Introduction: A Leading Light in British Watercolour

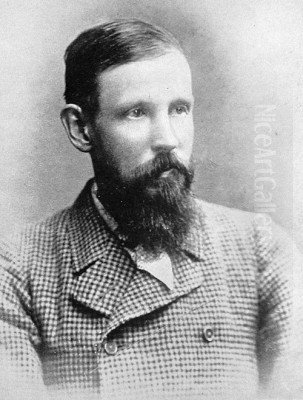

Thomas Collier, born in Glossop, Derbyshire in 1840, stands as one of the most highly regarded British landscape watercolourists of the later nineteenth century. Though his life was relatively short, ending in Hampstead, London, in 1891, his artistic output was significant and his influence considerable. Working primarily in watercolour, Collier developed a distinctive and powerful style characterized by its breadth, directness, and remarkable ability to capture the fleeting effects of light and weather across the British landscape. He eschewed the detailed finish favoured by many contemporaries, instead pursuing a vigorous, almost impressionistic approach that conveyed the mood and atmosphere of open spaces, particularly moorlands, coastal scenes, and heathlands. His work represents a vital link in the great tradition of British watercolour painting, drawing inspiration from earlier masters while forging a path that resonated with emerging naturalist and atmospheric sensibilities.

Collier's dedication to his chosen medium and his profound connection with the natural world allowed him to produce works of enduring freshness and vitality. He was largely self-taught, honing his skills through direct observation and a deep study of nature itself, alongside an appreciation for the giants of watercolour who preceded him. His paintings are not mere topographical records; they are evocative expressions of the spirit of place, rendered with a confidence and economy of means that continues to impress artists and collectors alike. His reputation, high during his lifetime, has endured, cementing his position as a key figure in the landscape art of Victorian Britain.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Thomas Collier's journey into the world of art was not one marked by formal academic training in the conventional sense. Born into a family with connections to the hatting industry in Derbyshire, his early life provided little indication of the artistic heights he would later achieve. Unlike many artists of his generation who passed through the Royal Academy Schools or other established institutions, Collier's artistic education appears to have been largely a matter of personal inclination and diligent self-study. This independence from academic constraints may well have contributed to the freshness and individuality that characterize his mature style.

It is believed that Collier received some rudimentary instruction in painting, possibly locally, but the most significant forces shaping his artistic vision were the landscapes themselves and the work of earlier British watercolour masters. He spent considerable time outdoors, sketching directly from nature, developing an intimate understanding of the forms, colours, and changing conditions of the British countryside. This practice of plein air painting, while not unique to Collier, was central to his method and allowed him to capture the immediacy and atmospheric truth that define his best work.

He deeply admired and studied the works of artists like David Cox (1783-1859) and Peter De Wint (1784-1849). From Cox, he likely absorbed lessons in capturing movement, weather, and the textures of rugged landscapes using broad, expressive brushwork. De Wint's influence might be seen in Collier's handling of wide, panoramic views and his mastery of transparent washes to convey light and space. While acknowledging these influences, Collier synthesized them into a style entirely his own, marked by an even greater degree of boldness and atmospheric suggestion than often seen in his predecessors. His early development was a process of absorption, observation, and relentless practice.

The Emergence of a Distinctive Style

By the 1860s, Thomas Collier began to exhibit his work and establish his reputation. His style rapidly matured into one that was instantly recognizable for its vigour and atmospheric power. Central to his approach was the watercolour medium itself, which he handled with exceptional skill and confidence. He favoured broad, wet washes of transparent colour, laid down quickly and decisively, often allowing colours to blend on the paper to create subtle gradations of tone and hue. This technique was perfectly suited to capturing the transient effects of light breaking through clouds, the dampness of a moor after rain, or the breezy expanse of a coastal common.

Collier avoided the meticulous detail and high finish that characterized much popular Victorian art, particularly the works associated with Pre-Raphaelite landscape or the charming, detailed watercolours of artists like Myles Birket Foster (1825-1899). Instead, Collier focused on the overall impression, the 'big look' of the landscape. His brushwork could be bold and almost abstract in close examination, yet resolved into a convincing representation of reality when viewed from a slight distance. This economy of means, where every brushstroke served a purpose in conveying form, light, or atmosphere, was a hallmark of his genius.

His colour palette was often restrained, favouring earthy tones, subtle greys, blues, and greens that accurately reflected the typical conditions of the British landscape he loved. However, he could also employ brighter accents effectively to capture shafts of sunlight or the specific colours of heather in bloom or autumn foliage. The interplay of light and shadow was crucial, rendered not through harsh contrasts but through nuanced tonal relationships achieved with masterful control of wash transparency. This direct, suggestive, and atmospheric style set him apart and positioned him as a leading figure among the more progressive landscape painters of his time.

Subject Matter: The Soul of the British Landscape

Thomas Collier's primary subject was the untamed or semi-tamed landscape of Great Britain. He was particularly drawn to wide, open spaces where the sky played a dominant role and the effects of weather were most apparent. The moorlands of Yorkshire, Derbyshire, and North Wales were frequent subjects, their rolling contours, rough textures, and dramatic skies providing ample scope for his expressive technique. He captured the loneliness and grandeur of these places, often depicting vast expanses under changeable skies, conveying a sense of elemental power and natural freedom.

Coastal scenes, especially those of East Anglia (like Walberswick and Southwold) and the Sussex coast, also featured prominently in his oeuvre. He excelled at painting estuaries, beaches, and harbours, capturing the unique light and atmosphere of the seaside. Works like Walberswick Pier demonstrate his ability to render the interplay of water, sky, and man-made structures with characteristic breadth and atmospheric sensitivity. The flat, expansive landscapes of East Anglia, with their huge skies, offered a different kind of challenge and inspiration compared to the rugged moors.

The South Downs in Sussex were another favourite location, providing subjects for numerous watercolours. He captured the distinctive chalk hills, the patterns of fields, and the feeling of spaciousness under sweeping skies. Works titled A Sussex Common or The South Downs are typical, focusing on the essential character of the landscape rather than specific landmarks. Throughout his work, there is a consistent feeling of authenticity, born from direct observation and a deep empathy with the spirit of the place. He rarely included prominent figures, and when figures or animals appear, they are typically small elements within the larger landscape, emphasizing the dominance of nature.

Technique and Watercolour Mastery

Collier's technical prowess in watercolour was exceptional. He understood the medium's unique properties – its transparency, fluidity, and luminosity – and exploited them to the full. His method often involved working on damp paper, allowing colours to fuse softly at the edges, creating atmospheric effects and suggesting distance. This 'wet-in-wet' technique, combined with drier, more defined brushstrokes for foreground details or specific textures, gave his work both softness and structure.

He was known for his directness. There is often a sense of immediacy and spontaneity in his watercolours, suggesting they were painted quickly, capturing a fleeting moment en plein air. While he undoubtedly worked on compositions in the studio, the foundation of his art lay in outdoor sketching and painting. This commitment to working directly from nature aligns him with the broader Naturalist movement gaining traction in Europe during the later nineteenth century, although his style remained distinctly personal and rooted in the British watercolour tradition.

His use of paper texture was also important. He often worked on fairly rough-textured paper, which helped to break up the washes and add sparkle and texture to the surface, enhancing the sense of light and air. He was economical with his brushstrokes, achieving maximum effect with minimum fuss. Unlike artists who built up layers of intricate detail, Collier suggested form and texture through bold placement of tone and colour. This approach required immense confidence and control, as mistakes in transparent watercolour are notoriously difficult to correct. His mastery is evident in the way he could suggest complex forms – clouds, trees, rough ground – with just a few well-placed washes and strokes.

Recognition, Exhibitions, and Professional Life

Thomas Collier achieved significant recognition during his lifetime. He began exhibiting regularly in London in the 1860s. He showed works at the prestigious Royal Academy (RA), the Royal Society of British Artists (RBA, Suffolk Street), and importantly, at the galleries dedicated to watercolour painting. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours (RI) in 1870. That same year, he was also elected an Associate of the Society of Painters in Water Colours, often known as the 'Old Watercolour Society' (OWS), the most esteemed body for watercolourists in Britain.

His association with the OWS was short-lived, however. For reasons that remain somewhat unclear, but possibly related to perceived slights or disagreements over exhibition placings, he resigned his associateship just two years later in 1872. Despite this, he continued to exhibit widely and his reputation grew. His work was admired by critics and fellow artists for its strength, truthfulness, and mastery of atmospheric effect. His paintings found ready buyers among discerning collectors who appreciated his departure from more conventional Victorian tastes.

International recognition came in 1878 when he was awarded a silver medal at the Paris International Exhibition. This honour confirmed his standing not just within Britain but on a wider European stage, placing him alongside prominent French landscape painters who were also exploring naturalism and atmospheric effects, albeit often in oil paint. Artists associated with the Barbizon School in France, such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot or Charles-François Daubigny, shared a similar interest in capturing the moods of nature directly, though their techniques differed. Collier's success demonstrated the continued vitality of the British watercolour school.

The Victorian Watercolour Context

Thomas Collier worked during a period of great activity and diversity in British watercolour painting. The legacy of the early masters – Thomas Girtin (1775-1802), J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851), John Sell Cotman (1782-1842), David Cox, and Peter De Wint – provided a rich tradition upon which later artists built. By the mid-to-late Victorian era, watercolour was an immensely popular medium, practiced by professionals and amateurs alike. Styles ranged widely, from the highly detailed, brightly coloured narrative scenes or landscapes influenced by Pre-Raphaelitism, to the charming rustic idylls of artists like Helen Allingham (1848-1926) and Myles Birket Foster.

Collier's work stood somewhat apart from these dominant trends. His broad handling and emphasis on atmosphere aligned him more closely with the direct landscape sketching traditions of Cox and Constable (John Constable, 1776-1837, though primarily an oil painter, was a master of the outdoor sketch and deeply influential on naturalism). Collier's approach can be seen as a continuation and invigoration of this more robust, less finished aesthetic. He focused on capturing the essential truth of the landscape experience rather than creating a polished, idealized picture.

His contemporaries included a vast number of skilled watercolourists. While distinct from the detailed work of Foster or Allingham, his commitment to landscape found echoes in the work of others, though few matched his particular blend of breadth and sensitivity. Later artists like Alfred William Rich (1856-1921) openly acknowledged Collier's influence. Even artists associated with different movements, such as the American expatriate James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), who was working in London during Collier's later career, shared an interest in atmospheric effects and tonal harmony, albeit expressed in a very different personal style. The Newlyn School painters in Cornwall, like Stanhope Forbes (1857-1947) and Walter Langley (1852-1922), were also contemporaries focused on realistic depictions of rural and coastal life, often with a strong sense of atmosphere, though primarily in oil.

Influence and Enduring Legacy

Although Thomas Collier's career was cut short by his death at the age of 51, his influence was significant, particularly on the subsequent generation of British watercolourists who reacted against the tighter styles of the mid-Victorian period. His direct, atmospheric approach was admired and emulated by artists seeking greater freshness and expressive power in their landscape work. Alfred William Rich, a notable watercolourist and teacher, frequently cited Collier as a key influence and praised his ability to capture the 'spirit' of the landscape.

Another artist who deeply admired Collier was Hercules Brabazon Brabazon (1821-1906), an independently wealthy amateur who, late in life, gained recognition for his brilliantly coloured, highly suggestive watercolour sketches, often inspired by Turner and Collier. Brabazon collected Collier's work, recognizing in it a shared passion for colour, light, and summary execution. The painter Philip Wilson Steer (1860-1942), a leading figure in British Impressionism, also owned works by Collier and his own atmospheric landscape watercolours show a kindred spirit, particularly in their broad handling and sensitivity to light.

Today, Thomas Collier is regarded as one of the outstanding watercolourists of his generation. His works are held in major public collections in the UK, including the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Museum, Tate Britain, Manchester Art Gallery, the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, and numerous other regional galleries. His paintings continue to be sought after by collectors and admired for their technical brilliance, their evocative power, and their authentic portrayal of the British landscape. He remains a 'painter's painter', admired by those who understand the challenges and possibilities of the watercolour medium. His legacy lies in his demonstration of how watercolour could be used with boldness and freedom to convey the profound emotional impact of the natural world.

Notable Works and Collections

Unlike some artists famed for a few iconic masterpieces, Thomas Collier's reputation rests on the consistently high quality and distinctive style evident across a large body of work. His titles are often simple and descriptive, indicating the location or the conditions depicted. Examples that represent his typical subjects and style include:

Across the Common

A Sussex Common

The South Downs

Carting Peat, North Wales

Welsh Moorland

Walberswick Pier, Suffolk

On the Suffolk Coast

Richmond, Yorkshire

A Breezy Day

These titles reflect his focus on specific regions – Sussex, Wales, East Anglia, Yorkshire – and his interest in capturing weather and atmosphere. Finding specific named works consistently cited as his 'most famous' is difficult, as his strength lay in the cumulative impact of his vision applied across many canvases.

His watercolours can be studied in depth at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, which holds a significant collection. The British Museum also possesses important examples. Tate Britain includes his work within its displays of British art. Many regional museums, particularly those in areas he painted frequently, such as Brighton Museum & Art Gallery (for Sussex scenes) or galleries in Yorkshire and the North West, also hold examples. Examining these works directly reveals the subtlety of his washes, the confidence of his brushwork, and the enduring freshness of his vision, qualities that reproductions can only partially convey. His work occasionally appears at auction, where it commands respect among collectors of British watercolours.

Conclusion: An Authentic Voice in Landscape Art

Thomas Collier remains a vital figure in the history of British watercolour painting. Emerging in the mid-Victorian era, he forged a distinctive path, moving away from intricate detail towards a bolder, more atmospheric interpretation of the landscape. His deep connection to the moors, coasts, and commons of Britain, combined with his masterful handling of the watercolour medium, allowed him to create works that are both powerful representations of place and evocative expressions of mood and feeling.

Influenced by the directness of David Cox and the breadth of Peter De Wint, he developed a style characterized by confident washes, an economy of means, and an unerring ability to capture the effects of light and weather. He stood somewhat apart from the prevailing tastes of his time, yet earned significant recognition from critics, collectors, and fellow artists, including international honours. His work provided inspiration for subsequent generations of watercolourists, like Alfred William Rich and Hercules Brabazon Brabazon, who admired his freedom and truth to nature.

Though his life was relatively brief, Thomas Collier left behind a substantial body of work that continues to resonate today. His watercolours offer a compelling vision of the British landscape, rendered with a freshness, vigour, and atmospheric sensitivity that confirms his place as one of the most accomplished and authentic landscape artists of the nineteenth century. His paintings are not just records of scenery, but invitations to experience the very air, light, and spirit of the places he depicted with such skill and passion.