly regarded, and his design aesthetic was influenced by the burgeoning Arts and Crafts movement, particularly the ideals championed by the British designer and writer William Morris. This influence is visible in MacDonald's attention to detail, his interest in decorative patterns, and his integration of lettering and design, which would later surface in his book designs and calligraphy.

His early painting style reflected the prevailing tastes of the time, showing an affinity for the detailed realism and atmospheric effects common in late 19th-century landscape painting. However, exposure to European art movements, particularly Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, began to shift his approach. The works of artists like Claude Monet and Vincent van Gogh, known through reproductions and exhibitions, encouraged a bolder use of colour and a more expressive application of paint. MacDonald started experimenting with capturing the transient effects of light and atmosphere, moving away from purely topographical representation towards a more personal interpretation of nature.

A Full-Time Commitment to Painting

By 1911, MacDonald felt a growing desire to dedicate himself entirely to painting. Supported by his wife, Joan Lavis (whom he married in 1899), and driven by an increasing passion for capturing the Canadian landscape on its own terms, he made the bold decision to leave the security of his commercial art career at Grip Ltd. This marked a turning point, allowing him the freedom to travel, sketch, and develop his unique artistic voice.

His early focus was often on the gentler landscapes around Toronto and Georgian Bay. Works from this period show his evolving style, incorporating brighter palettes and looser brushwork. He was deeply influenced by the writings of American transcendentalist authors like Henry David Thoreau and Walt Whitman, whose reverence for nature resonated with his own spiritual connection to the wilderness. He sought to convey not just the visual appearance of the landscape, but also the feelings it evoked – a sense of awe, solitude, and the inherent power of the natural world.

The Genesis of the Group of Seven

The desire to forge a distinctly Canadian art, free from European dominance, was a shared ambition among MacDonald and his colleagues from Grip Ltd. They felt that the Canadian landscape, particularly the rugged, untamed North, required a new visual language. MacDonald, along with Lawren Harris, became a key driving force behind the formation of what would become the Group of Seven. Harris's financial support and MacDonald's seniority and articulate vision were instrumental in uniting the artists.

They embarked on sketching trips together, most notably to the Algoma region of Ontario and later to the North Shore of Lake Superior. These expeditions were vital, providing firsthand experience of the wilderness that fueled their art. The artists shared ideas, critiqued each other's work, and developed a collective identity, even as their individual styles remained distinct. Tom Thomson, though never formally a member due to his untimely death in 1917, was a crucial catalyst and companion on many early trips, his bold style and deep connection to Algonquin Park profoundly influencing the group.

The first official exhibition of the Group of Seven was held at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario) in May 1920. The founding members were J.E.H. MacDonald, Lawren Harris, A.Y. Jackson, Frank Johnston, Arthur Lismer, Frederick Varley, and Franklin Carmichael. Their work, characterized by vibrant colour, bold forms, and a dramatic portrayal of the Canadian landscape, initially met with mixed reviews, with some critics finding it crude or harsh compared to traditional European styles. MacDonald, as one of the elder statesmen of the group, often acted as a spokesperson, defending their vision in writing and lectures.

Algoma: A Landscape of Inspiration

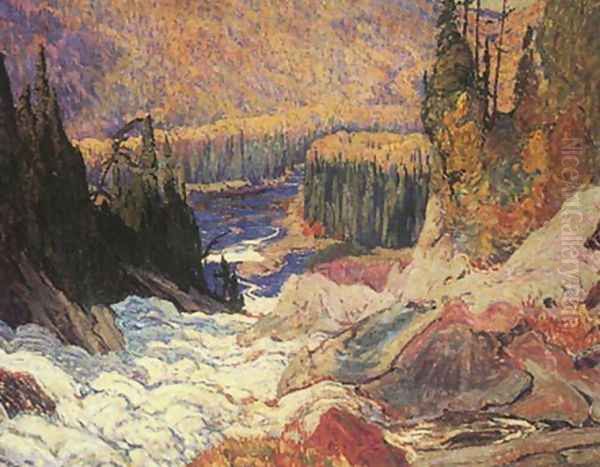

The Algoma region, accessible via the Algoma Central Railway, became a particularly fertile ground for MacDonald and other Group members like Harris, Jackson, and Johnston. Starting in 1918, they undertook several boxcar trips, using a specially outfitted railway car as a mobile studio. The dramatic scenery – vast forests, rolling hills, turbulent rivers, and the changing colours of the seasons – provided endless inspiration.

MacDonald's Algoma paintings are among his most celebrated works. He developed a distinctive style for depicting this region, characterized by rich, often autumnal colours, intricate compositions that captured the dense texture of the forest, and a sense of monumental scale. He employed strong brushwork and sometimes used impasto to convey the ruggedness of the terrain. These works moved beyond mere description to express a profound, almost spiritual connection to the land.

The Solemn Land: An Iconic Statement

Painted in 1921, The Solemn Land is perhaps MacDonald's most famous work from the Algoma period and a quintessential Group of Seven painting. It depicts a panoramic view of the Algoma wilderness, likely the Montreal River valley, under a vast, dynamic sky. The rolling hills are rendered in deep blues, purples, and russets, conveying a sense of ancient grandeur and quiet power. The dramatic interplay of light and shadow across the landscape, coupled with the swirling cloud formations, imbues the scene with emotional weight.

The title itself, The Solemn Land, reflects MacDonald's deep reverence for the wilderness. The painting is not just a landscape; it is an emblem of the Canadian spirit, representing the vastness, resilience, and inherent dignity the artists found in the northern environment. It embodies the Group's goal of creating art that was uniquely Canadian, rooted in the direct experience of the land. The work is now a treasured part of the collection at the National Gallery of Canada.

Mature Style and Celebrated Works

MacDonald's artistic output includes numerous significant paintings that showcase his evolving style and thematic concerns. Tracks and Traffic (1912), an earlier work, is notable for its depiction of an industrial subject – a railway cutting near High Park in Toronto. It demonstrates his ability to find artistic merit even in human-altered landscapes, using strong design principles likely honed during his commercial art career. The composition features bold lines and simplified forms, hinting at the stylistic direction he and the Group would later pursue more fully.

The Tangled Garden (1916), based on the garden behind his own home in Thornhill, Ontario, is another landmark piece. It is a riot of colour and texture, depicting sunflowers and other plants in a dense, almost overwhelming composition. The painting is celebrated for its vibrant palette and complex interplay of forms, pushing the boundaries of traditional landscape painting. It reflects an intense observation of nature combined with a decorative sensibility, possibly influenced by Post-Impressionist artists like Van Gogh, yet interpreted through MacDonald's unique vision. This work is also housed in the National Gallery of Canada.

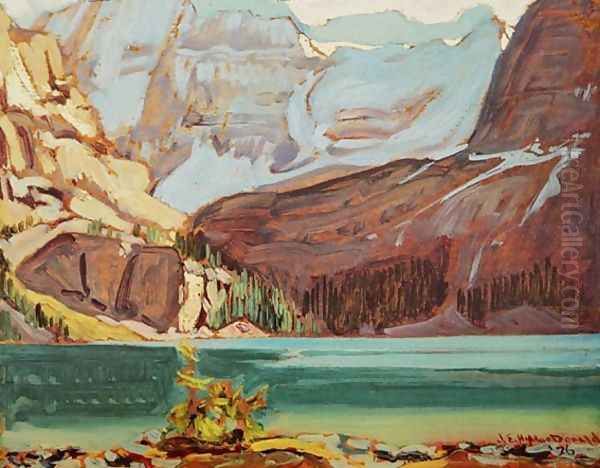

Mist Fantasy, Sand River, Algoma (1922) captures a different mood. Exhibited at the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in 1922 and acquired by the Art Gallery of Toronto, this painting showcases MacDonald's skill in rendering atmospheric effects. The soft, diffused light and ethereal quality of the mist enveloping the landscape create a poetic and dreamlike scene, contrasting with the more rugged depictions found in works like The Solemn Land. Other notable works include Forest Wilderness and numerous sketches and oil panels from his travels in Algoma, the Rockies, and Nova Scotia.

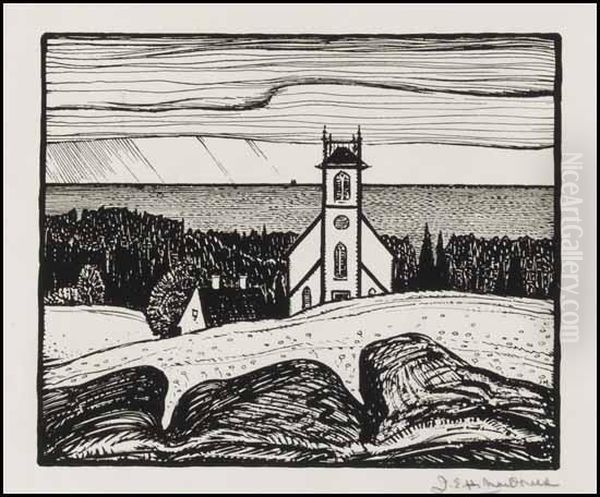

Design, Poetry, and Calligraphy

Throughout his life, MacDonald maintained his interest in design and the graphic arts. He believed in the integration of art into everyday life, consistent with the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement. He undertook commissions for book designs, illustrations, and murals, often incorporating his distinctive calligraphy. His lettering style was elegant and legible, reflecting his deep understanding of form and composition.

MacDonald was also a published poet. His collection of poems, West by East (1933), was published posthumously, featuring verses that often mirrored the themes found in his paintings – a deep love for nature, reflections on the Canadian landscape, and a sense of spirituality. His son, Thoreau MacDonald, became a renowned illustrator and designer in his own right, carrying on the family's artistic legacy, particularly in the field of book arts.

Educator and Mentor

In 1921, MacDonald joined the faculty of the Ontario College of Art (OCA, now OCAD University), initially as an instructor in decorative and commercial design. His extensive experience in both fine art and commercial design made him a valuable asset to the institution. He was known as a dedicated and inspiring teacher, influencing a generation of Canadian artists.

His commitment to art education culminated in his appointment as the Principal of OCA in 1928 (some sources say 1929), a position he held until his death. During his tenure, he worked to modernize the curriculum and championed the importance of Canadian art. His leadership role, however, combined with his continued painting and sketching trips, placed considerable demands on his time and energy. He was respected by students and faculty alike for his gentle demeanor, wisdom, and unwavering dedication to art.

Relationships within the Group

MacDonald's role within the Group of Seven was complex. As one of the eldest and most established members at its formation, he naturally commanded respect. He was often seen as a stabilizing influence and a thoughtful articulator of the Group's aims. His relationships with fellow members like Lawren Harris and A.Y. Jackson were built on mutual respect and shared artistic goals, forged through years of sketching trips and collaboration.

While the Group was founded on camaraderie, artistic differences and strong personalities inevitably led to internal dynamics that could include elements of friendly competition or differing viewpoints on artistic direction. MacDonald's style, often more decorative and detailed compared to the increasing austerity of Lawren Harris's later work, highlights the diversity within the Group. However, the primary narrative emphasizes collaboration and mutual support in their collective mission to define Canadian art. MacDonald was known to be encouraging to younger artists, both within the Group and among his students.

Exhibitions and Recognition

MacDonald's work was featured prominently in all the Group of Seven exhibitions from 1920 until the Group formally disbanded in 1933 (evolving into the larger Canadian Group of Painters). He also exhibited independently and with other societies, including the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts and the Ontario Society of Artists. His participation in the Arts and Letters Club of Toronto was significant, as the club served as an important meeting place and exhibition venue for the artists.

A key moment influencing his style, and that of Lawren Harris, was their visit to the exhibition of contemporary Scandinavian painting at the Albright Art Gallery (now Albright-Knox Art Gallery) in Buffalo, New York, in 1913. The bold colours and stylized depictions of northern landscapes by Scandinavian artists resonated with their own quest to portray the Canadian North, reinforcing their move towards a more expressive and less naturalistic style. MacDonald's work gained national recognition during his lifetime, with major institutions acquiring his paintings.

Personal Life and Final Years

J.E.H. MacDonald married Joan Lavis in 1899. Their son, Thoreau, born in 1901, became an important Canadian illustrator. They also had a second son, Concord, born in 1908, who sadly died in infancy in 1910, a loss that undoubtedly affected the family deeply. MacDonald was known as a quiet, thoughtful man, deeply committed to his family and his art.

The demands of his painting career, extensive travel for sketching, teaching responsibilities, and administrative duties as Principal of OCA eventually took a toll on his health. In 1931, he suffered a stroke. Although he partially recovered, his health remained fragile. He traveled to Barbados in the autumn of 1932, hoping the warmer climate would aid his recuperation, but suffered a second stroke there and died in Toronto shortly after his return, on November 26, 1932, at the age of 59.

Legacy and Collections

J.E.H. MacDonald's legacy is firmly cemented in Canadian art history. As a founding member of the Group of Seven, he played an indispensable role in shaping a national school of landscape painting. His works are celebrated for their technical skill, emotional depth, and powerful evocation of the Canadian wilderness. He successfully bridged the gap between commercial design and fine art, and his contributions as an educator shaped future generations.

His paintings remain highly sought after by collectors and institutions. Auction results for his works, such as the significant estimates for paintings like Lake O'Hara, demonstrate the enduring market value and appreciation for his art. His works are held in major public collections across Canada, including the National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa), the Art Gallery of Ontario (Toronto), the McMichael Canadian Art Collection (Kleinburg, specializing in the Group of Seven), and the Vancouver Art Gallery, ensuring his vision continues to be accessible to the public. He influenced countless Canadian artists, including figures like Emily Carr, who, while developing her own unique style, shared a similar spiritual connection to the landscape. MacDonald, alongside contemporaries like David Milne, helped define the visual identity of Canada in the early 20th century.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

James Edward Hervey MacDonald was more than just a landscape painter; he was a visionary who sought to capture the soul of Canada through its wilderness. His journey from commercial designer to leading fine artist, his foundational role in the Group of Seven, his evocative depictions of Algoma and other Canadian locales, and his dedication to teaching collectively represent a profound contribution to Canadian culture. His paintings, rich in colour, texture, and feeling, continue to resonate with viewers, offering a timeless connection to the "solemn land" that inspired him throughout his life. His work remains a cornerstone of Canadian art, a testament to the power of landscape to shape identity and inspire artistic expression.