Jean-Jacques de Boissieu stands as a significant figure in eighteenth-century French art, particularly renowned for his mastery of etching and printmaking. Born in Lyon in 1736 and dying there in 1810, his life spanned a tumultuous period in French history, yet his artistic focus remained remarkably consistent. He carved a unique niche for himself, drawing profound inspiration from the Dutch Golden Age masters, most notably Rembrandt, earning him the enduring moniker "the French Rembrandt." While also a painter and draughtsman, it was through the intricate lines and tonal subtleties of his etchings that de Boissieu achieved his most lasting fame, capturing the landscapes, people, and daily life of his time with sensitivity and technical brilliance.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Lyon

Jean-Jacques de Boissieu hailed from a noble family in Lyon, a city with a rich cultural and economic history. Born into privilege, his path could have easily led to a career in medicine or law, fields his family might have preferred. However, de Boissieu demonstrated an early and unwavering passion for the visual arts. He began his artistic training in his hometown, immersing himself in drawing and likely receiving initial instruction from local masters, though specific names from this earliest period are scarce.

Lyon itself provided a fertile ground for his developing eye. The city's bustling commercial life, its surrounding picturesque landscapes along the Rhône and Saône rivers, and its distinct urban character offered ample subjects. It was here, between 1758 and 1759, that de Boissieu produced his first known etchings, often depicting scenes from Lyon and its environs. These early works already hinted at his keen observational skills and his burgeoning interest in the expressive potential of the etched line. His decision to pursue art, particularly the less traditionally aristocratic field of printmaking, marked him as an individualist early on.

Parisian Horizons and Influential Encounters

Seeking broader artistic horizons, de Boissieu relocated to Paris around 1761, remaining there until 1764. The French capital was the undisputed center of the European art world, offering exposure to leading artists, influential collectors, and the latest aesthetic debates. This period proved crucial for his development and integration into the wider artistic community. He formed connections with several prominent figures who would shape his career and outlook.

Among his notable acquaintances were the highly respected German-born engraver Jean-Georges Wille, whose technical precision was widely admired, and the celebrated painter Jean-Baptiste Greuze, known for his sentimental genre scenes and moralizing narratives. He also associated with Claude-Joseph Vernet, the preeminent landscape and marine painter whose atmospheric works were immensely popular. These interactions provided invaluable opportunities for artistic exchange and learning, exposing de Boissieu to different techniques and approaches.

Furthermore, de Boissieu gained the attention and encouragement of influential collectors and connoisseurs like Pierre-Jean Mariette, a renowned art historian and collector, and Claude-Henri Watelet, himself an accomplished amateur etcher and writer on art theory. Their support and validation would have been significant for a young artist establishing his reputation. While direct collaborative projects with these artists are not documented, the stimulating environment of the Parisian art scene undoubtedly refined his skills and broadened his artistic perspective.

The Grand Tour: Italian Landscapes and Inspiration

A pivotal experience in de Boissieu's life and artistic journey was his trip to Italy between 1765 and 1766. He traveled in the company of Alexandre François, Duc de La Rochefoucauld, a common practice for artists seeking patronage and the broadening experience of the Grand Tour. Italy, with its classical ruins, Renaissance masterpieces, and stunning natural scenery, offered a wealth of inspiration.

During his Italian sojourn, de Boissieu dedicated himself to drawing and etching the landscapes he encountered. The Roman Campagna, the ruins of antiquity, and the vibrant street life provided fresh subject matter. His Italian works often display a sensitivity to light and atmosphere, capturing the specific character of the Mediterranean environment. This experience deepened his appreciation for landscape as a genre and likely reinforced his affinity for realistic depiction over idealized or purely decorative styles.

An anecdote often recounted is his meeting with the philosopher Voltaire during this period, though details remain sparse. Regardless, the Italian journey was transformative, enriching his visual vocabulary and solidifying his commitment to landscape and observational drawing. The sketches and studies made during this time would serve as source material for later works produced back in France.

Return to Lyon: Maturity and Recognition

Around 1771, Jean-Jacques de Boissieu made the definitive move back to his native Lyon, where he would reside for the remainder of his life. This return did not signify a retreat from the art world but rather a consolidation of his career in a familiar and supportive environment. His reputation was by now well-established, both locally and further afield.

His standing was further cemented by an appointment in 1771 as a treasurer of France in the generality of Lyon (Trésorier de France au bureau des finances de la généralité de Lyon). This official position provided him with a degree of financial security and social standing, allowing him greater freedom to pursue his artistic endeavors without constant commercial pressure. It reflected his family's noble status but also his own respected position within the Lyonnais community.

De Boissieu became a central figure in Lyon's artistic life. He was actively involved in local cultural institutions and played a role in the founding or development of the city's art school, contributing to the education of younger artists. Despite his official duties and social connections, accounts suggest he maintained a somewhat reserved, even reclusive, lifestyle, dedicating himself primarily to his studio work. His home became a hub for local artists and connoisseurs.

The "French Rembrandt": Style and Technique

The comparison to Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn is central to understanding de Boissieu's artistic identity. This was not merely a casual compliment but reflected deep affinities in technique, subject matter, and sensibility. Like the Dutch master, de Boissieu excelled in etching and drypoint, exploring the full potential of these media for creating rich tonal variations and expressive lines.

His mastery of chiaroscuro – the dramatic interplay of light and shadow – is evident throughout his work. He used dense networks of cross-hatching and delicate, spaced lines to render textures, capture the fall of light on different surfaces, and create a palpable sense of atmosphere. Whether depicting the dim interior of a peasant cottage, the dappled sunlight in a forest, or the weathered face of an old man, his control over light and shadow was exceptional.

De Boissieu often worked with black or bistre (brownish) ink, sometimes applying washes to his drawings to enhance tonal depth, a technique also favored by Rembrandt. His prints are characterized by their meticulous detail, yet they avoid stiffness, retaining a sense of life and immediacy. He shared with Rembrandt and other Dutch Golden Age artists, such as Adriaen van Ostade, an interest in depicting everyday life and common people – peasants, artisans, schoolmasters, quack doctors – with empathy and dignity, largely eschewing the Rococo frivolity favored by some Parisian contemporaries like François Boucher or Jean-Honoré Fragonard.

Diverse Subjects: Landscapes, Genre, and Portraits

De Boissieu's oeuvre is notable for its thematic range, though unified by his distinctive style. Landscapes formed a significant part of his output. He depicted the specific scenery around Lyon, the banks of the Rhône and Saône, wooded areas, and rural settings with a naturalism that was advanced for its time in France. His Italian journey also yielded numerous landscape studies and prints. These works often possess a quiet, contemplative mood, focusing on the effects of light and weather. His approach influenced the development of landscape painting and printmaking in France, moving towards greater realism.

Genre scenes were another major focus. Works like The Schoolmaster (Le Maître d'école), The Quack Doctor (Le Charlatan), or The Cooper (Le Tonnelier) offer intimate glimpses into the lives of ordinary people. These scenes are rendered without overt sentimentality but with a keen eye for human interaction and environmental detail. They reflect the burgeoning interest in bourgeois and rural life characteristic of the later Enlightenment, finding resonance with collectors who appreciated their realism and perceived honesty.

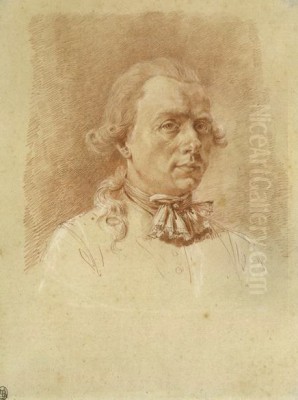

Portraits, including several striking self-portraits, also feature in his work. These often display psychological insight, capturing the sitter's character through careful observation of facial features and expression. His Studies of Heads (Têtes d'études) are particularly noteworthy, showcasing his skill in rendering diverse physiognomies and emotional states, again echoing Rembrandt's practice. He also produced studies of animals and architectural details, demonstrating his broad curiosity and commitment to drawing from life.

Representative Works: A Glimpse into his World

While de Boissieu produced a large body of work, certain prints stand out as particularly representative of his skill and thematic concerns. His self-portraits, executed at various stages of his life, offer compelling insights into the artist's introspective nature and technical evolution.

The Quack Doctor (Le Charlatan) and The Schoolmaster (Le Maître d'école) are among his most famous genre scenes, admired for their lively composition, detailed settings, and nuanced depiction of characters. They capture vignettes of provincial life with humor and realism.

His landscapes, such as The Large Mill (Le Grand Moulin) or views around Lyon and in Italy, showcase his ability to render complex natural forms and atmospheric effects. Works like Landscape with Washerwomen combine landscape and genre elements, depicting figures naturally integrated into their environment.

Prints like The Cooper (Le Tonnelier) or The Card Players highlight his interest in artisans and peasant life. His series of Studies of Heads demonstrates his exceptional draughtsmanship and ability to capture individual character in a few deft lines. These works, widely circulated as prints, cemented his reputation across Europe.

Influence, Legacy, and the Revival of Etching

Jean-Jacques de Boissieu played a crucial role in the revival of etching as a major artistic medium in France during the latter half of the eighteenth century. At a time when reproductive engraving often dominated the print market, de Boissieu championed etching as a means of original artistic expression, much like Rembrandt had done over a century earlier. His technical virtuosity and the aesthetic appeal of his prints inspired contemporaries and followers.

His influence extended to younger artists. Michel Grobon, another Lyon-based artist, was encouraged by his friendship with de Boissieu to explore etching. The printmaker Ignace Joseph de Claussin is known to have created etchings that directly copied or were heavily inspired by de Boissieu's designs, attesting to the older artist's prestige. While perhaps less overtly revolutionary than some figures of the era, his dedication to printmaking and his distinctive style left a significant mark. Other French printmakers active during or shortly after his time, such as Charles-Nicolas Cochin or Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, worked in different styles but were part of the same broader milieu where printmaking was gaining renewed appreciation.

De Boissieu's aesthetic, often described as reflecting late eighteenth-century bourgeois values, emphasized realism, intimacy, and technical skill over aristocratic grandeur or Rococo lightness. His work appealed to a growing audience of collectors who valued careful observation and relatable subject matter. His focus on local landscapes also contributed to a greater appreciation for regional scenery in French art.

Later Years and Enduring Reputation

De Boissieu continued to work prolifically in Lyon throughout the turbulent years of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic era. While the political upheavals undoubtedly impacted life in Lyon, his artistic production seems to have remained relatively steady. His established reputation and perhaps his somewhat withdrawn nature may have shielded him from the worst of the turmoil. There are mentions in some sources of possible legal disputes or misunderstandings later in his life, but these remain secondary to his artistic achievements.

He passed away in Lyon in 1810, leaving behind a substantial body of work comprising hundreds of etchings, drawings, and paintings. His death marked the end of a long and dedicated career that significantly enriched French printmaking. His reputation endured through the nineteenth century and beyond, recognized for his technical mastery and his unique position bridging Dutch traditions and French sensibilities.

Today, Jean-Jacques de Boissieu's works are held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Louvre Museum in Paris, the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, the British Museum in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Hessisches Landesmuseum in Darmstadt, and the Fondation Beyeler in Switzerland. His prints continue to be studied and admired by curators, collectors, and art historians for their technical brilliance, their sensitive portrayal of the world he inhabited, and their important place in the history of European art.

Conclusion: A Master of Line and Light

Jean-Jacques de Boissieu remains a compelling figure in eighteenth-century art. As the "French Rembrandt," he successfully adapted the spirit and techniques of the Dutch masters to a French context, creating a body of work characterized by its technical finesse, observational acuity, and quiet dignity. His mastery of etching allowed him to explore the nuances of light, texture, and atmosphere with remarkable subtlety. Through his landscapes, genre scenes, and portraits, he provided an invaluable visual record of Lyon and its surroundings, and of the lives of ordinary people during his time. A central figure in Lyon's artistic life and a key player in the revival of original printmaking in France, de Boissieu's legacy endures in the enduring appeal and historical significance of his meticulously crafted works.