Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida stands as one of Spain's most celebrated artists, a pivotal figure bridging the 19th and 20th centuries. Renowned globally as the "Master of Light," his canvases radiate with the brilliant Mediterranean sun, capturing the fleeting moments of Spanish life with unparalleled vibrancy and technical skill. His work, primarily associated with Impressionism and Luminism, offers a luminous vision of his homeland, from its sun-drenched beaches to its intimate family scenes and rich cultural tapestry.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Joaquín Sorolla was born in Valencia, Spain, on February 27, 1863. His origins were humble. Tragedy struck early when, in August 1865, both his parents succumbed to a cholera epidemic. The two-year-old Joaquín and his infant sister, Concha, were orphaned and subsequently taken in and raised by their maternal aunt, Isabel Bastida, and her locksmith husband, José Piqueres.

Despite these challenging beginnings, Sorolla's artistic inclinations surfaced early. His adoptive father initially hoped he would follow the locksmith trade, but the young boy's passion for drawing was undeniable. Recognizing his talent, his uncle and the headmaster of his school encouraged his artistic pursuits. By the age of nine or ten, he was already demonstrating a remarkable ability, reportedly creating small seascapes.

Formal art education began around the age of fifteen when he enrolled at the Academy of San Carlos (Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Carlos) in Valencia. Here, he received instruction from artists such as Cayetano Capuz and Salustiano Asenjo. He proved to be a diligent and gifted student, absorbing the academic principles of drawing and composition.

A pivotal moment came at eighteen when Sorolla traveled to Madrid. The Prado Museum became his true classroom. He spent countless hours studying the Spanish Old Masters, profoundly influenced by the realism, dramatic lighting, and painterly techniques of Diego Velázquez, the expressive power of Francisco Goya, and the stark intensity of Jusepe de Ribera. This immersion in the works of his artistic forebears laid a crucial foundation for his own developing style.

After completing his compulsory military service, which he managed to shorten, Sorolla secured a grant from the Valencia Provincial Council. This enabled him, in 1885, to travel to Rome for further study at the Spanish Academy. Rome offered exposure to classical art and the Italian masters, but Sorolla also connected with other Spanish artists there, including Francisco Pradilla Ortiz, who became a significant mentor during this period.

Development of a Unique Style

Sorolla's time in Italy, followed by a crucial visit to Paris in 1885, broadened his artistic horizons significantly. In Paris, he encountered contemporary art movements, particularly Naturalism as practiced by artists like Jules Bastien-Lepage, and the burgeoning Impressionist movement. While not strictly adhering to French Impressionist dogma, the emphasis on capturing light and momentary effects resonated deeply with him. Artists like the German Adolph Menzel, known for his realistic depictions and light studies, also caught his attention.

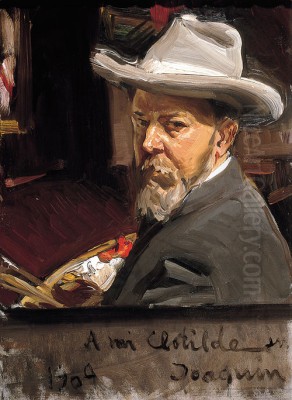

Upon returning to Spain, Sorolla initially settled in Assisi before moving back to Valencia and eventually establishing himself in Madrid in 1889. That same year, he married Clotilde García del Castillo, the daughter of the photographer Antonio García Peris, in whose studio Sorolla had previously worked. Clotilde would become his lifelong muse, companion, and the subject of many tender portraits, alongside their three children: María, Joaquín Jr., and Elena.

During the late 1880s and 1890s, Sorolla gained recognition through participation in national and international exhibitions. His early major works often tackled historical or social realist themes, reflecting the academic expectations of the time. A key example is Another Marguerite (Otra Margarita, 1892), depicting a woman arrested for infanticide. This powerful piece earned him a gold medal at the National Exhibition in Madrid and first prize at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, launching his international career.

Another significant work from this period, Sad Inheritance (Triste herencia, 1899), portrayed crippled children bathing in the sea at Valencia under the watchful eye of a monk. This poignant painting, showcasing his growing mastery of light on water and figures, won him the Grand Prix and a medal of honor at the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1900, and the medal of honor at the National Exhibition in Madrid in 1901. These successes cemented his reputation but also marked a turning point.

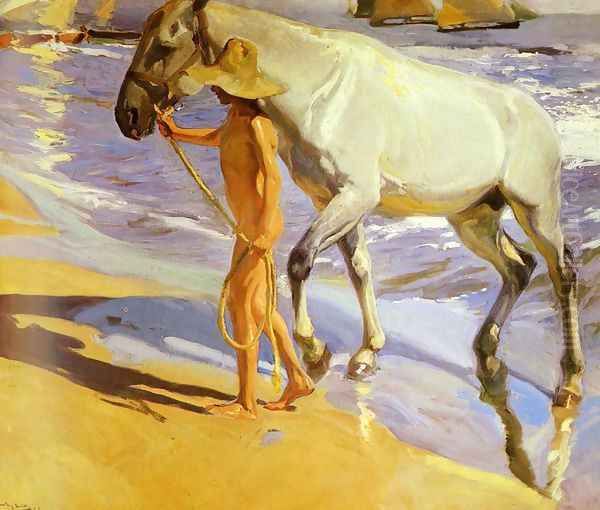

Increasingly, Sorolla moved away from somber social commentary towards celebrating the beauty of everyday life, particularly the sunlit world of the Valencian coast. He embraced plein air painting, working outdoors directly from nature to capture the immediate sensations of light and atmosphere. This shift defined his mature style, characterized by brilliant palettes, loose and energetic brushwork, and an extraordinary ability to render the dazzling effects of sunlight on figures, sand, and sea.

The Painter of Light and Spanish Life

Sorolla's name became synonymous with the depiction of light. His unique brand of Impressionism, often termed "Luminism" (Luminismo) in the Spanish context, focused on the intense, often blinding, sunlight of his native Mediterranean coast. He wasn't merely painting scenes bathed in light; he was painting the light itself – how it reflected, refracted, and defined form and color. His technique involved rapid, confident brushstrokes, often leaving areas of the canvas visible, contributing to the sense of immediacy and vibrancy.

His subject matter shifted decisively towards the optimistic and the beautiful. The beaches of Valencia, particularly Malvarrosa beach, became his open-air studio. He painted countless scenes of children splashing in the waves, fishermen hauling in their nets or mending sails, and elegantly dressed women strolling along the shore under parasols. These works exude a sense of joy, freedom, and the simple pleasures of life under the Spanish sun.

Iconic paintings from this period include Sewing the Sail (Cosiendo la vela, 1896), a luminous depiction of sailmakers working in a sun-dappled courtyard, showcasing his skill with white fabrics and complex light patterns. Children on the Beach (Niños en la playa, 1910) and After the Bath (Después del baño, Valencia, 1909) capture the uninhibited energy of youth and the glistening effect of water on sun-kissed skin with remarkable realism and fluidity.

His masterpiece, Walk on the Beach (Paseo a orillas del mar, 1909), portrays his wife Clotilde and eldest daughter María elegantly dressed, walking along the Valencian shore, their white dresses billowing in the sea breeze against a backdrop of dazzling blue sea and sky. It is a quintessential Sorolla image – sophisticated, bathed in brilliant light, and capturing a fleeting, intimate moment with effortless grace.

Sorolla was also a highly sought-after portraitist. He painted prominent figures, including Spanish royalty like King Alfonso XIII, intellectuals, fellow artists, and his own family members. His portraits, while often formal commissions, retained the characteristic freshness, vibrant light, and psychological insight of his other work. He masterfully captured the personality of his sitters, often placing them in natural, light-filled settings.

National and International Recognition

By the early 20th century, Sorolla was arguably Spain's most famous living artist, enjoying immense success both at home and abroad. He exhibited regularly and successfully in Paris, Berlin, London, and major cities across the United States. His style, while rooted in Spanish tradition and landscape, had a universal appeal.

His solo exhibition at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris in 1906 was a triumph, showcasing nearly 500 works and solidifying his reputation in the European art capital. This was followed by a highly successful show at the Grafton Galleries in London in 1908. However, his greatest international acclaim arguably came from the United States.

In 1909, Sorolla held a monumental exhibition at the Hispanic Society of America in New York City, organized by its founder, the Hispanophile millionaire Archer Milton Huntington. The show was an unprecedented sensation, attracting nearly 160,000 visitors in one month. Sorolla sold close to 200 paintings, and the exhibition subsequently toured to Buffalo and Boston, meeting with similar enthusiasm. This tour established him as a major artistic figure in America.

During his time in the US, he received numerous portrait commissions, including one from President William Howard Taft, whom he painted at the White House in 1909. His success was often compared to that of the expatriate American painter John Singer Sargent, another master portraitist known for his fluid brushwork and elegant depictions of high society. While both artists excelled at capturing light and personality, Sorolla's work remained deeply rooted in his Spanish identity, often featuring more vibrant color and a focus on outdoor scenes compared to Sargent's more typically interior settings. Other contemporary portraitists like the Italian Giovanni Boldini also worked in a similarly bravura style.

Sorolla's relationship with Archer Huntington proved particularly fruitful. Huntington became a major patron, acquiring numerous works for the Hispanic Society's collection and commissioning Sorolla's most ambitious project. Sorolla's international fame placed him alongside other prominent Spanish artists of the era, such as the Basque painter Ignacio Zuloaga, whose darker, more dramatic vision of Spain offered a stark contrast to Sorolla's sunlit world. He was also contemporary with Valencian artists like Ignacio Pinazo Camarlench and Francisco Domingo Marqués, whose work shared some affinities with his own approach to light and local themes.

The Vision of Spain

The culmination of Sorolla's relationship with Archer Huntington was the monumental commission received in 1911: a series of large-scale panels depicting the regions of Spain, intended to decorate the library of the Hispanic Society of America in New York. Titled Visión de España (Vision of Spain), this vast project would consume much of the last decade of Sorolla's working life.

To fulfill this commission, Sorolla embarked on extensive travels throughout Spain between 1912 and 1919. He sought to capture the distinct character, costumes, traditions, and landscapes of regions from Andalusia and Aragon to Galicia, the Basque Country, Catalonia, and his native Valencia. He painted enormous canvases en plein air, often under challenging conditions, striving for authenticity and vibrant realism on an epic scale.

The fourteen magnificent panels, some measuring up to 14 feet high, depict scenes of festivals, harvests, fishing, and local customs. They represent a panoramic celebration of Spanish regional identity, rendered with Sorolla's characteristic brilliance of light and color, albeit sometimes with a more decorative and ethnographic focus dictated by the commission. Notable panels include Ayamonte: Tuna Fishing, Seville: The Bullfighters, and Castilla: The Bread Festival.

This immense undertaking took a heavy toll on the artist's health and energy. He felt the weight of the responsibility and the physical demands of working on such large canvases outdoors. Despite the challenges, he completed the final panel in 1919. Although he never saw the panels installed in New York (they were put in place after his death), the Vision of Spain remains a unique and powerful testament to his love for his country and his extraordinary artistic stamina.

Later Years, Legacy, and Influence

After completing the Hispanic Society murals, Sorolla returned to Madrid, exhausted but fulfilled. He continued to paint, finding solace and inspiration in the gardens of his Madrid home, which he had designed himself. These later garden paintings, often featuring his family members, are more intimate and contemplative, showcasing a continued fascination with the interplay of light, shadow, and color on foliage and flowers.

Tragically, Sorolla's prolific career was cut short. In June 1920, while painting a portrait in the garden of his Madrid home, he suffered a stroke that left him paralyzed and unable to paint. He spent the last three years of his life cared for by his family, passing away in Cercedilla, near Madrid, on August 10, 1923.

Sorolla's legacy was carefully preserved by his widow, Clotilde García del Castillo. Following his wishes, she bequeathed their Madrid home and its contents, including a vast collection of his paintings, drawings, and personal effects, to the Spanish state. In 1932, the house opened as the Museo Sorolla, offering an intimate glimpse into the artist's life and work, preserved much as he left it. It remains one of Madrid's most beloved museums.

In the decades immediately following his death, Sorolla's reputation experienced a relative decline, overshadowed by the rise of avant-garde movements like Cubism, led by his younger compatriot Pablo Picasso, and Surrealism. Sorolla's optimistic realism and focus on traditional Spanish themes seemed less relevant to critics championing radical artistic innovation. Artists like Juan Gris were exploring entirely different pictorial languages.

However, beginning in the late 20th century and continuing into the 21st, there has been a significant resurgence of interest in Sorolla's work. Major international exhibitions have reintroduced his art to global audiences, highlighting his technical brilliance, his unique handling of light, and the enduring appeal of his subject matter. He is now firmly recognized as a major figure in Spanish and European art history, a master whose influence extended to subsequent generations of Spanish painters, particularly in Valencia, such as José Mongrell Torrent or Julio Vila y Prades, who continued the Luminist tradition.

Sorolla's Enduring Appeal

What accounts for Joaquín Sorolla's lasting popularity? Firstly, his sheer technical virtuosity is undeniable. His ability to capture the dazzling effects of light with seemingly effortless brushwork remains astonishing. His compositions are dynamic, his colors vibrant, and his drawing skills impeccable, all serving his vision of capturing fleeting reality.

Secondly, his subject matter resonates with viewers. His paintings often celebrate life, family, and the beauty of the natural world. The sunlit beaches, the joyful children, the dignity of labor, and the intimate family portraits evoke a sense of warmth, nostalgia, and optimism that contrasts with the often darker or more cerebral concerns of modern art. His work offers an accessible and uplifting vision.

Thirdly, Sorolla's art is deeply connected to Spanish identity. He painted Spain with love and understanding, capturing its light, its people, and its traditions without resorting to stereotype. His Vision of Spain murals, in particular, stand as a monumental tribute to the cultural diversity of his homeland.

Today, Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida is celebrated not just as the "Painter of Light," but as a master storyteller in paint, an artist who captured the soul of Spain bathed in the Mediterranean sun. His works continue to enchant audiences worldwide, securing his place alongside Velázquez and Goya in the pantheon of great Spanish artists. His legacy lives on through the Museo Sorolla and the countless canvases that radiate his unique, luminous vision.