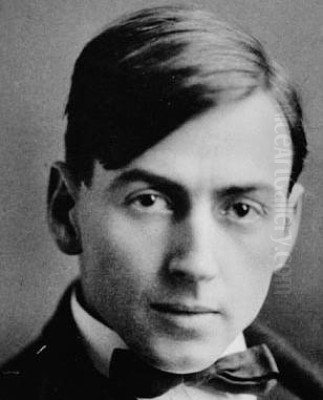

Tom Thomson stands as one of Canada's most revered and enigmatic artists. His vibrant, expressive depictions of the Northern Ontario wilderness fundamentally altered the course of Canadian art, paving the way for a distinctly national school of landscape painting. Though his professional painting career spanned a mere five years, cut tragically short by his mysterious death, Thomson's legacy endures, his works celebrated as iconic representations of the Canadian spirit and its profound connection to the untamed landscape. This exploration delves into the life, art, untimely death, and lasting influence of a man who, more than a century after his passing, continues to captivate and inspire.

Early Life and Artistic Awakenings

Thomas John Thomson, known universally as Tom Thomson, was born on August 5, 1877, near Claremont, Ontario, and grew up in Leith, near Owen Sound, on the shores of Georgian Bay. His upbringing in a rural environment fostered an early appreciation for nature, an interest that would later define his artistic output. He was one of ten children in a farming family, and his early life was not overtly indicative of the artistic giant he would become. He explored various pursuits, including a brief stint at a business college in Chatham, Ontario, and an attempt to enlist for the Boer War, from which he was turned away due to a medical condition (likely a lung ailment or a toe deformity).

Thomson's initial foray into the professional world was not in fine art but in the burgeoning field of commercial art and design. Around 1901, he moved to Seattle, Washington, where his older brother George was running a business school. There, Thomson worked as a commercial artist and engraver, likely for firms like Maring & Ladd (later Maring & Blake) and then the Seattle Engraving Company. This period provided him with foundational skills in design, composition, and the technical aspects of image reproduction, particularly photo-engraving. These skills, though commercially oriented, would subtly inform his later painterly practice.

By 1905, Thomson had returned to Canada, settling in Toronto. He found employment as a senior artist at Legg Brothers, a photo-engraving firm. His talent was evident, and in 1909, he moved to Grip Ltd., a prominent commercial art and design firm in Toronto. This move proved pivotal. Grip Ltd. was a creative hub, employing a remarkable cohort of artists who would later form the nucleus of the Group of Seven. It was here that Thomson's artistic sensibilities began to truly flourish, encouraged by colleagues who shared a passion for capturing the Canadian landscape.

The Influence of Grip Ltd. and the Shift to Fine Art

At Grip Ltd., Thomson worked alongside artists such as J. E. H. MacDonald, Arthur Lismer, Frederick Varley, and Franklin Carmichael. Frank Johnston and later Lawren Harris and A. Y. Jackson, though not all directly employed by Grip at the same time, were part of this burgeoning artistic circle. These men, inspired by European Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, as well as the decorative qualities of Art Nouveau, were beginning to question the prevailing academic art traditions in Canada, which often favored European subjects and styles. They sought a visual language that could express the unique character of the Canadian landscape – its ruggedness, its vastness, its vibrant seasonal changes.

Thomson, initially more focused on his design work, was gradually drawn into their enthusiasm for landscape painting. He began taking sketching trips, often with his Grip colleagues, to areas around Toronto, such as Lake Scugog and the Humber Valley. His early sketches show a developing eye for colour and composition, though still somewhat tentative compared to his later, bolder works. J. E. H. MacDonald, in particular, recognized Thomson's latent talent and encouraged him to pursue painting more seriously.

A significant turning point came in 1912. Thomson made his first extended trip to Algonquin Park, a vast, semi-wilderness area of forests, lakes, and rivers in Central Ontario. This trip was a revelation. The park's untamed beauty, its dramatic skies, and its ever-changing moods resonated deeply with Thomson. He found his true subject matter. That same year, he left Grip Ltd., though he continued to do freelance commercial work to support himself, and began to dedicate himself more fully to painting. His friend, the wealthy art patron Dr. James MacCallum, provided financial support, allowing Thomson to spend significant portions of each year, from spring to autumn, in Algonquin Park.

Algonquin Park: Muse and Sanctuary

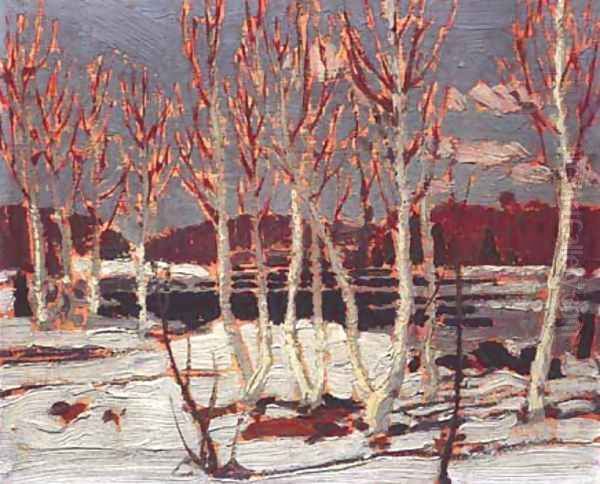

Algonquin Park became Tom Thomson's spiritual home and his open-air studio. From 1912 until his death in 1917, he spent the warmer months there, living a rugged life, canoeing, fishing, and working as a guide, all while sketching prolifically. He would typically produce dozens, sometimes hundreds, of small oil sketches on birch panels, usually 8 by 10 inches, directly from nature. These sketches, executed rapidly en plein air, captured the immediate impressions of light, colour, and atmosphere. They are characterized by their vibrant hues, bold brushwork, and an almost visceral connection to the subject.

During the harsh Canadian winters, Thomson would return to Toronto. He often rented a small shack behind the Studio Building, a purpose-built artists' space financed by Lawren Harris and Dr. MacCallum, which became a central meeting point for the artists who would form the Group of Seven. In this modest studio, Thomson would work up his small outdoor sketches into larger canvases. This process involved not just scaling up the sketches but reinterpreting them, often imbuing the larger works with a more symbolic or monumental quality.

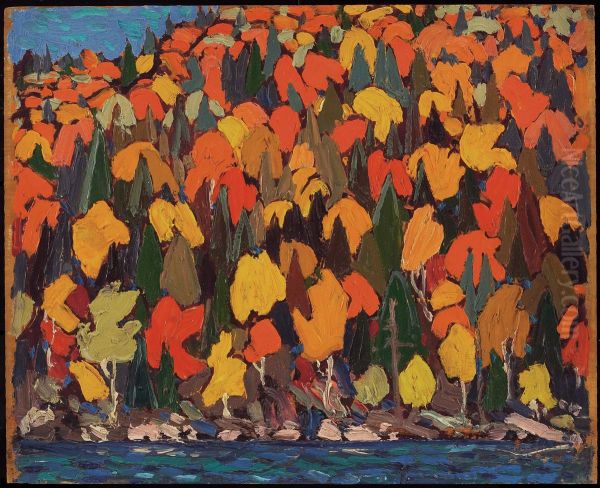

His life in Algonquin Park was one of deep immersion. He knew the park intimately – its waterways, its portages, its hidden corners. This profound familiarity allowed him to capture not just the visual appearance of the landscape but its inherent spirit. He painted the changing seasons with an unmatched intensity: the fresh greens of spring, the brilliant blues and whites of summer skies and water, the fiery reds, oranges, and yellows of autumn, and even the stark beauty of early winter. His connection to the park was more than just artistic; it was a way of life. He was a skilled woodsman, canoeist, and fisherman, respected by local guides and rangers.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Development

Tom Thomson's artistic style is unique and instantly recognizable, yet it also reflects a sophisticated assimilation of various contemporary artistic currents. He was largely self-taught as a painter, which perhaps contributed to his unconventional approach and his freedom from academic constraints.

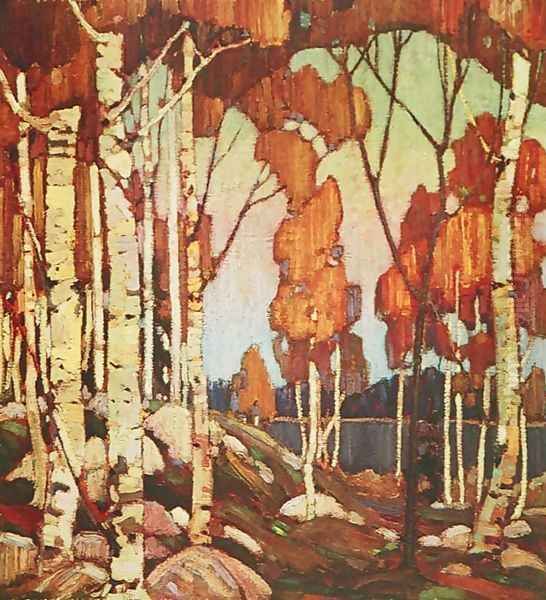

His early work shows an interest in the tonal qualities of Impressionism, focusing on light and atmosphere. However, his palette soon became much bolder and more expressive, aligning him more with Post-Impressionist painters like Vincent van Gogh, whose use of impasto and vibrant, subjective colour Thomson would have known through reproductions and exhibitions. The influence of Art Nouveau, with its emphasis on decorative patterns and sinuous lines, can be seen in the stylized treatment of trees and water in some of his compositions, particularly in his larger canvases. Scandinavian art, particularly depictions of northern landscapes, was also an interest among his circle and likely influenced his approach to capturing the stark beauty of the Canadian north.

Thomson's technique was characterized by vigorous, often thick, application of paint (impasto), creating textured surfaces that convey the ruggedness of the landscape itself. His colour sense was extraordinary; he used colour not just descriptively but emotionally, to evoke the mood and feeling of a place. He was unafraid of using strong, sometimes non-naturalistic colours to heighten the expressive impact of his work. His compositions, while seemingly spontaneous, often reveal a sophisticated underlying design sense, likely honed during his years as a commercial artist.

His development as an artist was remarkably rapid. In the short span of five years, he moved from relatively conventional landscape sketches to works of astonishing power and originality. He experimented constantly, pushing the boundaries of colour and form. His small oil sketches, in particular, are prized for their immediacy and freshness, capturing fleeting moments with an almost breathtaking intensity. Many critics and art historians consider these sketches to be among his finest achievements, perhaps even more vital than some of his larger studio canvases.

Representative Works: Icons of Canadian Art

Though his oeuvre is not vast in terms of large canvases, several of Tom Thomson's paintings have become iconic in Canadian art history.

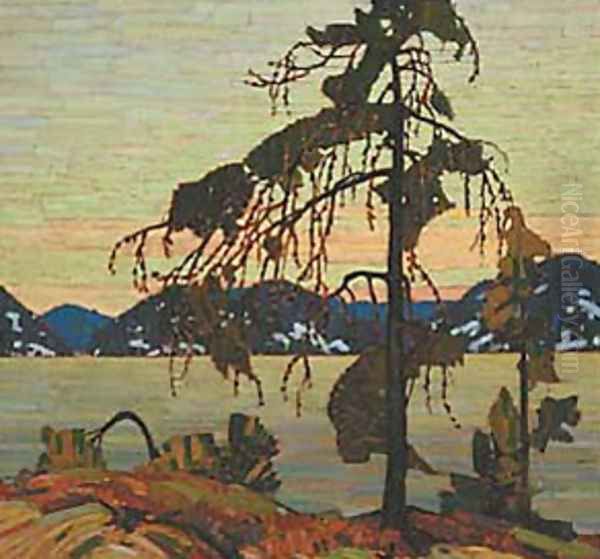

_The Jack Pine_ (1916-1917): Perhaps his most famous work, The Jack Pine depicts a solitary, windswept pine tree, silhouetted against a dramatically coloured sky and a distant, rolling landscape. The tree, a common feature of the Canadian Shield, is rendered with a stark, almost graphic quality, its branches forming a dynamic, decorative pattern. The painting has come to symbolize the resilience and rugged beauty of the Canadian wilderness and the spirit of the nation itself. Its composition shows a masterful balance of realism and stylization.

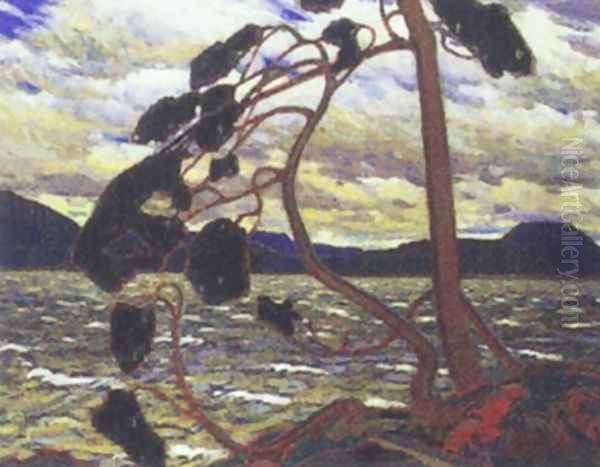

_The West Wind_ (1916-1917): Another iconic canvas, The West Wind is a companion piece to The Jack Pine and shares its powerful, stylized depiction of a windswept pine. The tree in The West Wind is even more dramatically contorted, its branches reaching across the canvas, conveying the force of the wind. The vibrant colours of the sky and water, and the dynamic composition, make this a powerful and enduring image. It is believed to be one of the last major canvases he worked on.

_Northern River_ (1914-1915): This painting showcases Thomson's ability to create a sense of immersive depth and decorative patterning. A screen of dark, slender tree trunks in the foreground frames a view of a sunlit river beyond. The interplay of light and shadow, and the rhythmic arrangement of vertical forms, create a complex and visually engaging composition. It reflects the influence of Art Nouveau in its decorative qualities.

_The Pointers_ (c. 1916-1917): This work depicts a log boom, with "pointers" (long logs used to guide floating timber) in the foreground. It’s a scene of human activity within the wilderness, yet Thomson imbues it with the same sense of grandeur and dynamic energy as his pure landscapes. The strong diagonal lines and bold colours create a sense of movement and power.

Sketches: Beyond these major canvases, Thomson produced hundreds of oil sketches that are masterpieces in their own right. Works like Autumn Foliage (1915), Sunset Sky (1915), and The Northern Lights (sketch for a larger, uncompleted painting, 1916) demonstrate his extraordinary ability to capture the ephemeral qualities of light and atmosphere with astonishing speed and accuracy. These sketches often display a freedom and experimental quality that is incredibly modern. For instance, Petawawa Gorges (1916) and Tea Lake Dam (1916) show his bold use of colour and expressive brushwork.

These works, and many others, established a new vision for Canadian landscape painting, one that was deeply rooted in direct experience of the land and expressed with a modern sensibility.

Relationship with the Group of Seven

Tom Thomson's relationship with the artists who would formally constitute the Group of Seven in 1920 is complex and crucial to understanding his impact. While he died three years before the Group's official formation, he is universally considered its spiritual predecessor and a profound influence.

As mentioned, Thomson worked closely with J. E. H. MacDonald, Arthur Lismer, Frederick Varley, and Franklin Carmichael at Grip Ltd. and later at Rous & Mann. He shared sketching trips and artistic discussions with them. Lawren Harris, A. Y. Jackson, and F. H. Varley became close associates, sharing his passion for the northern landscape. Harris and Dr. MacCallum provided crucial financial and moral support. A. Y. Jackson, in particular, became a close friend and painting companion, sharing a studio space with Thomson in the Studio Building during the winter of 1913-1914. Jackson, who had studied in Europe and was familiar with Impressionist and Post-Impressionist techniques, offered Thomson valuable technical advice and encouragement.

The future Group members recognized Thomson's unique talent and his intuitive understanding of the Canadian wilderness. His dedication to capturing its essence, often under challenging conditions, inspired them. He showed them the artistic potential of Algonquin Park and other northern regions, encouraging them to venture beyond the more pastoral landscapes that had previously dominated Canadian art. His bold use of colour and expressive brushwork provided a model for their own explorations.

When the Group of Seven held their first exhibition in 1920, they did so partly to honor Thomson's memory and to assert the vision of a national art that he had helped to forge. His paintings, such as The Jack Pine and The West Wind, were often exhibited alongside their works, underscoring his foundational role. While he was never a formal member, the Group members always acknowledged him as a kindred spirit and a pivotal figure in their movement. Artists like J. E. H. MacDonald wrote eloquently about Thomson's genius and his profound connection to nature. The Group, including later members like A. J. Casson, L. L. FitzGerald, and Edwin Holgate, continued to explore the Canadian landscape, each in their own distinct style, but all indebted to the path Thomson had blazed.

Other contemporary Canadian artists, while not part of the Group of Seven, were also part of the broader artistic milieu. Figures like Emily Carr, working on the West Coast, shared a similar passion for capturing the Canadian landscape and Indigenous culture with a modern sensibility, though her direct interaction with Thomson was minimal. Earlier Canadian landscape painters like Cornelius Krieghoff or Lucius O'Brien had depicted the Canadian scene, but Thomson and the Group of Seven brought a new, modern, and nationalistic fervour to the genre. Even international figures like the American painter Rockwell Kent, who painted stark northern landscapes, or European Post-Impressionists like Paul Gauguin or Edvard Munch, whose expressive use of colour and form resonated with the modernist spirit, provide a broader context for Thomson's achievements.

The Unsolved Mystery: Thomson's Tragic Demise

The circumstances surrounding Tom Thomson's death in July 1917 remain one of Canadian history's most enduring and debated mysteries. On July 8, 1917, Thomson set out alone in his canoe on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park. He was never seen alive again. His overturned canoe was found later that day, and his body was discovered in the lake eight days later, on July 16.

The official cause of death, as determined by a cursory examination, was accidental drowning. However, several unsettling details and conflicting accounts soon gave rise to speculation and alternative theories. His watch had stopped at 12:14. There was a four-inch bruise or wound on his right temple. Fishing line was found wrapped nineteen times around his left ankle. These facts seemed inconsistent with a simple drowning.

Over the decades, numerous theories have been proposed:

1. Accidental Drowning: This remains the official explanation. Thomson might have stood up in his canoe, perhaps to cast a fishing line or to relieve himself, lost his balance, struck his head, and fallen unconscious into the water. A sudden squall, common on Algonquin lakes, could also have capsized his canoe.

2. Suicide: Some have suggested that Thomson, known to be moody and perhaps troubled by personal issues (including a rumored romance with Winnifred Trainor, who may have been pregnant), took his own life. However, his friends and those who knew him well largely dismissed this idea, pointing to his plans for the future and his deep love of life and painting.

3. Murder: This is the most sensational and persistent theory. Motives proposed range from a dispute over money or a woman, to a drunken brawl, to an altercation with poachers or illegal fishing operators. Suspicion has fallen on various local figures, including Shannon Fraser, at whose Mowat Lodge Thomson often stayed, or Martin Blecher Jr., a neighboring cottager with whom Thomson had reportedly argued. The head wound and the tangled fishing line are often cited as evidence supporting foul play.

4. Wartime Intrigue: A more outlandish theory suggests Thomson might have been mistaken for, or involved with, German spies, given the wartime paranoia and the proximity of Algonquin Park to certain training areas. This theory has little credible evidence.

The mystery was compounded by the handling of his burial. Thomson was initially buried in the small cemetery on Canoe Lake. However, his family, particularly his older brother George Thomson (also an artist), arranged for his body to be exhumed and re-interred in the family plot in Leith, Ontario, two days later. Decades later, in 1956, when a group including some of Thomson's old friends and admirers investigated the Canoe Lake grave, they found remains. Whether these were Thomson's (suggesting the coffin sent to Leith was empty or contained someone else) or an unmarked Indigenous burial remains a point of contention, adding another layer to the legend.

Regardless of the true cause, Thomson's premature death at the age of 39, at the height of his artistic powers, was a profound loss for Canadian art. The mystery surrounding it, however, has undoubtedly contributed to his legendary status, transforming him into a near-mythical figure in Canadian culture.

Enduring Legacy and Impact on Canadian Art

Tom Thomson's impact on Canadian art is immeasurable. Despite his short career, he fundamentally changed the way Canadians saw their own country and how Canadian artists approached the landscape.

His most significant contribution was the development of a powerful and authentic visual language for depicting the Canadian wilderness. He rejected the picturesque conventions of earlier landscape painting and instead embraced the rugged, untamed character of the North. His bold use of colour, expressive brushwork, and dynamic compositions captured the vitality and spirit of the land in a way that had never been done before. He made the wilderness a subject of serious artistic exploration, revealing its beauty, its harshness, and its spiritual power.

He was a crucial catalyst for the Group of Seven. His pioneering work in Algonquin Park and his passionate dedication to a distinctly Canadian art inspired them to pursue their own explorations of the national landscape. They built upon his legacy, carrying forward his vision of an art that was rooted in Canadian experience. The Group of Seven, in turn, played a major role in shaping Canada's cultural identity in the early 20th century, and Thomson is inextricably linked to their achievements.

Thomson's work also fostered a sense of national pride and a deeper appreciation for the Canadian landscape among the broader public. His paintings became symbols of Canada, reproduced on posters, stamps, and in countless publications. They helped to define a Canadian "sense of place" and contributed to the growing cultural nationalism of the period. His art resonated with a desire for cultural independence and a recognition of the unique character of the Canadian environment.

His legacy continues to inspire contemporary artists in Canada and beyond. His approach to plein air sketching, his bold experimentation with colour and technique, and his profound connection to nature remain relevant. Major exhibitions of his work continue to draw large crowds, and his paintings are prized possessions in public and private collections, including the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa and the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario, which has a significant holding of works by Thomson and the Group of Seven.

The ongoing fascination with his life and death also contributes to his enduring presence in the Canadian imagination. Numerous books, plays, documentaries, and songs have been created about him, exploring both his artistic achievements and the mystery of his demise. He has become a romantic, almost mythical figure – the quintessential Canadian artist, deeply connected to the wilderness, whose life was cut tragically short.

Conclusion: The Unfading Light of a Northern Star

Tom Thomson's journey from a commercial artist to a visionary painter of the Canadian wilderness is a remarkable story of artistic passion and rapid development. In a few short years, he produced a body of work that not only captured the unique beauty of Algonquin Park but also helped to define a new direction for Canadian art. His vibrant colours, bold brushwork, and profound empathy for the natural world created images that have become deeply embedded in Canada's cultural consciousness.

While the mystery of his death on Canoe Lake may never be fully resolved, it adds a layer of poignant legend to his already compelling story. What remains undisputed is the power and originality of his art. He provided a new lens through which to see the Canadian landscape, revealing its wild majesty and its spiritual depth. As a precursor and inspiration to the Group of Seven, and as an artist who forged a unique and enduring vision, Tom Thomson remains a pivotal figure in Canadian art history – a northern star whose light continues to shine brightly, illuminating the path for generations of artists and art lovers. His work is a testament to the transformative power of art and the enduring allure of the wilderness.