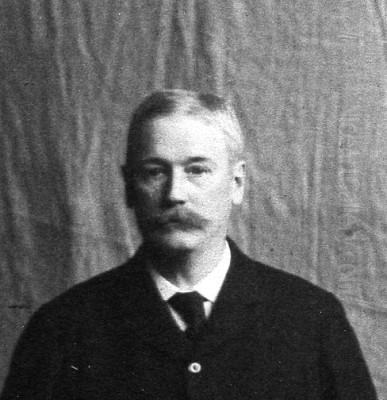

Thomas Wilmer Dewing (1851-1938) stands as a pivotal figure in American art at the turn of the 20th century, renowned for his ethereal depictions of aristocratic women in subtly rendered, atmospheric interiors and landscapes. A leading exponent of Tonalism and a key member of the Ten American Painters, Dewing crafted a unique visual language that prioritized mood, suggestion, and refined beauty over explicit narrative. His work, deeply influenced by the Aesthetic Movement and the art of James McNeill Whistler, offers a contemplative window into the Gilded Age, capturing a world of quiet leisure, intellectual pursuits, and introspective grace.

A Life Dedicated to Art: The Biography of Thomas Wilmer Dewing

Thomas Wilmer Dewing was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on May 4, 1851. His early artistic inclinations led him to initial studies in his home city, though specific details of his earliest training are somewhat scarce. It is known, however, that he worked as a lithographic apprentice in his youth, an experience that likely honed his drafting skills and attention to detail. Like many ambitious American artists of his generation, Dewing recognized the necessity of European training to refine his talents and gain credibility in the art world.

In 1876, at the age of 25, Dewing embarked for Paris, the undisputed center of the art world at the time. He enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, a popular alternative to the more rigid École des Beaux-Arts. There, he studied under influential academic painters Gustave Boulanger and Jules Joseph Lefebvre. These masters instilled in him a strong foundation in figure drawing and traditional compositional techniques, elements that would remain discernible even as his personal style evolved towards a more poetic and less overtly academic mode of expression. His time in Paris, spanning until 1879, exposed him to a myriad of artistic currents, including the burgeoning Impressionist movement, though his own path would diverge significantly.

Upon his return to the United States, Dewing initially settled in Boston before moving to New York City in 1880, which was rapidly becoming the nation's artistic hub. In 1881, he married Maria Richards Oakey (1845-1927), an accomplished painter in her own right, known for her vibrant floral still lifes and garden scenes. Maria Oakey Dewing became not only his life partner but also an intellectual and artistic companion, whose own career, though sometimes overshadowed by his, contributed to the rich artistic milieu they inhabited.

Dewing quickly established himself in the New York art scene. He began teaching at the Art Students League of New York in 1881, a position he held until 1888. His work gained recognition, and he was elected an associate member of the National Academy of Design in 1887, becoming a full Academician the following year. However, Dewing, along with a group of like-minded artists, grew dissatisfied with the conservative exhibition policies of established institutions like the National Academy and the Society of American Artists.

This dissatisfaction culminated in 1897 with the formation of the "Ten American Painters" (often referred to as The Ten). This group, which included Childe Hassam, J. Alden Weir, and John Henry Twachtman, seceded from the Society of American Artists to exhibit their work independently, seeking greater control over the presentation and promotion of their art. Dewing was a founding member and remained committed to The Ten throughout its existence, exhibiting regularly with the group until it disbanded around 1919.

A significant aspect of Dewing's career was his relationship with prominent art patrons, most notably Charles Lang Freer and John Gellatly. Freer, in particular, became a devoted collector of Dewing's work, acquiring numerous paintings that now form a cornerstone of the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Freer was drawn to the spiritual and aesthetic qualities of Dewing's art, seeing connections between his delicate Tonalism and the Asian art he also passionately collected.

From the 1890s, Dewing and his wife spent their summers at the Cornish Art Colony in Cornish, New Hampshire. This idyllic rural retreat, centered around the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, attracted a vibrant community of artists, writers, and intellectuals. The serene landscapes of Cornish often found their way into Dewing's paintings, providing a backdrop for his contemplative figures.

After a long and distinguished career, Thomas Wilmer Dewing's productivity declined in his later years. He largely stopped painting by the 1920s, though he continued to live a relatively private life. He passed away in New York City on November 5, 1938, at the age of 87, leaving behind a legacy as one of America's most distinctive and poetic painters.

The Dewing Aesthetic: Style, Mood, and Masterpieces

Thomas Wilmer Dewing's artistic style is most closely associated with Tonalism, an American art movement that emerged in the 1880s and flourished into the early 20th century. Tonalism, characterized by its soft, diffused light, muted color palettes, and emphasis on mood and atmosphere, sought to evoke subjective emotional responses rather than depict objective reality. Dewing was a master of this approach, creating paintings that are often described as dreamlike, melancholic, and deeply introspective.

His work also aligns with the broader tenets of the Aesthetic Movement, which prioritized "art for art's sake." This philosophy emphasized beauty, harmony, and decorative qualities, often drawing inspiration from diverse sources, including Japanese art and the work of James McNeill Whistler. Whistler's influence on Dewing is undeniable, particularly in the subtle gradations of tone, the flattened perspectives, and the overall pursuit of elegance and refinement. The influence of Japanese prints can be seen in Dewing's asymmetrical compositions, his use of empty space, and the delicate linearity of his figures.

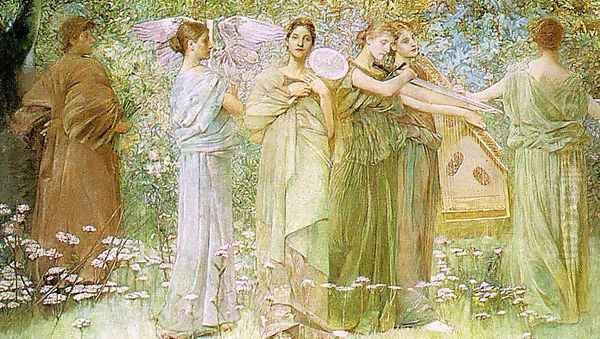

Dewing's primary subject matter was the idealized female figure, typically depicted in sparsely furnished, elegant interiors or hazy, indeterminate landscapes. These women, often tall, slender, and aristocratic in bearing, are usually engaged in quiet, leisurely activities such as reading, writing, playing musical instruments, or simply lost in thought. They are rarely portrayed interacting directly with the viewer; instead, they inhabit their own self-contained worlds, contributing to the paintings' sense of remoteness and introspection. This recurring figure became so characteristic of his work that it was sometimes referred to as the "Dewing Girl."

His color palette was typically restricted, favoring subtle harmonies of greens, grays, blues, mauves, and creams. He applied paint in thin, delicate layers, often scumbling and glazing to achieve a soft, veiled effect that blurred outlines and enhanced the atmospheric quality of his scenes. This technique contributed to the ethereal, almost ghostly presence of his figures and their surroundings.

Representative Works:

Several paintings stand out as quintessential examples of Dewing's artistic vision. The Days (1884-1886), now in the Wadsworth Atheneum, is an allegorical work depicting a procession of classically draped female figures, inspired by a poem by Ralph Waldo Emerson. It showcases his early engagement with symbolic themes and his skill in rendering the human form with grace and fluidity.

Lady in Yellow (c. 1888, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum) exemplifies his elegant portraiture and his ability to capture a sense of quiet contemplation. The subject, dressed in a striking yellow gown, is set against a subtly modulated background, her gaze averted, creating an air of mystery.

After Sunset (1892, Freer Gallery of Art) is a classic example of Dewing's Tonalist landscapes. Two women are depicted in a twilight setting, the forms dissolving into the soft, hazy atmosphere. The painting evokes a profound sense of tranquility and the fleeting beauty of the natural world.

Summer (c. 1890, Smithsonian American Art Museum) features a solitary woman in a light dress, seated in a verdant, dreamlike landscape. The high horizon line and the figure's placement create a composition that is both intimate and expansive, emphasizing her connection to the natural, yet subtly abstracted, environment.

The Spinet (c. 1902, Smithsonian American Art Museum) and Lady with a Lute (1886, National Gallery of Art) highlight Dewing's interest in musical themes. In these works, the figures are absorbed in their music-making, the instruments themselves serving as elegant props that contribute to the overall aesthetic harmony of the composition. The act of playing music becomes a metaphor for artistic creation and refined sensibility.

The Recitation (1891, Detroit Institute of Arts) and A Reading (1897, Smithsonian American Art Museum) depict women engaged in intellectual pursuits, reinforcing the image of the cultured, sophisticated female that Dewing favored. These scenes are characterized by their quietude and the subtle interplay of light and shadow in refined interior settings.

The White Dress (c. 1901, location varies/private collections) is a title he used for several compositions, all featuring women in elegant white gowns, often in sparse interiors. These works are studies in subtle tonal variations and the expressive potential of a limited palette, emphasizing purity and grace.

The Hermit Thrush (c. 1900, Smithsonian American Art Museum), another iconic Tonalist landscape, features ethereal female figures in a misty, dream-like setting, evoking a sense of poetic reverie and connection with nature.

Dewing's compositions were carefully considered, often employing a delicate balance of forms and voids. Figures are frequently shown in profile or with their backs partially turned, enhancing the sense of privacy and introspection. The backgrounds, whether interiors or landscapes, are typically simplified and abstracted, serving as atmospheric envelopes for the figures rather than detailed settings. This approach allowed Dewing to focus on the emotional and aesthetic impact of the scene, creating paintings that are more akin to visual poems than narrative illustrations.

A Circle of Influence: Dewing and His Contemporaries

Thomas Wilmer Dewing did not create his art in a vacuum. He was an active participant in the American art world of his time, and his interactions with fellow artists, architects, and patrons significantly shaped his career and artistic development.

The most formal of these associations was his membership in the Ten American Painters. This group, formed in 1897, represented a significant moment of artistic independence. Alongside Dewing, its founding members included Childe Hassam, J. Alden Weir, John Henry Twachtman, Robert Reid, Willard Metcalf, Frank Weston Benson, Edmund C. Tarbell, Joseph DeCamp, and Edward Simmons. Later, William Merritt Chase would join after Twachtman's death. These artists, while stylistically diverse (ranging from Impressionism to Tonalism), shared a desire for smaller, more thoughtfully curated exhibitions than those offered by the larger, juried shows of the Society of American Artists, from which they seceded. Dewing's Tonalist aesthetic provided a distinct voice within The Ten, complementing the more Impressionistic styles of artists like Hassam and Benson.

A paramount influence on Dewing's artistic philosophy and style was James McNeill Whistler. Dewing deeply admired Whistler's commitment to "art for art's sake," his emphasis on subtle color harmonies, and his decorative approach to composition. Whistler's "Nocturnes" and his portraits of elegant women in refined settings find echoes in Dewing's own work. Though it's unclear how much direct personal interaction they had, Whistler's aesthetic theories and artistic output were widely known and profoundly impacted Dewing's generation.

Within the Tonalist movement, Dewing shared a close friendship and artistic kinship with Dwight William Tryon. Both artists were known for their evocative, atmospheric landscapes and were favored by the collector Charles Lang Freer. Tryon and Dewing were also key figures in the Cornish Art Colony in New Hampshire, where they spent many productive summers. Their shared aesthetic sensibilities fostered a supportive artistic environment.

The Cornish Art Colony itself was a hub of creativity, centered around the renowned sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Dewing and his wife, Maria Oakey Dewing, were integral members of this community. Maria, an accomplished artist specializing in flower paintings and garden scenes, often complemented Thomas's figurative work. Her vibrant depictions of flowers sometimes appeared in the backgrounds or as decorative elements in his paintings, and her knowledge of botany informed the garden settings they cultivated in Cornish. The colony provided a stimulating atmosphere where artists, writers, and musicians exchanged ideas and found inspiration in the rural landscape.

Another crucial figure in Dewing's circle was the architect Stanford White. White, a partner in the influential firm McKim, Mead & White, was a leading proponent of the American Renaissance and a close friend to many artists. He designed frames for Dewing's paintings, viewing the frame as an integral part of the overall aesthetic presentation, a concept shared by Whistler. White also designed Dewing's studio in New York, further cementing their collaborative relationship. These custom-designed frames enhanced the precious, jewel-like quality of Dewing's canvases.

Other notable contemporaries included Kenyon Cox and Abbott Handerson Thayer, both of whom, like Dewing, were figures associated with the academic tradition but also explored idealized representations of the female form. Thayer, in particular, painted ethereal women and allegorical figures that, while different in handling, shared a certain spiritual aspiration with Dewing's work. George de Forest Brush was another contemporary known for his depictions of Native Americans and later, Renaissance-inspired mother and child portraits.

While stylistically distinct, Dewing also operated in the same Gilded Age art world as titans like John Singer Sargent. Though Sargent's bravura brushwork and society portraits contrasted with Dewing's quiet introspection, they represented different facets of the era's artistic production and patronage. The patrons who commissioned Sargent were often from the same wealthy elite who appreciated Dewing's more subtle and refined aesthetic.

These interactions, whether through formal groups like The Ten, informal communities like the Cornish Art Colony, or professional collaborations with figures like Stanford White, created a rich tapestry of influence and support that was vital to Dewing's artistic journey.

Glimpses of the Man: Anecdotes and Character

Thomas Wilmer Dewing was known for his somewhat reserved, even aloof, personality. He cultivated an image of an aesthete, deeply committed to his artistic ideals, and could be perceived as elitist by some. His dedication to beauty was paramount, and he was not one to compromise his vision for popular appeal. This intensity, however, was coupled with a meticulous and painstaking approach to his work.

One anecdote that speaks to his working method involves his extreme patience and precision. He was known to spend considerable time arranging his compositions, adjusting the pose of a model, the fall of a drapery, or the placement of an object by mere fractions of an inch until the desired harmony was achieved. His application of paint was equally deliberate, building up surfaces with thin, almost translucent layers to achieve his signature atmospheric effects. This was not the work of spontaneous inspiration but of careful, sustained effort.

His relationship with his primary patron, Charles Lang Freer, was particularly significant. Freer was more than just a buyer of art; he was a kindred spirit who deeply understood and appreciated the subtle, spiritual qualities Dewing sought to imbue in his paintings. Freer saw in Dewing's work a connection to the Asian art he also collected, particularly in its emphasis on suggestion, refinement, and the creation of a contemplative mood. Their correspondence reveals a shared aesthetic philosophy. Freer's unwavering support provided Dewing with financial security and the freedom to pursue his unique artistic vision without undue commercial pressure.

Life in the Cornish Art Colony provided a different facet of Dewing's social interactions. While he maintained his characteristic reserve, he participated in the colony's activities, which included theatricals, musicales, and outdoor pursuits. The colony was known for its blend of serious artistic endeavor and lively social life. Dewing, often seen in his distinctive attire, was a recognizable figure in this bohemian yet sophisticated rural enclave. It was said that the ethereal landscapes in many of his paintings were directly inspired by the misty mornings and twilight hours he experienced in the New Hampshire countryside.

Dewing held strong opinions about art and beauty, often expressing a preference for the refined and the aristocratic. He was critical of art that he felt was vulgar or overly sentimental. His ideal woman, as depicted in his paintings, was not the robust "Gibson Girl" popular at the time, but a more delicate, introspective figure, embodying an inner life of culture and sensitivity. This preference extended to his choice of models, whom he selected for their slender grace and ability to convey the quietude he sought.

The collaboration with Stanford White on picture frames is another interesting aspect of Dewing's artistic practice. Dewing, like Whistler, believed that the frame was an essential extension of the painting, contributing to its overall aesthetic impact. White designed elaborate, often architecturally inspired frames for Dewing's works, which were typically gilded and sometimes featured intricate carvings. These frames underscored the preciousness of the paintings and reinforced their status as objects of beauty, intended for sophisticated collectors.

There's a story, perhaps apocryphal but illustrative, that Dewing once kept a model posing for an exceptionally long period, focused intently on capturing a particular nuance of light or expression. When the session finally ended, the exhausted model remarked on the difficulty, to which Dewing, absorbed in his work, seemed almost surprised, as if the passage of time and human discomfort were secondary to the artistic pursuit. This highlights his intense concentration and perhaps a certain detachment when immersed in his creative process.

These glimpses suggest a complex individual: a dedicated and meticulous artist, a man of refined tastes and strong convictions, who carved out a unique niche in the American art world through his unwavering pursuit of a singular aesthetic vision.

Lines of Descent: Dewing's Teachers and Students

Thomas Wilmer Dewing's artistic lineage can be traced back to his formative years in Paris, and his own influence extended through his teaching career, though perhaps more subtly than that of some of his more overtly pedagogical contemporaries.

Teachers:

Dewing's most significant academic training occurred at the Académie Julian in Paris, from 1876 to 1879. This renowned private art school was a popular destination for American and international students seeking an alternative to the more restrictive École des Beaux-Arts. At the Académie Julian, Dewing studied under two prominent figures of French academic art:

Gustave Clarence Rodolphe Boulanger (1824-1888): Boulanger was a respected painter known for his historical and Orientalist subjects. He emphasized strong draftsmanship, anatomical accuracy, and well-ordered compositions – hallmarks of the academic tradition. His instruction would have provided Dewing with a solid technical foundation.

Jules Joseph Lefebvre (1836-1911): Lefebvre was another highly regarded academic painter, particularly celebrated for his idealized female nudes and portraits. He was a master of graceful lines and smooth, polished surfaces. Lefebvre's influence can be seen in Dewing's own elegant rendering of the female form, though Dewing would later develop a much softer, more atmospheric technique.

The training under Boulanger and Lefebvre instilled in Dewing the discipline and technical skills of the French academic system. While his mature style would evolve significantly towards Tonalism and Aestheticism, this rigorous early education provided the underlying structure and refinement that characterized his work. Before Paris, his studies in Boston were less formalized, and specific influential teachers from that period are not as prominently documented as his Parisian masters.

Students and Influence as a Teacher:

Upon his return to the United States, Dewing took up a teaching position at the Art Students League of New York, where he taught from 1881 to 1888. The Art Students League was a progressive institution, founded by students who had seceded from the National Academy of Design's school, seeking more liberal instruction.

It is more challenging to compile a definitive list of Dewing's students who went on to achieve significant fame and directly attributed their style to his tutelage. Dewing's own artistic persona was somewhat introverted and his style highly personal, perhaps less easily translatable into a teachable method compared to, for example, the dynamic Impressionism of William Merritt Chase, who was a famously influential teacher.

However, Dewing's presence at the League during a formative period for many young artists undoubtedly contributed to the artistic climate. He would have imparted the principles of good draftsmanship and composition learned in Paris, but likely also shared his evolving aesthetic sensibilities, which emphasized mood, subtlety, and refinement. His students would have been exposed to his preference for Whistlerian elegance and the emerging Tonalist aesthetic.

Some sources suggest that figures like Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, who later became a prominent sculptor and founder of the Whitney Museum of American Art, may have studied painting with various instructors, potentially including those at the League during periods when Dewing taught, though her primary focus shifted. The impact of a teacher like Dewing might not always manifest in direct stylistic imitation but rather in fostering an appreciation for certain artistic qualities.

His influence as a teacher was perhaps more broadly felt in his contribution to the rise of Aestheticism and Tonalism in America. By championing an art of suggestion and beauty, he offered an alternative to both strict academic realism and the more literal aspects of early American Impressionism. His work, widely exhibited and discussed, served as an example for younger artists seeking a more poetic and introspective mode of expression.

Furthermore, his role as a founding member of The Ten American Painters demonstrated a commitment to artistic independence and the pursuit of individual vision, an important lesson for any aspiring artist. While he may not have cultivated a large "school" of direct followers in the way some other artists did, Thomas Wilmer Dewing's dedication to his unique aesthetic and his years as an instructor at a key American art institution certainly left a mark on the generation of artists who came of age during his tenure. His wife, Maria Oakey Dewing, also taught and influenced students, particularly in the realm of flower painting.

The Market for Elegance: Auction Records and Market Value

The market value of Thomas Wilmer Dewing's work has experienced a trajectory common to many artists of his era, marked by initial acclaim, a period of relative obscurity, and a significant revival of interest in more recent decades.

During his lifetime, Dewing enjoyed considerable success and commanded respectable prices for his paintings. His work appealed to a select group of sophisticated collectors who appreciated his refined aesthetic and the poetic quality of his art. Chief among these was Charles Lang Freer, whose extensive acquisitions not only provided Dewing with financial stability but also ensured that a significant body of his best work would be preserved in a major public collection (the Freer Gallery of Art, part of the Smithsonian Institution). Other prominent Gilded Age collectors, such as John Gellatly (whose collection also went to the Smithsonian), were also keen admirers. This dedicated patronage meant that many of his finest pieces entered museum collections early on, which can limit the number of top-tier works appearing on the open market today.

With the rise of Modernism in the early to mid-20th century, the taste for academic art, Aestheticism, and Tonalism waned considerably. Artists like Dewing, who represented an older, more genteel tradition, fell out of favor with critics and collectors who were increasingly drawn to avant-garde movements. Consequently, the market value of his work, like that of many of his contemporaries such as Dwight William Tryon or John Henry Twachtman (in his Tonalist phases), experienced a decline. For several decades, his paintings were primarily of interest to a niche group of connoisseurs and regional museums.

The late 20th century, particularly from the 1970s onwards, witnessed a significant scholarly and curatorial reassessment of American art from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. There was a resurgence of interest in movements like American Impressionism and Tonalism, and artists like Dewing began to be re-evaluated and appreciated for their unique contributions. Exhibitions and publications dedicated to this period brought his work to a new generation of collectors and art enthusiasts.

This revival has translated into a strengthening of Dewing's auction records and market value. His paintings now regularly appear at major auction houses such as Sotheby's and Christie's. The most sought-after works are his classic depictions of elegant women in atmospheric interiors or landscapes – the quintessential "Dewing Girl." These pieces, particularly those with strong provenance, good condition, and appealing subject matter, can command prices ranging from the high tens of thousands into the hundreds of thousands of dollars, and occasionally, for exceptional examples, can reach into the low millions.

Several factors influence the market value of a Dewing painting:

Subject Matter: His iconic female figures are generally more prized than pure landscapes or lesser studies.

Quality and Condition: Well-preserved paintings that showcase his signature delicate brushwork and atmospheric effects are highly valued.

Provenance: Works that were once part of notable collections (like Freer's, though these are mostly in museums) or have a clear exhibition history tend to attract more interest.

Size and Complexity: Larger, more complex compositions often achieve higher prices, though even his smaller, jewel-like panels are appreciated.

Period: Works from his mature period, when his Tonalist style was fully developed (roughly 1890s to early 1900s), are particularly desirable.

Pastels and silverpoint drawings by Dewing also appear on the market and are valued for their delicacy and draftsmanship, though they typically command lower prices than his major oils.

While Dewing's market may not reach the stratospheric levels of some of the leading French Impressionists or later Modern masters, he holds a solid and respected position within the American art market. The enduring appeal of his refined aesthetic, his mastery of mood, and his unique vision of feminine grace ensure a continued demand for his work among discerning collectors of American art. The scarcity of his top works outside museum collections further contributes to their value when they do become available.

Enduring Whispers: Dewing's Influence on Later Art

Thomas Wilmer Dewing's influence on subsequent generations of artists is perhaps more subtle and diffused than that of more overtly revolutionary figures, yet his contribution to the tapestry of American art remains significant and his legacy continues to resonate.

His most direct impact was his role as a leading practitioner and proponent of Tonalism. Alongside artists like George Inness (in his later phase), Dwight William Tryon, and James McNeill Whistler (whose influence was transatlantic), Dewing helped establish Tonalism as a distinct and important American art movement. By prioritizing mood, atmosphere, and subjective emotional response over literal depiction, Tonalism offered a poetic alternative to both academic realism and the brighter palette of Impressionism. Dewing's particular brand of Tonalism, with its focus on refined female figures in ethereal settings, carved out a unique niche that continues to be studied and admired.

Dewing was also a key figure in the Aesthetic Movement in America. This movement, which championed "art for art's sake," emphasized beauty, harmony, and the decorative arts. Dewing's meticulously crafted paintings, often complemented by custom-designed frames by Stanford White, were conceived as complete aesthetic objects. His dedication to creating an art of quiet contemplation and refined sensibility embodied the ideals of Aestheticism, influencing a generation of artists and collectors who sought beauty and escape from the increasing industrialization and materialism of the Gilded Age.

His depiction of women, while reflecting the idealized notions of femininity prevalent in his era, also contributed to a particular iconographic tradition in American art. The "Dewing Girl" – elegant, introspective, and often engaged in intellectual or artistic pursuits – became a recognizable type. While later feminist critiques might examine the passive or decorative aspects of these portrayals, within their historical context, they represented an ideal of cultured grace and inner life that appealed to the sensibilities of his time and offered a counterpoint to more robust or overtly narrative depictions of women.

The emphasis on mood and suggestion over narrative in Dewing's work was a significant contribution. In an era when storytelling in art was still highly valued, Dewing's paintings often eschewed clear narratives, inviting viewers to engage on a more emotional and intuitive level. This approach prefigured later artistic developments that moved further away from literal representation towards abstraction and subjective experience.

While the rise of Modernism in the early 20th century overshadowed Tonalism and the academic traditions Dewing represented, his work never entirely disappeared from view, thanks in large part to patrons like Charles Lang Freer who ensured its preservation in public collections. The Freer Gallery of Art, in particular, stands as a testament to Dewing's enduring appeal and artistic merit. His paintings are also held in other major institutions, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Art Institute of Chicago, ensuring their accessibility for study and appreciation.

The late 20th and early 21st-century revival of interest in American Tonalism has brought Dewing's work back into the spotlight for art historians, curators, and collectors. Scholarly research and exhibitions have shed new light on his contributions and his place within the broader context of American art history. This renewed appreciation has helped to solidify his legacy and introduce his unique aesthetic to new audiences.

While it may be difficult to trace a direct line of stylistic imitation from Dewing to major figures of later 20th-century art, his influence can be seen more broadly in the continuing tradition of American painters who explore themes of introspection, quietude, and the poetic qualities of light and atmosphere. His dedication to craftsmanship and his pursuit of a deeply personal vision serve as an enduring example. The quiet elegance and psychological subtlety of his work continue to offer a contemplative respite, securing Thomas Wilmer Dewing's place as a distinctive and important voice in the history of American art.