Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen the Elder stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of 17th-century portraiture. Active primarily in England and later in the Netherlands, his career bridges the artistic traditions of both nations during a period of immense social, political, and cultural change. Born in London to immigrant parents, he rose to become a favoured painter of the English gentry and aristocracy, even securing royal patronage, before the turmoil of the English Civil War prompted his return to the continent. His meticulous technique, sensitive portrayal of sitters, and consistent practice of signing and dating his works provide invaluable insights into the art market and social strata of his time. This exploration delves into the life, career, artistic style, and legacy of a painter whose work reflects both the courtly elegance of Caroline England and the sober refinement of the Dutch Golden Age.

Origins and Early Life in London

Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen entered the world in London in 1593, baptized on October 14th at the Dutch Church at Austin Friars. His birth in England, however, belied his continental roots. His parents, Cornelis Jonson and Jane le Grand, were Protestant refugees, likely of Flemish or Dutch origin, who had fled the religious persecutions ravaging the Spanish Netherlands. The family's origins may trace back further to Cologne. They were part of a significant wave of migration from the Low Countries to England, particularly London, seeking refuge from the conflicts spurred by the Duke of Alva's campaigns and the broader Eighty Years' War. These émigré communities brought with them skills, trades, and cultural traditions, enriching the fabric of English society and its artistic scene.

Growing up within this immigrant community in London, likely near other Dutch and Flemish artisans and merchants, the young Cornelis would have been immersed in a milieu that valued craftsmanship and maintained strong ties to continental artistic developments. London, during the late Elizabethan and early Jacobean periods, was a burgeoning metropolis, though its native artistic tradition, particularly in painting, was arguably less developed than that found in Antwerp, Amsterdam, or Delft. Portraiture was the dominant genre, largely sustained by the patronage of the monarchy, aristocracy, and increasingly, the wealthy merchant class. Foreign-born artists often found significant success catering to this demand.

Artistic Formation and Influences

The precise details of Jonson van Ceulen's artistic training remain somewhat obscure, a common issue for artists of this period lacking extensive documentation like guild records found on the continent. It is highly probable that he received his initial training in London. However, there is speculation, supported by stylistic analysis of his early work, that he may have spent time training in the Northern Netherlands between roughly 1610 and 1618. If this journey occurred, he might have encountered the established portrait traditions of cities like Delft, perhaps absorbing influences from painters such as the highly successful Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt, known for his precise likenesses and sober realism.

Upon establishing his career in London from around 1618 onwards, Jonson's style clearly shows the impact of artists working there. An early influence appears to be Daniel Mytens the Elder, another painter of Dutch origin who was the favoured portraitist at the English court before the arrival of Van Dyck. Mytens' work, often characterized by a certain stiffness but also a detailed rendering of costume and a dignified presence, shares some affinities with Jonson's early output. Both artists excelled at capturing the textures of silks, satins, and lace, important status markers for their clientele.

However, the arrival of Anthony van Dyck in England in 1632 marked a watershed moment. Van Dyck, a former star pupil of Peter Paul Rubens, brought an unprecedented level of Baroque dynamism, elegance, and psychological depth to English portraiture. His fluid brushwork, sophisticated compositions, and ability to flatter his sitters while retaining a sense of aristocratic ease set a new standard. While Jonson never fully adopted Van Dyck's flamboyant style, the latter's influence is discernible in Jonson's later English works, particularly in a slightly looser handling of paint and more ambitious compositions, including three-quarter and full-length formats. Jonson adapted, absorbing elements of the prevailing taste while retaining his own distinct, more meticulous approach.

Establishing a Career in England

By the late 1610s, Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen was actively working as a portrait painter in London. He married Elizabeth Beke (or Beck) in 1622, and the couple had at least two children, including a son, Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen the Younger, who would also become a painter. The family resided for many years in Blackfriars, an area popular with artists and artisans, including Anthony van Dyck himself for a period. This location placed him strategically within London's artistic and social networks.

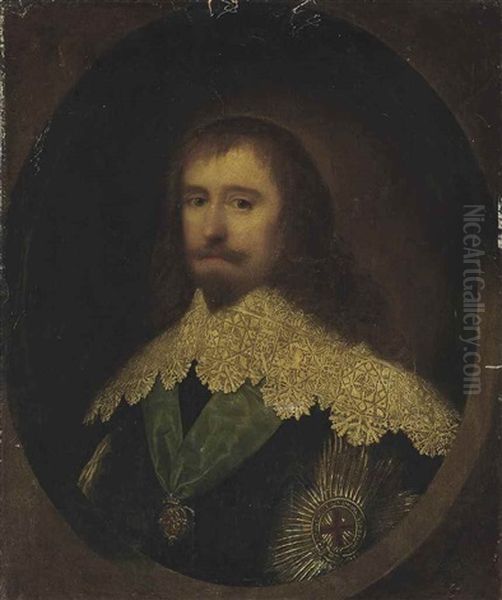

Jonson quickly found favour among the English gentry and lesser aristocracy. His style, characterized by its careful finish, honest portrayal of likeness, and exquisite attention to the details of costume and jewellery, appealed to patrons seeking dignified and accurate representations of themselves and their families. He developed a particular proficiency in the bust-length portrait, often presented within a painted oval or trompe-l'oeil stone cartouche. This format was popular and relatively affordable, allowing him to build a substantial clientele.

A notable aspect of Jonson's practice, setting him apart from many contemporaries in England at the time, was his consistent habit of signing and dating his works. This practice, more common on the continent, provides invaluable chronological markers for tracing his stylistic development and identifying his oeuvre. His signatures varied slightly over time, often appearing as "Cornelius Johnson fecit" or "C.J. fecit," followed by the year. This meticulous record-keeping aids art historians significantly and suggests a conscious professionalism in his approach.

His portraits from the 1620s and early 1630s exemplify his established English style. Works like the Portrait of Susanna Temple, later Lady Lister (c. 1620, Tate Britain) showcase his delicate modelling of features, the slightly reserved yet present psychology of the sitter, and the intricate rendering of lace collars and cuffs, which were fashionable at the time. He captured a sense of quiet dignity and social standing, avoiding excessive flattery but ensuring a refined presentation.

Royal Patronage and Peak Success

Jonson's growing reputation and skill eventually attracted attention at the highest level. In 1632, the same year Van Dyck arrived for his second, decisive stay in England, Jonson was appointed as a "servant in ordinary in the quality of picture drawer" to King Charles I. This royal appointment was a significant mark of prestige and provided him with a degree of financial security and access to elite circles. He painted portraits of the King, Queen Henrietta Maria, and other members of the royal family and court.

While Van Dyck quickly became the dominant force in royal portraiture, setting the visual tone for the Caroline court with his glamorous and influential style, Jonson continued to receive commissions. His role might be seen as complementary rather than directly competitive with Van Dyck's. Jonson's more restrained, detailed style perhaps appealed for different types of commissions or to patrons who preferred his particular aesthetic. He painted Charles I on several occasions, often in bust-length or three-quarter formats, emphasizing the King's refined features and the richness of his attire.

This period represents the apex of Jonson's success in England. He was a respected member of the London artistic community, enjoyed royal favour, and had a steady stream of commissions from the nobility and gentry across the country. His works from the 1630s show a continued refinement of his technique, sometimes incorporating more elaborate backgrounds or settings, possibly reflecting the influence of Van Dyck and the broader trends in European Baroque portraiture. He demonstrated versatility, producing miniatures as well as larger-scale works.

The Impact of the English Civil War and Emigration

The political and religious tensions that had simmered throughout Charles I's reign erupted into the English Civil War in 1642. This conflict profoundly disrupted English society, including the structures of artistic patronage. The court, the primary source of commissions for artists like Jonson and Van Dyck (who died in 1641), was fractured. Many aristocratic patrons were engaged in the conflict, displaced, or facing financial ruin. The market for luxury goods, including portraits, inevitably declined. Furthermore, the Puritanical leanings of the Parliamentarian side were generally less conducive to lavish artistic display.

Faced with this instability and the collapse of his traditional client base, Jonson made the decision to leave England. In October 1643, citing the "distractions of the Civil War," he obtained a pass to travel overseas with his family. He initially settled in Middelburg, the capital of the province of Zeeland in the Dutch Republic. Middelburg had strong existing trade and cultural links with England and Scotland, and housed a significant community of expatriates, potentially offering a familiar environment and network for the newly arrived artist.

This move marked a significant turning point in Jonson's life and career. After spending the first fifty years of his life and his entire professional career up to that point in England, he was now returning to the cultural sphere of his ancestors, albeit as an established artist shaped by his English experience. He would need to adapt his practice to the tastes and structures of the Dutch art market.

Career in the Netherlands

Jonson's transition to the Dutch Republic appears to have been relatively successful. He continued to work prolifically as a portrait painter, adapting his skills to a new clientele. After his initial period in Middelburg, he moved between other major Dutch cities, including Amsterdam and The Hague, before finally settling in Utrecht around 1652. The Dutch art market differed significantly from that of England. While there was aristocratic patronage, particularly around the House of Orange in The Hague, a large part of the demand came from wealthy burghers, merchants, civic groups, and guilds.

Jonson demonstrated his ability to cater to this market. One of his most important Dutch commissions was the group portrait The Magistrates of The Hague (1647, Museumpark, The Hague). Group portraiture was a highly prestigious genre in the Netherlands, famously practiced by artists like Frans Hals in Haarlem and, later, Rembrandt van Rijn and Bartholomeus van der Helst in Amsterdam. Jonson's handling of the Hague group portrait shows his characteristic attention to individual likenesses and fine detail, arranged in a composition that conveys the sitters' civic dignity and collective responsibility.

During his time in the Netherlands, Jonson's style subtly shifted, absorbing some aspects of contemporary Dutch portraiture while retaining his core characteristics. His Dutch portraits often maintain the meticulous finish and sensitivity seen in his English work, but perhaps with a slightly cooler palette and a greater emphasis on conveying the textures of dark fabrics favoured by the Dutch regent class. He continued to sign and date his works, leaving a clear record of his activity during this later phase of his career.

He became integrated into the local artistic communities, joining the Guild of Saint Luke in Utrecht, the professional organization for painters and other craftsmen. Utrecht was a significant artistic centre, home to artists like the "Utrecht Caravaggisti" (Gerard van Honthorst, Hendrick ter Brugghen) earlier in the century, and later figures associated with classicism like Abraham Bloemaert. While Jonson's style remained distinct, his presence in these cities placed him within the vibrant artistic discourse of the Dutch Golden Age. He interacted with and likely competed with other successful portraitists, such as Isaac Luttichuys in Amsterdam or Adriaen Hanneman in The Hague, the latter also having strong English connections. He even painted prominent figures like the Amsterdam painter Govert Flinck, himself a successful artist and former pupil of Rembrandt.

Artistic Style, Technique, and Development

Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen's artistic style is marked by consistency and a high level of technical proficiency. His primary defining characteristic is his meticulous technique. He applied paint smoothly, often on wood panels in his earlier English period, later favouring canvas. His brushwork is generally tight and controlled, allowing for the precise rendering of details, particularly in clothing, lace, jewellery, and hair. This contrasts sharply with the broader, more fluid brushwork of Van Dyck or the dynamic impasto of Rembrandt. Jonson's approach aligns more closely with the tradition of detailed realism seen in earlier Netherlandish painters like Hans Holbein the Younger (who also worked extensively in England) or contemporary Dutch fijnschilders (fine painters) like Gerrit Dou, though Jonson focused exclusively on portraiture.

His depiction of fabrics is particularly noteworthy. He excelled at capturing the sheen of silk, the density of velvet, the intricate patterns of lace, and the gleam of pearls and jewels. These elements were not merely decorative; they signified the wealth and status of his sitters, and Jonson rendered them with convincing verisimilitude. His modelling of faces is typically subtle and sensitive, achieving a good likeness without resorting to harsh lines or exaggerated features. He paid close attention to the play of light across the face, creating a sense of three-dimensionality and presence.

While often described as reserved or sober, especially when compared to the flamboyance of Van Dyck, Jonson's portraits possess a quiet psychological depth. His sitters often meet the viewer's gaze directly, but with a sense of composure and introspection rather than overt emotional display. He captured a sense of individual personality within the constraints of formal portraiture conventions. This sensitivity is evident in his portraits of men, women, and children alike.

Over his long career, his style did evolve. His earliest works from the late 1610s and early 1620s are often bust-length, tightly framed, and sometimes exhibit a slightly stiffer quality reminiscent of Jacobean portraiture. By the 1630s, influenced by the prevailing trends and perhaps Van Dyck, his compositions became more varied, incorporating three-quarter and occasionally full-length formats. He introduced more background elements, such as drapery, architectural details, or glimpses of landscape, adding depth and context to the portraits. His handling of paint may have loosened slightly during this period, though it never reached the freedom of Van Dyck.

After his move to the Netherlands, his style continued to adapt. While retaining his characteristic precision, his Dutch portraits sometimes reflect the darker palettes and more austere presentation favoured in Dutch civic portraiture. The commission for group portraits also required him to develop compositional strategies for arranging multiple figures convincingly within a single frame. Throughout his career, however, the core elements of careful execution, detailed rendering, and sensitive characterization remained constant hallmarks of his work.

Representative Works

Jonson's extensive oeuvre provides many examples that illustrate his style and clientele.

Portrait of Susanna Temple, later Lady Lister (c. 1620, Tate Britain): An excellent example of his early English style. The bust-length format within a painted oval, the exquisite rendering of the elaborate lace collar and cuffs, and the sitter's direct yet composed gaze are characteristic. It showcases his appeal to the English gentry.

Portrait of Sir Alexander Temple (1620s, various versions): Jonson painted several members of the Temple family. Portraits of Sir Alexander often depict him in armour, a common convention for portraying gentlemen, rendered with Jonson's typical attention to the metallic sheen and intricate details.

Portrait of Thomas Coventry, 1st Baron Coventry (c. 1625-1628, National Portrait Gallery, London): Depicting the Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, this work shows Jonson operating at a high level of patronage even before his official royal appointment. The portrait conveys the sitter's authority and intelligence through a focused composition and detailed rendering of his official robes.

Portrait of an Unknown Lady (1629, Tate Britain): This work exemplifies his skill in capturing female portraiture during his peak English period. The sitter's elaborate costume, including a feathered hat and intricate lace, is rendered with precision, while her expression holds a quiet allure. The use of the painted oval frame is again present.

Portrait of King Charles I (c. 1630s, various versions, e.g., Royal Collection Trust): Jonson painted the King multiple times. These portraits, often bust-length or three-quarter length, present a dignified and recognizable image of the monarch, emphasizing the richness of his attire and the symbols of his office, though perhaps lacking the effortless grace Van Dyck imparted.

The Capel Family (c. 1640, National Portrait Gallery, London): One of Jonson's most ambitious English works, this large group portrait depicts Arthur Capel, 1st Baron Capel of Hadham, with his wife Elizabeth and their children. It showcases his ability to handle complex compositions involving multiple figures and demonstrates the influence of Van Dyckian group portraiture, although with Jonson's characteristically more detailed finish.

The Magistrates of The Hague (1647, Museumpark, The Hague): A key work from his Dutch period. This civic group portrait demonstrates his successful adaptation to the Dutch market. He carefully delineates each magistrate, giving them individual presence while uniting them in a formal composition that speaks to their collective governance.

Self-Portrait (various versions, e.g., c. 1644, National Portrait Gallery, London): Jonson painted several self-portraits throughout his career. These offer insights into how the artist saw himself, often presenting a serious, professional demeanor, consistent with the dignified portrayal of his clients.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Jonson van Ceulen's career unfolded amidst a rich and dynamic artistic landscape in both England and the Netherlands. Understanding his relationship with contemporaries helps to situate his contribution.

In England, his early career coincided with the final years of the Jacobean era, where portraiture was dominated by figures like Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger and Daniel Mytens. Jonson's more refined technique and sensitive characterization offered a fresh alternative. The arrival of Van Dyck in 1632 fundamentally changed the scene, introducing a continental Baroque flair that quickly became the benchmark for courtly elegance. While Jonson adapted, he maintained his distinct style. Other portraitists active in England during his time included George Geldorp and, emerging during the Civil War period, the talented native English painter William Dobson, whose robust style offered a stark contrast to Van Dyck's elegance. After the Restoration in 1660, Peter Lely (originally Pieter van der Faes from Soest, Westphalia), who had arrived in England around the time Jonson left, would come to dominate English portraiture with a style heavily indebted to Van Dyck.

In the Netherlands, Jonson entered one of the most vibrant art markets in history. The Dutch Golden Age saw an explosion of artistic production across various genres. In portraiture, he would have been aware of the towering figures of Rembrandt in Amsterdam and Frans Hals in Haarlem, both known for their innovative techniques and profound psychological insights, though their styles differed greatly from Jonson's meticulous approach. Amsterdam also boasted Bartholomeus van der Helst, whose smooth finish and skill in large group portraits made him immensely popular, perhaps offering a closer stylistic parallel to Jonson in some respects. In The Hague, Adriaen Hanneman was a prominent portraitist, also influenced by Van Dyck and with strong English connections. Utrecht had its own traditions, from the Caravaggisti like Honthorst to the classicism of Bloemaert. Jonson navigated this complex scene, finding his niche among patrons who appreciated his careful execution and dignified representations.

His position was unique: an artist of continental heritage, born and primarily trained (or at least professionally formed) in England, who achieved success at the English court, and then successfully transplanted his career back to the Netherlands. He acted as a conduit, embodying the cross-currents between the two artistic cultures.

Legacy and Art Historical Assessment

Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen occupies a respectable but perhaps secondary position in the grand narrative of art history. He is often overshadowed by the towering genius of contemporaries like Van Dyck in England and Rembrandt or Hals in the Netherlands. His meticulous, somewhat conservative style, while highly skilled, lacked the innovative flair or dramatic power that often attracts greater art historical attention. Consequently, he has sometimes been labelled as a competent but unexciting painter, or even relegated to the status of a "forgotten master."

However, this assessment overlooks his significant contributions. For over two decades, he was one of the leading portraitists in England, meticulously documenting the faces and fashions of the Jacobean and Caroline gentry and aristocracy. His consistent practice of signing and dating his works provides an invaluable framework for understanding English portraiture of the period. His appointment as a royal painter underscores the esteem in which he was held. His works remain crucial visual records of the individuals who shaped English society before the Civil War.

His successful transition to the Dutch art market in later life demonstrates his adaptability and the enduring appeal of his careful, sensitive style. He proved capable of competing in the demanding Dutch environment and securing important commissions, such as the Hague group portrait. His career trajectory itself is historically significant, reflecting the mobility of artists and the impact of political upheaval on artistic production in the 17th century.

His son, Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen the Younger (1634–1715), followed in his father's footsteps, working as a portrait painter in Utrecht. Today, Jonson the Elder's works are held in major public collections across the UK, including the National Portrait Gallery, Tate Britain, the Royal Collection Trust, and numerous regional museums, as well as in the Netherlands (Rijksmuseum, Mauritshuis) and other international institutions. While perhaps not a revolutionary innovator, he was a highly skilled, reliable, and sensitive painter whose oeuvre provides a rich and detailed window onto the elite societies of both England and the Netherlands in the mid-17th century. He remains an important figure for understanding the cross-cultural artistic exchanges of the period and the specific development of portraiture in England before and during the transformative era of Van Dyck.

Conclusion

Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen the Elder navigated a complex path through a tumultuous century. Born an immigrant in London, he rose to prominence through technical skill and sensitivity, capturing the likenesses of the English elite and royalty. Forced by war to return to his ancestral lands, he successfully adapted his art to the thriving Dutch market. His meticulous style, characterized by detailed rendering and quiet dignity, offers a valuable counterpoint to the more flamboyant Baroque masters of his time. While perhaps lacking the transformative impact of a Van Dyck or a Rembrandt, Jonson's consistent quality, his role as a bridge between English and Dutch artistic traditions, and his extensive, well-documented oeuvre secure his place as a significant and historically important portrait painter of the 17th century. His works continue to offer invaluable insights into the people, fashions, and social structures of the worlds he inhabited.