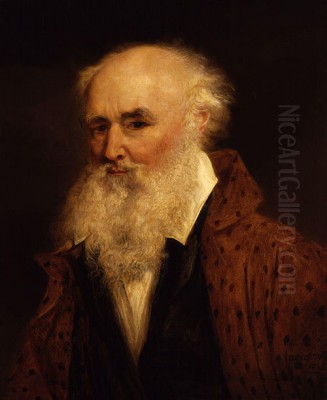

James Ward stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of British art. Spanning an exceptionally long life and career, from 1769 to 1859, he witnessed and contributed to the dramatic shifts in artistic taste from the late Georgian period through the height of Romanticism and into the early Victorian era. Primarily celebrated for his powerful animal paintings and evocative landscapes, Ward was also a highly accomplished engraver, demonstrating a versatility that marked him as a formidable talent. His work, characterised by its energy, meticulous detail, and often dramatic intensity, secured him a place within the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts and left a legacy of compelling imagery that continues to fascinate scholars and art lovers alike.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings in London

James Ward was born in Thames Street, London, on October 23, 1769. His family background was steeped in the print trade; his elder brother, William Ward (1766-1826), became a noted mezzotint engraver. This familial connection undoubtedly provided James with early exposure to the visual arts and the craft of printmaking. His formal training began under the tutelage of John Raphael Smith (1751-1812), one of the leading engravers of the day, known for his masterful mezzotints after contemporary painters like Sir Joshua Reynolds and George Romney.

During his apprenticeship with Smith, which lasted approximately seven years, Ward honed his skills in engraving, particularly mezzotint. This technique, capable of rendering rich tonal variations, would serve him well throughout his career, both as a means of reproducing his own paintings and those of others. However, Ward's ambitions extended beyond engraving. He harboured a strong desire to become a painter, a path he largely pursued through determined self-education.

The Influence of George Morland

A pivotal figure in Ward's early artistic development was George Morland (1763-1804). Morland, a popular painter of rustic genre scenes and animals, became Ward's brother-in-law when he married James's sister, Anne, in 1786. For a time, James worked closely with Morland, assisting him and inevitably absorbing aspects of his style. Morland's influence is evident in Ward's early paintings, particularly in his choice of rural subjects and his treatment of animals, which initially echoed Morland's looser, more picturesque manner.

Ward even engraved many of Morland's popular compositions, further immersing himself in his brother-in-law's artistic world. However, the association was not without its complexities. Morland's notoriously dissolute lifestyle contrasted sharply with Ward's more disciplined temperament. Furthermore, Ward grew increasingly eager to establish his own artistic identity, distinct from that of the highly successful Morland. This led him to consciously move away from Morland's style, seeking new sources of inspiration.

Some sources suggest that John Raphael Smith, observing Ward's early painting efforts, advised him to stick to engraving, believing it offered a more secure path to financial success. Whether this advice stemmed from genuine concern or professional jealousy is unclear, but Ward remained resolute in his determination to master painting. He diligently studied the works of Old Masters and sought to develop a more robust and technically sophisticated approach.

Forging an Independent Path: The Impact of Rubens

As Ward sought to define his own artistic voice, he turned towards the grander, more dynamic style of the Flemish Baroque master, Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640). The energy, rich colour, dramatic compositions, and sheer painterly vigour of Rubens resonated deeply with Ward's own artistic inclinations. This influence became increasingly apparent in Ward's work from the early 1800s onwards.

The shift is noticeable in the increased scale, ambition, and dramatic intensity of his paintings. He moved away from the charming, smaller-scale rustic scenes associated with Morland towards more powerful depictions of animals, often shown in conflict or set within imposing landscapes. The influence of Rubens is palpable in works featuring struggling, muscular forms, dynamic movement, and a heightened sense of emotional drama, far removed from the relative tranquility of Morland's world.

Ward's study of Rubens was not merely superficial imitation. He absorbed the principles of Baroque composition and applied them to his own observations of nature and animal anatomy. This fusion of influences – the detailed realism honed through observation and the dynamic energy inspired by masters like Rubens – became a hallmark of Ward's mature style. This ability to synthesise influences while maintaining a personal vision distinguished him from many contemporaries.

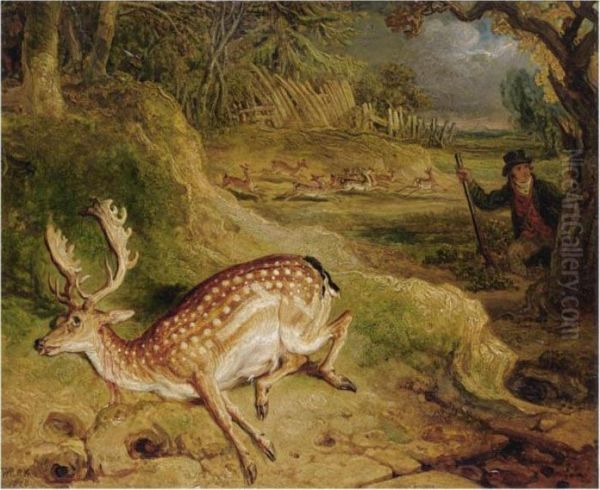

Master of Animal Painting

By the turn of the century, James Ward began to establish a formidable reputation as an animal painter. His deep understanding of animal anatomy, combined with his ability to capture their characteristic movement and spirit, set his work apart. He received a significant, though ultimately ill-fated, commission around 1800 from the Board of Agriculture, spearheaded by Lord Somerville. The ambitious project aimed for Ward to paint portraits of representative examples of various British livestock breeds.

Ward embarked on this project with enthusiasm, travelling and producing numerous studies and paintings of cattle, sheep, and horses. These works showcased his meticulous attention to detail and his ability to render the specific characteristics of different breeds with accuracy. Although the grand scheme was never fully realised due to funding issues and perhaps its sheer scale, the project significantly enhanced Ward's reputation as the pre-eminent animal painter of his day, arguably surpassing even the legacy of the great George Stubbs (1724-1806) in the eyes of some contemporaries, though Stubbs's focus was often more overtly scientific.

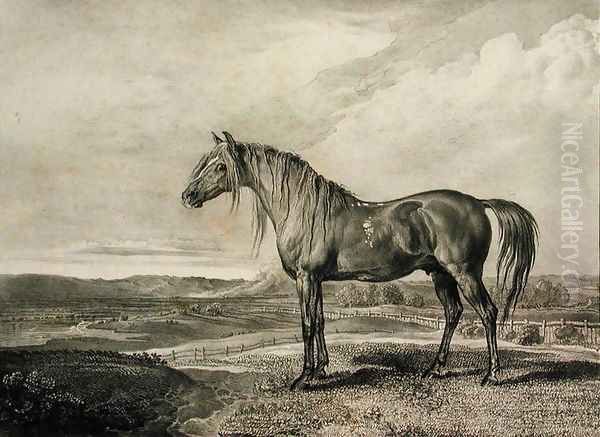

His animal portraits were not mere documentation; they were imbued with personality and vitality. A prime example is his portrait of Copenhagen (c. 1824), the Duke of Wellington's famous warhorse ridden at the Battle of Waterloo. Ward depicted the celebrated steed with noble bearing and anatomical precision, capturing the spirit of the animal that had carried the Duke through his greatest victory. He painted numerous portraits of prize-winning livestock for proud landowners, demonstrating a keen ability to satisfy patrons while maintaining artistic integrity. Other contemporaries in animal painting included Sawrey Gilpin (1733-1807), but Ward brought a unique Romantic intensity to the genre.

Confronting the Sublime: Landscape and Drama

While renowned for his animal subjects, James Ward was also a landscape painter of considerable power and originality. His approach to landscape was deeply influenced by the Romantic concept of the Sublime – the evocation of awe, terror, and overwhelming emotion in the face of nature's grandeur and power. He sought out dramatic scenery, favouring rugged mountains, turbulent skies, and wild, untamed environments.

His undisputed masterpiece in this genre is Gordale Scar (or A View of Gordale, in the Manor of East Malham in Craven, Yorkshire, the Property of Lord Ribblesdale), painted between 1812 and 1814 and exhibited in 1815. This enormous canvas, now housed in Tate Britain, depicts a towering limestone ravine in Yorkshire. Ward exaggerates the scale and drama of the scene, emphasizing the immense, craggy cliffs that dwarf the cattle sheltering beneath them. The painting is a quintessential expression of the Sublime, conveying the overwhelming power and majesty of nature.

Gordale Scar was conceived partly in response to a challenge or commission, possibly intended to rival works by landscape painters like Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg (1740-1812), known for his dramatic scenes. Ward's painting, however, possesses a unique intensity and a focus on the raw, untamed aspects of the British landscape. While contemporaries like J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) and John Constable (1776-1837) were revolutionising landscape painting in their own ways, Ward's contribution, particularly Gordale Scar, remains a powerful statement within the Romantic movement, blending topographical observation with high drama. His handling of light and atmosphere in such works is often masterful, enhancing the emotional impact.

Ambitious Allegories and Historical Subjects

Ward's artistic ambition extended to large-scale historical and allegorical subjects, although these met with more mixed success than his animal and landscape paintings. His most notable venture in this field was the Allegory of Waterloo, also known as The Triumph of the Duke of Wellington. Commissioned following a competition organised by the British Institution in 1816, Ward worked on the colossal painting for several years, finally exhibiting it in 1821.

Measuring an immense 21 by 35 feet, the painting was intended as a grand national statement celebrating the victory over Napoleon. However, its complex allegorical programme, featuring symbolic figures alongside portraits of Wellington and his staff, proved difficult for audiences and critics to decipher. While technically impressive in parts, the overall composition was considered confusing and overwrought. The painting failed to secure a buyer and ultimately proved a significant financial and critical disappointment for Ward, despite the immense effort invested.

This venture into grand history painting, a genre championed by artists like Benjamin West (1738-1820) in the previous generation, highlights Ward's ambition to compete at the highest levels of academic art. Though the Waterloo allegory was not deemed a triumph, it demonstrates his willingness to tackle complex themes on a monumental scale, pushing the boundaries of his established reputation as an animal and landscape specialist.

Continued Work as an Engraver

Throughout his career as a painter, James Ward never entirely abandoned his original craft of engraving. His skills as a mezzotint engraver remained highly regarded. In 1794, his abilities were formally recognised when he was appointed Painter and Engraver in Mezzotinto to the Prince of Wales (later King George IV). This prestigious appointment acknowledged his standing in both disciplines.

He produced numerous engravings after his own paintings, allowing his compositions to reach a wider audience. This was a common practice for artists of the period, providing an additional source of income and disseminating their work beyond the confines of exhibitions and private collections. He also continued, particularly earlier in his career, to engrave works by other artists, including his brother William Ward and, significantly, George Morland. His engravings often display the same energy and attention to texture found in his paintings.

The dual practice of painting and engraving gave Ward a comprehensive understanding of visual representation, from the broad handling of paint to the intricate tonal gradations achievable through mezzotint. This technical mastery underpinned the confidence and authority evident in his best work across both media. His engravings provide valuable records of his own compositions and those of his contemporaries.

The Royal Academy and Professional Recognition

James Ward's rising prominence was reflected in his relationship with the Royal Academy of Arts, the most important artistic institution in Britain. He began exhibiting regularly at the Academy's annual exhibitions in the 1790s. His powerful animal paintings and dramatic landscapes quickly gained attention, distinguishing him from the more conventional works often displayed.

His talent was formally recognised by his peers with his election as an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1807. This was followed by his elevation to the status of full Royal Academician (RA) in February 1811. Achieving RA status was a significant mark of distinction, confirming his place among the leading artists of the nation. It granted him voting rights within the Academy and the prestigious post-nominal letters "RA".

Ward remained a loyal contributor to the Royal Academy exhibitions for most of his long life, continuing to submit works well into his eighties. The Academy provided the primary venue for showcasing his major paintings to the public and potential patrons. His election solidified his professional standing and placed him alongside other luminaries of the time, such as the portraitist Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830) and the landscape giants Turner and Constable, though his relationship with some contemporaries could be complex, marked by professional rivalry as well as mutual respect.

Later Life, Challenges, and Legacy

Despite his status as a Royal Academician and his earlier successes, James Ward faced considerable financial difficulties in his later years. The mixed reception of ambitious projects like the Allegory of Waterloo, changing artistic tastes favouring different styles, and perhaps a degree of personal inflexibility contributed to a decline in lucrative commissions. He continued to paint prolifically, but struggled to maintain the income levels of his peak years.

He remained dedicated to his art, working with undiminished energy even in old age. His long career meant he outlived many of his early contemporaries and influences, including Morland and J.R. Smith. He continued exhibiting at the Royal Academy until 1855. His resilience is remarkable, producing a vast body of work over more than six decades.

James Ward died in Cheshunt, Hertfordshire, on November 17, 1859, just weeks after his 90th birthday. At the time of his death, his reputation had somewhat faded, overshadowed by newer trends in Victorian art. However, subsequent reappraisals, particularly in the 20th century, have re-established his importance as a key figure in British Romanticism. His works are now held in major public collections, including Tate Britain, the National Gallery, London, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Yale Center for British Art, and many others.

Artistic Style Revisited: Energy and Detail

James Ward's artistic style is characterised by a unique blend of meticulous realism and Romantic dynamism. His deep knowledge of anatomy, particularly evident in his animal paintings, provided a solid foundation for his work. He rendered fur, hide, and musculature with convincing texture and accuracy, grounding even his most dramatic scenes in careful observation. This detailed approach likely stemmed in part from his training as an engraver, which demanded precision and close attention to form and tone.

However, Ward infused this realism with the energy and emotional intensity characteristic of Romanticism. His compositions are often dynamic, featuring diagonal lines, swirling movement, and dramatic contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro). He favoured strong, rich colours, influenced perhaps by his study of Rubens, which added to the visual impact of his canvases. Whether depicting a prize bull, a wild landscape, or a fight between predators, Ward aimed to convey the inherent power and spirit of his subject.

His versatility is also notable. While best known for animals and landscapes, he also produced portraits and historical/allegorical works. His engagement with the Sublime in landscape painting, particularly in Gordale Scar, marks a significant contribution to that aspect of British Romantic art. He successfully navigated the demands of patrons seeking accurate depictions of livestock while pursuing his own vision of powerful, emotionally charged art.

Conclusion: An Enduring Romantic Vision

James Ward remains a compelling figure in British art history. His long and productive career bridged the late 18th and mid-19th centuries, encompassing the rise and peak of Romanticism. As both a painter and engraver, he demonstrated exceptional technical skill and artistic vision. His powerful animal paintings captured the vitality and specific character of his subjects with unparalleled energy, while his landscapes, especially the monumental Gordale Scar, stand as potent expressions of the Romantic Sublime.

Though influenced by artists as diverse as George Morland and Peter Paul Rubens, Ward forged a distinctive style marked by detailed realism combined with dramatic intensity and rich colour. Despite facing financial struggles later in life and a period of relative neglect after his death, his reputation has been firmly re-established. James Ward's contribution to animal painting and Romantic landscape ensures his enduring importance within the narrative of British art. His work continues to impress with its technical brilliance and its powerful evocation of the natural world's energy and grandeur.