Paul Elie Ranson stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the vibrant tapestry of late 19th and early 20th-century French art. A founding member of the influential Nabis group, Ranson's work bridged Symbolism, Art Nouveau, and a profound interest in the decorative arts, leaving a distinct mark on the artistic landscape of his time. His exploration of color, form, and spiritual themes, deeply influenced by Japanese art and esoteric philosophies, contributed to a radical rethinking of painting's purpose and potential.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born on March 29, 1861, in Limoges, France, Paul Elie Ranson hailed from a family with a background in local politics. This upbringing, while not directly artistic, likely provided a stable foundation for his later pursuits. His early artistic inclinations led him to study at the École des Arts Décoratifs in Limoges before he made the pivotal move to Paris in 1886. This relocation was crucial, as Paris was the undisputed epicenter of artistic innovation in Europe.

In Paris, Ranson enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, a private art school known for its progressive atmosphere and for welcoming students who sought alternatives to the rigid academicism of the École des Beaux-Arts. It was at the Académie Julian that Ranson would encounter a cohort of like-minded young artists who would soon form the nucleus of the Nabis. Among these were Paul Sérusier, Maurice Denis, Pierre Bonnard, and Édouard Vuillard. His formal training provided him with technical skills, but it was the intellectual and artistic ferment of Paris and his interactions with his peers that would truly shape his artistic vision.

The Genesis of Les Nabis

The Nabis (from the Hebrew word "nebiim," meaning prophets or seers) officially coalesced around 1888-1889. The catalyst for their formation was Paul Sérusier's return from Pont-Aven, where he had painted a small, highly abstracted landscape on a cigar box lid under the direct guidance of Paul Gauguin. This painting, dubbed Le Talisman, became a foundational object for the group, embodying Gauguin's advice to Sérusier: "How do you see these trees? They are yellow. So, put in yellow; this shadow, rather blue, paint it with pure ultramarine; these red leaves? Put in vermilion."

Ranson was immediately drawn to this new approach, which emphasized subjective experience, emotional truth, and the expressive power of pure color and simplified form over literal representation. He, along with Sérusier, Maurice Denis, Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, Ker-Xavier Roussel, and later Félix Vallotton and Aristide Maillol, embraced the idea that a painting was, before being a battle horse, a nude woman, or some anecdote, "essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order," as famously articulated by Denis. Ranson quickly became a central figure within this burgeoning group, not just as a painter but also as a charismatic personality whose studio would become their regular meeting place.

Ranson's Artistic Style: Symbolism, Japonisme, and the Decorative

Paul Ranson's artistic output was diverse, encompassing painting, printmaking, tapestry design, stained glass, and even designs for puppet theatre. His style is characterized by a potent blend of Symbolism, a deep appreciation for Japanese art (Japonisme), and a commitment to the decorative.

Symbolism and Mysticism

Like many artists of his generation, Ranson was deeply interested in Symbolism, a literary and artistic movement that sought to express ideas and emotions through indirect, suggestive means rather than direct depiction. He was particularly drawn to the esoteric, the mystical, and the occult. His works often feature enigmatic figures, dreamlike landscapes, and a rich tapestry of symbols drawn from various sources, including Theosophy, Rosicrucianism, and even witchcraft. This spiritual dimension gave his art a distinctive, often unsettling, quality. He explored themes of life, death, spirituality, and the hidden forces of nature, imbuing his subjects with a sense of mystery and inner meaning. Artists like Odilon Redon, a leading Symbolist, shared this inclination towards the dreamlike and the suggestive, though Ranson's approach was often more overtly decorative.

The Enduring Influence of Japonisme

The Nabis, as a group, were profoundly influenced by Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints, which had become widely available in Paris following the opening of Japan to the West. Artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige captivated them with their bold compositions, flat areas of unmodulated color, asymmetrical designs, high viewpoints, and decorative patterning. Ranson, in particular, absorbed these lessons deeply. His lithograph Tigre dans le jungle (Tiger in the Jungle, c. 1893) is a prime example, showcasing sinuous lines reminiscent of Japanese calligraphy, vibrant, non-naturalistic colors, and a flattened perspective that prioritizes decorative effect over spatial illusion. This embrace of Japanese aesthetics was a radical departure from Western academic traditions and was shared by contemporaries like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and even Vincent van Gogh, who also collected and studied Japanese prints.

A Champion of the Decorative Arts

Ranson and the Nabis sought to break down the traditional hierarchy that elevated "fine art" (painting and sculpture) above the "decorative arts." They believed that art should permeate all aspects of life and that everyday objects could be imbued with artistic beauty and meaning. Ranson was particularly active in this sphere, designing tapestries, wallpaper, ceramics, and stained glass. His designs often featured stylized natural forms, flowing lines characteristic of Art Nouveau, and the symbolic imagery found in his paintings. This commitment to the decorative aligned him with figures like William Morris in England and the broader Arts and Crafts movement, as well as the burgeoning Art Nouveau style championed by artists like Hector Guimard and Alphonse Mucha in Paris. His tapestry designs, often executed by his wife, Marie-France Rousseau, were particularly notable for their rich colors and intricate patterns.

Key Works and Their Significance

Paul Ranson's oeuvre, while perhaps not as voluminous as some of his Nabis contemporaries, contains several key works that encapsulate his artistic vision.

Femmes se coiffant (Women Combing Their Hair, c. 1892): This painting, also known as Two Nudes, is a quintessential Nabis work. It depicts two female figures in an intimate, domestic setting, their forms simplified and rendered with flowing, sinuous lines. The colors are soft and harmonious, and the composition has a distinctively decorative quality, almost like a tapestry. The work eschews traditional modeling and perspective, focusing instead on pattern and surface. The influence of Japanese prints is evident in the flattened space and the emphasis on silhouette. It reflects the Nabis' interest in intimate, everyday scenes, often featuring women, which was also a common theme for Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, who were known as "Intimists."

Tigre dans le jungle (Tiger in the Jungle, c. 1893): This color lithograph is one of Ranson's most iconic images. A stylized, almost heraldic tiger prowls through a dense, decorative jungle. The forms are highly abstracted, the colors vibrant and non-naturalistic, and the lines possess a calligraphic energy. The work perfectly illustrates Ranson's synthesis of Japanese aesthetics with his own Symbolist inclinations. The tiger itself can be seen as a symbol of primal energy or hidden desires, a common trope in Symbolist art. The decorative patterning of the foliage is a hallmark of his style.

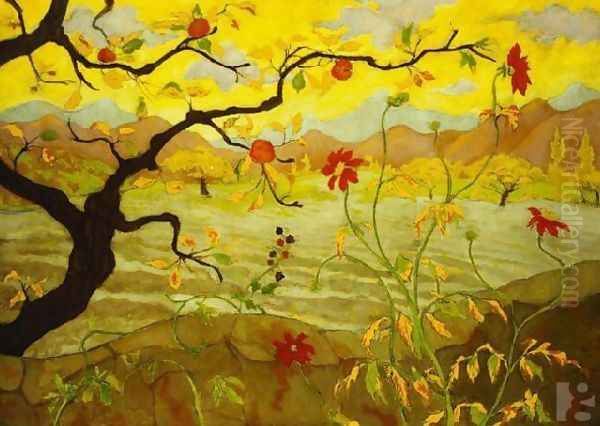

Apple Tree With Red Fruit (c. 1890s): This work, sometimes titled Nabi Landscape, showcases Ranson's ability to transform a simple natural scene into a symbolic and decorative statement. The apple tree, laden with vibrant red fruit, is rendered with bold, simplified forms and rich, almost jewel-like colors. The composition is flattened, and the overall effect is one of intense, almost mystical, beauty. The apple tree itself is a potent symbol in many cultures, often associated with knowledge, temptation, or paradise, adding layers of meaning to the work. This piece, with its emphasis on color and pattern, prefigures some of the concerns of later movements like Fauvism.

Lustral (Purification, c. 1891): This painting delves into Ranson's interest in ritual and mysticism. The title itself suggests a purification ceremony. The figures are stylized, and the scene is imbued with a sense of solemnity and spiritual significance. The use of color and line contributes to the otherworldly atmosphere. It reflects Ranson's engagement with esoteric themes, which set him somewhat apart even within the Nabis, though Maurice Denis also explored religious and spiritual subjects, albeit often from a more overtly Christian perspective.

Witch with a Black Cat (c. 1893): This work directly addresses Ranson's fascination with the occult. The depiction of the witch is not a grotesque caricature but rather an enigmatic figure, embodying arcane knowledge and a connection to unseen forces. The black cat, a traditional familiar, enhances the mystical atmosphere. The style remains decorative and symbolic, using color and form to evoke mood rather than to depict reality.

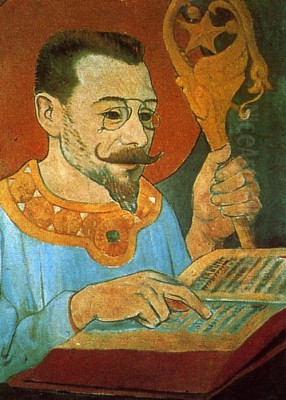

"Le Temple": A Hub for the Nabis

Paul Ranson's studio, located on Boulevard du Montparnasse, became the regular Saturday meeting place for the Nabis. Affectionately nicknamed "Le Temple" (The Temple) by the group, it was more than just a workspace; it was an intellectual and social hub. Here, the artists would discuss their ideas, critique each other's work, and engage in lively debates about art, literature, philosophy, and mysticism. Ranson, often referred to as "the Nabi more Japanese than the Japanese Nabi," was a warm and engaging host. His wife, Marie-France Rousseau, whom he married in 1888 and who was also an artist and his cousin, played an integral role in these gatherings.

These meetings were crucial for fostering the Nabis' collective identity and for the cross-pollination of ideas. They often involved rituals and playful ceremonies, reflecting the group's esoteric leanings and their desire to create a unique artistic brotherhood. The atmosphere at "Le Temple" was one of creative ferment and shared purpose, contributing significantly to the development and cohesion of the Nabis movement.

The Académie Ranson

In 1908, a year before his untimely death, Paul Ranson, with the encouragement and active participation of Marie-France, founded the Académie Ranson. This art school was established to propagate the Nabis' artistic principles and to offer an alternative to more traditional art education. The Nabis believed in the importance of individual expression, the synthesis of art and life, and the expressive power of color and design.

After Ranson's death in February 1909 from typhoid fever at the young age of 47, Marie-France Rousseau Ranson took over the direction of the academy. She ensured its continuation and invited many of Ranson's Nabis colleagues to teach there. Maurice Denis and Paul Sérusier were among the prominent artists who taught at the Académie Ranson, alongside others like Ker-Xavier Roussel, Félix Vallotton, and later, sculptors like Aristide Maillol. The Académie Ranson remained an important institution for many years, attracting students who sought a more modern and individualistic approach to art. It played a role in transmitting Nabis ideals to a new generation of artists, including figures like Roger de La Fresnaye, who would later be associated with Cubism, and the sculptor François Pompon.

Later Life, Death, and Enduring Legacy

Paul Ranson's artistic career, though relatively short, was intensely productive. His health, however, was often fragile. He passed away on February 20, 1909, in Paris. Despite his early death, his influence was considerable, both through his own work and through his role within the Nabis and the founding of the Académie Ranson.

Ranson's legacy lies in his contribution to the Nabis' redefinition of painting as a vehicle for subjective expression and decorative beauty. His embrace of Symbolism, his pioneering use of color, and his fascination with Japanese art helped to pave the way for many of the key developments in early 20th-century modernism.

His emphasis on the decorative, the flat application of color, and stylized forms can be seen as a precursor to aspects of Fauvism, particularly in the work of artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain, who pushed color to even greater expressive autonomy. The Nabis' general interest in pattern and design also resonated with the Art Nouveau movement. Furthermore, the Nabis' exploration of subjective and spiritual themes contributed to the broader anti-naturalist tendencies that characterized much of modern art, influencing movements that sought to explore inner worlds, such as Surrealism, albeit indirectly.

While artists like Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard may be more widely recognized today, Paul Ranson's role as a catalyst, a theorist (within the group), and a highly original artist was crucial to the Nabis' identity and impact. His work continues to be appreciated for its unique blend of mysticism, decorative elegance, and bold experimentation. His commitment to integrating art into everyday life through the decorative arts also remains a relevant and inspiring aspect of his career. His paintings and prints are held in major museum collections worldwide, testament to his enduring, if sometimes quiet, significance in the history of modern art. His exploration of the spiritual and the symbolic, combined with a sophisticated decorative sense, ensures his place as a distinctive voice from a period of profound artistic transformation.