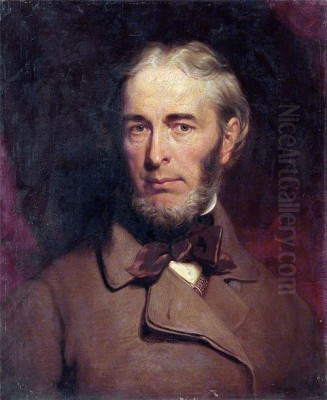

James William Giles stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the pantheon of 19th-century Scottish art. A versatile and prolific artist, he excelled in landscape painting, particularly scenes of the Scottish Highlands, sporting subjects, and animal portraiture. His dedication to his craft, his involvement in the burgeoning Scottish art institutions, and his keen eye for the natural world cemented his place in the annals of British art history.

Early Life and Nascent Talent in Aberdeen

Born on January 4, 1801, in Glasgow, Scotland, James William Giles was the son of Peter Giles, a designer of some local repute in Aberdeen, particularly known for his work with calico printing and as a "designer for manufacturers." The family's artistic inclinations likely provided an early stimulus for young James. His innate talent for drawing and painting manifested at a remarkably young age. By the tender age of 13, he was already demonstrating professional capabilities, undertaking commissions to paint the lids of snuff boxes with intricate depictions of animals and figures. This early work, though modest in scale, hinted at the meticulous detail and observational skill that would characterize his later, more ambitious canvases.

During these formative years in Aberdeen, Giles also contributed to the local art scene by teaching students at the Aberdeen Public Drawing Class. This early foray into instruction suggests a confidence in his abilities and a desire to share his burgeoning knowledge. The rugged landscapes surrounding Aberdeen and the wider Scottish Highlands became his outdoor studio, as he frequently embarked on sketching expeditions, particularly to the Dee and Don valleys, immersing himself in the scenery that would become a lifelong inspiration.

Formal Training and Broadening Horizons: London, Paris, and Italy

While largely self-taught in his initial development, James William Giles recognized the importance of formal training and exposure to the wider European art world. Around 1823 or 1824, his marriage to Clementina Farquharson, a woman of some means, provided him with the financial stability to pursue further artistic studies abroad. This union was pivotal, allowing him to travel and learn without the immediate pressure of earning a living solely through his art.

His first significant educational journey took him to London, the bustling heart of the British art world. Here, he would have encountered the works of leading British painters such as J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, whose revolutionary approaches to landscape painting were transforming the genre. He also spent time in Paris, a city then teeming with artistic innovation. It is documented that he studied under a French historical painter. While the exact identity is sometimes debated, figures like Jean-François Millet, known for his peasant scenes and Barbizon School associations, or other academic painters of the era, would have offered valuable insights into technique and composition.

Perhaps most transformative was his extended tour of Italy, a traditional pilgrimage for aspiring artists. From 1824 to 1826, Giles immersed himself in the cradle of the Renaissance and Classical antiquity. He diligently copied an impressive forty works by Old Masters, including titans like Titian, Raphael, and Correggio. This practice was a cornerstone of artistic education at the time, allowing artists to intimately understand the techniques, colour palettes, and compositional strategies of their revered predecessors. These copies, later exhibited at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford in 1970, attest to his dedication and skill in emulating diverse styles. This period undoubtedly refined his draughtsmanship and deepened his appreciation for the classical traditions of art.

A Pillar of the Scottish Art Establishment: The Royal Scottish Academy

Upon his return to Scotland, armed with new skills and a broadened artistic perspective, James William Giles quickly established himself as a leading painter. He settled primarily in Aberdeen, though he maintained connections with Edinburgh, the nation's artistic capital. His talent did not go unnoticed. Giles was instrumental in the formation of the Aberdeen Artists' Society, demonstrating his commitment to fostering a vibrant local art community.

His most significant institutional affiliation came with the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA). When the Academy was founded in 1826, initially as the Scottish Academy, Giles was among its earliest and most enthusiastic supporters. In 1829, he was elected a full Academician, one of the first twenty-six artists to receive this honour. This was a testament to his standing among his peers and his recognized contributions to Scottish art. He became a prolific exhibitor at the RSA's annual exhibitions throughout his career, showcasing a wide range of his works and consistently engaging with the Scottish art-viewing public. His dedication to the RSA was unwavering, and he played an active role in its affairs.

Beyond the RSA, Giles also sought recognition further afield. He regularly sent works to the Royal Academy in London, where he exhibited over eighty paintings, and also showed at the British Institution and the Royal Society of British Artists in Suffolk Street. This consistent presence in major London exhibitions helped to raise his profile beyond Scotland.

Artistic Style: Realism, Romance, and the Scottish Scene

James William Giles's artistic style is characterized by a blend of detailed realism, a Romantic sensibility for the grandeur of nature, and a deep affection for Scottish subjects. His landscapes, particularly those of the Highlands, are rendered with a keen eye for topographical accuracy, yet they often evoke a sense of atmosphere and the sublime. He was adept at capturing the play of light and shadow across rugged mountains, tranquil lochs, and dense forests. His work can be seen in the tradition of Scottish landscape painters like Alexander Nasmyth, often considered the "father of Scottish landscape painting," and his contemporary Horatio McCulloch, who also specialized in dramatic Highland scenery.

In his animal paintings, especially his depictions of deer, game birds, and sporting dogs, Giles displayed remarkable anatomical precision and an ability to convey the vitality of his subjects. These works resonated with the prevailing Victorian taste for sporting art, a genre popularized by English artists like Sir Edwin Landseer, whose influence was strongly felt in Scotland. Giles's fishing scenes, often set against meticulously rendered riverine landscapes, were particularly popular, capturing the thrill of the sport and the beauty of the Scottish waterways.

He was proficient in both oil and watercolour. His watercolours, often used for sketching outdoors or for more intimate compositions, demonstrate a fluid handling of the medium and a sensitivity to atmospheric effects. His oil paintings, typically larger and more finished, allowed for greater depth of colour and textural detail. While his Italian studies exposed him to classical ideals, his primary focus remained the direct observation and faithful representation of the natural world, particularly the unique character of his native Scotland. His work shows less of the overt classicism of Claude Lorrain and more of an affinity with the detailed naturalism found in some Dutch Golden Age painters like Jacob van Ruisdael, albeit translated into a distinctly Scottish idiom.

Notable Works and Diverse Commissions

Throughout his long and productive career, James William Giles created a substantial body of work. While a comprehensive catalogue is extensive, certain paintings and types of commissions stand out. "The Welsh Wife," held by the National Galleries of Scotland, is a fine example of his genre painting, showcasing his ability to capture character and narrative.

His depictions of Highland deer, such as "Stalking Deer" or "Highland Gillie with a Dead Stag," were highly sought after. These paintings not only celebrated the sport of deer stalking, which gained immense popularity in the 19th century, particularly after Queen Victoria and Prince Albert acquired Balmoral, but also showcased the majestic beauty of the red deer in its natural habitat. Similarly, his paintings of salmon fishing on rivers like the Dee or Spey were prized for their accuracy and evocative portrayal of a quintessential Scottish pastime.

Giles's talents were not confined to easel painting. He undertook various design commissions, reflecting his father's background and his own versatile skills. He is credited with designing gardens, most notably for the Earl of Aberdeen at Haddo House, demonstrating an understanding of landscape architecture. One of his most prestigious commissions was the design of a tablecloth for Queen Victoria, a mark of royal favour and recognition of his design abilities. There are also mentions of him creating a sculpture titled "Demeter," indicating an exploration into three-dimensional art, though this aspect of his career is less documented than his painting.

His portraiture, though not his primary focus, included depictions of local gentry and their prized animals. These works combined his skill in capturing a likeness with his expertise in animal painting.

Patronage, Recognition, and Later Life

James William Giles enjoyed significant patronage throughout his career. Aristocratic landowners and sporting enthusiasts were keen collectors of his work. The Earl of Kintore and the aforementioned Earl of Aberdeen were among his notable patrons. His connection with Queen Victoria, through the tablecloth commission and her general interest in Scottish art and culture, further enhanced his reputation.

His works found their way into numerous important collections. Besides the National Galleries of Scotland, his paintings are held by institutions such as the Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums (which has a significant collection reflecting his strong ties to the city), the British Museum in London, and even internationally, for instance, at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia. This widespread acquisition underscores the appeal and quality of his art.

Giles continued to paint and exhibit actively well into his later years. He remained based in Aberdeen, a city that clearly held a special place in his heart and provided constant inspiration. He passed away in Aberdeen on October 6, 1870, leaving behind a rich legacy as one of Scotland's foremost 19th-century painters. His contemporary, Sam Bough, known for his vigorous landscapes and seascapes, and Waller Hugh Paton, who specialized in detailed, often sunset-lit, Highland views, were part of the succeeding generation that built upon the foundations laid by artists like Giles.

Legacy and Context in Scottish Art

James William Giles occupies an important position in the development of Scottish art in the 19th century. He was part of a generation that sought to establish a distinctly Scottish school of painting, building on earlier traditions but also engaging with contemporary European art movements. His commitment to the Royal Scottish Academy was crucial in providing a platform for Scottish artists to exhibit and gain recognition.

His detailed and affectionate portrayals of the Scottish landscape contributed to the romantic image of Scotland that was being popularized in literature by figures like Sir Walter Scott. While artists like Rev. John Thomson of Duddingston brought a more overtly Romantic and sometimes turbulent vision to Scottish landscape, Giles offered a vision that was both majestic and grounded in careful observation.

His sporting art, particularly his deer and fishing scenes, not only catered to the tastes of his patrons but also documented aspects of Scottish rural life and tradition. He can be compared to other Scottish animal and sporting artists of the period, though he carved out his own niche with his particular focus on Highland game. Artists like William Simson and Andrew Geddes, while known for different specializations (Simson for coastal scenes and genre, Geddes for portraits), were part of the same vibrant artistic milieu in early to mid-19th century Scotland. Even the great Scottish portraitist Sir Henry Raeburn, though of an earlier generation, had set a high bar for artistic excellence in Scotland.

Modern scholarship continues to appreciate Giles for his technical skill, his dedication to Scottish themes, and his role in the nation's artistic institutions. While perhaps not as widely known internationally as some of his English contemporaries, within Scotland, his contribution is well-recognized. His work provides a valuable visual record of the Scottish landscape and sporting traditions of his time, rendered with an artist's eye and a native son's affection.

Conclusion: An Enduring Scottish Vision

James William Giles was more than just a painter of picturesque scenes; he was a chronicler of Scotland's natural beauty, a skilled animalier, and a dedicated member of its artistic community. From his early precocious talent in Aberdeen to his mature works gracing the walls of the Royal Scottish Academy and private collections, Giles consistently demonstrated a high level of craftsmanship and a deep connection to his subject matter. His legacy endures in his canvases, which continue to offer a compelling vision of 19th-century Scotland, its majestic landscapes, and its cherished sporting traditions, securing his place alongside other important Scottish artists of his era like Patrick Nasmyth and David Roberts, who, though known for different subjects, contributed to the richness of Scottish art.