Katsushika Hokusai stands as one of the towering figures in Japanese art history, a master of the ukiyo-e style whose influence extended far beyond the shores of his native land. Living and working during Japan's Edo period (1603-1868), a time of relative peace and burgeoning urban culture, Hokusai captured the spirit of his age with unparalleled energy and innovation. His prolific output, most famously exemplified by the print series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, not only delighted his contemporaries but also profoundly impacted the course of Western art, particularly Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. His life was one of relentless dedication to his craft, marked by constant evolution and an insatiable curiosity about the world around him.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Born in 1760 in the Katsushika district of Edo (modern-day Tokyo), the man the world would come to know as Hokusai was initially named Tokitarō. His parentage remains somewhat uncertain, though it's believed he may have been the son of a mirror maker for the Shogun's court. Regardless of his origins, a passion for drawing emerged early. By the age of six, he was already sketching, demonstrating a natural inclination towards the visual arts that would define his long life.

His formal artistic training began indirectly. Around the age of twelve, he worked at a lending library, exposing him to woodblock-printed books. At fourteen, he became an apprentice to a wood-carver, learning the intricate skills required to cut the blocks used in the printing process. This hands-on experience with the medium would prove invaluable later in his career as a print designer. It gave him a deep understanding of the technical possibilities and limitations of woodblock printing.

The pivotal moment in his early career came at the age of eighteen (around 1778), when he entered the studio of Katsukawa Shunshō. Shunshō was a leading figure in the ukiyo-e world, particularly known for his realistic portraits of Kabuki actors. Ukiyo-e, meaning "pictures of the floating world," was a genre that depicted the transient pleasures and urban life of Edo – Kabuki actors, beautiful courtesans, sumo wrestlers, historical scenes, and eventually, landscapes. Under Shunshō's tutelage, the young artist learned the conventions of the Katsukawa school and began producing prints, primarily focused on actor portraits and illustrations for popular fiction (kibyōshi).

Developing an Independent Style (The Sōri Period)

Hokusai's time in the Katsukawa school was formative, but his restless spirit and desire for broader artistic exploration eventually led to friction. He began studying the styles of other schools, including the Kanō school (known for its Chinese-influenced ink painting) and the Tawaraya school (associated with the decorative Rinpa style, notably through artists like Tawaraya Sōtatsu and later Ogata Kōrin). He also encountered European art, likely through Dutch copperplate engravings imported via the trading post at Nagasaki, which introduced him to concepts like linear perspective and shading, uncommon in traditional Japanese painting.

Around 1793, Hokusai left the Katsukawa school, possibly expelled due to his exploration of rival styles. This marked the beginning of his independent career and a period of significant artistic experimentation. He adopted various art names (gō), a common practice for Japanese artists, often signifying shifts in style or life circumstances. One of the earliest prominent names he used during this independent phase was "Sōri," borrowed from the Tawaraya school.

During the "Sōri period," Hokusai moved away from the actor prints that dominated his early work. He focused more on surimono (privately commissioned prints, often featuring poetry and luxurious printing techniques) and book illustrations. He experimented with different themes and techniques, gradually forging a style distinct from his teacher, Shunshō. His work began showing a greater dynamism and a broader range of subjects, hinting at the versatility that would become his hallmark. This period laid the groundwork for his later, more famous innovations.

The Peak Years: Landscapes and Innovation

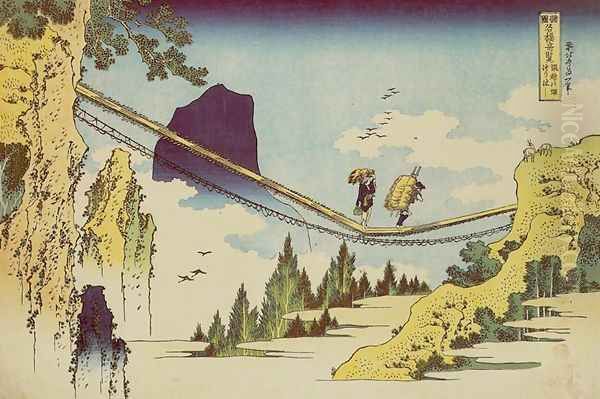

The early 19th century saw Hokusai enter his most productive and innovative phase, solidifying his reputation. He continued to use various names, including "Katsushika Hokusai," the name by which he is most widely known today. His fame grew through his book illustrations and individual prints, but it was his revolutionary approach to landscape that truly set him apart. While landscapes had appeared in ukiyo-e before, they were often secondary elements. Hokusai elevated landscape to a major subject in its own right.

![Kanagawa Oki Nami Ura [under The

Great Wave Off Kanagawa], From The Series Fugaku Sanjurokkei by Katsushika Hokusai](https://www.niceartgallery.com/imgs/2335269/m/katsushika-hokusai-kanagawa-oki-nami-ura-under-the-great-wave-off-kanagawa-from-the-series-fugaku-sanjurokkei-510202a7.jpg)

His growing interest in Western artistic conventions became more apparent. He skillfully integrated elements like perspective and atmospheric effects into his compositions, blending them seamlessly with traditional Japanese aesthetics. This fusion created works that felt both familiar and strikingly new to his audience. He became particularly known for his dynamic compositions and his innovative use of color, including the newly available synthetic pigment, Prussian blue (bero-ai), which offered a vibrant and stable hue perfect for depicting water and sky.

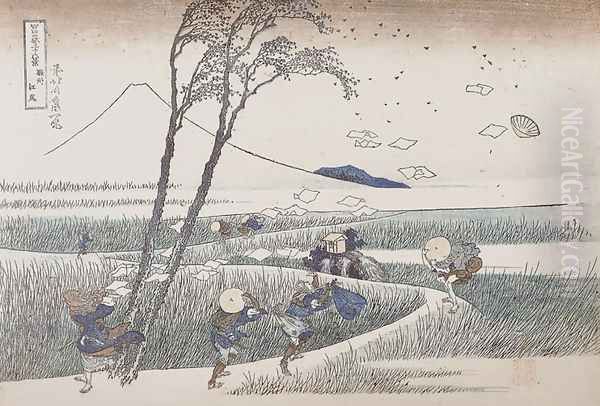

The culmination of this period was the iconic series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku Sanjūrokkei), published between roughly 1830 and 1833. Mount Fuji, Japan's highest and most sacred peak, had long been a subject in Japanese art, but Hokusai approached it with unprecedented creativity. The series depicted the mountain from various locations, in different seasons, and under diverse weather conditions, showcasing its enduring presence in the landscape and the lives of ordinary people. Despite the title, the immense popularity of the series led to the addition of ten supplementary prints, bringing the total to forty-six.

Within this series are some of the most famous images in global art history. The Great Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa-oki Nami Ura) is perhaps the single most recognizable Japanese artwork worldwide, a breathtaking depiction of a colossal wave threatening fishing boats, with Mount Fuji serene in the distance. Other masterpieces from the series include Fine Wind, Clear Morning (Gaifū Kaisei), also known as Red Fuji, capturing the mountain bathed in the reddish light of dawn, and Rainstorm Beneath the Summit (Sanka Hakuu), a dramatic portrayal of a storm swirling around the mountain's base. These works demonstrated Hokusai's mastery of composition, color, and dramatic effect.

The Prolific Hokusai Manga

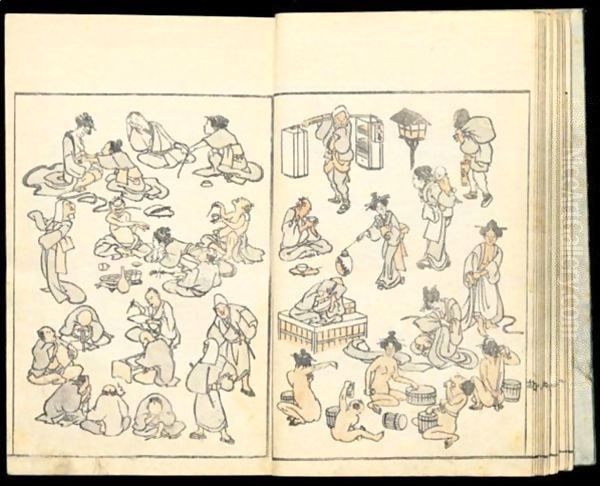

Alongside his famous landscape series, Hokusai produced another monumental work: the Hokusai Manga (Hokusai's Sketches). This collection, published in fifteen volumes between 1814 and 1878 (the last three posthumously), is a vast encyclopedia of images drawn from Hokusai's keen observation and boundless imagination. It was not a narrative manga in the modern sense but rather a collection of sketches intended partly as a drawing manual for students and a sourcebook for other artists and craftsmen.

The Manga contains thousands of individual drawings covering an astonishing range of subjects: realistic depictions of people from all walks of life, animals (both real and mythical), plants, landscapes, architecture, historical and legendary figures, ghosts, and everyday objects. The sketches vary from quick, energetic studies to more detailed renderings. They showcase Hokusai's incredible draftsmanship, his wit, his deep understanding of form and movement, and his fascination with capturing the essence of virtually everything he saw or imagined.

The Hokusai Manga was immensely popular during his lifetime and played a significant role in spreading his fame. It provided a window into the artist's mind and working methods. While not directly related to contemporary manga narratives, Hokusai's use of the term "manga" (meaning "random sketches" or "impromptu drawings") and the sheer visual energy and storytelling potential within the sketches have led some to consider him a distant ancestor of modern Japanese comics and animation. The collection remains a treasure trove for understanding Edo period life and Hokusai's artistic genius.

Later Life and Enduring Passion (Gakyō Rōjin Manji)

Hokusai's artistic drive remained undiminished throughout his long life. Even in his later years, facing personal hardships including the death of his second wife, financial difficulties (reportedly exacerbated by a grandson's gambling debts), and a fire that destroyed his studio and much of his work in 1839, he continued to create with remarkable vigor. He moved frequently – legend claims he relocated over ninety times during his life, partly because he disliked cleaning and would simply move once a place became too messy.

In his seventies and eighties, Hokusai increasingly focused on nikuhitsu-ga – original paintings executed by brush directly onto paper or silk, as opposed to designs for woodblock prints. These later paintings often display a heightened sense of spiritual depth and an even greater refinement of brushwork. He also produced another significant print series, One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku Hyakkei), published in three volumes starting in 1834. This series, executed primarily in black and grey, offered further explorations of Japan's iconic mountain, often with more experimental and intimate compositions than the earlier Thirty-six Views.

During this late phase, he often signed his work "Gakyō Rōjin Manji," which translates to "The Old Man Mad About Painting." This name reflected his obsessive dedication to his art. In the preface to One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji, he famously wrote about his artistic development, stating that nothing he had produced before the age of seventy was of much account, and that only by the age of one hundred might he achieve a truly divine understanding of art, hoping to live even longer to perfect his craft. He continued painting almost until his death in 1849 at the age of eighty-nine (ninety by traditional East Asian age reckoning). His purported last words were a wish for just five or ten more years to become a "real painter."

Artistic Style and Techniques

![Fugaku Hyakkei [one Hundred Views Of Mount Fuji] by Katsushika Hokusai](https://www.niceartgallery.com/imgs/2335178/m/katsushika-hokusai-fugaku-hyakkei-one-hundred-views-of-mount-fuji-98993b5a.jpg)

Hokusai's style is characterized by its energy, dynamism, and observational acuity. He possessed an extraordinary ability to capture movement – the crashing of a wave, the flutter of a bird's wings, the gestures of working people. His compositions are often bold and unconventional, utilizing dramatic cropping, unusual perspectives, and strong diagonal lines to create visual excitement. He masterfully balanced detail and simplification, knowing precisely what to include and what to omit for maximum impact.

His line work is renowned for its confidence and fluidity, whether in the quick sketches of the Manga or the refined outlines of his print designs and paintings. He was a superb colorist, particularly adept at using the vibrant new blues available to him, but also skilled in creating subtle harmonies and dramatic contrasts. His ability to blend traditional Japanese artistic sensibilities (drawing from schools like Katsukawa, Kanō, and Rinpa) with elements absorbed from Western art (perspective, shading, realism) resulted in a unique and powerful visual language.

Above all, Hokusai's art reflects a profound engagement with the world around him. He depicted the grandeur of nature, particularly the overwhelming power of the sea and the enduring presence of Mount Fuji, but he was equally fascinated by the human element. His works teem with life, showing farmers, fishermen, travelers, artisans, and townspeople engaged in their daily activities, often with humor and empathy. This deep connection to both nature and humanity gives his art its enduring appeal.

Hokusai and His Contemporaries

Throughout his long career, Hokusai interacted with numerous other artists, writers, and publishers who shaped the cultural landscape of Edo. His initial training under Katsukawa Shunshō provided his foundation in ukiyo-e. While he eventually diverged from the Katsukawa style, the discipline learned there was crucial. His exploration of other styles brought him into contact, at least intellectually, with the legacies of masters like Ogata Kōrin of the Rinpa school, whose decorative flair and stylized nature depictions can sometimes be sensed in Hokusai's work.

He collaborated frequently with writers and poets, illustrating novels and poetry collections. A significant collaborator was the popular novelist Takizawa Bakin (also known as Kyokutei Bakin). They worked together on several projects, such as the illustrated novel Chinsetsu Yumiharizuki (Strange Tales of the Crescent Moon), although their relationship was reportedly sometimes contentious due to artistic differences. Hokusai also associated with the writer Ryūtei Tanehiko.

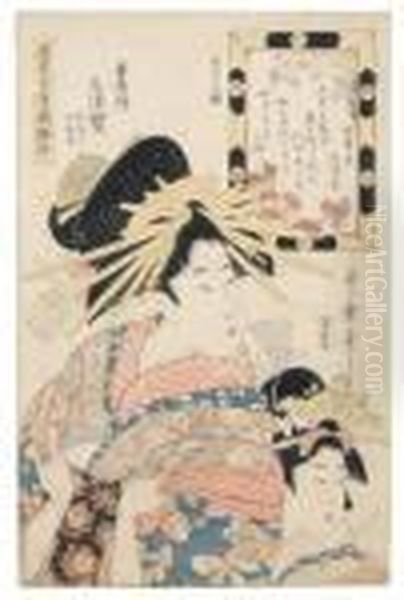

Within the ukiyo-e world, Hokusai was a contemporary of other major artists. Kitagawa Utamaro, famous for his elegant portraits of beautiful women (bijin-ga), was active during Hokusai's earlier independent period. While their primary subjects differed, they were both leading figures pushing the boundaries of print design. Tōshūsai Sharaku, known for his intense and psychologically penetrating actor portraits produced during a brief, mysterious period (1794-95), was another contemporary whose bold expressiveness resonated within the ukiyo-e scene Hokusai inhabited.

Later in Hokusai's career, Utagawa Hiroshige emerged as another great master of the ukiyo-e landscape print. Hiroshige's style, often characterized by its more lyrical and atmospheric quality, provides a fascinating contrast to Hokusai's dramatic dynamism. While sometimes seen as rivals, particularly in the landscape genre, records indicate they had some contact. Another contemporary ukiyo-e artist, Keisai Eisen, known for his decadent bijin-ga, acknowledged Hokusai's skill in his writings. These interactions, collaborations, and rivalries fueled the vibrant artistic environment of Edo.

The Enduring Legacy: Influence in Japan

Within Japan, Hokusai's impact was immediate and lasting. His elevation of landscape painting within the ukiyo-e genre broadened its scope and appeal. His technical innovations, particularly his use of color and perspective, influenced subsequent generations of print artists. The Hokusai Manga served as an invaluable resource for countless artists and craftspeople, disseminating his style and observational approach widely.

While ukiyo-e as a dominant art form declined with the Meiji Restoration (1868) and the influx of Western culture, Hokusai's reputation endured. He came to be seen as one of the quintessential Japanese artists, embodying a unique blend of technical mastery, imaginative power, and deep connection to Japanese culture and landscape. His influence can be traced in the development of modern Japanese painting (Nihonga) and, as mentioned, his work is often cited as a precursor to the visual dynamism found in modern manga and anime. Today, his works are celebrated in Japanese museums and remain potent symbols of national artistic heritage.

Global Impact: Hokusai and the West

Hokusai's most dramatic influence, however, occurred in the West. Following the reopening of Japan to international trade in the mid-19th century, Japanese art objects, including ukiyo-e prints, began flowing into Europe and America. These prints, often initially used as packing material for porcelain, captivated Western artists who were seeking new modes of expression beyond the constraints of academic tradition. This fascination with Japanese art became known as Japonisme.

Hokusai's work, particularly Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji and the Hokusai Manga, was central to this phenomenon. Artists associated with Impressionism and Post-Impressionism were especially drawn to his bold compositions, flattened perspectives, decorative use of color, asymmetrical arrangements, and everyday subject matter. Claude Monet, for instance, collected Japanese prints and his famous water lily paintings show compositional echoes of Japanese art. Edgar Degas admired Hokusai's ability to capture fleeting moments and unconventional viewpoints, which resonated with his own depictions of dancers and modern life.

Vincent van Gogh was deeply affected by Japanese prints, copying works by Hiroshige and incorporating stylistic elements – strong outlines, flat areas of color – into his own paintings like Starry Night. Mary Cassatt, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Édouard Manet, and Paul Gauguin were among the many others who collected or were inspired by Japanese prints, with Hokusai being a key figure. They saw in his work a freshness, directness, and decorative sophistication that offered an alternative to Western realism. The Great Wave became, and remains, an icon not just of Japanese art, but of global visual culture, endlessly reproduced and reinterpreted.

Hokusai's Eccentricities

Beyond his artistic achievements, Hokusai was known for his eccentric personality. His frequent name changes – using over thirty different art names throughout his life – reflected not only artistic shifts but perhaps also a restless, unconventional nature. Each name often corresponded to a distinct phase in his artistic output and personal life.

His legendary habit of moving house frequently (allegedly 93 times) is often attributed to his untidiness. Stories suggest he would let clutter and debris accumulate until his living space became unbearable, at which point he would simply pack up his essential drawing tools and find a new dwelling, leaving the mess behind. While perhaps exaggerated, this anecdote paints a picture of an artist utterly consumed by his work, with little patience for domestic chores or conventional living. These quirks contribute to the image of Hokusai as the single-minded "Old Man Mad About Painting."

Conclusion

Katsushika Hokusai's life spanned nearly nine decades, a period of immense social and cultural change in Japan. Through it all, he remained steadfastly devoted to his art, constantly learning, experimenting, and producing an astonishing volume of work. From his early days as an apprentice to his final years as the revered "Gakyō Rōjin Manji," his career was a journey of relentless artistic exploration.

He mastered the ukiyo-e tradition, pushing its boundaries, particularly in the realm of landscape, and created images like The Great Wave off Kanagawa that have achieved universal recognition. His influence extended far beyond Japan, playing a crucial role in shaping the development of modern Western art. Hokusai stands as a testament to the power of artistic dedication, keen observation, and the ability to bridge cultures through the universal language of visual expression. His legacy continues to inspire and fascinate audiences worldwide, securing his place as one of history's most significant and beloved artists.