Jehan Georges Vibert stands as a fascinating figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century French art. Born in Paris on September 30, 1840, and passing away in the same city on July 28, 1902, Vibert carved a unique niche for himself within the dominant Academic tradition. While possessing the technical mastery expected of an artist trained in the rigorous French system, he became most renowned for his witty, often satirical, depictions of everyday life, particularly focusing on the clergy of the Roman Catholic Church. His work, infused with humour and meticulous detail, found immense popularity during his lifetime, especially in France and the United States, making him a commercially successful artist whose legacy offers insight into the tastes and social commentary of his era. Beyond painting, Vibert was a man of diverse talents, engaging in sculpture, playwriting, and even invention, showcasing a restless creativity that extended beyond the canvas.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Vibert's entry into the world of art seemed almost preordained. He hailed from a family deeply involved in the arts and creative pursuits. His paternal grandfather was Théodore Vibert, a notable engraver and publisher, while his maternal grandfather was the celebrated engraver Jean-Pierre-Marie Jazet. This artistic lineage provided an environment where creative skill was valued and likely encouraged from a young age. Interestingly, his other paternal grandfather was Jean-Pierre Vibert, a renowned horticulturalist famous for his work in breeding roses, suggesting a family background rich in both artistic and meticulous, scientific pursuits.

His formal artistic training began under the tutelage of his maternal grandfather, Jazet, where he likely honed his skills in drawing and engraving. He furthered his studies in the atelier of Félix-Joseph Barrias, a painter known for his historical and religious subjects. This grounding in traditional methods prepared him for the next crucial step in an aspiring French artist's career: the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Vibert enrolled at the prestigious institution around the age of sixteen, a testament to his early promise.

At the École, Vibert studied under François-Édouard Picot, a respected history painter and portraitist who had himself been a student of Jacques-Louis David. Picot's studio was a significant training ground for many successful artists of the period. Immersion in the École's curriculum meant rigorous training in drawing from life and classical sculpture, anatomy, perspective, and art history. This environment fostered technical proficiency and adherence to the established canons of Academic art, emphasizing historical, mythological, or religious themes executed with polished finishes and clear narratives. His contemporaries, or those passing through the École system around the same time, included figures who would also achieve fame, such as Léon Bonnat and Jean-Jacques Henner, though their artistic paths would diverge.

Debut and Rise Through the Salon

The Paris Salon, the official art exhibition sponsored by the French state and organized by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was the primary venue for artists to gain recognition, attract patrons, and establish their careers in the nineteenth century. Making a successful debut at the Salon was crucial. Vibert first submitted works to the Salon in 1863, presenting two paintings: La Sieste (The Nap) and Repentir (Repentance). While these initial entries did not secure him a prize, they marked his official entry into the competitive Parisian art world and began to draw attention to his name.

His breakthrough came the following year, in 1864. Vibert exhibited Narcisse Changé en Fleur (Narcissus Transformed into a Flower), a mythological subject typical of Academic training. This painting earned him a gold medal, a significant honour that boosted his reputation considerably. However, the work also courted controversy due to its depiction of nudity, highlighting the often-conservative tastes of the Salon jury and public, even when dealing with classical themes. This early success demonstrated his technical skill and ambition within the established system.

Over the next few years, Vibert continued to exhibit at the Salon, exploring different themes. In 1866, he presented Daphnis et Chloé, another mythological subject. While this piece reportedly received criticism, perhaps again related to its classical sensuality or execution, he found more favourable reception that same year with a genre painting, Entrée des Toreros (Entrance of the Bullfighters). This work, depicting a scene inspired by Spanish culture, was praised for its lively composition and subject matter. It also marked a significant collaboration with the Spanish artist Eduardo Zamacois y Zabala, indicating Vibert's engagement with international artistic trends and his willingness to work alongside peers. This period shows Vibert navigating the expectations of the Salon, balancing classical subjects with the growing interest in genre scenes and contemporary life, albeit often with a historical or exotic flavour favoured by Academic painters like Jean-Léon Gérôme or William-Adolphe Bouguereau.

The Franco-Prussian War and its Impact

The trajectory of Vibert's life and career was interrupted, like that of many Frenchmen, by the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. France's swift and devastating defeat, the siege of Paris, and the subsequent political turmoil of the Paris Commune marked a traumatic period in the nation's history. Vibert demonstrated his patriotism by volunteering for service. He joined the francs-tireurs, irregular military forces or sharpshooters.

During the conflict, Vibert saw active combat. He participated in the Battle of Malmaison, fought in October 1870 as part of the efforts to break the siege of Paris. In this engagement, he was wounded. His bravery and service did not go unrecognized. For his actions during the war, he was awarded the prestigious Légion d'Honneur (Legion of Honour), France's highest order of merit. He was initially named a Chevalier (Knight) and later promoted to the rank of Officier (Officer) in 1882, reflecting continued esteem for his contributions and artistic stature.

While it's difficult to definitively trace the direct impact of the war experience on the specific subject matter of his later, more humorous works, such intense personal involvement in national conflict often shapes an individual's worldview. The trauma of war, the experience of societal upheaval, and perhaps a heightened awareness of human folly could have subtly informed the satirical edge that became increasingly prominent in his art during the subsequent decades of the French Third Republic. His demonstrated courage also added another dimension to his public persona beyond that of a skilled painter.

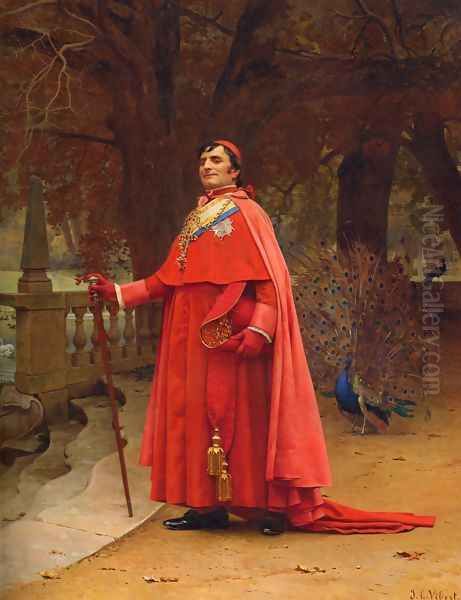

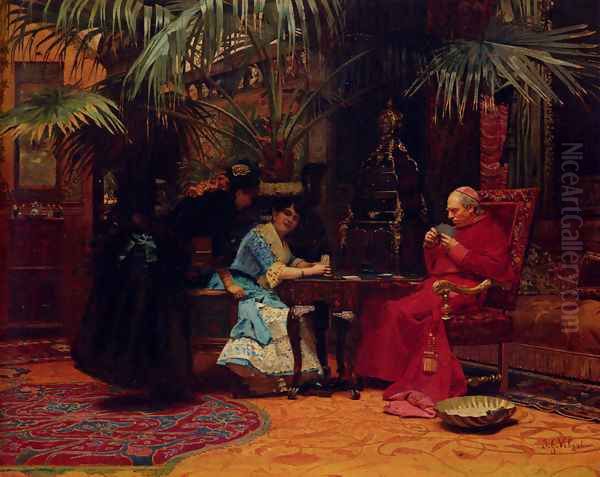

The Height of Academic Satire: The Cardinal Paintings

Following the war, Vibert's artistic focus increasingly shifted towards the genre that would define his popular reputation: satirical and humorous depictions of Roman Catholic clergy, particularly cardinals. These "Cardinal Paintings" became his trademark and were immensely popular with collectors, especially in America. Rather than grand religious narratives, Vibert portrayed high-ranking church officials in intimate, everyday settings, often engaged in mundane or slightly absurd activities that gently punctured their aura of solemnity and authority.

These works often showcased cardinals enjoying fine food and wine, playing games, engaging in hobbies, or interacting in ways that highlighted their very human, sometimes slightly self-indulgent, natures. A prime example is The Marvelous Sauce (also known as Le Cordon Bleu), painted in the 1890s. It depicts two cardinals in a kitchen setting, one enthusiastically tasting a sauce prepared by the other, who wears a chef's apron over his robes. The meticulous detail in the rendering of the kitchen, the food, and the cardinals' expressions combines technical virtuosity with gentle humour.

Another well-known work is The Missionary's Adventures (c. 1901), which shows a group of cardinals listening intently, perhaps with a mix of fascination and amusement, as a missionary recounts his experiences abroad, possibly exaggerating his tales. La Reprimande (The Reprimand) from 1874, while perhaps less overtly humorous, depicts an interaction suggesting internal church dynamics. These paintings resonated with a public in the French Third Republic, a period marked by significant political tension between the state and the Catholic Church, and a growing secularism and anti-clerical sentiment among parts of the population. Vibert's satire was generally light-hearted rather than vicious, more akin to gentle ribbing than a fierce attack, which likely contributed to its broad appeal. His approach differed significantly from the biting social and political caricature of an artist like Honoré Daumier, whose lithographs offered much sharper critiques of power structures.

Vibert's skill in rendering the rich fabrics and vibrant colours of clerical vestments was particularly noteworthy. He captured the luxurious textures of silk and satin, often employing a specific, brilliant red pigment that became known as "Vibert's Red," a colour he reportedly perfected or perhaps even invented for achieving the perfect shade for cardinals' robes. This attention to detail and colour added to the visual appeal and realism of his scenes, making the gentle satire even more effective. These works placed cardinals not in lofty cathedrals, but in comfortable, richly appointed domestic interiors, further emphasizing their worldly comforts.

Technical Mastery and Innovation

Underpinning Vibert's popular satirical subjects was a formidable technical skill honed through his rigorous Academic training. His paintings are characterized by meticulous draftsmanship, smooth finishes, and a high degree of realism in the rendering of figures, fabrics, and settings. He paid close attention to detail, ensuring that every element within the composition, from the pattern on a carpet to the reflection in a wine glass, was carefully observed and accurately depicted. This precision lent an air of authenticity to his scenes, even the humorous ones.

His handling of colour was particularly adept. As mentioned, he was associated with "Vibert's Red," but his palette extended to a rich range of hues, applied with skill to create convincing effects of light and texture. He mastered the depiction of luxurious materials – the sheen of silk, the softness of velvet, the gleam of polished wood, the transparency of glass. This technical virtuosity was a hallmark of the Academic tradition, which valued polished execution and verisimilitude, contrasting sharply with the looser brushwork and subjective colour of the burgeoning Impressionist movement led by artists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

Beyond his skill with the brush, Vibert possessed an inventive and scientific turn of mind, applying it directly to the materials and techniques of painting. He was deeply interested in the chemistry of pigments and varnishes, seeking ways to ensure the permanence and brilliance of his colours. He experimented with developing new pigments and improving existing ones. He also invented practical tools for artists, such as a specific type of easel and specialized paintbrushes designed for particular effects.

His interest in the technical aspects of art led him to write and publish on the subject. His book, La Science de la peinture (The Science of Painting), published in 1891, codified his research and thoughts on materials, techniques, colour theory, and the preservation of artworks. This publication demonstrated his desire to share his knowledge and contribute to the technical foundations of his craft, positioning him not just as a practitioner but also as a theorist and innovator in the practical aspects of painting. This scientific approach further distinguished him within the art world of his time.

Beyond Oil Painting: Watercolors and Other Ventures

While best known for his highly finished oil paintings, Jehan Georges Vibert was also a master of watercolor. In the late nineteenth century, watercolor painting was gaining increasing respect as a serious artistic medium in France, moving beyond its traditional association with preparatory sketches or amateur practice. Vibert played a significant role in elevating the status of watercolor in France.

In 1878, he showcased his watercolor works at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) held in Paris, demonstrating his proficiency in this demanding medium. Recognizing the need for a dedicated organization to promote the art form, Vibert became a driving force behind the founding of the Société des Aquarellistes Français (Society of French Watercolorists) in 1879. He served as its first president, a position that underscored his commitment to the medium and his leadership role within the artistic community. The Society aimed to hold regular exhibitions and maintain high standards for watercolor art, contributing significantly to its appreciation in France. His involvement highlights his versatility and his engagement with different facets of the art world.

Vibert's creative energies were not confined to the visual arts. He also possessed considerable talent as a writer, particularly for the theatre. He authored several comedies and vaudeville pieces, often characterized by the same wit and satirical observation found in his paintings. Some sources suggest collaborations or close association with the popular actress Marie Lloyd, whom he married (though they later divorced in 1887). His theatrical work provided another outlet for his commentary on contemporary manners and society.

Furthermore, he contributed articles on art and painting techniques to publications like the influential Century Magazine, reaching an international audience. There are also mentions of his involvement in architecture, although specific projects may be less documented. This remarkable range of activities – painter in oil and watercolor, sculptor, playwright, author, inventor, and potentially architect – paints a picture of a true Renaissance man of the late nineteenth century, driven by a broad intellectual curiosity and creative impulse.

International Acclaim and the American Market

Jehan Georges Vibert achieved considerable fame and commercial success not only in France but also internationally, particularly in the United States. During the latter half of the nineteenth century, wealthy American collectors, often newly minted industrial tycoons, developed a strong appetite for contemporary European art, especially French Academic painting. Artists like Vibert, Jean-Léon Gérôme, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, and Alexandre Cabanel found a lucrative market across the Atlantic.

Vibert's witty depictions of cardinals proved especially popular with American buyers. The combination of exquisite technique, accessible subject matter, and gentle humour appealed to collectors seeking works that were both sophisticated and entertaining. Prominent families, such as the Vanderbilts, acquired his paintings. The high prices his works commanded at auction and through dealers like Goupil & Cie (who also represented Gérôme and Bouguereau) or Knoedler testified to his market appeal. His paintings became status symbols, adorning the mansions of the Gilded Age elite.

This American enthusiasm meant that a significant number of Vibert's major works quickly left France. Today, many important examples of his paintings can be found in the collections of major American museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (which holds works like The Missionary's Adventures and Palm Sunday in Spain) and the Art Institute of Chicago. His work La Reprimande entered the Met as part of the significant Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection bequest in 1887.

The popularity of Vibert and his Academic contemporaries in America stood in contrast to the slower acceptance of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism by mainstream collectors, although pioneering American collectors were beginning to acquire works by artists like Edgar Degas and Mary Cassatt. Vibert's success highlights the prevailing tastes of the era's establishment collectors, who often favoured narrative clarity, high finish, and recognizable subject matter over the radical formal innovations of the avant-garde. His international reputation solidified his status as a leading figure of the established art world of his time.

Collaborations and Artistic Circles

Throughout his career, Vibert interacted with numerous other artists, both as a student, a collaborator, and a prominent member of the Parisian art establishment. His training placed him in the studios of Félix-Joseph Barrias and François-Édouard Picot, connecting him to the lineage of French Academic painting. His time at the École des Beaux-Arts would have brought him into contact with many aspiring artists who later achieved recognition, such as Léon Bonnat and Jean-Jacques Henner.

His collaboration with the Spanish painter Eduardo Zamacois y Zabala on Entrée des Toreros (1866) demonstrates his connection to the circle of artists interested in Spanish themes, a popular trend in French art partly fueled by the work of Mariano Fortuny. This collaboration highlights the international exchanges occurring within the Paris art scene.

A more complex interaction involved the project for The Apotheosis of Thiers, a painting commemorating Adolphe Thiers, a prominent French statesman. Vibert initially collaborated on this large-scale work with the renowned military painter Édouard Detaille. However, Detaille reportedly withdrew from the project due to disagreements involving another highly respected Academic master, Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, who was perhaps also considered for or involved in the commission. Undeterred, Vibert decided to complete the ambitious painting on his own, showcasing his determination and confidence in handling major historical subjects, even though he was more famous for smaller genre scenes.

As the founder and first president of the Société des Aquarellistes Français, Vibert was central to a circle dedicated to that medium. His position within the broader Academic system, cemented by his Salon medals and Légion d'Honneur, placed him among the established figures of the art world, alongside painters like Gérôme, Bouguereau, Cabanel, and perhaps genre painters like Alfred Stevens or James Tissot, whose depictions of contemporary life, though different in subject, shared a commitment to technical finish. While his satirical bent set him apart, his adherence to Academic technique kept him firmly within its orbit, distinct from the Impressionists and other avant-garde movements challenging the Salon system.

Later Life and Legacy

Jehan Georges Vibert continued to paint and remain active in the art world into the early twentieth century. His satirical paintings of clergy remained popular, and he maintained his reputation for technical excellence. His divorce from Marie Lloyd in 1887 marked a personal change, but his professional life continued steadily. He continued exhibiting and fulfilling commissions, enjoying the fruits of a successful career built over decades.

He passed away in Paris on July 28, 1902, at the age of 61. At the time of his death, he was a well-respected and highly successful artist, recognized by the state and sought after by collectors. His legacy, however, became subject to the shifting tides of art history. The rise of Modernism in the early twentieth century led to a decline in the critical appreciation of Academic art in general. Artists like Vibert, once celebrated, were often dismissed by later critics as merely illustrative or anecdotal, lacking the formal innovation and perceived seriousness of the avant-garde.

However, in recent decades, there has been a renewed interest in nineteenth-century Academic art, prompting a re-evaluation of figures like Vibert. Art historians now recognize the high level of technical skill involved in his work and appreciate his paintings as valuable documents of the social attitudes, tastes, and humour of his time. His unique niche – the satirical Cardinal Painting – is acknowledged as a distinct contribution to genre painting. While perhaps not considered a revolutionary figure in the mold of the Impressionists, his work offers a fascinating window into the complexities of the late nineteenth-century art world.

His paintings continue to be enjoyed by museum visitors for their narrative detail, humour, and visual appeal. The controversies surrounding his satirical treatment of the church are now viewed more as historical context than as a serious challenge to his artistic merit. He remains significant as a master technician, an innovator in art materials, a multi-talented creative force, and the preeminent painter of witty clerical genre scenes in the French Academic tradition.

Conclusion

Jehan Georges Vibert navigated the competitive art world of nineteenth-century Paris with skill, ambition, and a distinctive sense of humour. Rooted in the Academic tradition through his training under masters like Picot and Barrias and his success at the Salon, he developed a unique and immensely popular specialty: the satirical depiction of Catholic cardinals and clergy. These works, characterized by meticulous detail, vibrant colour (including his signature "Vibert Red"), and gentle wit, captured the public imagination in France and, notably, America, securing his financial success and international reputation alongside contemporaries like Gérôme and Bouguereau.

His service in the Franco-Prussian War and subsequent award of the Légion d'Honneur added to his public stature. Beyond his famous oil paintings, Vibert demonstrated remarkable versatility as a master watercolorist, founder and president of the Société des Aquarellistes Français, a playwright, author on art techniques, and inventor of artists' materials. While his fame waned somewhat with the rise of Modernism, recent art historical reassessment acknowledges his exceptional technical skill and his unique contribution to genre painting. Vibert remains a compelling figure, embodying both the high craft of the Academic tradition and a sharp, observant eye for the human comedy within the institutions of his time.