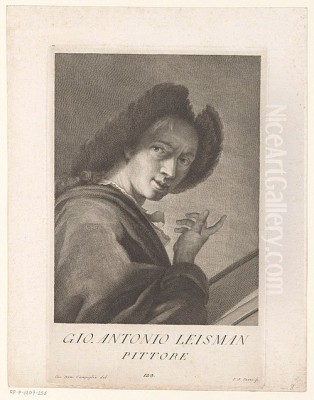

Johann Anton Eismann stands as a notable, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of 17th-century European art. An Austrian by birth, he carved out a significant career primarily in Italy, becoming an integral part of the Venetian school of painting. His oeuvre, characterized by dramatic landscapes, tumultuous battle scenes, and evocative seascapes, reflects both the artistic currents of his time and a distinct personal vision. Though perhaps not as universally recognized today as some of his contemporaries, Eismann's contributions to the development of landscape and genre painting, particularly the capriccio, were substantial, influencing other artists and leaving behind a body of work that continues to intrigue art historians and enthusiasts alike.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis

Born in Salzburg around 1604, Johann Anton Eismann's early artistic training remains somewhat obscure. Salzburg, at that time, was an ecclesiastical principality with a burgeoning Baroque culture, but it was Italy, the artistic crucible of Europe, that would ultimately shape his career. Like many artists from Northern Europe, Eismann was drawn south by the allure of classical antiquity, the masterpieces of the Renaissance, and the dynamic contemporary art scene.

He is documented as having moved to Venice, a city that, even in the 17th century, retained its allure as a major artistic center. It was here, amidst the canals and palazzi, that Eismann truly honed his craft. The provided information suggests he was largely self-taught or learned through the diligent practice of copying and studying the works of established masters available to him in Venice. This method of learning was common, allowing artists to absorb techniques, compositional strategies, and thematic repertoires. His arrival in Venice is generally placed around the 1650s or early 1660s, marking the beginning of his most productive period.

The Venetian Artistic Milieu

Venice in the latter half of the 17th century was a city of contrasts. While its political and maritime power was in gradual decline, its cultural life, particularly in painting, music, and theatre, remained vibrant. The grand tradition of Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese had given way to new artistic concerns. Landscape painting, which had previously been a backdrop for religious or mythological scenes, was emerging as an independent genre. This was partly due to the influence of Northern European artists working in Italy, such as Paul Bril and later Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin in Rome, whose idealized landscapes found an appreciative audience.

In Venice itself, a taste for vedute (view paintings) and capricci (fantastical architectural or landscape compositions) was developing. Artists like Joseph Heintz the Younger, a German painter active in Venice, were already exploring festive scenes and allegories set within recognizable Venetian locales. It was into this evolving artistic landscape that Eismann inserted himself, bringing his Northern sensibilities to bear on Italianate themes.

Key Themes and Stylistic Traits

Eismann's artistic output primarily revolved around landscapes, seascapes (often featuring bustling harbors), and battle scenes. His style is often described as being influenced by the Italian Baroque painter Salvator Rosa. Rosa, active in Naples, Rome, and Florence, was renowned for his wild, untamed landscapes, often populated by bandits, soldiers, or hermits, and imbued with a sense of drama and the sublime. Eismann appears to have absorbed Rosa's penchant for rugged scenery, dramatic lighting, and dynamic compositions.

His landscapes frequently incorporate classical ruins, a common motif in the capriccio genre, blending real and imagined architectural elements to create picturesque and evocative scenes. These works often feature a lively animation, with numerous small figures engaged in various activities, adding narrative interest and a sense of scale. The depiction of "wild nature" combined with these Roman ruins became a hallmark of his landscape work, echoing Rosa's romanticism but often with a slightly more ordered, Venetian sensibility.

Eismann was particularly praised for his ability to capture atmospheric effects, especially in his skies. This skill in rendering light and air contributed significantly to the mood of his paintings, whether it was the turbulent sky over a battlefield or the luminous haze of a Mediterranean port. This focus on atmosphere was a quality that even Salvator Rosa reportedly admired in Eismann's work, suggesting that Eismann was an innovator in this regard, perhaps even predating Luca Carlevaris in certain "capricci" elements.

Major Works and Their Characteristics

Several of Johann Anton Eismann's works are preserved, notably in the National Gallery Prague, offering insight into his thematic concerns and artistic style.

_Bitva_ (Battle): This painting exemplifies his skill in depicting the chaos and dynamism of warfare. Battle scenes were a popular genre in the Baroque period, allowing artists to showcase their ability in rendering complex figure compositions, dramatic action, and emotional intensity. Eismann's battle paintings are typically filled with charging cavalry, clashing soldiers, and the smoke and fury of combat, often set against a dramatic landscape backdrop. He would have been aware of the work of specialists in this genre, such as Jacques Courtois, known as "Il Borgognone," who was highly influential in popularizing large-scale battle paintings.

_Capriccio suzu kříšťalu Santa Maria della Salute v Benátkách_ (Fantasy Landscape with Santa Maria della Salute in Venice): This title suggests a capriccio, a work that combines real architectural landmarks with imaginary settings or perspectives. The iconic dome of Santa Maria della Salute, a masterpiece by Baldassare Longhena, would have been a familiar sight to Eismann. By placing it within a "fantasy landscape," he engaged in the playful reinterpretation of reality that characterized the capriccio genre. This type of painting appealed to the sophisticated tastes of collectors who appreciated wit and invention.

_Ein Meerhafen_ (A Seaport): Seaport scenes were another of Eismann's specialties. These paintings typically depict bustling harbors with ships, merchants, and various figures going about their business, often set against a backdrop of classical or contemporary architecture. These works allowed Eismann to demonstrate his skill in rendering maritime details, architectural perspectives, and the lively interplay of figures. They often evoke a sense of exoticism and the vibrant commercial life of port cities like Venice.

_Belagerung Besteged City_ (Siege of a City) and _Oblédmanshipě města_ (City Defense/Siege): These titles, both located in the National Gallery Prague, further underscore his interest in military themes. Siege paintings offered a different kind of drama than open-field battles, focusing on fortifications, artillery, and the prolonged struggle between attackers and defenders. Such works often carried symbolic weight, reflecting contemporary anxieties about warfare and the vulnerability of cities.

The presence of several of his works in the National Gallery Prague, some possibly originating from an 1814 inventory and the Würbs catalogue, indicates that his paintings were collected and valued. Other collections, such as the Dresden Gallery, also hold works attributed to him, attesting to his reputation beyond Venice.

Influence and Connections with Contemporaries

Johann Anton Eismann did not operate in an artistic vacuum. His development was shaped by exposure to other artists, and his own work, in turn, had an impact on his contemporaries and successors.

The most frequently cited influence on Eismann is Salvator Rosa (1615-1673). Rosa's dramatic and romantic landscapes, often featuring wild, untamed nature, bandits, and stormy skies, clearly resonated with Eismann. Eismann adopted Rosa's penchant for rugged scenery and dramatic compositions, though perhaps with a slightly less overtly philosophical or melancholic tone.

There is also speculation about the influence of Pieter Mulier the Younger, known as "Cavalier Tempesta" (c. 1637-1701). Mulier, a Dutch painter who spent much of his career in Italy (Rome, Genoa, and later Milan and Venice), was renowned for his stormy seascapes and dramatic landscapes. If Eismann spent time in Rome, as some sources suggest, or encountered Mulier's work in Venice, it is plausible that Mulier's dynamic and atmospheric style could have impacted him. However, concrete evidence for a youthful Roman visit by Eismann or direct tutelage under Mulier remains elusive.

Eismann's relationship with Luca Carlevaris (1663-1730) is particularly interesting. Carlevaris, an Udinese painter who settled in Venice, is often considered a foundational figure in Venetian veduta painting, a precursor to Canaletto. Some art historical accounts suggest that Carlevaris, in his earlier phase, was influenced by Eismann's landscape and capriccio style before developing his more topographically accurate and detailed views of Venice. If Eismann's "capricci" indeed predated or ran concurrently with Carlevaris's early explorations, it positions Eismann as an important innovator in this Venetian specialty.

Eismann's work also appears to have influenced Marco Ricci (1676-1730). Ricci, nephew of the history painter Sebastiano Ricci, became a prominent landscape painter, known for his romantic landscapes, capricci with ruins, and stormy scenes. Marco Ricci, like Eismann, was influenced by Salvator Rosa, but also by other Northern landscape painters active in Italy. It is quite conceivable that Eismann's established presence and specific stylistic traits contributed to the artistic environment that shaped Ricci's own landscape painting.

The broader context of landscape painting in Italy at the time included figures like Claude Lorrain (1600-1682) and Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665) in Rome, who established the classical, idealized landscape. While Eismann's style was generally more dramatic and less serene than Lorrain's, the overall elevation of landscape as a genre provided a fertile ground for his work. Another figure in Italian landscape, though with a very different, more agitated and visionary style, was Alessandro Magnasco, known as "Lissandrino" (1667-1749), whose work often featured elongated, nervous figures in dramatic settings. While their styles differed, they both contributed to the diversity of landscape and genre painting in Italy.

The Dutch Italianates, such as Jan Both (c. 1610/18–1652) or Nicolaes Berchem (1620–1683), who brought a Northern European sensibility to Italian light and scenery, also formed part of the wider artistic exchange that Eismann participated in, albeit as an Austrian working within the Italian tradition. Even earlier figures like Adam Elsheimer (1578-1610), a German painter who worked in Rome and influenced many with his small, intensely lit landscapes, contributed to the rich tradition Eismann inherited.

The Art of Battle Painting

Eismann's dedication to battle scenes places him within a specific and popular Baroque genre. The 17th century was an age of frequent warfare, and depictions of battles, sieges, and skirmishes found a ready market. These paintings were not merely documentary; they often served to glorify military prowess, commemorate victories, or explore the human drama of conflict.

Artists specializing in this genre, like the aforementioned Jacques Courtois (Il Borgognone), set a high standard for dynamic composition, anatomical accuracy, and the depiction of equine energy. Eismann's battle pieces, with their swirling masses of figures, dramatic lighting, and often expansive landscape settings, fit well within this tradition. He would have aimed to capture the terribilità – the awesome and terrible aspect – of war, appealing to patrons who appreciated both the technical skill involved and the visceral impact of the subject matter. His Austrian origins might also have given him a particular perspective on military themes, given the Habsburg Empire's frequent involvement in conflicts during this period.

The Capriccio and Imaginary Landscapes

The capriccio, as a genre, offered artists like Eismann considerable freedom. It involved the imaginative combination of real and fantastical architectural elements, often classical ruins, set within picturesque landscapes. These were not meant to be accurate topographical views but rather evocative compositions that stimulated the viewer's imagination and appreciation for artistic invention.

Eismann's capricci often featured Roman ruins, reflecting the ongoing fascination with classical antiquity. These ruins were not just picturesque elements; they could also evoke themes of transience, the passage of time, and the grandeur of past civilizations. By populating these scenes with contemporary figures, Eismann created a dialogue between past and present. His skill in rendering atmospheric effects would have been particularly valuable in this genre, allowing him to create moods ranging from the idyllic to the melancholic. The development of the capriccio in Venice, to which Eismann contributed, paved the way for later masters of the form, including Canaletto and Francesco Guardi, who often produced capricci alongside their more famous vedute.

Later Career, Legacy, and Art Historical Standing

Johann Anton Eismann is recorded as having returned to Venice in 1663 after a period that may have included time in Rome, though details of his movements can be sparse. He continued to work in Venice and Verona, and it is noted that he was a member of the Venetian painters' guild (Fraglia dei Pittori) at some point during his active years, indicating his professional standing within the city's artistic community. He died in Venice in 1698.

Despite his productivity and the apparent esteem he enjoyed during his lifetime, Eismann's name has not always maintained the prominence of some of his Venetian contemporaries. This can be attributed to several factors. Attribution issues have sometimes clouded his oeuvre; the provided information mentions a possible confusion with a certain Luca Giambattista Zucchi, which could lead to misattributions of works. Furthermore, artists who moved between centers or whose styles did not fit neatly into dominant narratives sometimes faced a degree of posthumous neglect.

However, art historical scholarship has increasingly recognized the contributions of artists like Eismann who operated within specific genres and influenced local schools. His role as an early exponent of certain types of landscape and capriccio painting in Venice is significant. His ability to synthesize influences, particularly that of Salvator Rosa, with his own vision resulted in a distinctive body of work. The presence of his paintings in important museum collections and their appearance at auctions attest to a continuing interest in his art.

Art historians evaluate Eismann as an important figure in the development of Venetian landscape painting in the latter 17th century. He is seen as a bridge figure, absorbing international influences (like the dramatic naturalism of Rosa) and adapting them to the Venetian context, thereby contributing to the city's rich artistic output in this genre. His influence on younger artists like Luca Carlevaris and Marco Ricci further solidifies his place in the lineage of Venetian landscape and capriccio painting.

Challenges in Eismann Scholarship

Reconstructing the full career and impact of Johann Anton Eismann presents certain challenges for art historians. As with many artists of his era who were not extensively documented by contemporary biographers like Baldinucci or Soprani, details of his training, travels, and patronage can be fragmentary.

The issue of attributions is a common one for artists of this period. Stylistic similarities, workshop practices, and the passage of time can lead to confusion. The mention of a possible mix-up with Luca Giambattista Zucchi highlights this. Careful connoisseurship, technical analysis, and archival research are often needed to clarify an artist's catalogue raisonné.

The debate about a youthful visit to Rome and the potential influence of Pieter Mulier is another area where definitive evidence is lacking. While plausible, such connections require more than stylistic affinity to be firmly established. Despite these challenges, the core body of work attributed to Eismann provides a clear sense of his artistic personality and his contribution to the genres he favored.

Conclusion: An Enduring Contribution

Johann Anton Eismann emerges from the historical record as a skilled and imaginative painter who made a significant mark on the Venetian art scene of the late 17th century. His dramatic landscapes, energetic battle scenes, and evocative harbor views, often infused with the spirit of the capriccio, demonstrate a mastery of composition, atmospheric effect, and lively figural depiction.

Influenced by major figures like Salvator Rosa, Eismann forged his own path, contributing to the evolution of landscape painting in Venice and influencing subsequent generations of artists, including Luca Carlevaris and Marco Ricci. While perhaps not a household name on the scale of a Canaletto or Guardi, who would later bring Venetian view painting to its zenith, Eismann played a crucial role in laying the groundwork for these later developments. His works, found in collections such as the National Gallery Prague and the Dresden Gallery, continue to be appreciated for their dynamism, their imaginative power, and their embodiment of the rich artistic currents of Baroque Italy. As an Austrian who found his artistic voice in the vibrant milieu of Venice, Johann Anton Eismann remains a compelling figure in the history of European art.