Jesse Jewhurst Hilder, an artist whose name resonates with a particular poignancy in the annals of Australian art, carved a unique niche for himself in the early 20th century. Though his career was tragically brief, spanning little more than a decade from roughly 1904 until his untimely death in 1916, Hilder's contribution, particularly in the medium of watercolour, remains significant. He was an artist who captured the subtle moods and ephemeral beauty of the Australian landscape with a distinctive, lyrical quality, often imbued with a romantic sensibility. His works, celebrated for their purity of colour, transparency, and atmospheric depth, offer a window into a soul that perceived beauty in the everyday and the unassuming.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Toowoomba, Queensland, in 1881, Jesse Jewhurst Hilder’s early life was marked by a move to Brisbane and subsequently to various locations, eventually finding a base in New South Wales. Unlike many of his contemporaries who benefited from formal academic training in established art schools either in Australia or abroad, Hilder was largely self-taught. His artistic inclinations manifested early, and he honed his skills through diligent practice, often sketching and painting during weekends, sometimes in the company of friends who shared his passion.

This path of self-instruction, while perhaps presenting its own set of challenges, also allowed Hilder to develop a highly personal and unadulterated style. He was not heavily constrained by the prevailing academic conventions of the time, which often dictated subject matter and technique. Instead, Hilder's approach was more intuitive, driven by his direct response to the landscapes he encountered and his innate understanding of the watercolour medium. His formative years involved working in a bank, a profession that provided financial stability but likely contrasted sharply with his artistic aspirations. The discipline and meticulousness required in banking, however, may have inadvertently contributed to the precision and careful consideration evident in his art.

The Essence of Hilder's Style: Watercolour Mastery

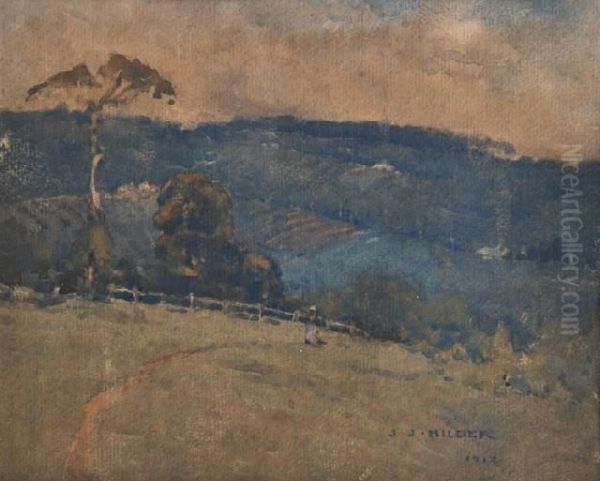

The hallmark of Jesse Jewhurst Hilder's art lies in his exquisite handling of watercolour. He achieved a remarkable purity and transparency in his washes, allowing the white of the paper to shine through and contribute to the luminosity of his scenes. This technique, often involving wet-on-wet applications, created soft, diffused edges and a sense of atmospheric haze that became characteristic of his work. His palette, while capable of vibrant hues, often leaned towards subtle, harmonious tonal arrangements, capturing the delicate play of light and shadow.

Hilder's style has been described as romantic, and indeed, there is a poetic, almost dreamlike quality to many of his landscapes. He was less concerned with a literal, topographical rendering of a scene and more interested in evoking its mood and essence. This romanticism was not of the grandiose, sublime variety often associated with earlier landscape traditions, but a more intimate and personal response to the quiet beauty of the Australian bush and its settled corners. Artists like the French Barbizon School painter Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, known for his atmospheric landscapes and tonal subtleties, are often cited as potential, if indirect, influences, sharing a similar poetic sensibility.

His technical proficiency allowed him to manipulate the watercolour medium to achieve effects that were both delicate and strong. He understood the importance of composition, often employing simple yet effective arrangements that draw the viewer into the scene. The scale of his works was generally modest, yet they possess an intensity and completeness that belies their physical dimensions. This focus on smaller formats may have been partly due to the practicalities of working en plein air or the constraints of his health, but it also lent an intimacy to his art.

Themes and Subjects: A Personal Vision of Australia

While Hilder painted the Australian landscape, his choice of subjects often veered away from the heroic or overtly picturesque. He found beauty in the commonplace: a quiet stretch of creek, a cluster of rural cottages, the silhouette of trees against a twilight sky, or even more industrial subjects like clay pits and brick kilns. This ability to find artistic merit in the less celebrated aspects of the landscape set him apart and demonstrated a unique vision. His works were not grand national statements in the vein of some earlier Heidelberg School painters like Arthur Streeton or Tom Roberts, but more personal, introspective meditations on place.

His early works sometimes featured brighter colours, but as his style matured, and perhaps as his health declined, he increasingly favoured more muted, tonal compositions, often exploring the subtle gradations of a single dominant colour. This approach enhanced the atmospheric qualities of his paintings, imbuing them with a sense of quietude and sometimes melancholy. Works depicting dawn, dusk, or overcast days allowed him to explore these nuanced light effects to their fullest. He was a master of capturing the "spirit of place," conveying not just what a location looked like, but how it felt.

The human presence in Hilder's landscapes is often understated, suggested by a distant cottage, a fence line, or a gently smoking chimney. This subtlety prevents the figures or structures from dominating the natural setting, instead integrating them harmoniously within the broader environment. This approach aligns with a romantic sensibility where nature remains the primary focus, with human elements serving to contextualize or add a touch of poignancy.

A Catalogue of Notable Works

Several works stand out in Jesse Jewhurst Hilder’s oeuvre, each exemplifying different facets of his artistic talent.

"Lennox Bridge" (1911) is one of his most celebrated watercolours. Depicting the historic single-arch stone bridge over the Parramatta River, this work showcases Hilder's ability to combine structural accuracy with atmospheric softness. The rendering of the stonework is precise, yet the surrounding foliage and the reflections in the water are handled with a delicate touch, creating a scene of tranquil beauty. The interplay of light and shadow, and the subtle colour harmonies, are masterfully executed. This work is held in high esteem and can be found in collections such as the Logan Art Collection and the Art Gallery of South Australia.

"Dora Creek" (1916) holds a particularly poignant place in his body of work, as it is reputed to be the last painting he completed, just weeks before his death. This work, likely "Morning at Dora Creek," captures a serene waterscape, possibly at dawn or dusk, with Hilder's characteristic misty atmosphere and gentle colour transitions. It embodies the quiet lyricism that defines his mature style and serves as a touching final statement from the artist. The National Gallery of Victoria is a key institution holding works like this.

"The Clay Pit" (c. 1913) demonstrates Hilder's interest in less conventional landscape subjects. Instead of an idyllic pastoral scene, he portrays an active industrial site. Yet, even here, Hilder finds a certain beauty in the raw earth tones, the forms carved out by excavation, and the atmospheric conditions. This work highlights his ability to transform the mundane into the picturesque through his artistic vision and technical skill. It is noted as being in the collection of Mr. Bim Hildreth and also listed with the National Gallery of Victoria.

Other significant pieces include "Ploughing" (1910), which captures a rural scene with a sense of timelessness, held by the Art Gallery of South Australia (formerly in the Alex Melrose collection). "The Three Barrows" (1914), a smaller, intimate piece, likely showcasing his skill in composition and tonal control, is associated with the John and Mrs. S.H. Hope Collection and Mr. Bim Hildreth. "The Deviation" (1913), another work held by the National Gallery of Victoria and the Art Gallery of South Australia, likely explores a man-altered landscape, perhaps a road or railway cutting, again revealing Hilder's capacity to find artistic subjects in varied environments.

His earlier works, such as "Ploughing and Pastoral Scenes" (1902) and "Fast Falling Eventide" (1902), indicate his early engagement with rural themes and atmospheric effects. Later pieces like "The Cross Roads" (1910), "Landscape Near Carlingford" (1910), "The Silent Hour" (1925 - likely a posthumous titling or exhibition date), "Afternoon Landscape, Homebush" (1925 - as above), and "Grey Landscape, Hazelbrook" (1925 - as above) further illustrate his dedication to capturing the nuanced beauty of the Australian landscape. Even titles like "The Plough" (1961 - likely an exhibition or acquisition date for an earlier work) and "The Oak Tree" (1961 - as above) suggest his enduring connection to these pastoral and natural motifs.

The Shadow of Illness and a Premature End

A crucial aspect of Jesse Jewhurst Hilder's story is his lifelong battle with ill health. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1906, a devastating illness at the time with limited treatment options. For the remainder of his short life, Hilder's health was precarious, fluctuating between periods of relative stability and severe decline. This constant struggle undoubtedly cast a shadow over his existence and, by extension, his art.

Some art historians suggest that his illness influenced his artistic output, perhaps contributing to the melancholic or introspective mood present in some of his later works. The urgency of a life lived under the threat of premature death may have also fuelled his artistic drive, compelling him to capture the beauty he saw around him. His emotional state, oscillating between hope and despair, is said to be subtly reflected in the shifting tones and atmospheres of his paintings. He passed away on April 10, 1916, at the young age of 34, cutting short a career that held immense promise.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Despite the brevity of his artistic career, Jesse Jewhurst Hilder left an indelible mark on Australian art. His watercolours were admired for their unique qualities even during his lifetime, and his reputation grew posthumously. Memorial exhibitions of his work were held, including a significant one in 1916 shortly after his death, organised by his friend and fellow artist Sydney Ure Smith, who also published a monograph, "J.J. Hilder, Watercolourist," which helped to cement Hilder's reputation. Another commemorative exhibition was held in 1966.

Hilder's influence extended to his own family. His son, Brett Hilder, became a notable watercolourist in his own right, continuing the family's artistic tradition. His nephew, Arthur Vernon "Bim" Hilder, pursued sculpture, indicating a broader artistic inclination within the family. Another nephew, the internationally renowned sculptor Clement Meadmore, also acknowledged an early awareness and appreciation of Hilder's art, suggesting that the emotional depth and artistic integrity of his uncle's work left a lasting impression.

Beyond his immediate circle, Hilder's distinctive approach to watercolour influenced other Australian artists who sought a more lyrical and personal interpretation of the landscape. His ability to convey mood and atmosphere with such economy of means provided an alternative to the more robust, sun-drenched visions of some of his contemporaries. Remarkably, his influence even reached artists in Southeast Asia; for instance, the Burmese painter Saya Saung is noted as having been inspired by Hilder's style, a testament to the universal appeal of his delicate artistry.

Hilder in the Context of His Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Hilder's contribution, it's useful to consider him within the broader context of Australian art at the turn of the 20th century. The dominant force in the preceding decades had been the Heidelberg School, with artists like Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, Charles Conder, and Frederick McCubbin, who championed plein air painting and a nationalistic interpretation of the Australian landscape, often focusing on its bright light and distinctive colours.

While Hilder also painted en plein air and focused on the Australian landscape, his approach was generally more intimate and poetic than the heroic naturalism of the Heidelberg pioneers. He shared with them a deep love for the Australian environment, but his interpretation was softer, more suffused with atmosphere and personal feeling.

Contemporaries who also made significant contributions to landscape painting included Hans Heysen, renowned for his majestic depictions of gum trees and the Flinders Ranges, whose work, while also deeply connected to the Australian light, often had a more monumental quality. Elioth Gruner, another contemporary, was celebrated for his lyrical landscapes, particularly his depictions of the morning mist and subtle light effects, sharing some common ground with Hilder in terms of poetic sensibility, though Gruner often worked in oils with a different textural quality.

Sydney Long developed a distinctive Art Nouveau-influenced style, often incorporating decorative, symbolic, and mythological elements into his landscapes, a different path from Hilder's more direct, though romanticised, naturalism. Blamire Young, another significant watercolourist of the period, was known for his atmospheric effects and often more dramatic compositions, sometimes with a narrative or historical bent.

The early modernists like Margaret Preston and Grace Cossington Smith were also beginning to emerge during Hilder's active years, pushing Australian art in new directions with their explorations of colour, form, and post-impressionist ideas. Hilder, however, remained more aligned with a romantic, tonalist tradition, though his work was far from derivative.

Internationally, the legacy of British watercolourists like J.M.W. Turner and John Sell Cotman had long established watercolour as a serious medium for landscape art. While Hilder's style was his own, he worked within this rich tradition. The atmospheric qualities in his work also bear a distant kinship with the tonalism of artists like James McNeill Whistler, who emphasized mood and harmony over precise detail. Rowland Hilder, a later British watercolourist (no direct relation, despite the surname), became famous for his depictions of the English countryside, particularly Kent, often in winter, sharing a similar dedication to the watercolour medium and landscape, though their styles and subjects differed significantly.

Jesse Jewhurst Hilder's unique position lies in his ability to synthesize his personal response to the Australian landscape with a masterful command of the watercolour medium, creating works that were both distinctly Australian and universally appealing in their gentle beauty. He was not a radical innovator in terms of avant-garde movements, but he was an artist of profound sensitivity and skill who refined a particular mode of landscape expression to a high degree of perfection.

Conclusion: The Quiet Brilliance of J.J. Hilder

Jesse Jewhurst Hilder's life was short, but his artistic legacy endures. He was a poet in paint, an artist who found profound beauty in the quiet corners of the Australian landscape and translated it into watercolours of exquisite delicacy and atmospheric depth. His work stands as a testament to the power of a personal vision and the expressive potential of the watercolour medium. While his contemporaries explored various facets of Australian identity and artistic innovation, Hilder offered a more introspective, lyrical interpretation that continues to resonate with viewers today. His paintings are not just depictions of places, but evocations of mood, light, and the fleeting moments of beauty that often go unnoticed. In the gallery of Australian art, J.J. Hilder occupies a special place, his luminous watercolours a quiet but persistent reminder of a brilliant talent taken too soon.