Hendrick Goudt stands as a fascinating, albeit somewhat enigmatic, figure in the rich tapestry of Dutch Golden Age art. Though his surviving authenticated oeuvre is remarkably small, consisting of just seven engravings and a few drawings, his impact on the development of printmaking and the dissemination of a particular artistic vision was profound. He was a nobleman by birth, an artist by choice, and a crucial conduit for the influential style of the German painter Adam Elsheimer. Goudt's mastery of light and shadow in the demanding medium of engraving set a new standard and left an indelible mark on subsequent generations of artists, including some of the era's greatest luminaries.

Noble Beginnings and an Artistic Inclination

Hendrick Goudt was born into a distinguished and wealthy family, a background not typical for most artists of his time. The exact year of his birth is debated by scholars, with sources pointing to either 1583 or 1585. His birthplace was Utrecht, a city that would later become a significant center for artistic innovation, particularly for painters influenced by Caravaggio. His grandfather, also named Hendrick, was a high-ranking official in The Hague, and his father, Arend Goudt, served as the mayor of Utrecht. This privileged upbringing likely afforded him access to education and culture, which may have nurtured his early artistic interests.

Details about Goudt's earliest artistic training are scarce. It is believed he received some initial instruction in printmaking in The Hague, a city with a burgeoning art scene. However, the most formative period of his artistic development undoubtedly occurred when he traveled to Rome, the magnetic center of the art world in the early 17th century. It was here that his path would cross with an artist who would define his career: Adam Elsheimer.

The Roman Sojourn: A Fateful Encounter with Adam Elsheimer

Around 1604, Hendrick Goudt arrived in Rome. The city was a melting pot of artistic styles and talents, attracting artists from all over Europe. It was here that Goudt encountered Adam Elsheimer (1578–1610), a German painter from Frankfurt who had settled in Rome around 1600. Elsheimer, though his own output was also small and meticulously crafted, was a painter of extraordinary originality and influence. He specialized in small-scale cabinet paintings on copper, often depicting biblical or mythological scenes set within evocative, poetically lit landscapes. His innovative use of chiaroscuro, his ability to capture varied light effects (moonlight, firelight, twilight), and the intimate, human emotion in his figures deeply impressed his contemporaries.

Goudt became more than just a student to Elsheimer; he was also a friend, a patron, and, for a time, his housemate. This close association, lasting until Elsheimer's premature death in 1610, was pivotal. Goudt absorbed Elsheimer's artistic principles, particularly his fascination with nocturnal scenes and dramatic lighting. It seems Goudt dedicated himself almost exclusively to translating Elsheimer's painted visions into the graphic medium of engraving. This was no mere act of reproduction; Goudt's engravings were interpretations that captured the spirit and atmosphere of Elsheimer's work with remarkable sensitivity and technical brilliance.

There are some historical accounts, notably from Joachim von Sandrart, a German painter and art historian who also knew Elsheimer, suggesting that Goudt's financial dealings may have contributed to Elsheimer's debts and eventual imprisonment, which purportedly hastened his death. However, these claims are not definitively substantiated and remain a somber, debated footnote to their otherwise fruitful artistic relationship. What is certain is that Goudt held Elsheimer's art in the highest esteem and dedicated his own artistic efforts to its popularization.

The Seven Engravings: A Small but Potent Legacy

Hendrick Goudt's fame rests almost entirely on a series of seven engravings, all created after paintings by Adam Elsheimer. These prints were executed between 1608 and 1613, some during Elsheimer's lifetime and others shortly after his death. Each print is a testament to Goudt's technical virtuosity and his profound understanding of Elsheimer's aesthetic.

One of his earliest prints is Tobias and the Angel (1608), often referred to as the "Small Tobias" to distinguish it from a later, larger version. This work already showcases Goudt's ability to render subtle gradations of light and texture, capturing the nocturnal atmosphere of Elsheimer's original. The figures are enveloped in a soft darkness, with highlights picking out key elements of the composition.

Ceres Seeking Proserpine, also known as The Mocking of Ceres (1610), is another masterful night scene. The print depicts the goddess Ceres, torch in hand, searching for her abducted daughter. The flickering torchlight illuminates the central figures and casts deep shadows, creating a dramatic and emotionally charged scene. Goudt's intricate network of lines builds up rich, velvety blacks that were unparalleled in engraving at the time.

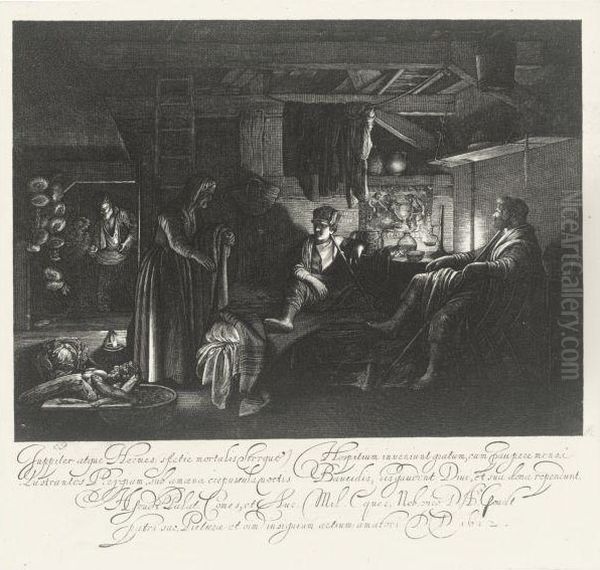

In 1612, Goudt produced Jupiter and Mercury in the House of Philemon and Baucis. Based on Ovid's Metamorphoses, the scene shows the humble elderly couple unknowingly entertaining the gods in disguise. The interior is lit by a modest fire and a lamp, and Goudt expertly conveys the warm, intimate glow, contrasting it with the surrounding darkness. The textures of simple furnishings and aged figures are rendered with meticulous care.

Perhaps his most famous and influential print is The Flight into Egypt (1613). Elsheimer's original painting was revolutionary for its depiction of a biblical scene within a realistic, moonlit landscape, complete with reflections in water and a detailed starry sky showing the Milky Way. Goudt's engraving brilliantly translates this complex interplay of light sources – the moon, the stars, and the campfire of shepherds – into the linear language of print. The deep, atmospheric darkness and the subtle luminosity achieved in this print had a profound impact on artists like Rembrandt.

The series also includes a larger version of Tobias and the Angel (1613), Aurora (1613), depicting the goddess of dawn in a luminous, early morning sky, and Balaam and the Ass (or The Prophet Balaam and the Angel), which, while sometimes debated in its attribution or exact dating, fits within this group of Elsheimer-inspired works. Each of these prints demonstrates Goudt's consistent pursuit of capturing Elsheimer's unique handling of light and atmosphere.

Artistic Style and Technical Innovation

Hendrick Goudt was a pioneer in the techniques of engraving, particularly in achieving rich, dark tones and dramatic chiaroscuro effects that rivaled painting. His style is often described as a form of "tenebrism" in print, characterized by stark contrasts between light and dark. He achieved his signature velvety blacks through a dense and patient application of cross-hatching and stippling, using the burin with exceptional control.

Unlike many reproductive engravers who sought merely to copy a composition, Goudt aimed to translate the painterly qualities of Elsheimer's work. He understood that light was not just an element of composition for Elsheimer, but a primary means of conveying mood and narrative. Goudt's lines are not merely outlines; they swell and diminish, cluster and disperse, to create volume, texture, and, above all, atmosphere. The unengraved white of the paper becomes an active element, representing the brightest highlights and contrasting sharply with the deeply worked shadows.

Another characteristic feature of Goudt's prints is the elegant calligraphy often found in the inscriptions, which typically include his name, Elsheimer's name as the inventor, the date, and sometimes a dedication or title. This attention to the textual elements further underscores the refinement and high quality of his productions. His prints were clearly intended as luxury objects for discerning collectors.

Goudt's technical innovations were significant. Before him, achieving such deep and varied blacks in engraving was rare. His work demonstrated new possibilities for the medium, pushing its expressive range and influencing how subsequent artists approached the challenge of rendering light and shadow in print.

Return to Utrecht, Later Life, and Tragic Decline

Following Adam Elsheimer's death in December 1610, Hendrick Goudt remained in Rome for a short period. In 1611, he returned to his native Utrecht, bringing with him a number of Elsheimer's paintings and drawings, as well as the copper plates for his engravings. Upon his return, he registered with the Utrecht Guild of Saint Luke, the city's professional organization for painters and other artists.

His engravings after Elsheimer quickly gained international acclaim, circulating throughout Europe and influencing a wide range of artists. He continued to issue impressions from his plates, and these prints became highly sought after. Despite this success, Goudt's own artistic production seems to have ceased after 1613, the date of his last known engravings.

Tragically, Goudt's later life was marred by mental illness. Around 1620, he began to show signs of intellectual decline. Contemporary sources, including the physician Johan van Beverwijck, mention that he suffered from a "weakness of the head" or "madness," possibly induced by an aphrodisiac. By 1624 or 1625, his condition had deteriorated to the point where he was declared mentally incompetent, and his affairs were placed under guardianship.

The exact date of his death, like his birth, has been subject to some scholarly debate. While some older sources suggested a death year around 1630, more recent research and documentary evidence point to his death occurring in Utrecht on December 17, 1648. He was buried in the Buurkerk, a prominent church in Utrecht.

Influence and Enduring Legacy

Despite his small output and the tragic end to his active career, Hendrick Goudt's influence on 17th-century art was substantial, primarily through the dissemination of Adam Elsheimer's artistic ideas. Elsheimer himself, while admired by fellow artists in Rome like Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), who lamented his early death and praised his skill, might have remained a more localized phenomenon without Goudt's widely circulated prints.

Goudt's engravings were instrumental in spreading Elsheimer's innovative approach to landscape, his poetic night scenes, and his dramatic use of light. Artists across Europe, particularly in the Netherlands, were exposed to these ideas through Goudt's prints.

The most significant artist to absorb lessons from Goudt's (and by extension, Elsheimer's) work was Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669). Rembrandt, a master etcher himself, was profoundly interested in capturing psychological depth and dramatic atmosphere through chiaroscuro. Goudt's prints, especially The Flight into Egypt, provided a powerful precedent for Rembrandt's own nocturnal etchings, such as his own Flight into Egypt (1651) or The Adoration of the Shepherds: A Night Piece (c. 1652). Rembrandt's rich, dark tones and his experimental approach to etching owe a debt to the expressive possibilities demonstrated by Goudt.

Another Dutch artist deeply influenced was Hercules Segers (c. 1589/90–c. 1638), an experimental printmaker known for his melancholic landscapes and innovative techniques. Segers's moody, atmospheric prints share a kinship with the tonalities Goudt achieved. Jan van de Velde II (c. 1593–1641) was another printmaker who specialized in landscapes and genre scenes, and his night scenes clearly show an awareness of Goudt's work.

The influence extended to painters as well. The poetic, often moonlit, landscapes of Aert van der Neer (1603/04–1677) resonate with the atmosphere popularized by Elsheimer and Goudt. Even the great French classical landscape painter Claude Lorrain (1600–1682), who spent most of his career in Rome, was familiar with Elsheimer's work, and Goudt's prints would have further reinforced the appeal of idyllic, luminist landscapes.

In Utrecht itself, artists like Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651), a leading figure and teacher, would have been aware of Goudt's work upon his return. While the Utrecht Caravaggisti, such as Hendrick ter Brugghen (1588–1629) and Gerrit van Honthorst (1592–1656), drew their primary inspiration from Caravaggio's dramatic realism and tenebrism, the general interest in strong light effects in Utrecht created a receptive environment for Goudt's art. The "Pre-Rembrandtists," such as Rembrandt's own teacher Pieter Lastman (1583–1633) in Amsterdam, were also part of a generation deeply impressed by Elsheimer's narrative intensity and light effects, which Goudt's prints helped to popularize. Other Italianate landscape painters active in the Netherlands, like Cornelis van Poelenburgh (1594/95–1667) and Bartholomeus Breenbergh (1598–1657), who also spent time in Italy, were part of this broader artistic current that valued atmospheric lighting and poetic interpretations of nature and narrative, themes central to the Elsheimer-Goudt legacy. Even the renowned Flemish master Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), a contemporary of Goudt, was an avid collector of prints and would have undoubtedly known Goudt's influential works.

A Singular Vision in Black and White

Hendrick Goudt's career was brief, his output limited, yet his contribution to art history is undeniable. As a scion of a noble family, he chose the demanding path of an artist, dedicating his exceptional talent to immortalizing the unique vision of Adam Elsheimer. His seven engravings are masterpieces of the printmaker's art, showcasing an unprecedented command of light and shadow that expanded the expressive potential of the medium.

Through his work, the intimate, poetic, and luminist art of Elsheimer reached a far wider audience than his paintings alone ever could have. Goudt's prints became a vital source of inspiration for some of the greatest artists of the Dutch Golden Age and beyond, influencing the development of landscape painting, nocturnal scenes, and the art of etching itself. He remains a testament to the power of a singular artistic focus and the profound impact that even a small body of work can have when executed with genius and dedication. His luminous engravings continue to captivate viewers with their atmospheric depth and technical brilliance, securing his place as a key, if specialized, master of 17th-century European art.