Johann Amandus Winck stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the annals of German art history. Active during the latter half of the 18th century and the early 19th century, Winck dedicated his artistic endeavors primarily to the genre of still life, achieving a remarkable degree of finesse and recognition in his time. His meticulously rendered compositions of fruits, flowers, and game not only reflect the enduring legacy of the Dutch Golden Age masters but also embody the specific cultural and artistic currents of his native Bavaria. This exploration delves into the life, work, artistic milieu, and legacy of a painter who captured the ephemeral beauty of the natural world with enduring skill.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis in Bavaria

Johann Amadus Winck was born in 1754 (some sources suggest 1748, though 1754 appears more consistently in detailed accounts) in the picturesque town of Eichstätt, nestled in the heart of Bavaria, Germany. This region, with its rich natural landscapes and established traditions of craftsmanship, likely provided early inspiration for the budding artist. From a young age, Winck reportedly displayed a keen interest in both botany and the visual arts, a combination of passions that would define his later specialization.

His artistic inclinations were undoubtedly nurtured by his family environment. Winck hailed from a lineage of artists; his father, Johann Chrysostomus Winck (1725-1797), was a court painter in Eichstätt. Furthermore, his uncle, Thomas Christian Winck (1738-1797), also pursued a career as a court painter. This familial immersion in the arts would have provided Johann Amandus with invaluable early exposure to techniques, materials, and the professional life of an artist. It is highly probable that his initial training commenced under the tutelage of his father and uncle, learning the foundational skills of drawing and painting within a workshop setting.

To further hone his craft, Winck sought formal education beyond his local sphere. He is documented as having studied at the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts in Antwerp. During the 18th century, Antwerp, though past its zenith as the dominant artistic center it had been in Rubens' time, still maintained a strong tradition in painting, particularly in genres like still life, which had deep roots in Flemish art. This period of study would have exposed him to a wider range of artistic influences and technical approaches. Some accounts suggest he may also have received instruction from Peter Jacob Horemans (1700-1776), a court painter in Munich, which would have further connected him to the Bavarian court art scene.

The Enduring Influence of Dutch Masters

A pivotal aspect of Johann Amandus Winck's artistic development was his profound admiration for and assimilation of the Dutch still-life tradition of the 17th and early 18th centuries. Artists like Jan van Huysum (1682-1749) were particularly revered. Van Huysum, known for his opulent and exquisitely detailed flower pieces and fruit still lifes, set a standard of technical brilliance and compositional elegance that resonated deeply with later generations of painters, including Winck. Though Van Huysum belonged to an earlier generation, his works were widely collected and emulated, serving as models of perfection.

Winck's aspiration to become a still-life master was significantly shaped by such luminaries. He would have studied their handling of light to create luminous, almost tangible textures on fruits and petals, their skill in arranging complex compositions that appeared both natural and artfully designed, and their meticulous attention to detail, right down to the dewdrops on a leaf or the delicate wings of an insect. The Dutch masters excelled in capturing the varying textures of objects – the soft bloom on a grape, the reflective sheen of a silver platter, the transparency of a glass. These were qualities Winck strove to emulate in his own work.

Other artists from this rich tradition, such as Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750), a celebrated female painter of flower still lifes, or Willem Kalf (1619-1693), known for his sumptuous pronkstilleven (ostentatious still lifes), contributed to the vocabulary of the genre that Winck inherited. While German still life had its own pioneers, like Georg Flegel (1566-1638) much earlier, or later figures like Abraham Mignon (1640-1679) who bridged German and Dutch styles, the overwhelming prestige of the Dutch school was undeniable in the 18th century.

Winck's Artistic Style: Precision and "Früchte- und Blumenstücke"

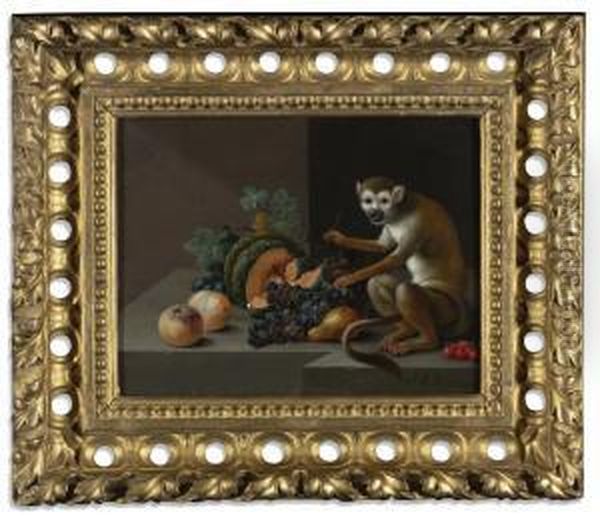

Johann Amandus Winck carved a niche for himself with his "Früchte- und Blumenstücke," or fruit and flower pieces. These compositions were characterized by their meticulous detail, vibrant yet controlled palette, and sophisticated arrangements. He often combined Mediterranean fruits, such as lemons and grapes, which signified a certain exoticism and luxury, with local Bavarian produce and flora. This blend created a sense of abundance and celebrated the diversity of the natural world.

A hallmark of Winck's style was his exceptional technical skill. He rendered textures with remarkable fidelity, making viewers feel they could almost touch the velvety skin of a peach or the cool surface of a porcelain vase. His depiction of insects – butterflies, beetles, or flies – alighting on fruits or flowers was not merely decorative but added a layer of naturalism and often carried symbolic meaning, alluding to the transience of life and beauty, a common theme in still-life painting (vanitas).

Winck was also adept at employing trompe-l'oeil techniques, an artistic device meaning "to deceive the eye." Elements in his paintings could appear so realistic that they seemed to project out of the picture plane, blurring the line between the painted world and the viewer's reality. This skill demonstrated his mastery of perspective and his understanding of how light and shadow model form. His compositions were typically carefully balanced, often with a diagonal emphasis or a pyramidal structure, guiding the viewer's eye through the array of objects. The interplay of light was crucial, highlighting key elements and creating a sense of depth and volume.

Notable Works and Court Patronage

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné of Winck's oeuvre might be elusive, several works and types of commissions illustrate his artistic output. One example cited for its detailed execution is a painting described as "A statue, a dead rabbit, poultry and a piglet gnawing," showcasing his ability to render diverse textures and subjects, including game, which was another popular subgenre of still life. Titles like "Still Life with Grapes and Lemon" ("Still Life with Trauben und Zitrone") are indicative of his typical subject matter.

His talent did not go unnoticed by the Bavarian aristocracy. In 1777, Winck was commissioned by the Bavarian court to create four designs for Gobelins tapestries. Tapestries were luxury items of the highest order, and designing for such a prestigious medium was a significant honor, underscoring his standing as a respected artist. He is also documented as having collaborated with his uncle, Thomas Christian Winck, on mural projects. Murals and large-scale decorative paintings were essential components of palatial and ecclesiastical interiors during this period, demanding versatility and skill in handling complex compositions on a grand scale.

Two particularly famous still-life paintings by Winck were reportedly commissioned by the Bavarian court in the early 19th century. These works were later held in the collection of the von Zimmermann family in Schweinsteig, attesting to their quality and the esteem in which they were held. Such courtly patronage was vital for artists of Winck's era, providing financial stability and enhancing their reputation.

The Artistic and Social Milieu of Winck's Time

Johann Amandus Winck's career spanned a period of significant artistic and social change in Europe. Artistically, the late 18th century saw the Rococo style, with its emphasis on lightness, elegance, and asymmetry, gradually giving way to the more austere and ordered principles of Neoclassicism, inspired by the art of ancient Greece and Rome. Concurrently, the seeds of Romanticism, with its focus on emotion, individualism, and the sublime power of nature, were beginning to sprout. While still life as a genre often maintained a degree of stylistic continuity, these broader shifts undoubtedly influenced the tastes of patrons and the overall artistic climate.

Germany, during Winck's lifetime, was a complex patchwork of states within the Holy Roman Empire (until its dissolution in 1806). Bavaria, under its Electors and later Kings, was a prominent cultural center. The Enlightenment, or Aufklärung in German, was also a powerful intellectual force, promoting reason, scientific inquiry, and a new appreciation for the natural world. This burgeoning interest in botany and natural history found a parallel in the detailed and accurate depiction of flora and fauna in still-life painting. Winck's meticulous rendering of plants and insects can be seen as aligning with this scientific spirit of observation.

The Napoleonic Wars (c. 1803-1815) profoundly reshaped the political map of Europe, including the German states. Bavaria, for a time, allied with Napoleonic France and was elevated to a Kingdom in 1806. These turbulent times brought both upheaval and new opportunities. Despite the political shifts, the demand for art, particularly for courtly and private decoration, continued. The art market was maturing, and artists like Winck could find patronage not only from the highest echelons of the nobility but also from a growing bourgeois class.

Contemporaries and the Broader Artistic Landscape

Winck was part of a vibrant artistic ecosystem. In the realm of still life, while he looked back to Dutch masters like Jan van Huysum and Rachel Ruysch, he also had contemporaries. Peter Faes (1750-1814), a Flemish painter specializing in flower pieces, was active during the same period and worked in a similar vein, continuing the rich tradition of Flemish floral painting. Within Germany, artists like Justus Juncker (1703-1767), though slightly earlier, had also contributed to the German still-life tradition.

The influence of court painters was significant. Winck's own family background attests to this, and his potential tutelage under Peter Jacob Horemans in Munich would have further embedded him in this system. Court painters were responsible for a wide range of artistic production, from portraits and historical scenes to decorative schemes and, indeed, still lifes, which were prized for their beauty and suitability for adorning dining rooms and private chambers.

Looking beyond still life, the broader German-speaking art world included figures who would rise to greater international fame in the subsequent Romantic era, such as Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) or Philipp Otto Runge (1777-1810). While their thematic concerns and styles differed greatly from Winck's, they were part of the same generational cohort experiencing the cultural shifts of the time. In Austria, Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller (1793-1865), though of a slightly later generation and known more for Biedermeier portraits and landscapes, represents the continuation of meticulous realism in a different context. There is no evidence of direct collaboration or competition between Winck and Waldmüller, but their works might appear in similar historical catalogues or collections, reflecting the art of the broader period. Similarly, the Swiss landscape painter Robert Zünd (1827-1909) belongs to a much later period but might be encountered when studying the provenance or cataloguing of 19th-century German-area art.

The great Baroque master Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) was, of course, from a much earlier era, but his legacy in Antwerp and Flanders was immense, shaping the artistic DNA of the region where Winck later studied. While not a direct influence on Winck's still lifes in the same way as Van Huysum, Rubens' dynamic compositions and rich use of color set a high bar for artistic excellence in the Low Countries.

Anecdotes and Professional Standing

Specific personal anecdotes about Johann Amandus Winck are not extensively documented, which is common for many artists of his era who did not achieve the superstar status of a Rubens or Rembrandt. However, the available information paints a picture of a dedicated and successful professional. His early and sustained interest in botany, coupled with his artistic talent, suggests a focused and passionate individual.

His decision to study in Antwerp indicates ambition and a desire to learn from the best traditions. The commissions from the Bavarian court, including the Gobelins tapestry designs and mural work (possibly with his uncle), are clear indicators of his high professional standing and the trust placed in his abilities by discerning patrons. Such commissions were not awarded lightly and speak to his established reputation.

The fact that his works appeared in significant collections, like that of the von Zimmermann family, and continue to surface in the art market, sometimes fetching considerable prices (a "Fruchtestillleben" was noted to have an auction estimate of €6,000-€10,000 in one instance), demonstrates the enduring appeal and recognized quality of his paintings. He was considered one of the representative figures of German still-life painting in the early 19th century.

Legacy and Conclusion

Johann Amandus Winck passed away in Munich in 1817. He left behind a body of work that exemplifies the enduring allure of still-life painting. His art skillfully blended the meticulous realism and compositional elegance of the Dutch tradition with a sensibility that was distinctly his own, reflecting the tastes and cultural environment of late 18th and early 19th-century Bavaria.

While perhaps not a radical innovator who dramatically altered the course of art history, Winck was a master of his chosen genre. He upheld a tradition of excellence, demonstrating superb technical command and a sensitive eye for the beauty of the natural world. His "Früchte- und Blumenstücke" are more than mere depictions of objects; they are carefully constructed meditations on texture, light, color, and form, often imbued with subtle symbolism.

In the grand narrative of art history, specialists like Johann Amandus Winck play a crucial role. They represent the depth and breadth of artistic practice within specific regions and genres, enriching our understanding of the cultural fabric of their time. His paintings offer a window into the aesthetic preferences of his era and stand as testaments to the timeless appeal of skillfully rendered depictions of nature's bounty. As an art historian, it is important to recognize and appreciate the contributions of artists like Winck, who, within their specific domain, achieved a high level of mastery and left a legacy of beautiful and meticulously crafted works for posterity. His paintings continue to be admired in collections and at auction, a quiet testament to a dedicated artistic life.